Hua–Yi distinction

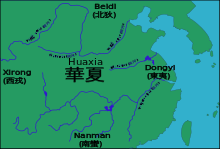

華夷之辨, the distinction between Hua (華) and Yi (夷), also known as Sino-barbarian dichotomy,[1] is an ancient Chinese conception that differentiated a culturally defined "China" (called Hua, Huaxia 華夏, or Xia 夏) from cultural or ethnic outsiders (Yi "barbarians"). Although Yi is often translated as "barbarian," there are also other ways of translating this term into English. Some of the examples include “foreigners,”[2]"ordinary others,”[3] “wild tribes,”[4] “uncivilized tribes,”[5] and so forth.

The Hua–Yi distinction was basically cultural, but it could also take ethnic or racist overtones (especially in times of war). In its cultural form, the Hua–Yi distinction assumed Chinese cultural superiority, but also implied that outsiders could become Hua by adopting Chinese values and customs. When this "cultural universalism"[6] took a more racial guise, however, it could have harmful effects.[7]

Historical context

Ancient China was a group of states that arose in the Yellow River valley, one of the earliest centers of human civilization. According to historian Li Feng, in the Western Zhou (ca. 1041–771 BCE) the contrast between the "Chinese" Zhou and the "Rong" or "Yi" was "more political than cultural or ethnic."[8] Lothar von Falkenhausen argues that the perceived contrast between "Chinese" and "Barbarians" was accentuated during the Eastern Zhou period (770–256 BCE), when adherence to Zhou rituals was increasingly recognized as a "barometer of civilization."[9] Gideon Shelach also agrees that this distinction, which was "based on shared cultural values", emerged during the Zhou period.[10]

Shelach, however, claims that Chinese texts tended to overstate the distinction and to ignore similarities between the Chinese and their northern neighbors.[11] Nicola di Cosmo also doubts the existence of a strong demarcation between a "Zhou universe and a discrete, 'barbarian,' non-Zhou universe" at the time.[12] He traces this conception to Sima Qian's "assumption (or the pretense of it) that a chasm had always existed between China – the Hua-Hsia [Huaxia] people – and the various alien groups inhabiting the north."[13]

At the conclusion of the Warring States period the first unified Chinese state was established by the Qin Dynasty in 221 BCE, the office of the Emperor was set up and the Chinese script was forcibly standardized. The subsequent Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) created a Han cultural identity among its populace that would last to the present day.[14]

The Han Chinese civilization has had a dominant influence on neighboring states such as Korea, Japan, Vietnam and Thailand, plus many other South East Asian countries. Although only sporadically enforced with military might, the Sinocentric system treated these countries as vassals of Emperor being the Son of Heaven (Chinese:天子), who has the Mandate of Heaven (Chinese:天命). Areas outside the Sinocentric influence were considered under this concept to consist of uncivilized lands inhabited by barbarians, or Huawaizhidi.[15]

Throughout history, the frontiers of China were periodically attacked by nomadic tribes from the north and west. In ancient times, these nomadic tribal people were considered to be barbarians when compared to the people of the Central Plain (中原), who had begun to build cities and live an urban life based on agriculture. It was consideration of how best to deal with this threat that led Confucius (551 – 479 BCE) to formulate principles for relationships with the barbarians, briefly recorded in two of his Analects.[16]

It was not until the explosion of European trade and colonialism in the 18th and 19th centuries that Chinese civilization become fully exposed to cultural and technological developments that had outstripped China, and was forced to painfully modify its traditional views of its relationship with the "barbarians."[17]

China

The great Chinese philosopher Confucius lived during a time of warfare between the Chinese states. He regarded peoples who did not respect "li", or ritual propriety, as barbarians since the workings of a state should be founded on ethical conduct rather than imposed by princes. In the Ames and Rosemont translation of Analect 3.5, Confucius said: "The Yi and Di barbarian tribes with rulers are not as viable as the various Chinese states without them."[18] This is often interpreted as meaning that the Chinese culture is superior to the barbarian culture even in times of anarchy. However, the classic translation by James Legge is ambiguous: "The rude tribes of the east and north have their princes, and are not like the States of our great land which are without them."[19]

The Disposition of Error, a fifth-century tract defending Buddhism, a religion that had originated outside the Sinocentric sphere in India, notes that when Confucius was threatening to take residence among the nine barbarian nations (九黎) he said, "If a gentleman-scholar dwells in their midst, what baseness can there be among them?"'[20] An alternate translation of Analect 9.14 is "Someone said: 'They are vulgar. What can you do about them?' The Master said: 'A gentleman used to live there. How could they be vulgar?'"[21] In either translation, there is a clear implication that Hua culture is superior.

On the other hand, the prominent Shuowen Jiezi character dictionary (121 CE) defines yi 夷 as 平 "level; peaceful" or 東方之人 "people of eastern regions", and first records that this Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) regular script 夷 and the Qin Dynasty (221-207 BCE) seal script for shi incorporate both the 大 "big" and 弓 "bow" radicals. The Shuowen also indicates that the radical “big” in the character yi means human.

Zhou Dynasty

The Bamboo Annals recorded that the founder of Zhou, King Wu of Zhou "led the lords of the western barbarians" to conquer the Shang Dynasty.[22] While the Duke Huan of Qi once called on the various Chinese states to fight against the barbarians and uphold the King of Zhou then amongst themselves (Chinese:尊王攘夷).[23]

Mencius believed that Confucian practices were universal and timeless, and thus followed by both Hua and Yi, "Shun was an Eastern barbarian; he was born in Chu Feng, moved to Fu Hsia, and died in Ming T'iao. King Wen was a Western barbarian; he was born in Ch'i Chou and died in Pi Ying. Their native places were over a thousand li apart, and there were a thousand years between them. Yet when they had their way in the Central Kingdoms, their actions matched like the two halves of a tally. The standards of the two sages, one earlier and one later, were identical."[24]

Jin Dynasty

In order to alleviate the shortages of labor caused by the Three Kingdoms wars, the Jin let millions of non-Chinese people move into Jin territory. However, many officials opposed this decision in the name of the Hua–Yi distinction, claiming that if the barbarians did not identify with the Huaxia, they would conspire to destroy the Chinese empire.[25]

Wu Hu uprising

During the Wu Hu (五胡) uprising and ravaging of north China that occurred around 310CE, the Jin dynasty and other Chinese used the Hua–Yi distinction to call on the population to resist the Wu Hu.[26] The historians of the southern dynasties, who were all Han Chinese, depicted the Wu Hu as barbaric and different from the Chinese.[27]

Ran Min's order to kill the barbarians

In either 349 or 350CE, the Han Chinese general Ran Min (冉閔) seized power from the last emperor of the Later Zhao and encouraged Han Chinese to slaughter Jie people, a large number of which were living in the Zhao capital, Ye. In this massacre and the wars that ensued, hundreds of thousands of Jie (羯), Qiang (羌), and Xiongnu (匈奴) men, women, and children were killed. The Wu Hu quickly unified to fight Ran Min, but Ran Min won victory after victory. Despite this military success, however, Ran's regime was toppled in 353 CE. As a result of this turmoil, three of the five main "barbarian" ethnic groups in China disappeared from Chinese history.[28]

Ran Min continues to be a controversial figure. He is considered by some to be a hero, whereas others believe he is an example of the extreme prejudice that can result from the concept of "Hua-Yi distinction".[28]

Northern Wei

Emperor Shaowu of Northern Wei (a state that controlled the north of China), who was a Xianbei (鮮卑), attempted to eliminate Hua-Yi zhi bian in his state by forcing the Xianbei to sinocize and adopt Han Chinese ways. The Xianbei language was outlawed and Xianbei people began to adopt Chinese surnames ; for example, the Tuobas became the Yuans.[29]

Sui Dynasty

In 581, the Sui Emperor Yang Jian deposed the Xianbei ruler of Northern Zhou and restored the rule of the Han Chinese over North China. This event marked the end of all power that the Xianbei and other non-Chinese groups had over China, and racial tension subsided.[30]

Tang Dynasty

Tang Dynasty was regarded as one of the Golden Ages of Chinese history, as well as one of the most cosmopolitan regimes in China's past. The Tang was one of the peaks of the Chinese Empire's military strength, political unity, economic influence, and cultural efflorescence. During Tang's time Tibetans, Southeast Asians, Persians, Arabs, Jews, Japanese, Koreans, Turks and Indians all came to Chang'an and other Tang cities to do business or study. Apart from bringing different cultures of the world into Tang Dynasty, these people brought Buddhism, Islam, Zarathustrian (Xianjiao 祆教), Persian Manichean thought (Monijiao 摩尼教) and Syriac Christianity (Jingjiao 景教), which all began to take root and flourish in China.[31]

This cosmopolitan policy caused some controversy among the literati, who questioned the governor of Kaifeng's recommendation of the Arab Li Yansheng (李彥昇) to take an imperial examination in 847. The Tang intellectual Chen An (陳黯) wrote an essay defending the decision, "The Heart of Being Hua" (Chinese: 華心; pinyin: Huá xīn), which is cited as expressing the "classic non-xenophobic" Chinese position on the Hua–Yi distinction. In the essay, Chen writes: "If one speaks in terms of geography, then there are Hua and Yi. But if one speaks in terms of education, then there can be no such difference. For the distinction between Hua and Yi rests in the heart and is determined by their different inclinations."[32]

The prominent Tang Confucian Han Yu wrote in his essay Yuan Dao the following: "When Confucius wrote the Chunqiu, he said that if the feudal lords use Yi ritual, then they should be called Yi; If they use Chinese rituals, then they should be called Chinese." Han Yu went on to lament in the same essay that the Chinese of his time might all become Yi because the Tang court wanted to put Yi laws above the teachings of the former kings.[33] Therefore, Han Yu's essay shows the possibility that the Chinese can lose their culture and become the uncivilized outsiders, and that the uncivilized outsiders have the potential to become Chinese.

Arguments which excoriate the Tang's lax attitude towards foreigners were strengthened after the Yi-led An Lushan Rebellion (755–763), which propelled the Tang into terminal decline.[34] An intellectual movement "to return to the pure... sources of orthodox thought and morality", such as the Classical Prose Movement, also targeted "foreign" religions, as in Han Yu's diatribe against Buddhism. Emperor Wenzong of Tang passed decrees in line with this zeitgeist, especially restricting Iranian religions and Southeast Asians, but this policy was relaxed by his successors.[35]

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

The "Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms" was a period in which the north of China was ruled by a non-Chinese people, the Shatuo, for three short-lived dynasties and the south ruled by Chinese. Their legitimacy was recognized by the Song Dynasty.[36]

Song Dynasty

The Chinese Song Dynasty saw both an economic boom and non-Chinese states, such as the Liao, intruding on China's territory. As states such as the Khitan Liao and Tangut Xi Xia took over territories inhabited by large numbers of Chinese, they too asserted that they were Chinese and successors to the Tang Dynasty. The Song also had to deal with legitimacy issues that several of the northern states that the Song state were continued from were ruled by Shatuo, who were non-Chinese.

Song scholars asserted two notions: firstly, they argued that groups like the Shatuo, who largely continued the rule of the Tang, were not "barbarian" but Chinese, so that the Song were descended from dynasties that were "Hua" or Chinese. Secondly, the Song asserted that the Liao (遼) and Xi Xia (西夏), and later the Jin (金), were barbarian states despite their control of large areas of Chinese territory, because they had not inherited any mandate from a legitimate dynasty that was "Hua" and not "Yi."[37]

Yuan Dynasty

This conflict over the legitimacy of the Song-era states rose up again in the Yuan dynasty, as the rulers were non-Han-Chinese themselves. The Yuan dynasty took a different view than the Song. The Yuan argued that the Song, Liao and Jin were all legitimate; therefore all three dynasties were given their own history, as recognition of their legitimacy.

The Yuan engaged in racial segregation and divided society into four categories:

- Mongols (蒙古): who were at the top.

- Semu (色目; "assorted categories"): a term for non-Chinese and non-Mongol foreigners who occupied the second slate;

- Han (漢人): a term for the Han Chinese, Jurchens, and Khitan under the rule of the Jin dynasty;

- Southerner (南人): a term for Han Chinese under the rule of the Song dynasty.

In addition, the Yuan also divided society into 10 castes, based on "desirability":[38]

- High officials (Chinese: 大官)

- Minor officials (Chinese: 小官)

- Buddhist monks (Chinese: 釋)

- Daoist priests (Chinese: 道)

- Physicians (Chinese: 医)

- Peasants (Chinese: 農)

- Hunters (Chinese: 獵)

- Courtesans (Chinese: 妓)

- Confucian scholars (Chinese: 儒)

- Beggars (Chinese: 丐)

Mongol rule, viewed as barbaric and humiliating for the Chinese,[39] did not last long in China (from 1271 to 1368).

On the other hand, according to Fudan University historian Yao Dali, even the supposedly "patriotic" hero Wen Tianxiang of the late Song and early Yuan period did not believe the Mongol rule to be illegitimate. In fact, Wen was willing to live under Mongol rule as long as he was not forced to be a Yuan dynasty official, out of his loyalty to the Song dynasty. Yao explains that Wen chose to die in the end because he was forced to become a Yuan official. So, Wen chose death due to his loyalty to his dynasty, not because he viewed the Yuan court as a non-Chinese, illegitimate regime and therefore refused to live under their rule. Yao also says that many Chinese who were living in the Yuan-Ming transition period also shared Wen's beliefs of identifying with and putting loyalty towards one's dynasty above racial/ethnic differences. Many Han Chinese writers did not celebrate the collapse of the Mongols and the return of the Han Chinese rule in the form of the Ming dynasty government at that time. Many Han Chinese actually chose not to serve in the new Ming court at all due to their loyalty to the Yuan. Some Han Chinese also committed suicide on behalf of the Mongols as a proof of their loyalty.[40] These things show that many times, pre-modern Chinese did view culture (and sometimes politics) rather than race and ethnicity as the dividing line between the Chinese and the non-Chinese. In many cases, the non-Chinese could and did become the Chinese and vice versa, especially when there was a change in culture.

Ming Dynasty

In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang proclaimed the Ming Dynasty and issued a long manifesto, in which he accused the Mongols of being barbarians who had usurped the Chinese thrones, and who had committed atrocities such as rape and massacre. He lists incidents where the Mongols massacred men in entire villages and entitled themselves to the women. His Northern expedition was quickly successful; Beijing was captured in the same year and China was again governed by Han Chinese.[41]

Although the Ming referred to the preceding Yuan as "胡元", or barbarian Yuan, they also accepted the Yuan before them as a legitimate dynasty. In fact, in contrast to what was said in the previous paragraph, Zhu Yuanzhang also indicated on another occasion that he was happy to be born in the Yuan period and that the Yuan did legitimately receive the Mandate of Heaven to rule over China. In addition, one of his key advisors, Liu Ji, generally supported the idea that while the Chinese and the non-Chinese are different, they are actually equal. Liu was therefore arguing against the idea that Hua was and is superior to Yi.[42]

During the Miao Rebellions (Ming Dynasty), the Ming dynasty forces engaged in massive slaughter of Miao people and other native ethnic groups to southern China, after castrating Miao boys to use as eunuch slaves, Chinese soldiers took Miao women as wives and colonized the southern provinces.[43][44][45][46]

Towards the end of the Ming dynasty, Ming dynasty loyalists invoked Hua-Yi zhi bian to urge the Chinese to resist the Manchu invaders.[47]

Qing dynasty

The Qing's order that all subjects of the Qing shave their forehead and braid the rest of their hair into a queue was viewed as a symbolic gesture of servitude by many Han Chinese, who thought that changing their dress to the same as Yi would be contrary to the spirit of "Hua-Yi zhi bian."

Scholar Lü Liuliang (1629–1683), who lived through the transition between the Ming and the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, refused to serve the new dynasty because he claimed that upholding the difference between Huaxia and the Yi was more important than respecting the righteous bond between minister (臣) and sovereign (君王).[48] In 1728, a failed examination candidate called Zeng Jing (曾靜), who had been influenced by Lü's works, called for the overthrow of the Manchu regime.[48] The Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723–1735), whom Zeng had accused of ten major crimes, took this event as an opportunity to educate the Qing's Chinese subjects. In a series of discussions with Zeng Jing that historian Jonathan Spence recounts in Treason by the Book, the emperor proclaimed that the Chinese were not inherently superior to the barbarians. To justify his statements, he declared that King Wen, the sage king and the founder of the Zhou dynasty, was a person of Western Yi origin, but this did not hurt King Wen's greatness. The Yongzheng Emperor also borrowed from Han Yu, indicating that Yi can become Hua and vice versa. In addition, according to Yongzheng, both Hua and Yi were now a part of the same family under the Qing. One of the goals of the tract Dayi juemi lu (大義覺迷錄), which the Yongzheng Emperor published and distributed throughout the empire in 1730, was "to undermine the credibility of the hua/yi distinction."[48] However, due to the fact that this tract also helped to expose many unsavory aspects of court life and political intrigues in the imperial government, Yongzheng’s successor the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736–1796) recalled the tracts and had them burned for the fear that it would undermine the legitimacy of the Qing empire.

During the Qing, the Qing destroyed writings that criticized the Liao, Jin and Yuan out of the Hua–Yi distinction.

The leaders of the Taiping rebellion issued a long proclamation based on Zhu Yuanzhang's denuciation of the Mongols and accused the Manchu of similar crimes. A popular slogan for rebellion in the Qing was "Overthrow the Qing, revive the Ming" (反清復明).

Sun Yat-sen also used the Hua–Yi distinction to justify the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.[30]

However, it is also true that during the Qing Dynasty, the rulers of China adopted Confucian philosophy and Han Chinese institutions to show that the Manchu rulers had received the Mandate of Heaven to rule China, while at the same time trying to retain their own indigenous culture.[49] Due to the Manchus' adoption of Han Chinese culture, most Han Chinese (though not all) did accept the Manchus as the legitimate rulers of China.

Republic of China

The historian Frank Dikötter (1990:420) says the Chinese "idea of 'race' (zhong [種], "seed," "species," "race") started to dominate the intellectual scene" in the late 19th-century Qing dynasty and completed the "transition from cultural exclusiveness to racial exclusiveness in modern China" in the 1920s.[50]

Following the overthrow of the Qing, rumors have it that Sun Yat-sen went to the grave of Zhu Yuanzhang and told him that the Huaxia had been restored and the barbarians overthrown. However, after the ROC revolution, Sun also advocated that all ethnic groups in China are now a part of the same ethnic Chinese family.

People's Republic of China

The PRC did not abide by the concept of "Hua Yi zhi bian" and recognized the Qing and Yuan as legitimate dynasties. Initially, the CPC condemned all Chinese dynasties as "Feudal oppressors".

Hua-Yi zhi bian is only an intellectual issue in academic discussions these days. It also has very little practical and real significance. In fact, both of these things have been true since the founding of the ROC till the present day.[51]

Conceptualization of the Hua–Yi distinction in non-Chinese states

Japan

|

In the second unsuccessful Mongol invasion of Japan in 1281 CE, 20–30,000 prisoners were taken but only 10,000 Southern Song Chinese were spared.[52] The Japanese separated the Song troops who had recently surrendered to the Mongols from the other prisoners, called them "Men of Tang", and enslaved them. On the other hand, the Northern Han Chinese, Khitan, Jur'chens, Koreans, and Mongols who had been living in the Mongol Empire for a century, were executed.

Korea

|

After the Manchus conquered Ming Dynasty in 1644 and established the Qing Dynasty, the Joseon Koreans often called themselves "Sojunghwa" which, translates into "Lesser China". They showed solidarity and thoughtfulness to the citizens of Ming, rather than their now new rulers of the Qing dynasty through this stance. As Korea is often closely linked to previous Han Chinese civilizations and dynasties through writing and other cultural understandings, the concept of the "barbarians" now ruling China was a strong issue. This was especially as the foreign relations between the two countries were extremely close throughout history. These acts of closeness and understanding were shown throughout the Ming Dynasty in various involvements.

As the Ming dynasty came to be overthrown by the Manchus, Korea itself was worried of similar invasions and its own security from threats. This was due to previous instances in which Ming Chinese primarily aided Korea's independence such as in the Imjin Wars.[53] Long after the establishment of the Qing dynasty, the Joseon ruling elite and even the Joseon government continued to use the Chongzhen era name (Chinese:崇祯年号, ja:崇禎紀元) of the last Ming emperor.[54] Continually in secret, they referred to the Manchu Emperor as the "barbarian ruler" and Qing ambassadors as "barbarian ambassadors".[55] Korean feelings diplomatically, about the Manchu, could not be expressed as the "Barbarians" essentially held great power over Korea following their successful attacks and invasions in the Manchu campaigns of 1627 and 1637.

Its once great ally within the Ming dynasty was no more and acquiescence to the power of Qing and essentially the Barbarians, had to be shown in its governance. In the future, the Qing government, with its Manchu leadership, would assert more power over Korea and influence its policies. This would eventually lead Korea into becoming a Hermit Kingdom. This was to prevent foreign influence in a land the Qing government viewed as close to home and to assert Chinese authority, which was under threat from the western powers especially as a result of the unequal treaties signed following the First and Second Opium Wars.

Ryūkyū

|

The Ryūkyū Kingdom was heavily influenced by Chinese culture, taking language, architecture, and court practices from China.[56] It also payed annual tribute to first the Ming and later Qing courts from 1374 until 1874.

Vietnam

After the 18th century, after the devastating Tay Son wars, The ruling Nguyen dynasty consolidated its power by adopting a more radical Confucian worldview, With its territory expanded to its largest extend, the country came to clash with the Khmer and Lao kingdoms and various tribes on the Tay Nguyen highlands such as the Jarai and the Ma. In 1805, the Emperor Gia Long referred to Vietnam as trung quốc, the "middle kingdom".[57] In 1811, Gia Long proposed a law "Hán di hữu hạn", which means "making clear the border between the Vietnamese and barbarians", referring to the Vietnamese as Han people.[58] Cambodia was regularly called Cao Man, the country of "upper barbarians". In fact, earlier dynasties also considered themselves "Hua", in the sense that their nation was civilized, and their kingdom as a polity was at the center of Earth and Heaven. Even with regard to China Proper, Vietnamese dynasties claimed to be the Middle Kingdom while Chinese were "outsiders".[59]

External influences

Christianity

At the end of the 1813, Robert Morrison's translated Bible was published in Malacca (in what is now Malaysia); it is believed to be the world's first published Bible in the Chinese language. The same version was reputed to have been used by the Taiping Rebellion's leader Hong Xiuquan, who eventually used ideas borrowed from the Chinese Bible and staged a massive anti-Manchu military campaign originating in racial hatred.

Hong Xiuquan studied Christianity under Morrison for two months, but Morrison refused to baptize Hong. Not satisfied by calling Manchus barbarians as commonly implied in Hua-Yi zibian debate, Hong went one step further by calling the Manchus devil, as in the term anti-Christ in the Bible, at the same time he made claim that he was the brother of Christ, and so another Son of God.

See also

- Barbarian

- Foreign relations of Imperial China

- Graphic pejoratives in written Chinese

- Greater China

- List of recipients of tribute from China

- List of tributaries of Imperial China

- Suzerainty

- Tributary state

- Wang Fuzhi

Notes

- ↑ Pines (2003).

- ↑ Robert Morrison, The Dictionary of the Chinese Language, 3 vols. (Macao: East India Company Press, 1815), 1:61 and 586–587.

- ↑ Liu Xiaoyuan (2004), 10–11. Liu believes the Chinese in early China did not originally think of Yi as a derogatory term.

- ↑ James Legge, Shangshu, “Tribute of Yu” http://ctext.org/shang-shu/tribute-of-yu

- ↑ Victor Mair, Wandering on the way : early Taoist tales and parables of Chuang Tzu (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998),315.

- ↑ Dikotter (1994), 3.

- ↑ Terrill (2003), 41.

- ↑ Li, 286. Li explains that "Rong" meant something like "warlike foreigners" and "Yi" was close to "foreign conquerables."

- ↑ von Falkenhausen (1999), 544.

- ↑ Shelach (1999), 222–23.

- ↑ Shelach (1999), 222.

- ↑ Di Cosmo (2002), 103.

- ↑ Di Cosmo (2002), 2.

- ↑ Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais (2006), ###.

- ↑ Arrighi (1996), ###.

- ↑ Chin (2007), ###.

- ↑ Ankerl (2000), ###.

- ↑ Ames and Rosemont (1999), ###.

- ↑ "Confucius – The Analects Book 3" University of Adelaide. Retrieved 11 Jan 2009.

- ↑ "The Disposition of Error (c. 5th Century BCE)" City University of New York. Retrieved 11 Jan 2009

- ↑ Huang (1997), ###.

- ↑ Herrlee G. Creel, The Origins of Statecraft in China(Chicago:The University of Chicago Press, 1970),59.

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, page 116, 2001

- ↑ Mencius,D.C Lau tran. (Middlesex:Penguin Books, 1970),128.

- ↑ Li and Zheng 2001, 381.

- ↑ Li and Zheng 2001, 387–389.

- ↑ Li and Zheng 2001, 393–401.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Li and Zheng 2001, 401.

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, page 456-458, 2001

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, 2001

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, 2001, page 679-687

- ↑ Benite, Zvi Ben-Dor (2005). The Dao of Muhammad: A Cultural History of Muslims in Late Imperial China. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 1–3.

- ↑ http://www.confucianism.com.cn/detail.asp?id=25097 "孔子之作春秋也,诸侯用夷礼,则夷之;进于中国,则中国之."

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, page 679-687, 2001.

- ↑ A History of Chinese Civilization, Jacques Gernet, Pages 294–295

- ↑ Li Bo and Zheng Yin (2001), pg 778–788.

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history",ISBN 7-204-04420-7, pg 823–826, 2001.

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, page 920-921, 2001

- ↑ Li Bo, Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, page 920-927, 2001

- ↑ http://history.news.163.com/special/00013PNN/vol13.html.

- ↑ Li Bo and Zheng Yin (2001), 920–924.

- ↑ Zhou Songfang, "Lun Liu Ji de Yimin Xintai" (On Liu Ji's Mentality as a Dweller of Subjugated Empire) in Xueshu Yanjiu no.4 (2005), 112–117.

- ↑ Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1996). The eunuchs in the Ming dynasty. SUNY Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-7914-2687-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Louisa Schein (2000). Minority rules: the Miao and the feminine in China's cultural politics. Duke University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-8223-2444-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Frederick W. Mote, Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank (1988). The Cambridge history of China: The Ming dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 380. ISBN 0-521-24332-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ John Stewart Bowman (2000). Columbia chronologies of Asian history and culture. Columbia University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-231-11004-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Li Bo and Zheng Yin (2001), 1018–1032

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Lydia Liu (2004), 84. Lü's original sentence was "Hua yi zhi fen da yu jun chen zhi yi" 華夷之分,大於君臣之義.

- ↑ John King Fairbank, China: A New History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 146–149.

- ↑ Dikötter (1990), 420.

- ↑ Li Bo and Zheng Yin (2001), ###.

- ↑ "Khubilai Khan and Yuan Dynasty (AD 1261–1368)" republicanchina.org. Retrieved 11Jan 2009

- ↑ http://koreanhistoryproject.org/Ket/C12/E1204.htm |Paragraph 13

- ↑ Haboush (2005), 131–32.

- ↑ "In Chinese:朝鲜皇室的"反清复明"计划:为报援朝抗日之恩". ido.3mt.com.cn. 2009-01-24. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ↑ Kerr, George H. Okinawa: History of an Island People. 1957.

- ↑ Vietnam and the Chinese Model, Alexander Barton Woodside, Council on East Asian Studies Harvard, Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London 1988: P18

- ↑ Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mang (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response, Choi Byung Wook , Cornell University Southeast Asia Program Publications 2004: P136

- ↑ Ngàn Năm Aó Mũ, Trần Quang Đức, Nhã Nam Publishing House 2013: P25

References

- Ames, Roger T., and Henry Rosemont, Jr. (1999). Translated With an Introduction. The Analects of Confucius: A Philosophical Translation. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-43407-2, ISBN 978-0-345-43407-4.

- Ankerl, G. C. (2000). Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Arrighi, Giovanni (1996). "The Rise of East Asia and the Withering Away of the Interstate System." Journal of World-Systems Research, Volume 2, Number 15: 1–35.

- Chin, Annping (2007). The Authentic Confucius: A Life of Thought and Politics. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-4618-7, ISBN 978-0-7432-4618-7.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 369 p. ISBN 0-521-77064-5, ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- Dikötter, Frank (1990). "Group Definition and the Idea of 'Race' in Modern China (1793-1949)." Ethnic and Racial Studies 13:3, 420-432.

- Dikötter, Frank (1994). The Discourse of Race in Modern China. Stanford University Press.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Anne Walthall; James B. Palais (2005). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-13384-4, ISBN 978-0-618-13384-0.

- Farmer, Edward (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10391-0, ISBN 978-90-04-10391-7.

- Haboush, JaHyun Kim (2005). "Contesting Chinese Time, Nationalizing Temporal Space: Temporal Inscription in Late Choson Korea." In Lynn Struve (ed.), Time, Temporality, and Imperial Transition, pp. 115–41. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2827-5, ISBN 978-0-8248-2827-1.

- Huang, Chichung (1997). The Analects of Confucius (Lun yu). A Literal Translation with an Introduction and Notes. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506157-8, ISBN 978-0-19-506157-4.

- Li Bo and Zheng Yin, "5000 years of Chinese history", Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp, ISBN 7-204-04420-7, 2001.

- Li, Feng (2006). Landscape and Power in Early China: The Crisis and Fall of the Western Zhou, 1045–771 BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85272-2, ISBN 978-0-521-85272-2.

- Liu, Lydia (2004). The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01307-7, ISBN 978-0-674-01307-0.

- Liu, Xiaoyuan (2004). Frontier Passages: Ethnopolitics and the Rise of Chinese Communism, 1921–1945. Stanford: Stanford University Press. UNSW Press. 248 p. ISBN 0-86840-758-5, ISBN 978-0-86840-758-6.

- Pines, Yuri (2005). "Beasts or humans: Pre-Imperial origins of Sino-Barbarian Dichotomy", in Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian nomads and the sedentary world, eds. R. Amitai and M. Biran, pp. 59–102. Brill.

- Rowe, William T. (2007). Crimson Rain: Seven Centuries of Violence in a Chinese County. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5496-9, ISBN 978-0-8047-5496-5.

- Shelach, Gideon (1999). Leadership Strategies, Economic Activity, and Interregional Interaction: Social Complexity in Northeast China. Springer. ISBN 0-306-46090-4, ISBN 978-0-306-46090-6

- Shin, Leo K. (2006). The Making of the Chinese State: Ethnicity and Expansion on the Ming Borderlands. Cambridge University Press. 246 p. ISBN 0-521-85354-0, ISBN 978-0-521-85354-5.

- Terrill, Ross (2003). The New Chinese Empire: And What it Means for the World. UNSW Press. 288 p. ISBN 0-86840-758-5, ISBN 978-0-86840-758-6.

- von Falkenhausen, Lothar. "The Waning of the Bronze Age: Material Culture and Social Developments, 770–481 B.C." In Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (editors), The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C., pp. 450–544. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1148 p. ISBN 0-521-47030-7, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

Further reading

- Author? (date?). "Tan Sitong 'Hua-Yi zhi bian' sixiang de yanjin" 谭嗣同"华夷之辨"思想的演进 ["The evolution of Tan Sitong's thinking on the 'Hua-Yi distinction'"]. Retrieved on January 16, 2009. Google translation.

- Fan Wenli 樊文礼 (2004). "'Hua-Yi zi bian' yu Tangmo Wudai shiren de Hua-Yi guan – shiren qunti dui Shatuo zhengquan de rentong" "华夷之辨"与唐末五代士人的华夷观–士人群体对沙陀政权的认同 ["The 'Hua-Yi distinction' and scholar-officials' view of Hua and Yi in the late Tang and Five Dynasties: their recognition of the Shatuo regime"]. Yantai shifan xueyuan xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) 烟台师范学院学报 (哲学社会科学版) ["Bulletin of the Yantai Normal Academy (Philosophy and Social Science edition)"] 21.3. ISSN : 1003-5117(2004)03-0028-05. Google translation.

- Geng Yunzhi 耿云志 (2006). "Jindai sixiangshi shang de minzuzhuyi" 近代思想史上的民族主义 ["Nationalism in modern intellectual history"]. Shixue yuekan 史学月刊 ["Journal of Historical Science"] 2006.6. Retrieved on January 16, 2009. Google translation.

- Guan Jiayue 關嘉耀 (date?). "'Hua-Yi zhi bian' yu wenhua zhongxin zhuyi" 「華夷之辨」與文化中心主義 ["The Hua-Yi distinction and cultural [sino]centrism"] Google translation.

- He Yingying 何英莺 (date?). "Hua-Yi sixiang he Shenguo sixiang de chongtu: lun Zhong-Ri guanxi de fazhan" 华夷思想和神国思想的冲突一一论明初中日关系的发展 [The conflict between the Hua-Yi conception and the Divine-Land conception: on China-Japan relations in the early Ming]. Source? Retrieved on February 9, 2009.

- Huang Shijian 黄时鉴 (date?). "Ditu shang de 'Tianxia guan'" 地图上的"天下观" ["The 'All-under-heaven' conception on maps"]. From Zhongguo cehui 中国测绘. Google translation.

- Liu Lifu 刘立夫 and Heng Yu 恆毓 (2000). "Yi-Xia zhi bian yu Fojiao" 夷夏之辨與佛教 ["The Yi-Xia distinction and Buddhism"]. Retrieved on January 16, 2009. Google translation.

- Pang Naiming 庞乃明 (2008). "Guoji zhengzhi xin yinsu yu Mingchao houqi Hua-Yi zhi bian'" 国际政治新因素与明朝后期华夷之辨 ["A new factor in international politics and the Hua-Yi distinction in the late Ming dynasty"]. Qiushi xuekan 求是学刊 ["Seeking Truth"] 35.4. Google translation.