Human lung

| Lung | |

|---|---|

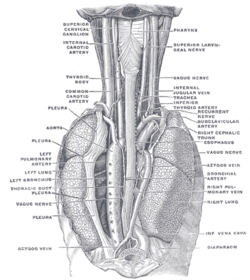

Detailed diagram of the lungs | |

| Details | |

| Latin | pulmo |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.1093-1096 |

| MeSH | A04.411 |

| TA | A06.5.01.001 |

| FMA | 7195 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human lungs are the organs of respiration. Humans have two lungs, a right lung and a left lung. The right lung consists of three lobes while the left lung is slightly smaller consisting of only two lobes (the left lung has a "cardiac notch" allowing space for the heart within the chest).[1] Together, the lungs contain approximately 2,400 kilometres (1,500 mi) of airways and 300 to 500 thousand alveoli.

Estimates of the total surface area of lungs vary from 30-50 square metres up to 70-100 square metres (1076.39 sq ft) (8,4 x 8,4 m) in adults — which might be roughly the same area as one side of a tennis court.[2] However, such estimates may be of limited use unless qualified by a statement of scale at which they are taken (see Coastline paradox and Menger sponge).

Furthermore, if all of the capillaries that surround the alveoli were unwound and laid end to end, they would extend for about 992 kilometres (616 mi). The lungs together weigh approximately 1.3 kilograms (2.9 lb), with the right lung weighing more than the left.

The pleural cavity is the potential space between the two serous membranes, (pleurae) of the lungs; the parietal pleura, lining the inner wall of the thoracic cage, and the visceral pleura, lining the organs themselves–the lungs. The respiratory system includes the conducting zone, which is part of the respiratory tract, that conducts air into the lungs.

The parenchyma of the lung, only relates to the functional alveolar tissue, but the term is often used to refer to all lung tissue, including the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, terminal bronchioles, and all connecting tissues.[3]

Structure

The lungs are located within the thoracic cavity, on either side of the heart and close to the backbone. They are enclosed and protected by the ribcage. The left lung has a lateral indentation which is shaped to accommodate the position of the heart. The right lung is a little shorter than the left lung and this is to accommodate the positioning of the liver. Both lungs have broad bases enabling them to rest on the diaphragm without causing displacement. Each lung near to the centre has a recessed region called the hilum which is the entry point for the root of the lung. (Root here means the anchoring part of a structure.) The bronchi and pulmonary vessels extend from the heart and the trachea to connect each lung by way of the root.

There are three surfaces to the lungs: the costal surface is the outer, thoracic surface which is smooth and convex. This surface area is large and corresponds to the form of the thoracic cavity, being deeper at the back than at the front. The costal surface is in contact with the costal pleura and in specimens that have been hardened in situ, slight grooves are visible which correspond to the overlying ribs.The mediastinal surface of the lung is in contact with the mediastinal pleura and presents the cardiac impression. The diaphragmatic surface of lung is the portion of the lung which borders on the thoracic diaphragm.

Right lung

The right lung is divided into three lobes (as opposed to two lobes on the left), superior, middle, and inferior, by two interlobular fissures:

The right lung has a higher volume, total capacity and weight, than that of the left lung. Although it is 5 cm shorter due to the diaphragm rising higher on the right side to accommodate the liver, it is broader than the left lung due to the cardiac notch of the left lung.

- Fissures

- The lower, oblique fissure, separates the inferior from the middle and superior lobes, and is closely aligned with the fissure in the left lung. Its direction is, however, more vertical, and it cuts the lower border about 7.5 cm. behind its anterior extremity.

- The upper, horizontal fissure, separates the superior from the middle lobe. It begins in the lower fissure near the posterior border of the lung, and, running horizontally forward, cuts the anterior border on a level with the sternal end of the fourth costal cartilage; on the mediastinal surface it may be traced backward to the hilum.

- Lobes

The middle lobe is the smallest lobe of the right lung. It is wedge-shaped, and includes the part of the anterior border, and the anterior part of the base of the lung. The superior and inferior lobes are similar to those of the left lung (which lacks a middle lobe.)

- Impressions

There is a deep concavity on the mediastinal surface called the cardiac impression, which accommodates the pericardium; this is not as pronounced as that on the left lung where the heart projects further. On the same surface, immediately above the hilum, is an arched furrow which accommodates the azygos vein; while running superiorly, and then arching laterally some little distance below the apex, is a wide groove for the superior vena cava and right innominate vein; behind this, and proximal to the apex, is a furrow for the innominate artery.

Behind the hilum and the attachment of the pulmonary ligament is a vertical groove for the esophagus; this groove becomes less distinct below, owing to the inclination of the lower part of the esophagus to the left of the middle line.

In front and to the right of the lower part of the esophageal groove is a deep concavity for the extrapericardiac portion of the thoracic part of the inferior vena cava.

Left lung

The left lung is divided into two lobes, an upper and a lower, by the oblique fissure, which extends from the costal to the mediastinal surface of the lung both above and below the hilum. The left lung, unlike the right does not have a middle lobe. However the term lingula is used to denote a projection of the upper lobe of the left lung that serves as the homologue. This area of the left lobe - the lingula, means little tongue (in Latin) and is often referred to as the tongue in the lung. There are two bronchopulmonary segments of the lingula: superior and inferior. It is thought that the lingula of the left lung is the remnant of the middle lobe, which has been lost through evolution.

- Surfaces

As seen on the surface, this fissure begins on the mediastinal surface of the lung at the upper and posterior part of the hilum, and runs backward and upward to the posterior border, which it crosses at a point about 6 cm. below the apex.

It then extends downward and forward over the costal surface, and reaches the lower border a little behind its anterior extremity, and its further course can be followed upward and backward across the mediastinal surface as far as the lower part of the hilum.

- Impressions

There is a large and deep concavity called the cardiac impression, on the mediastinal surface to accommodate the pericardium. On the same surface, immediately above the hilum, is a well-marked curved furrow produced by the aortic arch, and running upward from this toward the apex is a groove accommodating the left subclavian artery; a slight impression in front of the latter and close to the margin of the lung lodges the left innominate vein.

Behind the hilum and pulmonary ligament is a vertical furrow produced by the descending aorta, and in front of this, near the base of the lung, the lower part of the esophagus causes a shallow impression.

Development

The development of the human lungs arise from the laryngotracheal groove and develop to maturity over several weeks inside the foetus and for several months following birth.[4] The larynx, trachea, bronchi and lungs begin to form during the fourth week of embryogenesis.[5] At this time, the lung bud appears ventrally to the caudal portion of the foregut. The location of the lung bud along the gut tube is directed by various signals from the surrounding mesenchyme, including fibroblast growth factors. At the same time as the lung bud grows, the future trachea separates from the foregut through the formation of tracheoesophageal ridges, which fuse to form the tracheoesophageal septum.

The lung bud divides into two, the right and left primary bronchial buds.[6] During the fifth week the right bud branches into three secondary bronchial buds and the left branches into two secondary bronchial buds. These give rise to the lobes of the lungs, three on the right and two on the left. Over the following week the secondary buds branch into tertiary buds, about ten on each side.[7] From the sixth week to the sixteenth week, the major elements of the lungs appear except the alveoli, which makes survival, if born, impossible.[8] From week 16 to week 26, the bronchi enlarge and lung tissue becomes highly vascularised. Bronchioles and alveolar ducts also develop. During the period covering the 26th week until birth the important blood-air barrier is established. Specialised alveolar cells where gas exchange will take place, together with the alveolar cells that secrete pulmonary surfactant appear. The surfactant reduces the surface tension at the air-alveolar surface which allows expansion of the terminal saccules. These saccules form at the end of the bronchioles and their appearance marks the point at which limited respiration would be possible.[9]

First breath

At birth, the baby's lungs are filled with fluid secreted by the lungs and are not inflated. When the newborn is expelled from the birth canal, its central nervous system reacts to the sudden change in temperature and environment. This triggers it to take the first breath, within about 10 seconds after delivery.[10] The newborn lung is far from being a miniaturized version of the adult lung. It has only about 20,000,000 to 50,000,000 alveoli or 6 to 15 percent of the full adult compliment. Although it was previously thought that alveolar formation could continue to the age of eight years and beyond, it is now accepted that the bulk of alveolar formation is concluded much earlier, probably before the age of two years. The newly formed inter alveolar septa still contain a double capillary network instead of the single one of the adult lungs. This means that the pulmonary capillary bed must be completely reorganized during and after alveolar formation, it has to mature. Only after full microvascular maturation, which is terminated sometime between the ages of two and five years, is the lung development completed and the lung can enter a phase of normal growth.[11]

Function

Respiration

The respiratory system's alveoli are the sites of gas exchange with blood.

- The sympathetic nervous system via noradrenaline acting on the beta receptors causes bronchodilation.

- The parasympathetic nervous system is through the vagus nerve,[12] via acetylcholine, which acts on the M-3 muscarinic receptors, maintains the resting tone of the bronchiolar smooth muscle. This action is related, although considered distinct from bronchoconstriction.

- Many other non-autonomic nervous and biochemical stimuli, including carbon dioxide and oxygen, are also involved in the regulation process.

There is also a relationship noted between the pressures in the lung, in the alveoli, in the arteries and in the veins. This is conceptualised into the lung being divided into three vertical regions called the zones of the lung.[13]

Respiratory system

The trachea divides at a junction–the carina of trachea, to give a right bronchus and a left bronchus, and this is usually at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra. The conducting zone contains the trachea, the bronchi, the bronchioles, and the terminal bronchioles.

The respiratory system contains the respiratory bronchioles, the alveolar ducts, and the alveoli.

The conducting zone and the respiratory components, except the alveoli, comprise the air passageways, with gas exchange only taking place in the alveoli of the respiratory system. The conducting zone is reinforced with cartilage in order to hold open the airways. Air is warmed to 37 °C (99 °F), humidified and cleansed by the conduction zone; particles from the air being removed by the cilia which are located on the walls of all the passageways. The lungs are surrounded and protected by the rib cage.

Volumes

Regarding lung volumes and lung capacities include inspiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, expiratory reserve volume, and residual volume.[14] The total lung capacity depends on the person's age, height, weight, sex, and normally ranges between 4,000 and 6,000 cm3 (4 to 6 L). For example, females tend to have a 20–25% lower capacity than males. Tall people tend to have a larger total lung capacity than shorter people. Smokers have a lower capacity than nonsmokers. Lung capacity is also affected by altitude. People who are born and live at sea level will have a smaller lung capacity than people who spend their lives at a high altitude. In addition to the total lung capacity, one also measures the tidal volume, the volume breathed in with an average breath, which is about 500 cm3.[15]

Lung function tests include spirometry, measuring the amount (volume) and/or speed (flow) of air that can be inhaled and exhaled.

Modification of substances

The lungs convert angiotensin I to angiotensin II. In addition, they remove several blood-borne substances, such as a few types of prostaglandins, leukotrienes, serotonin and bradykinin.[16]

Taste

In 2010, researchers found bitter taste receptors in lung tissue, which cause airways to relax when a bitter substance is encountered. They believe this mechanism is evolutionarily adaptive because it helps clear lung infections, but could also be exploited to treat asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[17]

Clinical significance

The lungs are prone to infectious diseases. Tuberculosis is a serious infectious disease of the lung as is bacterial pneumonia.

Pulmonary fibrosis is a condition that can prove fatal. The lung tissue is replaced by fibrous connective tissue which causes irreversible lung scarring.

Lung cancer can often be incurable. Also cancers in other parts of the body can be spread via the bloodstream and end up in the lungs where the malignant cells can metastasise.

A pulmonary embolism is a blood clot that becomes lodged in the lung.

See also

- This article uses anatomical terminology; for an overview, see anatomical terminology.

Additional images

-

Left lung

-

Diagram of the respiratory system

-

Anatomy of lungs

-

Front view of heart and lungs

-

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery

-

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum, seen from behind

-

The thymus of a full-time fetus, exposed in situ

-

Human right lung

-

Human embryo, 38 mm, 8–9 weeks.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Tomco, Rachel. "Lungs and Mechanics of Breathing". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- ↑ Notter, Robert H. (2000). Lung surfactants: basic science and clinical applications. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. p. 120. ISBN 0-8247-0401-0. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ medilexicon.com > Medical Dictionary - 'Parenchyma Of Lung' In turn citing: Stedman's Medical Dictionary. 2006

- ↑ Sadler T (2003). Langman's Medical Embryology (9th ed. ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-4310-9.

- ↑ Moore KL, Persaud TVN (2002). The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology (7th ed. ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-9412-8.

- ↑ Larsen WJ. Human Embryology 2001.Page 144

- ↑ Larsen WJ. Human Embryology 2001. Page 144

- ↑ Kyung Won, PhD. Chung (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 156. ISBN 0-7817-5309-0.

- ↑ Dorlands Medical Dictionary 2012 Page 1660

- ↑ About.com > Changes in the newborn at birth Review Date: 27 November 2007. Reviewed By: Deirdre OReilly, MD

- ↑ Burri, P (n.d). lungdevelopment. Retrieved March 21, 2012, from www.briticannica.com/EBchecked/topic/499530/human-respiration/66137/lung-development

- ↑ http://web.carteret.edu/keoughp/LFreshwater/PHARM/Blackboard/PNS/Neural%20Control%20of%20Lung%20Function.htm

- ↑ Permutt S, Bromberger-Barnea B, Bane H.N (1962). "Alveolar Pressure, Pulmonary Venous Pressure, and the Vascular Waterfall". Med. thorac. 19: 239–269. doi:10.1159/000192224.

- ↑ Weinberger SE (2004). Principles of Pulmonary Medicine (4th ed. ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-9548-5.

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ Walter F., PhD. Boron (2004). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3. Page 605

- ↑ Taste Receptors | University of Maryland Medical Center

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||