Howland Island

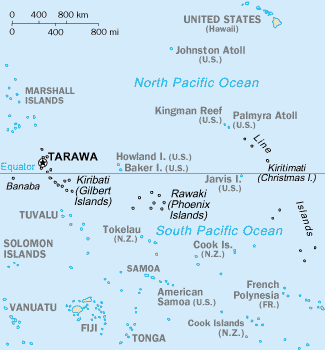

Howland Island /ˈhaʊlənd/ is an uninhabited coral island located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about 1,700 nautical miles (3,100 km) southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia and is an unincorporated, unorganized territory of the United States. Geographically, together with Baker Island it forms part of the Phoenix Islands. For statistical purposes, Howland is grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands.

Howland is located at 0°48′24″N 176°36′59″W / 0.80667°N 176.61639°WCoordinates: 0°48′24″N 176°36′59″W / 0.80667°N 176.61639°W.[1] It covers 450 acres (1.8 km2), with 4 miles (6.4 km) of coastline. The island has an elongated plantain-shape on a north-south axis. There is no lagoon.

Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge consists of the 455-acre (1.84 km2) island and the surrounding 32,074 acres (129.80 km2) of submerged land. The island is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as an insular area under the U.S. Department of the Interior and is part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

The atoll has no economic activity. It is perhaps best known as the island Amelia Earhart was searching for but never reached when her airplane disappeared on July 2, 1937, during her planned round-the-world flight. Airstrips constructed to accommodate her planned stopover were subsequently damaged, were not maintained and gradually disappeared. There are no harbors or docks. The fringing reefs may pose a maritime hazard. There is a boat landing area along the middle of the sandy beach on the west coast, as well as a crumbling day beacon. The island is visited every two years by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[2]

Flora and fauna

The climate is equatorial, with little rainfall and intense sunshine. Temperatures are moderated somewhat by a constant wind from the east. The terrain is low-lying and sandy: a coral island surrounded by a narrow fringing reef with a slightly raised central area. The highest point is about six meters above sea level.

There are no natural fresh water resources.[3] The landscape features scattered grasses along with prostrate vines and low-growing pisonia trees and shrubs. A 1942 eyewitness description spoke of "a low grove of dead and decaying kou trees" on a very shallow hill at the island's center. In 2000, a visitor accompanying a scientific expedition reported seeing "a flat bulldozed plain of coral sand, without a single tree" and some traces of building ruins.[4] Howland is primarily a nesting, roosting and foraging habitat for seabirds, shorebirds and marine wildlife.

The U.S. claims an Exclusive Economic Zone of 200 nautical miles (370 km) and a territorial sea of 12 nautical miles (22 km) around the island.

Since Howland Island is uninhabited, no time zone is specified. It lies within a nautical time zone which is 12 hours behind UTC.

History

Prehistoric settlement

Sparse remnants of trails and other artifacts indicate a sporadic early Polynesian presence. A canoe, a blue bead, pieces of bamboo, and other relics of early settlers have been found.[N 1] The island's prehistoric settlement may have begun about 1000 BC when eastern Melanesians traveled north[6] and may have extended down to Rawaki, Kanton, Manra and Orona of the Phoenix Islands, 500 to 700 km southeast. K.P. Emery, an ethnologist for Honolulu's Bernice P. Bishop Museum, indicated that settlers on Manra Island were apparently of two distinct groups, one Polynesian and the other Micronesian,[7] hence the same might have been true on Howland Island, though no proof of this has been found.

The difficult life on these isolated islands along with unreliable fresh water supplies may have led to the dereliction or extinction of the settlements, much the same as other islands in the area (such as Kiritimati and Pitcairn) were abandoned.[8]

Sightings by whalers

Captain George B. Worth of the Nantucket whaler Oeno sighted Howland around 1822 and called it Worth Island.[9][10] Daniel MacKenzie of the American whaler Minerva Smith was unaware of Worth's sighting when he charted the island in 1828 and named it after his ship's owners[11] on December 1, 1828. Howland Island was at last named on September 9, 1842 after a lookout who sighted it from the whaleship Isabella under Captain Geo. E. Netcher of New Bedford.

U.S. possession and guano mining

Howland Island was uninhabited when the United States took possession of it under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The island was a known navigation hazard for many decades and several ships were wrecked there. Its guano deposits were mined by American companies from about 1857 until October 1878, although not without controversy.

Captain Geo. E. Netcher of the Isabella informed Captain Taylor of its discovery. As Taylor had discovered another guano island in the Indian Ocean, they agreed to share the benefits of the guano on the two islands. Taylor put Netcher in communication with Alfred G. Benson, president of the American Guano Company, which was incorporated in 1857.[12] Other entrepreneurs were approached as George and Matthew Howland, who later became members of the United States Guano Company, engaged Mr. Stetson to visit the Island on the ship Rousseau under Captain Pope. Mr. Stetson arrived on the Island in 1854 and described it as being occupied by birds and a plague of rats.[13]

The American Guano Company established claims in respect to Baker Island and Jarvis Island which was recognised under the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856. Benson tried to interest the American Guano Company in the Howland Island deposits, however the company directors considered they already had sufficient deposits. In October 1857 the American Guano Company sent Benson's son Arthur to Baker and Jarvis Islands to survey the guano deposits. He also visited Howland Island and took samples of the guano. Subsequently Alfred G. Benson resigned from the American Guano Company and together with Netcher, Taylor and George W. Benson formed the United States Guano Company to exploit the guano on Howland Island, with this claim being recognised under the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856.[12]

However when the United States Guano Company dispatched a vessel in 1859 to mine the guano they found that Howland Island was already occupied by men sent there by the American Guano Company. The companies ended up in New York state court,[N 2] with the American Guano Company arguing that United States Guano Company had in effect abandoned the island, since the continual possession and actual occupation required for ownership by the Guano Islands Act did not occur. The end result was that both companies were allowed to mine the guano deposits, which were substantially depleted by October 1878.[14]

In the late 19th Century there were British claims on the island, as well as attempts at setting up mining. John T. Arundel and Company, a British firm using laborers from the Cook Islands and Niue, occupied the island from 1886 to 1891.[15]

To clarify American sovereignty, Executive Order 7368 was issued on May 13, 1936.[16]

Itascatown (1935–42)

In 1935, a brief attempt at colonization was made, part of THE Baker, Howland and Jarvis Colonization Scheme administered by the Department of Commerce to establish a permanent U.S. presence on the equatorial Line Islands. It began with a rotating group of four alumni and students from the Kamehameha School for Boys, a private school in Honolulu. Although the recruits had signed on as part of a scientific expedition and expected to spend their three-month assignment collecting botanical and biological samples, once out to sea they were told, "Your names will go down in history" and that the islands would become "famous air bases in a route that will connect Australia with California".

The settlement was named Itascatown after the USCGC Itasca that brought the colonists to Howland and made regular cruises between the other Line Islands during that era. Itascatown was a line of a half-dozen small wood-framed structures and tents near the beach on the island's western side. The fledgling colonists were given large stocks of canned food, water, and other supplies including a gasoline powered refrigerator, radio equipment, complete medical kits and (characteristic of that era) vast quantities of cigarettes. Fishing provided much-needed variety for their diet. Most of the colonists' endeavors involved making hourly weather observations and gradually developing a rudimentary infrastructure on the island, including the clearing of a landing strip for airplanes. During this period the island was on Hawaii time, which was then 10.5 hours behind UTC.[N 3] Similar colonization projects were started on nearby Baker Island, Jarvis Island and two other islands.

Kamakaiwi Field

Ground was cleared for a rudimentary aircraft landing area during the mid-1930s, in anticipation that the island might eventually become a stopover for commercial trans-Pacific air routes and also to further U.S. territorial claims in the region against rival claims from Great Britain. Howland Island was designated as a scheduled refueling stop for American pilot Amelia Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan on their round-the-world flight in 1937. Works Progress Administration (WPA) funds were used by the Bureau of Air Commerce to construct three graded, unpaved runways meant to accommodate Earhart's twin-engined Lockheed Model 10 Electra.

The facility was named Kamakaiwi Field after James Kamakaiwi, a young Hawaiian who arrived with the first group of four colonists. He was selected as the group's leader and he spent more than three years on Howland, far longer than the average recruit. It has also been referred to as WPA Howland Airport (the WPA contributed about 20 percent of the $12,000 cost). Earhart and Noonan took off from Lae, New Guinea, and their radio transmissions were picked up near the island when their aircraft reached the vicinity but they were never seen again.

Japanese attacks during World War II

A Japanese air attack on December 8, 1941 by 14 twin-engined Mitsubishi G3M "Nell" bombers of Chitose Kōkūtai, from Kwajalein islands, killed two of the Kamehameha School colonists: Richard "Dicky" Kanani Whaley, and Joseph Kealoha Keliʻhananui. The raid came one day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and damaged the three airstrips of Kamakaiwi Field. Two days later a Japanese submarine shelled what was left of the colony's few buildings into ruins.[18] A single bomber returned twice during the following weeks and dropped more bombs on the rubble of tiny Itascatown. The two survivors were finally evacuated by the USS Helm a U.S. Navy destroyer on January 31, 1942. Howland was occupied by a battalion of the United States Marine Corps in September 1943 and known as Howland Naval Air Station until May 1944.

All attempts at habitation were abandoned after 1944. Colonization projects on the other four islands were also disrupted by the war and ended at this time.[19] No aircraft is known to have ever landed there, although anchorages nearby could be used by float planes and flying boats during World War II. For example, on July 10, 1944, a U.S. Navy Martin PBM-3-D Mariner flying boat (BuNo 48199), piloted by William Hines, had an engine fire and made a forced landing in the ocean offshore of Howland. Hines beached the aircraft and although it burned, the crew escaped unharmed, was rescued by the USCGC Balsam (the same ship that later took Unit 92 to Gardner Island), transferred to a sub chaser and taken to Canton Island.[20]

National Wildlife Refuge

On June 27, 1974, Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton created Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge which was expanded in 2009 to add submerged lands within 12 nautical miles (22 km) of the island. The refuge now includes 648 acres (2.62 km2) of land and 410,351 acres (1,660.63 km2) of water.[21] Along with six other islands, the island was administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. In January 2009, that entity was upgraded to the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument by President George W. Bush.[22]

The island habitat has suffered from the presence from multiple invasive exotic species. Black rats were introduced in 1854 and eradicated in 1938 by feral cats introduced the year before. The cats proved to be destructive to bird species and they were eliminated by 1985. Pacific crabgrass continues to compete with local plants.[23]

Public entry to the island is only by special use permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and it is generally restricted to scientists and educators. Representatives from the agency visit the island on average once every two years, often coordinating transportation with amateur radio operators or the U.S. Coast Guard to defray the high cost of logistical support.[23]

Earhart Light

Colonists, sent to the island to establish possession claims by the United States, built the Earhart Light (0°48′20.48″N 176°37′8.55″W / 0.8056889°N 176.6190417°W), named after Amelia Earhart, as a day beacon or navigational landmark. It is shaped somewhat like a short lighthouse. It was constructed of white sandstone with painted black bands and a black top meant to be visible several miles out to sea during daylight hours. It is located near the boat landing at the middle of the west coast by the former site of Itascatown. The beacon was partially destroyed during early World War II by the Japanese attacks, but it was rebuilt in the early 1960s by men from the U.S. Coast Guard ship Blackhaw.[24][25] By 2000, the beacon was reported to be crumbling and it had not been repainted in decades.[26]

Ann Dearing Holtgren Pellegreno overflew the island in 1967, and Linda Finch did so in 1997, during memorial circumnavigation flights to commemorate Earhart's 1937 world flight. No landings were attempted but both Pellegreno and Finch flew low enough to drop a wreath on the island.[27]

Image gallery

-

Earhart Light with post World War II repairs

-

Aircraft wreckage on Howland

-

Itascatown settlement remains

-

Howland island flora

-

Howland island flora (leeward)

-

Brown boobies

-

Brown boobies

-

Ruddy turnstones

See also

- Howland and Baker islands, includes coverage of the Howland-Baker EEZ

- History of the Pacific Islands

- Phoenix Islands

- List of Guano Island claims

References

- Notes

- ↑ Quote: "Howland's Island, although naturally uninhabitable, gave various indications of early visitors, probably natives drifting from windward islands, whose traces were still visible in the remains of a canoe, a blue bead, pieces of bamboo, and other distinctly characteristic belongings."[5]

- ↑ American Guano Co. v. U.S. Guano Co., 44 Barb. 23 (N.Y. 1865).

- ↑ Quote: Thursday, July 1, 1937... Howland Island was using the 10+30 hour time zone — the same as Hawaii standard time..."[17]

- Citations

- ↑ "Howland Island". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge." fws.gov. Retrieved: April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "United States Pacific Island Wildlife Refuges." CIA: The World Factbook. ISSN 1553-8133. Retrieved: November 25, 2010.

- ↑ Payne, Roger. "At Howland Island, 2000." pbs.org. Retrieved: July 6, 2008.

- ↑ Hague, James D. Web copy "Our Equatorial Islands with an Account of Some Personal Experiences." Century Magazine, Vol. LXIV, No. 5, September 1902. Retrieved: January 3, 2008.

- ↑ Suárez 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ Bryan, E.H. "Sydney Island." janeresture.com. Retrieved: July 7, 2008.

- ↑ Irwin 1992, pp. 176–179.

- ↑ Sharp 1960, p. 210.

- ↑ Bryan 1942, pp. 38–41.

- ↑ Maude 1968, p. 130.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Guano Companies in Litigation--A Case of Interest to Stockholders". New York Times. May 3, 1865. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ↑ Howland, Llewellyn (April 1955). "Howland Island, Its Birds and Rats, as Observed by a Certain Mr. Stetson in 1854" (PDF). Vol. IX, PACIFIC SCIENCE, 95-106. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ↑ "GAO/OGC-98-5 - U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution". U.S. Government Printing Office. November 7, 1997. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ↑ Bryan 1942

- ↑ "Memorandum of Secretary of State Cordell Hull to the President, February 18, 1936." Presidential Private File, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York. Retrieved: March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Long 1999, p. 206.

- ↑ Butler 1999, p. 419.

- ↑ "Howland Island." worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved: October 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Report 48199." vpnavy.org. Retrieved: October 10, 2010.

- ↑ White, Susan. "Welcome to Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge." U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, August 26, 2011. Retrieved: March 20, 2012.

- ↑ Bush, George W. "Establishment of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument: A Proclamation by the President of the United States of America." Washington, D.C.: White House, January 6, 2009. Retrieved: March 20, 2012.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge." U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved: March 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Voyage to Howland Island of the USCGC Kukui." US Coast Guard. Retrieved: October 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Earhart beacon shines from lonely island." Eugene Register-Guard, August 17, 1963. Retrieved: March 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Historic Light Station Information and Photography: Pacific Rim". United States Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved: October 10, 2010.

- ↑ Safford et al. 2003, pp. 76–77.

- Bibliography

- Bryan, Edwin H., Jr. American Polynesia and the Hawaiian Chain. Honolulu, Hawaii: Tongg Publishing Company, 1942.

- Butler, Susan. East to the Dawn: The Life of Amelia Earhart. Cambridge, MA: Da Capa Press, 1999. ISBN 0-306-80887-0.

- "Eyewitness account of the Japanese raids on Howland Island (includes a grainy photo of Itascatown)." ksbe.edu. Retrieved: October 10, 2010.

- Irwin, Geoffrey. The Prehistroric Exploration and Colonisation of the Pacific. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-521-47651-8.

- Long, Elgen M. and Marie K. Long. Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. ISBN 0-684-86005-8.

- Maude, H.E. Of Islands and Men: Studies in Pacific History. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Safford, Laurance F. with Cameron A. Warren and Robert R. Payne. Earhart's Flight into Yesterday: The Facts Without the Fiction. McLean, Virginia: Paladwr Press, 2003. ISBN 1-888962-20-8.

- Sharp, Andrew. The Discovery of the Pacific Islands. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960.

- Suárez, Thomas. Early Mapping of the Pacific. Singapore: Periplus Editions, 2004. ISBN 0-7946-0092-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Howland Island. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Howland Island. |

- Geography, history and nature on Howland Island

- "Historic Light Station Information and Photography: Pacific Rim". United States Coast Guard Historian's Office.

- Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge

- 'Voyage of the Odyssey' – pictures and travelogue

- Howland Island at Infoplease

- Howland Island – Small Island, Big History

| ||||||||||||||||||||||