Hudson Stuck

Hudson Stuck (November 11, 1863 – October 10, 1920) was a British native who became an Episcopal priest, social reformer, and mountain climber in the United States. With Harry P. Karstens, he co-led the first expedition to successfully climb Mount McKinley (Denali) in June 1913, via the South Summit. He published five books about his years in Alaska. Two memoirs were issued in new editions in 1988, including his account of the ascent of Denali.

Stuck was born in London and graduated from King's College London. He immigrated to the United States in 1885 and lived there for the rest of his life. After working as a cowboy and teacher for several years in Texas, he went to University of the South to study theology. After graduation, he was ordained as an Episcopal priest. Moving to Alaska in 1904, he served as Archdeacon of the Yukon, acting as a missionary for the church and a proponent of "muscular Christianity". He died of pneumonia in Fort Yukon, Alaska.

Stuck and the naturalist John Muir are honored with a feast day on April 22 of the liturgical calendar of the US Episcopal Church.

Early life and education

Stuck was born in Paddington, London, England to James and Jane (Hudson) Stuck. He attended Westbourne Park Public School and King's College. Yearning for a bigger life, he immigrated to Texas in 1885, where he worked as a cowboy near Junction City. He also taught in one-room schools at Copperas Creek, San Angelo, and San Marcos.[1]

In 1889 he enrolled to study theology at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. After completing his studies, Stuck became an Episcopal priest in 1892. He first served a congregation in Cuero, Texas for two years.[1]

He was called to St. Matthew's Cathedral in Dallas in 1894. Two years later, he became dean. He stressed progressive goals in his sermons and regularly published articles related to his causes. There he founded a night school for millworkers, a home for indigent women, and St. Matthew's Children's Home. In 1903 he gained passage in Texas of the first state law against child labor.[1] He regularly preached and wrote against lynching.[1] It was at an all-time high in the South around the turn of the century, which was also the period when state legislatures were passing legislation and constitutions that disfranchised blacks and many poor whites.

Alaska mission

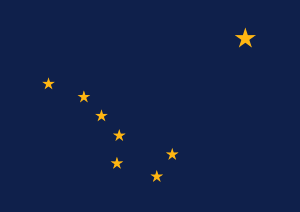

In 1904 Stuck moved to Alaska to serve with Missionary Bishop Peter Trimble Rowe. Under the title Archdeacon of the Yukon and the Arctic, with a territory of 250,000 square miles, Stuck traveled between the scattered parishes and missions by dogsled and boat as well as foot and snowshoe.[1] In his first year, Stuck established a church, mission and hospital at Fairbanks, the new boomtown filling up with miners and associated hangers on. Some staff came from Klondike, where the gold rush had ended. The small hospital treated epidemics of meningitis and typhoid fever, as well as pneumonia common in the North.[2]

In 1905, Rev. Charles E. Betticher, Jr joined Stuck in Alaska as a missionary. They founded numerous missions in the Tanana Valley over the next decade: at Nenana (St. Mark's Mission and Tortella School at Nenana, the school in 1907), St. Barnabas at Chena Native Village, St. Luke’s at Salcha, and St. Timothy’s at Tanacross (near Tok, formerly known as the Tanana Crossing). All served the Alaska Natives of the region.[2] Tortella School was the only boarding school to serve native children in the Interior of Alaska, and was supported by scholarships and offerings raised by the Episcopal Church. Missionary Anne Cragg Farthing ran the school and was the primary teacher. (Her brother was bishop of Toronto, Ontario.[2]

Five hundred miles up the Koyukuk River from its confluence with the Yukon, at its junction with its tributary the Alatna River, in 1907 Stuck founded a mission he called Allakaket (Koyukon for "at the mouth of the Alatna") but others called St. John's in the Woods for the several hundred Indians here.[2] For years Episcopal woman missionaries ran the remote station just above the Arctic Circle, includung Deaconess Clara M. Carter and Clara Heinz. (Other women missionaries later included Harriet Bedell who, like Stuck, has been honored on the Episcopal liturgical calendar.) The mission served both Koyukon and Iñupiat, who were settled on opposite sides of the river. The latter had come up the Kobuk River from lower areas. Thus the missioners had two Native languages to learn.[2]

To reach the scattered populations of miners and other frontiersmen, Stuck started the Church Periodical Club. Based in Fairbanks, it collected and distributed periodicals to all the missions and to other settlements where Americans gathered. It did not have only church literature, and in some locations, it provided almost the only reading material around.[2]

Stuck traveled each winter more than 1500–2000 miles by dogsled to visit the missions and villages. In 1908, he acquired the launch called The Pelican, a shallow riverboat. He used it on the Yukon River and tributaries to visit the Athabascans in their summer camps, where they fished and hunted. He reported that in twelve seasons' cruises, ranging from i,800 to 5,200 miles each summer, he traveled a total of up to 30,000 miles along the rivers.[2]

Stuck wrote and published five books, memoirs of his times in Alaska, in part to reveal the exploitation of the Alaska Native peoples that he witnessed in his work.

Stuck had experience mountain climbing, including having ascended Mount Rainier in Washington state.

Ascent of McKinley

Stuck recruited Harry Karstens, a respected guide, to join his expedition. Other members were Walter Harper and Robert G. Tatum, both 21, and two student volunteers from the mission school, Johnny Fred (John Fredson), and Esaias George. They departed from Nenana on March 17, 1913. They reached the summit of McKinley on June 7, 1913. Harper, of mixed Alaska Native and Scots descent, reached the summit first. Fredson, then 14, acted as their base camp manager, hunting caribou and Dall sheep to keep them supplied with food.[3]

The party made atmospheric measurements at the peak of the mountain for purposes of determining its elevation. At the summit, their aneroid barometer read 13.175 inches, their boiling-point thermometer read 174.9 degrees, their mercurial barometer read 13.617 inches. The alcohol minimum recording thermometer read 7 °F. These measurements, with others taken at Fort Gibbon and Valdez, were reduced by C. E. Griffin, Topographic Engineer of the United States Geological Survey, to produce an elevation for Denali of 20,384 feet. The figure quoted by the National Park Service in 2005 is 20,320 feet.

"The tent-pole was used for a moment as a flagstaff while Tatum hoisted a little United States flag he had patiently and skillfully constructed in our camps below out of two silk handkerchiefs and the cover of a sewing-bag. The pole was put to its permanent use. It had already been carved with a suitable inscription, and now a transverse piece, already prepared and fitted, was lashed securely to it and it was planted on one of the little snow turrets of the summit - the sign of our redemption, high above North America." (from Ascent of Denali, page 105)

They also erected a six-foot high cross at the summit.[3]

When the party returned to base camp, Stuck sent a messenger to Fairbanks to announce their success in reaching the peak of the mountain. His achievement was announced on June 21, 1913 by the New York Times and carried nationally.[3]

Stuck was scheduled to go to New York City in October for a General Convention of the Episcopal Church.[3] This gave him another opportunity to talk about the ascent.

Later life

Several of the mission churches established by the Episcopal Church in remote areas of the Interior during the early 20th century have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Stuck continued to urge Alaska Native youths in their education, helping arrange scholarships and sponsors for education in the Lower 48. For instance, John Fredson was the first Alaska Native to finish high school and graduate from college. Sponsored by Stuck and the Episcopal Church, he went to the University of the South in Tennessee. After returning to Alaska, he developed as a Gwich'in leader. In 1941 he gained federal recognition of the Venetie Indian Reserve to protect his people's traditional territory. Walter Harper was accepted at medical school in Philadelphia, but died en route when his ship sank off the coast of Alaska.

Stuck worked as a priest in Alaska for the rest of his life, serving both Alaska Natives and American settlers. Like many other missionaries, he never married. He died of pneumonia in Fort Yukon. By his request, he was buried in the native cemetery there.

Legacy and honors

- A memorial service was conducted at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City in his honor.

- He is celebrated (along with John Muir on April 22) with a feast day on the Episcopal calendar as a modern saint.

Books

- Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled. Charles Scribner's Sons. 1914. [reprinted by Prescott, Arizona: Wolfe Publishing Co., Inc., 1988. ISBN 0-935632-66-2].

- Voyages on the Yukon and its Tributaries, 1917

- The Ascent of Denali, The 1913 Expedition that First Conquered Mt. McKinley. (reprinted by) Prescott, Arizona: Wolfe Publishing Co., Inc. 1918/1988. ISBN 0-935632-69-7. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

See also

- Harriet Bedell, Episcopal missionary in Alaska, also honored on liturgical calendar

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Hudson Stuck", Texas State Handbook Online

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Hudson Stuck, D.D. Archdeacon of the Yukon, "The Alaskan Missions of the Episcopal Church", New York: Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society, 1920, at Project Canterbury website

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Dr. Stuck scales Mount M'Kinley" (PDF). The New York Times. June 21, 1913. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

Further reading

- David Dean, Breaking Trail: Hudson Stuck of Texas and Alaska (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1988).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hudson Stuck. |

- Works by Hudson Stuck at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hudson Stuck at Internet Archive

- Hudson Stuck, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled, 1914, Internet Archive

- Hudson Stuck, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled, 1916, Project Gutenberg

- Hudson Stuck, Voyages on the Yukon and its Tributaries, 1917 (available through google books and hathitrust.org)

- Hudson Stuck, The Ascent of Denali (Mount McKinley), 1918, Project Gutenberg

- Hudson Stuck, Baccaulaureate Sermon Given at Columbia University, 1916 (available through google books)

- David M. Dean, "Hudson Stuck biography - Texas State Historical Association

|