Hydrochlorothiazide

| |

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

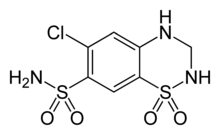

| 6-chloro-1,1-dioxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine-7-sulfonamide | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Apo-hydro, Aquazide h, Dichlotride among others, Oretic |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682571 |

| |

| |

| Oral (capsules, tablets, oral solution) | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variably absorbed from GI tract. Bioavailability ~ 70% |

| Metabolism | does not undergo significant metabolism (>95% excreted unchanged in urine)[1] |

| Half-life | 5.6–14.8 h |

| Excretion | Primarily excreted unchanged in urine |

| Identifiers | |

|

58-93-5 | |

| C03AA03 | |

| PubChem | CID 3639 |

| DrugBank |

DB00999 |

| ChemSpider |

3513 |

| UNII |

0J48LPH2TH |

| KEGG |

D00340 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:5778 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL435 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C7H8ClN3O4S2 |

| 297.74 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Hydrochlorothiazide (abbreviated HCTZ, HCT, or HZT), is a diuretic medication often used to treat high blood pressure and swelling due to fluid build up.[2] Other uses include diabetes insipidus, renal tubular acidosis, and to decrease the risk of kidney stones in those with high calcium level in the urine.[2] For high blood pressure it is often recommended as a first line treatment.[2][3] HCTZ is taken by mouth and may be combined with other blood pressure medications as a single pill to increase the effectiveness.[2]

Potential side effects include poor kidney function, electrolyte imbalances especially low blood potassium and less commonly low blood sodium, gout, high blood sugar, and feeling faint initially upon standing up.[2] While allergies to HCTZ are reported to occur more often in those with allergies to sulfa drugs this association is not well supported.[2] It may be used during pregnancy but is not a first line medication in this group.[2]

It is in the thiazide medication class and acts by decreasing the kidneys' ability to retain water.[2] This initially reduces blood volume, decreasing blood return to the heart and thus cardiac output.[4] Long term, however, it is believed to lower peripheral vascular resistance.[4]

Two companies, Merck and Ciba, state they discovered the medication which became commercially available in 1959.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[6] In 2008 it was the second most commonly used blood pressure medication in the United States.[4] It is available as a generic drug[2] and is not very expensive.[7]

Medical uses

Hydrochlorothiazide is frequently used for the treatment of hypertension, congestive heart failure, symptomatic edema, diabetes insipidus, renal tubular acidosis.[2] It is also used for the prevention of kidney stones in those who have high levels of calcium in their urine.[2]

Most of the research supporting the use of thiazide diuretics in hypertension was done using chlorthalidone, a different medication in the same class. Some more recent studies have suggested that chlorthalidone might be the more effective thiazide diuretic.[8]

It is also sometimes used for treatment of hypoparathyroidism,[9] hypercalciuria, Dent's disease, and Ménière's disease. For diabetes insipidus, the effect of thiazide diuretics is presumably mediated by a hypovolemia-induced increase in proximal sodium and water reabsorption, thereby diminishing water delivery to the ADH-sensitive sites in the collecting tubules and increasing the urine output.

Thiazides are also used in the treatment of osteoporosis. Thiazides decrease mineral bone loss by promoting calcium retention in the kidney, and by directly stimulating osteoblast differentiation and bone mineral formation.[10]

It may be given together with other antihypertensive agents in fixed combination preparations, such as in hydrochlorothiazide/losartan.

Adverse effects

- Hypokalemia, or low blood levels of potassium are an occasional side effect. It can be usually prevented by potassium supplements or by combining hydrochlorothiazide with a potassium-sparing diuretic.

- Other disturbances in the levels of serum electrolytes including hypomagnesemia (low magnesium), hyponatremia (low sodium), and hypercalcemia (high calcium).

- Hyperuricemia, high levels of uric acid in the blood.

- Hyperglycemia, high blood sugar.

- Hyperlipidemia, high cholesterol and triglycerides.

- Headache

- Nausea/vomiting

- Photosensitivity

- Weight gain

- Gout

- Pancreatitis

These side effects increase with the dose of the medication and are most common at doses of greater than 25 mg per day.

Package inserts, based on case reports and observational studies, have reported that an allergy to a sulfa drug predisposes the patient to cross sensitivity to a thiazide diuretic. A 2005 review of the literature did not find support for this cross-sensitivity.[11]

Mechanism of action

Hydrochlorothiazide belongs to thiazide class of diuretics. It reduces blood volume by acting on the kidneys to reduce sodium (Na) reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule. The major site of action in the nephron appears on an electroneutral Na+-Cl− co-transporter by competing for the chloride site on the transporter. By impairing Na transport in the distal convoluted tubule, hydrochlorothiazide induces a natriuresis and concomitant water loss. Thiazides increase the reabsorption of calcium in this segment in a manner unrelated to sodium transport.[12] Additionally, by other mechanisms, HCTZ is believed to lower peripheral vascular resistance.[13]

Society and culture

%2C_Singapore_-_20150210.jpg)

Brand names

Hydrochlorothiazide is sold both as a generic drug and under a large number of brand names, including BP Zide 12.5 & 25 (Stadmed), Apo-Hydro, Aquazide H,Dichlotride, Hydrodiuril, HydroSaluric, Hydrochlorot, Microzide, Esidrex, and Oretic.

Hydrochlorothiazide is also used in combination with many other classes of hypertensive drugs such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta blockers. These are sold under brand names including Diovan HCT, Zestoretic, Ziac, Benicar HCT, Olmy-H, Atacand HCT, and Lotensin HCT, Temax-H and others.

Sport

Hydrochlorothiazide was detected in the urine of the Russian cyclist Alexandr Kolobnev during the 2011 Tour de France.[14] Kolobnev was the only cyclist to leave the 2011 race in connection with adverse findings at a doping control.[15] While hydrochlorothiazide is not itself a performance-enhancing drug, it may be used to mask the use of performance-enhancing drugs, and is classed by the World Anti-Doping Agency as a "specified substance". Kolobnev was subsequently cleared of all charges of intentional doping.[16][17]

See also

- Benicar HCT

- Diovan HCT

References

- ↑ Beermann B, Groschinsky-Grind M, Rosén A. (1976). "Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of hydrochlorothiazide". Clin Pharmacol Ther 19 (5 (Pt 1)): 531–7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 "Hydrochlorothiazide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Jan 2015.

- ↑ Wright, JM; Musini, VM (8 July 2009). "First-line drugs for hypertension.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (3): CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2. PMID 19588327.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Duarte JD, Cooper-DeHoff RM (June 2010). "Mechanisms for blood pressure lowering and metabolic effects of thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics". Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 8 (6): 793–802. doi:10.1586/erc.10.27. PMC 2904515. PMID 20528637.

- ↑ Ravina, Enrique (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1 ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 74. ISBN 9783527326693.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Best drugs to treat high blood pressure The least expensive medications may be the best for many people". http://www.consumerreports.org/''. November 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Messerli, Franz; Makani,Harikrishna; Benjo,Alexandre; Romero,Jorge; Alviar,Carlos; Bangalore,Sripal (2011). "Antihypertensive Efficacy of Hydrochlorothiazide as Evaluated by Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials". J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 57 (5): 590–600. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.053.

- ↑ Mitchell, Deborah. "Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients with Hypoparathyroidism". J Clin Endocrin Metab. Endocrine Society. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Dvorak MM; De Joussineau C; Carter DH et al. (2007). "Thiazide diuretics directly induce osteoblast differentiation and mineralized nodule formation by targeting a NaCl cotransporter in bone". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18 (9): 2509–16. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007030348. PMC 2216427. PMID 17656470.

- ↑ Johnson, KK; Green, DL, Rife, JP, Limon, L (February 2005). "Sulfonamide cross-reactivity: fact or fiction?". The Annals of pharmacotherapy 39 (2): 290–301. doi:10.1345/aph.1E350. PMID 15644481.

- ↑ Uniformed Services University Pharmacology Note Set #3 2010, Lectures #39 & #40, Eric Marks

- ↑ Duarte, JD; Cooper-Dehoff, RM (2010). "Mechanisms for blood pressure lowering and metabolic effects of thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics". Expert review of cardiovascular therapy 8 (6): 793–802. doi:10.1586/erc.10.27. PMC 2904515. PMID 20528637. NIHMSID: NIHMS215063

- ↑ "Tour de France: Alexandr Kolobnev positive for banned diuretic". Velonation. 2011-07-11. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ↑ "Kolobnev denies knowledge of doping product, says not fired by Katusha". Velonation. 2011-07-12. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ↑ "Press release: Adverse Analytical Finding for Kolobnev". Union Cycliste Internationale. 2011-07-11. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ↑ "Kolobnev Tour de France's first doping case". Cycling News (Bath, UK: Future Publishing Limited). 2011-07-11. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

External links

- NIH medlineplus druginfo

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Hydrochlorothiazide

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||