Hutong

.jpg)

Hutongs (simplified Chinese: 胡同; traditional Chinese: 衚衕; pinyin: hútòng; Wade–Giles: hu2-t'ung4) are a type of narrow streets or alleys, commonly associated with northern Chinese cities, most prominently Beijing.

In Beijing, hutongs are alleys formed by lines of siheyuan, traditional courtyard residences.[1] Many neighbourhoods were formed by joining one siheyuan to another to form a hutong, and then joining one hutong to another. The word hutong is also used to refer to such neighbourhoods.

Since the mid-20th century, the number of Beijing hutongs has dropped dramatically as they are demolished to make way for new roads and buildings. More recently, some hutongs have been designated as protected areas in an attempt to preserve this aspect of Chinese cultural history.

Historical hutongs

During China’s dynastic period, emperors planned the city of Beijing and arranged the residential areas according to the social classes of the Zhou Dynasty (1027 - 256 BC). The term "hutong" appeared first during the Yuan Dynasty, and is a term of Mongolian origin meaning "town".[2]

In the Ming Dynasty (early 15th century) the center was the Forbidden City, surrounded in concentric circles by the Inner City and Outer City. Citizens of higher social status were permitted to live closer to the center of the circles. Aristocrats lived to the east and west of the imperial palace. The large siheyuan of these high-ranking officials and wealthy merchants often featured beautifully carved and painted roof beams and pillars and carefully landscaped gardens. The hutongs they formed were orderly, lined by spacious homes and walled gardens. Farther from the palace, and to its north and south, were the commoners, merchants, artisans, and laborers. Their siheyuan were far smaller in scale and simpler in design and decoration, and the hutongs were narrower.

Nearly all siheyuan had their main buildings and gates facing south for better lighting; thus a majority of hutongs run from east to west. Between the main hutongs, many tiny lanes ran north and south for convenient passage.

Historically, a hutong was also once used as the lowest level of administrative geographical divisions within a city in ancient China, as in the paifang (牌坊) system: the largest division within a city in ancient China was a fang (坊), equivalent to current day precinct. Each fang (坊) was enclosed by walls or fences, and the gates of these enclosures were shut and guarded every night, somewhat like a modern gated community. Each fang (坊) was further divided into several plate or pai (牌), which is equivalent to a current day (unincorporated) community (or neighborhood). Each pai (牌), in turn, contained an area including several hutongs, and during the Ming Dynasty, Beijing was divided into a total of 36 fangs (坊).

However, as the ancient Chinese urban administration division system gave way to population and household divisions instead of geographical divisions, the hutongs were no longer used as the lowest level of administrative geographical division and were replaced with other divisional approaches.

Hutongs in the modern era

At the turn of the 20th century, the Qing court was disintegrating as China’s dynastic era came to an end. The traditional arrangement of hutongs was also affected. Many new hutongs, built haphazardly and with no apparent plan, began to appear on the outskirts of the old city, while the old ones lost their former neat appearance. The social stratification of the residents also began to evaporate, reflecting the collapse of the feudal system.

Many such hutong-like areas have been demolished. During the period of the Republic of China from 1911 to 1948, society was unstable, fraught with civil wars and repeated foreign invasions. Beijing deteriorated, and the conditions of the hutongs worsened. Siheyuans previously owned and occupied by single families were subdivided and shared by many households, with additions tacked on as needed, built with whatever materials were available. The 978 hutongs listed in Qing Dynasty records swelled to 1,330 by 1949. Today, in some hutongs, such as those in Da Shi Lan, the conditions remain poor.[3]

Decline of hutongs

Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many of the old hutongs of Beijing disappeared, replaced by wide boulevards and high rises. Many residents left the lanes where their families lived for generations for apartment buildings with modern amenities. In Xicheng District, for example, nearly 200 hutongs out of the 820 it held in 1949 have disappeared.

However, many of Beijing’s ancient hutongs still stand, and a number of them have been designated protected areas. The older neighborhoods survive today, offering a glimpse of life in the capital city as it has been for generations.

Many hutongs, some several hundred years old, in the vicinity of the Bell Tower and Drum Tower and Shichahai Lake are preserved amongst recreated contemporary two- and three-storey versions.[4][3] This area abounds with tourists, many of which tour the quarter in pedicabs.

Today, some hutongs are home to celebrities and even officials. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests, Zhao Ziyang spent his fifteen years of house arrest inside a hutong. Zhao's hutong had previously been occupied by one of Empress Dowager Cixi's hairdressers.[5]

Hutong culture

Hutongs represent an important cultural element of the city of Beijing. Thanks to Beijing’s long history and status as capital for six dynasties, almost every hutong has its anecdotes, and some are even associated with historic events. In contrast to the court life and elite culture represented by the Forbidden City, Summer Palace, and the Temple of Heaven, the hutongs reflect the culture of grassroots Beijingers. The hutongs are residential neighborhoods which still form the heart of Old Beijing. A virtual tour of one of Beijing's Hutong's can be found here.

Other information

Each Hutong has a name. Some have had only one name since their creation, while others have had several throughout their history.

Many hutongs were named after their location, or a local landmark or business, such as:

- City gates, such as Inner Xizhimen Hutong, indicating this hutong is located in the "Xizhimen Nei", or "Xizhimen Within", neighbourhood, which is on the city side of Xizhimen Gate, a gate on the city wall.

- Markets and businesses, such as Yangshi Hutong (Yangshi literally means sheep market), or Yizi Hutong (a local term for soap is yizi)

- Temples, such as Guanyinsi Hutong (Guanyinsi is the Kuan-yin Temple)

- Local features, such as Liushu Hutong (Liushu means willow), which was originally named "Liushujing Hutong", litearlly "Willow Tree Well Hutong", after a local well.

Some hutongs were named after people, such as Mengduan Hutong (named after Meng Duan, a mayor of Beijing in the Ming Dynasty whose residence was in this hutong).

Others were given an auspicious name, with words with generic positive attributes, such as Xiqing Hutong (Xiqing means happy)

Hutongs sharing a name, or longer hutongs divided into sections, are often identified by direction. for example, there are three Hongmen Hutong ("Red Gate Hutong"), being the West Hongmen Hutong, the East Hongmen Hutong, and the South Hongmen Hutong (all three hutongs have been completely obliterated as of 2011 and no longer exist).

While most Beijing hutongs are straight, Jiudaowan (九道弯, literally "Nine Turns") Hutong turns nineteen times.

At its narrowest section, Qianshi Hutong near Qianmen (Front Gate) is only 40 centimeters wide.

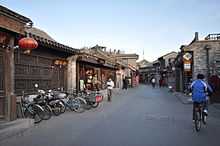

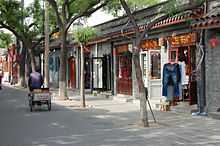

Gallery

- hutongs in Beijing

-

-

A noodle shop

-

-

No. 6 Fuqiang Hutong, successively home to two deposed leaders: Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang

-

-

See also

References

- ↑ Michael Meyer. "The Death and Life of Old Beijing".

- ↑ Kane, David (2006). The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage. Tuttle Publishing. p. 191. ISBN 9780804838535. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Booth, Robert; Watts, Jonathan (June 5, 2008). "Charles takes on China to save Ming dynasty houses from Beijing's concrete carbuncles". The Guardian (London).

- ↑ http://archrecord.construction.com/features/beijing/warpspeed/0807beijing-3.asp

- ↑ Becker, Jasper. "Zhao Ziyang: Chinese Leader Who 'Came too Late' to Tiananmen Square". The Independent. January 18 2005. Retrieved September 18 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hutong. |

- Preservation of Beijing's Hutongs: An Alternate Approach at the Wayback Machine (archived January 6, 2011)

- "'Real people' transition in China's old hutongs," USA Today, August 14, 2008

- Hutongs pictures in Liulichang, Qianmen and Panjiayuan

- China Daily article on hutong research

- Learning from the Hutong of Beijing and the Lilong of Shanghai

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Hutong of Beijing(The Chinese beautiful girl who plays at Hutong)YouTube