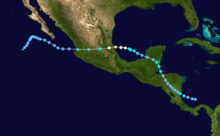

Hurricane Gert (1993)

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Gert approaching the Mexican coastline | |

| Formed | September 14, 1993 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 26, 1993 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 970 mbar (hPa); 28.64 inHg |

| Fatalities | 90 dead, 43 missing |

| Damage | $170 million (1993 USD) |

| Areas affected | Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Belize, Mexico |

| Part of the 1993 Atlantic hurricane season, 1993 Pacific hurricane season | |

Hurricane Gert was a large tropical cyclone that caused significant flood damage throughout Central America and Mexico in September 1993. The seventh named storm and third hurricane of the annual hurricane season, Gert originated as a tropical depression from a tropical wave over the southwestern Caribbean Sea on September 14. The following day, the cyclone briefly attained tropical storm strength before moving ashore in Nicaragua. It proceeded through Honduras, reorganizing into a tropical storm over the Gulf of Honduras on September 17, but weakened back to a depression upon entering Belize the next day. After crossing the Yucatán Peninsula, Gert emerged over warm water in the Bay of Campeche, which allowed it to strengthen into a Category 2 hurricane on September 20. The hurricane made a final landfall on the Gulf Coast of Mexico near Tuxpan, Veracruz, with peak sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). The rugged terrain quickly disrupted the cyclone's structure, and Gert entered the Pacific Ocean as a tropical depression near the state of Nayarit on September 21. There, it briefly redeveloped a few strong thunderstorms before dissipating over open water five days later.

Gert's broad wind circulation produced widespread and heavy rainfall across Central America, which, combined with saturated soil from Tropical Storm Bret's passage a month earlier, caused significant flooding of property and crops. Although the storm's highest winds occurred upon landfall in Mexico, the worst effects in the country were due to torrential rain. Following the overflow of several major rivers, deep flood waters submerged extensive parts of Veracruz and Tamaulipas, forcing thousands to evacuate. The heaviest rainfall occurred farther inland over the mountainous region of San Luis Potosí, where as much as 31.41 inches (798 mm) of precipitation were measured. In the wake of the disaster, the road networks across the affected countries were severely disrupted, and thousands of people became homeless. The storm killed 90 people, left 43 missing, and caused over $170 million (1993 USD) in damage.

Meteorological history

A tropical wave—an area of low pressure oriented north to south—moved off the African coast well south of Dakar on September 5, 1993, and tracked rapidly westward across the tropical Atlantic. Positioned at a relatively low latitude, the wave interacted with the Intertropical Convergence Zone, allowing for the enhancement of convection in its vicinity. It developed a weak low-pressure center at sea level, which passed directly over Trinidad on September 11. The majority of the system subsequently moved inland along the northern coast of South America, although it maintained its identity and emerged over the southwestern Caribbean Sea on September 13.[1] Owing to favorable tropospheric conditions aloft, the system began showing signs of development as the deep convection organized into well-defined curved rainbands. Based on the increase in organization and the presence of a surface circulation, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) classified it as a tropical depression at 1800 UTC on September 14, about 105 mi (165 km) north of the northern coast of Panama.[1][2]

The depression retained a large circulation during its formative stages, indicated by both satellite observations and data from rawinsondes in the region.[1] Its cloud pattern continued to coalesce, and the NHC upgraded it to Tropical Storm Gert at 0900 UTC on September 15.[3] After tracking west-northwestward, the center of the storm moved ashore near Bluefields, Nicaragua, around 1800 UTC that day, with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h).[1][4] An interaction with land impeded further development, and Gert weakened back to a tropical depression six hours later. Despite the center being inland for nearly two days, a large part of the circulation stayed over the adjacent Caribbean and Pacific waters. This allowed Gert to remain a tropical cyclone while trekking northwestward through Nicaragua and Honduras,[1] defying the NHC's repeated forecasts of its dissipation over land.[5][6]

The cyclone moved into the Gulf of Honduras on September 17, restrengthening into a tropical storm soon thereafter. That same day, a mid- to upper-level trough over the eastern Gulf of Mexico caused the storm to turn to the north-northwest. Gert's duration over water was short lived; the storm moved back inland near Belize City the next day, granting it minimal opportunity for additional strengthening. Once inland, Gert began to feel the effects of a high-pressure ridge to its northwest, causing the storm to again turn west-northwest.[7] After crossing the Yucatán Peninsula and decreasing in organization,[8] it entered the Bay of Campeche offshore Champotón, Campeche, as a tropical depression late on September 18.[4][7] Gert restrengthened over open waters, as light wind shear allowed its deep convection to consolidate; by 0600 UTC the next day, the cyclone once again became a tropical storm.[9] On September 20, data from a United States Air Force aircraft indicated that the storm had further strengthened into a hurricane with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). Gert veered toward the west and slowed slightly owing to a shortwave trough to its north,[10] giving it more time to organize over water.[7] The cyclone attained its peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale, with winds of 100 mph (165 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 970 mbar (hPa; 28.64 inHg).[7]

Around 2100 UTC on September 20, Gert made a final landfall at peak intensity on the coast of Mexico, just north of Tuxpan, Veracruz. Inland, the hurricane accelerated and weakened rapidly over the mountainous region of the Sierra Madre Oriental, diminishing to a tropical depression by September 21. Despite the degeneration, the large circulation remained intact as it crossed the country. Gert exited the coast of Nayarit and entered the Pacific Ocean later that day, where the NHC reclassified it as Tropical Depression Fourteen-E.[4][7] The remaining deep convection waxed and waned in intensity; satellite observations indicated the depression could have briefly been a tropical storm on September 22. It continued a west to west-northwestward motion for two days, though low-level flow steered it toward the southwest after the convection diminished. There was no redevelopment due to cool sea temperatures, and the system dissipated at sea on September 26.[11][12]

Preparations

After confirming the development of a tropical depression, authorities in Costa Rica issued a green alert[nb 1] for coastal regions on September 14.[14] The following day, a tropical storm warning was issued for the Atlantic coast of the country.[15] National television and radio stations broadcast warning messages to the public, and emergency crews were dispatched in case conditions were to warrant intervention. This helped with the effective and timely clearing of hospitals, as well as the evacuation of residents in high-risk zones.[14] A tropical storm warning was posted for the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua on September 15, extending south from Puerto Cabezas to the adjacent islands.[15] In Honduras, early storm warnings allowed several hundred residents to evacuate well ahead of Gert's arrival.[16] Once it became evident that the storm would strike the Yucatán Peninsula, coastal areas from Belize northward to Cozumel, Mexico were placed under a tropical storm warning on September 17 until Gert's landfall the next day.[4][15]

While Gert was still located over the peninsula, the government of Mexico issued a tropical storm watch for the Gulf Coast from the city of Veracruz northward to Soto la Marina, Tamaulipas. By September 18, it had been upgraded to a tropical storm warning and extended southward to Minatitlán, although the initial watch area was placed under a hurricane watch after Gert showed signs of strengthening. The next day, the tropical storm watch from Soto La Marina to Nautla was upgraded to a hurricane warning as it became clearer where Gert would make landfall.[4][15] Prior to impact, several ports along the Gulf Coast halted their operations, and people living in risk zones were evacuated.[17] All warnings and watches were discontinued after the hurricane moved inland.[15]

Impact

| Country | Deaths | Missing |

|---|---|---|

| Honduras | 27 | 12 |

| Nicaragua | 11 | 27 |

| El Salvador | 5 | 4 |

| Costa Rica | 1 | 0 |

| Guatemala | 1 | 0 |

| Mexico | 45 | 0 |

| Total | 90 | 43 |

Gert was a large tropical cyclone for most of its lifespan; it always remained close enough to the coast to restrengthen and redevelop strong thunderstorms. As a result, the storm produced heavy rainfall over a large area, causing extensive flooding and mudslides from Central America to Mexico. The disaster resulted in at least 90 deaths; damage to roads, crop, property, and vegetation surmounted $170 million.[nb 2]

Costa Rica

Although Gert's center remained off the coast of Costa Rica, its large circulation produced brisk winds and heavy rainfall across the country. A local weather station recorded 13.1 in (332 mm) of rain during the passage of the storm.[18] Geologically, the hardest-hit regions consisted of sedimentary layers with poor hydraulic conductivity and were therefore prone to soil saturation.[19] The initial rainfall caused a significant water rise in many rivers, which exacerbated the flood threat. The imminent overflow of the Tempisque River prompted a wide-scale evacuation of residents from adjacent areas; however, the river crested gradually without major consequences. Following hours of prolonged downpours, many Pacific regions such as Quepos, Pérez Zeledón, and Osa experienced extensive flooding and localized landslides, inflicting heavy damage to roads and bridges.[14] The floods destroyed about 500 acres (2.0 km2) of banana crop and caused moderate damage to oil palm plantations. Small-scale crop farmers of reed, maize, beans, and rice were also greatly affected. The storm disrupted local fishing, and several small boats in Quepos sustained damage.[20] High winds brought great destruction to the Manuel Antonio National Park, vastly impacting the tourism-driven economy in Quepos.[19]

Gert left moderate property damage in its wake; it demolished 27 homes and damaged 659, mostly because of flooding. Overall monetary losses surmounted $3.1 million, of which over $1.7 million was incurred by damage to the infrastructure.[21] Roughly 1,000 people sought shelter during the storm, but owing to the timely preparations in the country, only one cardiac arrest fatality was attributable to Gert when a landslide buried a home.[14][22]

Nicaragua

The storm moved ashore in Nicaragua a month after Tropical Storm Bret's passage through the country, causing excessive rainfall over already saturated areas.[23] In spite of striking the Atlantic coast, Gert produced the largest amounts of precipitation over northern and Pacific coastal areas. A maximum of 17.8 in (452 mm) fell at Corinto; other high totals include 17.6 in (447 mm) at Chinandega and 17.5 in (444 mm) at León. The capital of Managua recorded 9.8 in (249 mm) of rain during the event.[24] Sustained winds from the storm reached no more than 40 mph (65 km/h) upon landfall near Bluefields,[4] though they generated high waves of up to 12 ft (3.7 m) offshore. After weakening to a depression inland, Gert continued to produce moderate gales along its path through the country.[25]

Off the coast near Big Corn Island, rough surf and winds destroyed nine fishing boats. Two canoes with an unknown number of occupants disappeared at sea. Gert produced significant coastal flooding upon moving ashore near Bluefields and Tasbapauni, prompting about 1,000 residents and hundreds of indigenous Miskito villagers to evacuate.[25] Farther inland, prolonged heavy rain caused numerous rivers to overflow, which in turn led to destructive freshwater flooding. A river near Rama rose to 32 ft (10 m) above its normal stage, displacing 3,900 people and leaving about 80 percent of the town submerged. Several communities in the Rivas Department were inundated by discharge from a river near Rivas city, while Cárdenas, a coastal community along the border with Costa Rica, experienced several days of heavy rain. Throughout the Boaco Department, similar flooding killed 5 people and affected 6,000 others.[26] Landslides caused additional damage to bridges and roads, disrupting local transportation.[23] At least 59 houses were destroyed, and about 225 experienced damage across 14 of the country's departments.[23][26] In addition, Gert was responsible for considerable economic losses and damage to infrastructure.[26] It affected 10,408 households to varying degrees, killing 11 people and leaving 27 others missing.[26][27] Since flood damage from Tropical Storm Bret had occurred just one month earlier, an exclusive damage total for Gert is unavailable. The two storms inflicted about $10.7 million in damage, primarily to private property.[28]

Honduras

Although it had weakened to a depression, Gert continued to drop significant amounts of rain while tracking across Honduras. In Tegucigalpa, at least 6.77 in (172 mm) of rain were recorded.[29] Destructive floods swept through 13 of the country's 18 departments, including much of northern Honduras and the Mosquitia Region, which had already suffered losses from Tropical Storm Bret in the previous month. The additional flooding from Gert affected 24,000 people in the region and made communication with surrounding areas nearly impossible.[16] Elsewhere, the Ulúa River and several other major rivers overflowed because of the excessive rain;[30] rivers across Sula Valley in particular sustained heavy damage to their banks, causing much of San Pedro Sula—the country's second-largest city—and adjacent municipalities in the Cortés Department to become inundated. The rising water prompted many residents to evacuate. At the height of the flooding, the Ramón Villeda Morales International Airport halted all of its operations.[16]

The storm greatly devastated Puerto Cortés, one of the most important port cities in Central America.[31] Elsewhere in the Cortés Department, the overflow of a river in Choloma triggered widespread floods;[30] landslides in that area alone claimed the lives of six people.[32] The country's agricultural sector sustained heavy flood damage to about 5,700 acres (23 km2) of plantations in low-lying areas, including banana, sugar, and citrus.[16][33] In all, Gert wrought $10 million worth of damage to roads, bridges, and property.[29] The disaster directly affected 67,447 people, of which roughly 60 percent had to evacuate their homes. In its final public statement, the government of Honduras confirmed 27 fatalities, though 12 missing persons remain unaccounted for.[16]

Elsewhere in Central America

While passing through Central America, Gert generated an increase in cloudiness and showers across El Salvador.[34] High winds uprooted trees or snapped their limbs, damaging power lines and causing power outages. In one community, heavy downpours triggered damaging mudslides along a major highway.[27] The Río Grande de San Miguel crested rapidly, causing an excess of water discharge just southwest of Usulután.[34] As a consequence, about 2,500 acres (10 km2) of crop from adjacent plantations sustained flood damage. Several other areas reported significant losses due to the flooding, including San Marcos and San Vicente; some property and road damage also occurred in San Miguel.[27] Although fishing operations were suspended at the height the storm, four local fishermen disappeared at sea.[34] The weather system affected nearly 8,000 residents in the country;[27] officials reported twelve destroyed homes and five deaths in its wake.[34]

Torrential rains from Gert affected about 20,000 people and killed one girl in Guatemala. The storm led to considerable agricultural losses for the country, though there were no specific reports of damage.[27] Gert moved ashore near Belize City as a minimal tropical storm, dropping heavy rainfall in coastal areas. Just offshore, a weather station on Hunting Caye recorded 9.5 in (241 mm) of precipitation during the event.[35] Despite the rain, only minor flooding occurred in Belize City.[36]

Mexico

While crossing the Yucatán Peninsula as a minimal storm, Gert dropped considerable rainfall in Quintana Roo; a 24-hour accumulation of 7.4 in (188 mm) was recorded at Chetumal, although much higher localized totals of around 15 in (380 mm) fell elsewhere in the state.[12][29] Gusty winds briefly buffeted the coast during the storm's landfall, with a maximum wind speed of 44 mph (70 km/h) recorded in Chetumal.[7] Damage was limited to localized floods, however, cutting off one road to traffic. In addition, the flooding forced the inhabitants of some low-lying areas in Chetumal and Felipe Carrillo Puerto to evacuate to higher ground.[37] Scattered showers caused light flooding in parts of the state of Campeche, such as Ciudad del Carmen.[38]

High gales and large waves battered wide stretches of coastline in the states of Tamaulipas and Veracruz upon Gert's landfall, although hurricane-force winds were largely confined to areas within the cyclone's southern eyewall.[29][39] Tuxpan, just south of where the eye moved ashore,[7] recorded wind velocities of over 100 mph (160 km/h), while 80 mph (130 km/h) gusts occurred farther south in Poza Rica. To the north, winds reached 55 mph (90 km/h) in Tampico, Tamaulipas. Despite the severity of the winds, the worst of Gert was due to orographic lift when its broad circulation interacted with the eastern side of the Sierra Madre Oriental, generating extreme precipitation over much of the Huasteca region.[29] As much as 31.41 in (798 mm) of rain were recorded in Aquismón, San Luis Potosí, while Tempoal in Veracruz reported a 24-hour total of 13.35 in (339 mm) from the storm.[12][29]

The first signs of impact were from high winds on September 20, which uprooted trees and tore off residential roofs in Tuxpan, Naranjos, Cerro Azul, and Poza Rica.[40] Following Gert's extreme rains, catastrophic flooding struck Mexico's Huasteca region over a period of several days as many of its rivers rose to critical levels. Initially, in Veracruz, the imminent overflow of the Tempoal, Moctezuma and Calabozo rivers prompted thousands of residents from the municipalities of Tempoal, El Higo, and Platón Sánchez to flee their homes. The Calabozo eventually topped its banks, cutting the village of Platón Sánchez off from the outside world. By far the most devastating, however, was the overflow of the Pánuco River, which runs from the Valley of Mexico through the municipality of Pánuco and empties in the gulf, on September 24. Rushing waters swept through 30 of Veracruz's 212 municipalities, totally inundating more than 5,000 homes. El Higo bore the brunt of the flooding, with 90 percent of its residential area submerged.[41] After days of continued heavy rain in Gert's wake, the Pánuco rose to 27.60 ft (8.72 m) above normal by September 27—its highest level in 40 years—and again exceeded its banks, destroying a major levee in Pánuco city and forcing over 8,000 citizens to evacuate.[41][42] The destructive floods reached as far north as southern Tamaulipas, where about 5,000 residents had to evacuate. Half of Tampico city was coated in a deep layer of mud, with scores of structures demolished.[43] Urban areas of Madero and Altamira were also hard hit by the deluge.[44] In total, 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of land around the Pánuco basin and Tampico were under water, including vast amounts of citrus, coffee, corn, maiz, bean, grain, and soy crops. Telephone, water, and electricity services throughout the region were severely disrupted, and numerous communities were isolated due to destroyed bridges and roads.[41][43]

In San Luis Potosí, the agricultural sector suffered great losses after roughly 80 percent of its crop and large amounts of livestock were washed away. Water damage to schools, bridges, and roads was particularly widespread, and 25 people lost their lives in the state.[45] Gert's trail of devastation extended as far inland as Hidalgo, where 35 rivers burst their banks. The flooding washed away bridges and roads and cut off power, telephone, and water services, creating communication problems for 361 communities. Structural damage in Hidalgo was significant; 4,425 homes, 121 schools, and 49 public buildings were affected across 35 municipalities. About 167,000 acres (680 km2) of farmland became ruined. Fifteen deaths occurred in the state alone, and eight people suffered injuries.[45]

In all, Gert became the worst natural disaster to strike the region in 40 years,[41] affecting an estimated 60,000 people and leaving 29,075 houses and 667,000 acres (2,700 km2) of crop damaged or destroyed across Mexico.[29][41] The associated monetary losses totaled $156 million, and the death toll stood at 45.[29][43]

Aftermath

Central America

Because of Gert's effects, the government of Costa Rica declared a national emergency for the country on September 16, 1993.[19] Emergency crews were dispatched to assess damage and distribute life supplies to the affected population; this included 90,940 lbs (41,250 kg) of food, 1,422 mattresses, and 1,350 blankets.[14] In its wake, the disrupted road network across the affected regions impacted the local agriculture, tourism, and commerce.[20] The obstruction of the major Pan-American Highway, which connects the central region to the south of the country, resulted in considerable economic losses. Following the extensive flood damage to farmland, many independent crop producers suffered from being unable to partake in subsequent sowings.[20]

Before the arrival of Gert, a state of emergency was in effect for Nicaragua as a result of Tropical Storm Bret. National and regional relief agencies, including the Red Cross, accordingly extended their relief efforts. Although the government did not reappeal for international assistance, several monetary contributions were made by overseas organizations; a transfer channel for cash donations was opened at the Swiss Bank Corporation. The United Nations Development Programme provided $50,000 for the local purchase of fuel, and UNICEF distributed $25,000 worth of household supplies and medicine. The World Food Programme donated approximately 160,000 lbs (72 tonnes) of food supply and offered services of expert in response to the disaster. The federal governments of Japan, Canada, Switzerland, Norway, Germany, and Spain donated a combined $300,000 in aid.[23]

On September 18, the President of Honduras surveyed the affected regions by helicopter, declaring a state of emergency for several municipalities. Although most of the affected population received aid within a few days, the limited road network caused a large delay in relief efforts to the hard-hit Mosquitia Region. By September 28, about 27,000 residents unable to reenter their flooded homes remained in government-owned shelters. Seven weeks later, a temporary housing project was implemented for the 120 families most in need. Countrywide, sewage systems, water works, and latrines were severely disrupted and in need of rehabilitation. Public health concerns rose in the wake of Gert; the cost of required medicines totaled $208,000. The governments of Japan, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom provided a combined $310,300 for the purchase of relief items. Because of the storm damage, approximately 5,900 families lost their source of income.[16] Following the destruction of its sole water reservoir, much of Puerto Cortés suffered potable water shortages for months in Gert's wake.[31] The storm exacerbated a cholera outbreak in rural areas due to contaminated water supplies.[46]

Mexico

In response to the flood disaster, Red Cross officials immediately began distributing aid to victims. After assessing the situation by helicopter, the President of Mexico declared the Pánuco River basin an emergency zone and initiated search and rescue missions.[43][44] Many homes sustained irreparable damage to their roofs, leaving thousands of residents homeless. The government appealed for international aid, seeking clothes, food, and medical supplies.[43] Five storage centers in Hidalgo provided over 93 million lbs (42,000 tonnes) of food supplies. Across San Luis Potosí, 142,000 lbs (64 tonnes) of chicken, 45,000 pantries, and 76,000 disposable plates were distributed, as well as 50,440 blankets and 6,081 airbeds.[45] Several schools served as shelters for the homeless; sheltered children, elderly, and pregnant or lactating women received $27,000 in milk powder donations.[43][45]

By three weeks after the storm, over 65,000 people had been accommodated in shelters; most of them remained there until flood water levels receded. A grant of $22,000 was made available to purchase roofing sheets for those in urgent need of home repair. The president approved $37.4 million for the reconstruction of roads and housing, as well as the assistance of affected farmers. In Gert's wake, the amount of respiratory disease and skin infection cases rose slightly, although the overall health situation for the country remained well under control.[43]

See also

- Tropical Storm Arlene (1993)

- Tropical Storm Bret (1993)

- Other storms of the same name

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Pasch, Richard J. (1993-11-10). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert: 14-21 September 1993 (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard J. (1993-09-14). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion One (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard J. (1993-09-15). Tropical Storm Gert Discussion Three (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Pasch, Richard J. (1993-11-10). "Table 1: Preliminary best track, Hurricane Gert, 14-21 September 1993". Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert: 14-21 September 1993 (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard J. (1993-10-15). Tropical Depression Gert Discussion Five (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard J. (1993-10-16). Tropical Depression Gert Discussion Nine (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Pasch, Richard J. (1993-11-10). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert: 14-21 September 1993 (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles B. (1993-10-18). Tropical Depression Gert Discussion Sixteen (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ↑ Mayfield, Max (1993-09-19). Tropical Storm Gert Discussion Nineteen (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ Mayfield, Max (1993-09-23). Hurricane Gert Discussion Twenty-Three (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- Rappaport, Edward N.; Wright, Bill (1993-09-19). Hurricane Gert Discussion Twenty-Four (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- ↑ Rappaport, Edward N. (1993-09-29). Preliminary Report Tropical Depression Fourteen-E: 21-26 September 1993 (Report). Tropical Depression Fourteen-E, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Roth, David M. (2010-05-10). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. Camp Springs, Maryland: Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. p. Hurricane Gert/T.D. #14E - September 14–28, 1993. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ "Sistema de Alerta Temprana para Ciclones Tropicales" (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación. p. 21. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Part A: Informe de operaciónes Tormenta Gert". Plan regulador para la reconstrucción de las zonas afectadas por la Tormenta Tropical Gert (PDF) (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica: Comisión Nacional de Emergencias. 1993-09-18. section 3, part A, pp. 2, 3, 7, [9], [15]. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Pasch, Richard J. (1993-11-19). "Table 3: Watch and warning summary, Hurricane Gert". Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert: 14-21 September 1993 (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (September 1993). Honduras Floods Sep 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 4 (Report). Geneva, Switzerland: ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ Gutiérrez, Prisciliano H.; Jiménez, Elias M.; de la Fuente, Rigoberto M.; Mendiola, Rubén Dario S. (December 1993). Las inundaciones causadas por el huracán "Gert" sus efectos en Hidalgo, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas y Veracruz (PAMPHLET) (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: El Sistema Nacional de Proteccion Civil, Secretaria de Gobernation; archived by CENAPRED. p. 12.

- ↑ Fallas, Jorge; Valverde, Carmen (2007). Aplicación de ENOS como indicador de cambios en la precipitación máxima diaria en la cuenca del río Pejibaye y su impacto en inundaciones (PDF). III Congreso Iberoamericano Sobre Desarrollo Y Ambiente 5–9 de noviembre 2007 (in Spanish). Heredia, Costa Rica: Universidad Nacional. p. [20]. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 (Spanish) Plan regular para la reconstrucción de las zonas afectadas por la Tormenta Tropical Gert (PDF) (Report). San José, Costa Rica: Comisión Nacional de Emergencias. September 1993. pp. 2–5. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Tormenta Tropical Gert Resumen Ejecutivo". Plan regulador para la reconstrucción de las zonas afectadas por la Tormenta Tropical Gert (PDF) (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica: Comisión Nacional de Emergencias. 1993. section 2, p. [5]. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ "Informe final de operaciónes Tormenta Gert". Plan regulador para la reconstrucción de las zonas afectadas por la tormenta tropical Gert (PDF) (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica: Comisión Nacional de Emergencias. 1993-09-25. section e, pp. 4, 13. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ↑ "Storm hits two nations". Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida). 1993-09-17. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (1993-09-17). Nicaragua Tropical Storm Aug 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 8 (Report). Geneva, Switzerland: ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ Nicaragua: Assessment of the damage caused by Hurricane Mitch, 1998: Implications for economic and social development and for the environment (PDF) (Report). Santiago, Chile: United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 1999-04-19. p. 12. LC/MEX/L.372. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Otis, John (1993-09-16). "Weaker but blustery Gert inundates Nicaragua coast". The Miami Herald. Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "Estadísticas Específicas por Evento". Nicaragua (PDF). Revisión de eventos históricos importantes: Informe técnico ERN-CAPRA-T2-1 (in Spanish). Análisis probabilista de amenazas y riesgos naturales. Bogotá, Colombia: Evaluación de Riesgos Naturales - América Latina - Consultores en Riesgos y Desastres. pp. 42–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2011-10-06. Hosted by ecapra.org.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Moisa, Ana Maria; Romano, Luis Ernesto; Velis, Louis Armano, ed. (1993). "[Various short articles]" (PDF). Actualidades sobre desastres: Boletin de extensión cultural de CEPRODE: Centro de Protección para Desastres (in Spanish) (San Salvador, El Salvador: Centro de Protección para Desastres) 1 (1). as archived in Comité Técnico Interinstitucional de Desastres, ed. (1993-10-12). "Actividades de las comunidades: la Coquera, los Coquitos, las Atarrayas. Concurso de Pintura Infantil 12 de Octubre 1993" (PDF). Memoria de actividades realizadas en conmemoración al Día Internacional para la Reducción de los Desastres Naturales - DIRDN : 8 al 15 de octubre 1993. San Salvador, El Salvador: Biblioteca Virtual en Salud y Desastres. section 3 "Actividades de las comunidades", p. [8]. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ Osorio, José L. (1994). Impactos de los desastres naturales en Nicaragua (PDF). Sistema Nacional de prevencion y manejo de desastres naturales (in Spanish) (Managua, Nicaragua: Biblioteca Virtual en Salud y Desastres): 33. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 Pasch, Richard J. (1993-11-10). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gert: 14-21 September 1993 (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Lavell, Allan; Franco, Eduardo. Estado, sociedad y gestión de los desastres en América latina (PDF) (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina. pp. 19, 20. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 (Spanish) Iniciativa de Agua y Saneamiento. Puerto Cortés, Honduras: Después de la tempestad... vino la reforma (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. p. 3. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ (Spanish) Diagnostico ambiental de Choloma (PDF) (Report). San Pedro Sula, Honduras: Cámara de Comercio e Industrias de Cortés. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-25. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ Economist Intelligence Unit (1994). Country report: Nicaragua, Honduras. London, United Kingdom: The Unit. p. 31.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Lungo, Mario; Pohl, Lina (2006). "Las acciones de prevención y mitigación de desastres en El Salvador: Un sistema en construcción". In Lungo, Mario; Baires, Sonia. De terremotos, derrumbes, e inundados (PDF) (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina. p. 34. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ Hourly data from Hunting Caye (Report). Hurricane Gert, Hurricane Wallet Digital Archives. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1993. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ WMO bulletin 44. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization. 2005. p. 369.

- ↑ "Capitulo II: Los Entornos". Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Integral Del Estado de Quintana Roo 2000 - 2025 (PDF) (in Spanish). Tomo I: Entornos, Problemática y Estructura Económica de Quintana Roo. Chetumal, Mexico: Centro de Estudios Estratégicos, Universidad de Quintana Roo. volume 1, chapter 2, p. 16. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ Morales, Héctor E.; Ramírez, Lucía G. M.; Espinosa, Martín J.; Mariles, Óscar A. F.; Estrada, David R. M. (December 2008). Aplicación de la metodología para la elaboración de mapas de riesgo por inundaciones costeras por marea de tormenta (PDF). Atlas Nacional de Riesgos (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación. p. 9. ISBN 978-607-7558-15-6. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ "Storm kills 3". Sarasota Herald-Tribune (Sarasota, Florida). 1993-09-22. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- ↑ Ramírez, Mario G. (2006-08-01). "Trayectorias históricas de los ciclones tropicales que impactaron el estado de Veracruz de 1930 al 2005". Scripta Nova: Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish) (Barcelona, Spain: University of Barcelona) 10 (218(15)). ISSN 1138-9788. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 Mansilla, Elizabeth (1994). "La cuenca baja del Pánuco: Un desastre crónico" (PDF). Desastres y Sociedad (in Spanish) (Panama City, Panama: Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina y el Caribe) 3 (2: Desbordes, Inundaciones y Diluvios): 88–90.

- ↑ "1993 Global Register of Extreme Flood Events". Global Active Archive of Large Flood Events. Hanover, New Hampshire: Dartmouth Flood Observatory. July 2003. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 43.6 United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (1993-10-01). Mexico Tropical Storm Oct 1993 UN DHA Situation Reports 1 - 3 (Report). Geneva, Switzerland: ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Gutiérrez, Prisciliano H.; Jiménez, Elias M.; de la Fuente, Rigoberto M.; Mendiola, Rubén Dario S. (December 1993). Las inundaciones causadas por el huracán "Gert" sus efectos en Hidalgo, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas y Veracruz (PAMPHLET) (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: El Sistema Nacional de Proteccion Civil, Secretaria de Gobernation; archived by CENAPRED. pp. 16, 17.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Gutiérrez, Prisciliano H.; Jiménez, Elias M.; de la Fuente, Rigoberto M.; Mendiola, Rubén Dario S. (December 1993). Las inundaciones causadas por el huracán "Gert" sus efectos en Hidalgo, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas y Veracruz (PAMPHLET) (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: El Sistema Nacional de Proteccion Civil, Secretaria de Gobernation; archived by CENAPRED. pp. 14, 15.

- ↑ Citizen News Services (1993-10-13). "Briefly: Citizen News Services|". The Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa, Canada). section A, p. 9.

External links

- The NHC's Storm Wallet Archive for Hurricane Gert

- The NHC's reports on Hurricane Gert and Tropical Depression Fourteen-E

- The WPC's rainfall report on Hurricane Gert and Tropical Depression Fourteen-E

- The 1993 Monthly Weather Review

| |||||||||||||