Hyperfunction

In mathematics, hyperfunctions are generalizations of functions, as a 'jump' from one holomorphic function to another at a boundary, and can be thought of informally as distributions of infinite order. Hyperfunctions were introduced by Mikio Sato in 1958, building upon earlier work by Grothendieck and others. In Japan, they are usually called the Sato's hyperfunctions.

Formulation

A hyperfunction on the real line can be conceived of as the 'difference' between one holomorphic function defined on the upper half-plane and another on the lower half-plane. That is, a hyperfunction is specified by a pair (f, g), where f is a holomorphic function on the upper half-plane and g is a holomorphic function on the lower half-plane.

Informally, the hyperfunction is what the difference f − g would be at the real line itself. This difference is not affected by adding the same holomorphic function to both f and g, so if h is a holomorphic function on the whole complex plane, the hyperfunctions (f, g) and (f + h, g + h) are defined to be equivalent.

Definition in one dimension

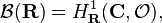

The motivation can be concretely implemented using ideas from sheaf cohomology. Let  be the sheaf of holomorphic functions on C. Define the hyperfunctions on the real line by

be the sheaf of holomorphic functions on C. Define the hyperfunctions on the real line by

the first local cohomology group.

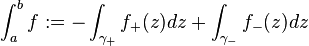

Concretely, let C+ and C− be the upper half-plane and lower half-plane respectively. Then

so

Since the zeroth cohomology group of any sheaf is simply the global sections of that sheaf, we see that a hyperfunction is a pair of holomorphic functions one each on the upper and lower complex halfplane modulo entire holomorphic functions.

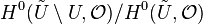

More generally one can define  for any open set

for any open set  as the quotient

as the quotient  where

where  is any open set with

is any open set with  . One can show that this definition does not depend on the choice of

. One can show that this definition does not depend on the choice of  giving another reason to think of hyperfunctions as "boundary values" of holomorphic functions.

giving another reason to think of hyperfunctions as "boundary values" of holomorphic functions.

Examples

- If f is any holomorphic function on the whole complex plane, then the restriction of f to the real axis is a hyperfunction, represented by either (f, 0) or (0, −f).

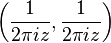

- The Heaviside step function can be represented as

.

.

- The Dirac delta "function" is represented by

. This is really a restatement of Cauchy's integral formula. To verify it one can calculate the integration of f just below the real line, and subtract integration of g just above the real line - both from left to right. Note that the hyperfunction can be non-trivial, even if the components are analytic continuation of the same function. Also this can be easily checked by differentiating the Heaviside function.

. This is really a restatement of Cauchy's integral formula. To verify it one can calculate the integration of f just below the real line, and subtract integration of g just above the real line - both from left to right. Note that the hyperfunction can be non-trivial, even if the components are analytic continuation of the same function. Also this can be easily checked by differentiating the Heaviside function.

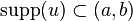

- If g is a continuous function (or more generally a distribution) on the real line with support contained in a bounded interval I, then g corresponds to the hyperfunction (f, −f), where f is a holomorphic function on the complement of I defined by

- This function f jumps in value by g(x) when crossing the real axis at the point x. The formula for f follows from the previous example by writing g as the convolution of itself with the Dirac delta function.

- Using a partition of unity one can write any continuous function (distribution) as a locally finite sum of functions (distributions) with compact support. This can be exploited to extend the above embedding to an embedding

.

.

- If f is any function that is holomorphic everywhere except for an essential singularity at 0 (for example, e1/z), then (f, −f) is a hyperfunction with support 0 that is not a distribution. If f has a pole of finite order at 0 then (f, −f) is a distribution, so when f has an essential singularity then (f,−f) looks like a "distribution of infinite order" at 0. (Note that distributions always have finite order at any point.)

Operations on hyperfunctions

Let  be any open subset.

be any open subset.

- By definition

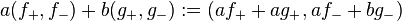

is a vector space such that addition and multiplication with complex numbers are well-defined. Explicitly:

is a vector space such that addition and multiplication with complex numbers are well-defined. Explicitly:

- The obvious restriction maps turn

into a sheaf (which is in fact flabby).

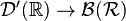

into a sheaf (which is in fact flabby). - Multiplication with real analytic functions

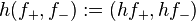

and differentiation are well-defined:

and differentiation are well-defined:

,

,

- With these definitions

becomes a D-module and the embedding

becomes a D-module and the embedding  is a morphism of D-modules.

is a morphism of D-modules.

- A point

is called a holomorphic point of

is called a holomorphic point of  if f restricts to a real analytic function in some small neighbourhood of a. If

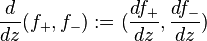

if f restricts to a real analytic function in some small neighbourhood of a. If  are two holomorphic points, then integration is well-defined:

are two holomorphic points, then integration is well-defined:

- where

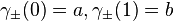

![\textstyle\gamma_{\pm}:[0,1] \to \mathbb{C}^{\pm}](../I/m/aee2398285a89b1de56d96f3b4d80491.png) are arbitrary curves with

are arbitrary curves with  . The integrals are independent of the choice of these curves because the upper and lower half plane are simply connected.

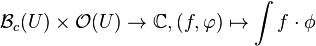

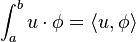

. The integrals are independent of the choice of these curves because the upper and lower half plane are simply connected. - Via bilinear form

associates to each hyperfunction with compact support a continuous linear function on

associates to each hyperfunction with compact support a continuous linear function on  . This induces an identification of the dual space

. This induces an identification of the dual space  with the space of hyperfunctions with compact support. A special case worth considering is the case of continuous functions or distributions with compact support: If one considers

with the space of hyperfunctions with compact support. A special case worth considering is the case of continuous functions or distributions with compact support: If one considers  (or

(or  ) as a subset of

) as a subset of  via the embedding from above, then this computes exactly the traditional Lebesgue-integral. Furthermore: If

via the embedding from above, then this computes exactly the traditional Lebesgue-integral. Furthermore: If  is a distribution with compact support and

is a distribution with compact support and  is a real analytic function, and

is a real analytic function, and  then

then  . Thus this notion of integration gives a precise meaning to formal expressions like

. Thus this notion of integration gives a precise meaning to formal expressions like  which are undefined in the usual sense. Moreover: Because the real analytic functions are dense in

which are undefined in the usual sense. Moreover: Because the real analytic functions are dense in  ,

,  is a subspace of

is a subspace of  . This is an alternative description of the same embedding

. This is an alternative description of the same embedding  .

.

- If

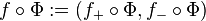

is a real analytic map between open sets of

is a real analytic map between open sets of  , then composition with

, then composition with  is a well-defined operator

is a well-defined operator  :

:

See also

References

- Hörmander, Lars (2003), The analysis of linear partial differential operators, Volume I: Distribution theory and Fourier analysis, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-00662-1.

- Sato, Mikio (1959), "Theory of Hyperfunctions, I", Journal of the Faculty of Science, University of Tokyo. Sect. 1, Mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry 8 (1): 139–193, MR 0114124, hdl:2261/6027.

- Sato, Mikio (1960), "Theory of Hyperfunctions, II", Journal of the Faculty of Science, University of Tokyo. Sect. 1, Mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry 8 (2): 387–437, MR 0132392, hdl:2261/6031.

![H^1_{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{C}, \mathcal{O}) = \left [ H^0(\mathbf{C}^+, \mathcal{O}) \oplus H^0(\mathbf{C}^-, \mathcal{O}) \right ] /H^0(\mathbf{C}, \mathcal{O}).](../I/m/b719e91dae08dba88413cd02e9c88145.png)