House of Plantagenet

| House of Plantagenet | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Armorial of Plantagenet | |

| Country | Kingdom of England, Kingdom of France, Lordship of Ireland, Principality of Wales |

| Parent house | Angevins |

| Titles |

|

| Founded | 1126 |

| Founder | Geoffrey V of Anjou |

| Final ruler | Richard III of England |

| Dissolution | 1485 |

| Ethnicity | French, English |

| Cadet branches | |

The House of Plantagenet (/plænˈtædʒənət/ plan-TAJ-ə-nət, also spelt in English sources as Plantaganet, Plantagenett, Plantagenette, Plantaginet, Plantagynett, etc.) was a French family originating from Anjou that held the English throne from 1154 to 1485, starting with the accession of Henry II and ending with the death of Richard III. Within that period, some historians identify the four distinct royal houses of Anjou, Plantagenet, Lancaster, and York.[1]

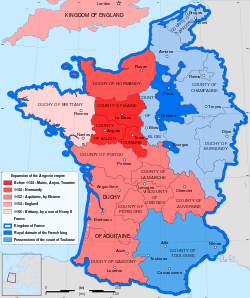

Between 1144 and 1154, two successive Counts of Anjou obtained a vast assemblage of lands, which were retrospectively referred to as the Angevin Empire. The first of these counts, Geoffrey, became Duke of Normandy in 1144. His successor, Henry, added Aquitaine to the empire through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152. In 1154, Henry successfully pursued a claim to the English throne as a result of the reign of his maternal grandfather, Henry I of England.[2] Through Henry's fourth son, John, a line of fourteen English kings was produced. The name of Plantagenet, which historians use to reference the entire dynasty, originated in the 15th century and derives from a 12th-century nickname for "Geoffrey".

Under the Plantagenets, England was transformed from a colony, often governed from abroad and considered less significant among European monarchies, into a sophisticated, politically engaged and independent kingdom. This was not necessarily due to the conscious intentions of the Plantagenets. Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Britiain from 1940 to 1945, stated in A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: "When the long tally is added, it will be seen that the British nation and the English-speaking world owe far more to the vices of John than to the labours of virtuous sovereigns."[3][4]

The Plantagenet kings were forced to negotiate the weaknesses that resulted from compromises such as the Magna Carta. These compromises constrained royal power in return for financial and military support. The king was no longer solely the most powerful man in the nation, holding the prerogative of judgement, feudal tribute and warfare. The monarch now had defined duties to the realm, underpinned by a sophisticated justice system. Conflicts with the French, Scots, Welsh and Irish, along with the use of English, which was re-established as the primary language, shaped a distinct national identity. The Plantagenets were also responsible for the construction of significant English buildings, such as King's College, Eton College, Westminster Abbey, Windsor Castle and Welsh castles.

The Plantagenets were conclusively defeated in the Hundred Years' War. Tax raises introduced to support the war effort contributed to the devastation of the English economy. Revolts resulted from the general population's demand for more rights and freedoms. Crime increased as destitute soldiers returned from France, while the nobility raised private armies, feuded and defied the weak leadership of Henry VI. There was continual rivalry among the royal family members. The political and economic situation, combined with the dynasty's 15th-century split into the competing cadet branches of York and Lancaster, eventually resulted in the Wars of the Roses. These events culminated in 1485, when the last Plantagenet king, Richard III, died at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Many historians consider Richard's death as marking the end of the Plantagenet's reign and the English Middle Ages. The succeeding Tudor dynasty centralised royal power, thereby resolving many of the problems that troubled the later Plantagenet monarchs. This centralisation resulted in the stability necessary for the English Renaissance and the beginnings of Early modern Britain.

Origin

The counts of Anjou, of which the Plantagenets were part, descended from Geoffrey II, Count of Gâtinais, and his wife, Ermengarde of Anjou. In 1060, the couple inherited the title via cognatic kinship from an Angevin family that was descended from a noble named Ingelger, and whose recorded history dates from 870.[5][6]

During the 10th and 11th centuries, a power struggle occurred between the counts of Anjou and rulers in northern and western France. Among these rulers were Henry, Duke of Normandy, the rulers of Brittany, Poitou, Blois, and Maine, and the kings of France. The marriage of Geoffrey Plantagenet to Empress Matilda, Henry's only surviving legitimate child and heir to the throne, resulted in the unification of the counts of Anjou and the houses of Normandy and Wessex. As a result of this marriage, Geoffrey's son, Henry II, inherited the English, Norman and Angevin thrones, thus marking the beginning of the Angevin and Plantagenet dynasties.[7]

The marriage was the third attempt of Geoffrey's father—Fulk V, Count of Anjou—to build a political alliance with Normandy. He first espoused his daughter, Alice, to William Adelin, Henry I's heir. However, William drowned in the wreck of the White Ship. Fulk then married another of his daughters, Sibylla, to William Clito, heir to Henry I's older brother, Robert Curthose. Henry I, however, had the marriage annulled to avoid strengthening William's rival claim to his lands. After achieving his goal through the marriage of Geoffrey and Matilda, Fulk relinquished all his titles to Geoffrey and departed to become King of Jerusalem.[8]

Terminology

Plantagenet

It was Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, who adopted Plantagenet as a family name for him and his descendants in the 15th century. Plantegenest (or Plante Genest) had been a 12th-century nickname of Geoffrey, perhaps because his emblem may have been the common broom, (planta genista in medieval Latin).[9] It is uncertain why Richard chose this specific name, but it emphasised Richard's status as Geoffrey's (and six English kings') patrilineal descendant during the Wars of the Roses. The retrospective usage of the name for all of Geoffrey's male descendants was popular in Tudor times, perhaps encouraged by the added legitimacy it gave Richard's great grandson, Henry VIII of England.[10]

Angevins

The adjective Angevin is especially used in English history to refer to the three kings of the Angevin dynasty—Henry II, Richard I and John—who were also counts of Anjou; their characteristics, descendants and the period of history which they covered from the mid-12th to the early-13th centuries. Many historians consider the Angevins /ændʒvɪns/, meaning from Anjou in French, as a distinct English royal house. In addition, Angevin is also used pertaining to Anjou, or any sovereign, government derived from this. As a noun it is used for any native of Anjou or Angevin ruler and as such is also used for other Counts and Dukes of Anjou; including the three kings' ancestors, their cousins who held the crown of Jerusalem and unrelated later members of the French royal family who were granted the titles to form different dynasties amongst which were the Capetian House of Anjou and the Valois House of Anjou.[11] As result there is disagreement between those who consider Henry III to be the first Plantagenet and those who do not make a distinction between Angevin and Plantagenet who consider the first to be Henry II.[12][13][14][15] The term Angevin Empire was coined in 1887 by Kate Norgate. As far as it is known there was no contemporary name for the assemblage of territories which were referred to—if at all—by clumsy circumlocutions such as "our kingdom and everything subject to our rule whatever it may be", or "the whole of the kingdom which had belonged to his father". Whereas the Angevin part of this term has proved uncontentious the empire portion has proved controversial. In 1986 a convention of historical specialists concluded that there had been no Angevin state and no "Angevin Empire" but the term espace Plantagenet was acceptable.[16] Nonetheless, historians have continued to use the term "Angevin Empire".[17]

Angevin kings of England

Arrival in England

When the future Henry II was born in 1133, his grandfather—Henry, king of England—was reportedly delighted, describing the boy as "the heir to the kingdom". The birth reduced the risk that the king's Anglo-Norman realm would pass to his son-in-law's family, should the marriage of Matilda and Count Geoffrey prove childless. The birth of a second son—also called Geoffrey—raised the possibility that—in accordance to French inheritance custom of the period—the Anglo-Norman maternal inheritance would go to Henry and the Angevin paternal inheritance to Geoffrey. This would have again divided the Anglo-Norman lands from those of Anjou.[18] However—in what was a precursor of the regular internecine strife that would plague the Plantagenets—the king quarreled with Count Geoffrey and Matilda as they attempted to develop an alternative power base that would ensure the succession. The result was that when King Henry died in November 1135 the couple were in their own dominions. This allowed Matilda's cousin—Stephen—to race from his lands in Boulogne and seize the crown of England.[19]

Henry's father, Count Geoffrey, had little interest in England, but commenced a ten-year struggle for the duchy of Normandy.[20] His mother Matilda created a second front by invading England in 1139 and in doing so instigating the civil war known as the Anarchy. In 1141 this proved decisive when she captured Stephen at the battle of Lincoln. The resulting collapse in Stephen's support enabled Geoffrey to push on with the conquest of Normandy over the next four years. However, in England Matilda threw away her winning position and Stephen was released in a hostage exchange for Matilda's half-brother Robert. Henry was sent repeatedly to England from the age of nine to be the male figurehead of the campaigns, as it became apparent that if England was conquered it was his father's intention that Henry would become king. In 1150 Geoffrey also transferred the title of Duke of Normandy to Henry although Geoffrey retained the dominant role in governance of the duchy.[21]

Three fortuitous events allowed Henry to finally bring the conflict to a successful conclusion:

- In 1151 Count Geoffrey died before having time to complete his plan to divide his inheritance between Henry and Henry's brother—Geoffrey—who would have received Anjou. According to William of Newburgh writing in the 1190s, the dying Geoffrey decided that Henry would have the paternal and maternal inheritances while he needed the resources to overcome Stephen, and left instructions that his body should not be buried until Henry swore an oath that, once England and Normandy were secured the younger Geoffrey would have Anjou.[22] Henry's brother Geoffrey died in 1154, too soon to receive Anjou, but not before he was installed as count in Nantes, after Henry aided a rebellion by its citizens against their previous lord.[23]

- Louis VII of France divorced Eleanor of Aquitaine—on 18 March 1152—whom Henry quickly married—18 May 1152—greatly increasing his resources and power with the acquisition of Duchy of Aquitaine.[24]

- In 1153 Stephen's son—Eustace—died. This disheartened Stephen, who had also recently been widowed, and he gave up the fight. The Treaty of Wallingford repeated the peace offer that Matilda rejected in 1142, recognising Henry as Stephen's heir, guaranteeing Stephen's second son—William—his rights to his family estates and allowed Stephen to be king for life. Stephen did not live long and so Henry inherited in late 1154.[25]

Angevin zenith

Both of Henry's siblings—Geoffrey (1134–1158) and William (1136–1164)— died unmarried and without descendants. However, the tempestuous marriage of Henry and Eleanor—who already had two daughters by her first marriage to King Louis: Marie and Alix—produced eight children in 13 years:[26]

- William (1153–1156)

- Henry (1155–1183)

- Matilda (1156–1189)

- Richard (1157–1199)

- Geoffrey (1158–1186)

- Eleanor (1161–1214)—married Alfonso VIII of Castile, her daughters included Queen Berengaria of Castile, Urraca, Queen of Portugal, Blanche, Queen of France and Eleanor, Queen of Aragon.[27]

- Joan (1165–1199)

- John (1166–1216)

Henry faced many challenges to secure possession of his father's and grandfathers' lands that required the reassertion and extension of old suzerainties.[28] In 1162, he saw an opportunity to re-establish what he saw as his rights over the church in England by appointing his friend Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury when the incumbent Theobald died. However, Becket proved to be an inept politician whose defiance alienated the king and his counsellors. Henry and Becket clashed repeatedly: over church tenures, Henry's brother's marriage and taxation. Henry reacted by getting Becket, and other members of the English episcopate, to recognise sixteen ancient customs—governing relations between the king, his courts and the church—in writing for the first time in the Constitutions of Clarendon. When Becket tried to leave the country without permission, Henry attempted to ruin him by laying a number of suits relating to Becket's time as chancellor. In response Becket fled into exile for five years. Relations later improved, allowing Becket's return, but soured again when Becket saw the coronation of Henry's son as coregent by the Archbishop of York as a challenge to his authority and excommunicated those who had offended him. When he heard the news, Henry said: "What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk". Three of Henry's men killed Becket in Canterbury Cathedral after Becket resisted a botched arrest attempt. Within Christian Europe Henry was widely considered complicit in Becket's death. The opinion of this transgression against the church made Henry a pariah, so in penance he walked barefoot into Canterbury Cathedral where he was scourged by monks.[29]

Pope Adrian IV had given Henry a papal blessing to expand his power into Ireland to reform the Irish church. Originally this would have allowed some territory to be granted to Henry's brother, William, but other matters had distracted Henry and William was now dead.[30] In 1171 Henry invaded Ireland to assert his overlordship following alarm at the success of knights he had allowed to recruit soldiers in England and Wales. These knights had assumed the role of colonisers and accrued autonomous power. Instead Henry's designs were made plain when he gave the lordship of Ireland to his youngest son, John.[31] In 1172 Henry II tried to give his landless youngest son John a wedding gift of the three castles of Chinon, Loudun and Mirebeau. This angered the 18-year old Young King who had yet to receive any lands from his father and prompted a rebellion by Henry II's wife and three eldest sons. Louis VII supported the rebellion to destabilise his Henry II. William the Lion and other subjects of Henry II also joined the revolt and it took 18 months for Henry to force the rebels to submit to his authority.[32] In Le Mans in 1182, Henry II gathered his children to plan a partible inheritance in which his eldest son (also called Henry) would inherit England, Normandy and Anjou; Richard the Duchy of Aquitaine; Geoffrey Brittany, and John Ireland. This degenerated into further conflict. The younger Henry rebelled again before he died of dysentery and, in 1186, Geoffrey died after a tournament accident. In 1189 Richard and Philip II of France took advantage of Henry's failing health and forced him to accept humiliating peace terms, including naming Richard as his sole heir.[33] Two days later the old king died, defeated and miserable in the knowledge that even his favoured son John had rebelled. This fate was seen as the price he paid for the murder of Beckett.[34]

On the day of Richard's English coronation there was a mass slaughter of the Jews, described by Richard of Devizes as a "holocaust".[35] Quickly putting the affairs of the Angevin Empire in order he departed on Crusade to the Middle East in early 1190. Opinions of Richard amongst his contemporaries were mixed. He had rejected and humiliated the king of France's sister; deposed the well-connected king of Cyprus and afterwards sold the island; insulted and refused spoils of the Third Crusade to nobles like Leopold V, Duke of Austria, and was rumoured to have arranged the assassination of Conrad of Montferrat. His cruelty was demonstrated by his massacre of 2,600 prisoners in Acre.[36] However, Richard was respected for his military leadership and courtly manners. He achieved victories in the Third Crusade but failed to capture Jerusalem, retreating from the Holy Land with a small band of followers.[37]

Richard was captured by Leopold on his return journey. Custody was passed to Henry the Lion and a tax of 25 percent of movables and income was required to pay the ransom of 100,000 marks, with a promise of 50,000 more. Philip II of France had overrun great swathes of Normandy while King John of England controlled much of the remainder of Richard's lands. But, on his return to England, Richard forgave John and re-established his control. Leaving England in 1194 never to return, Richard battled Phillip for the next five years for the return of the holdings seized during his incarceration. Close to total victory he was injured by an arrow during the siege of Château de Châlus-Chabrol and died after lingering injured for ten days.[38]

Decline and the loss of Anjou

Richard's failure in his duty to provide an heir caused a succession crisis. Anjou, Brittany, Maine and Touraine chose Richard's nephew and nominated heir, Arthur, while John succeeded in England and Normandy. Yet again Philip II of France took the opportunity to destabilise the Plantagenet territories on the European mainland, supporting his vassal Arthur's claim to the English crown. When Arthur's forces threatened his mother, John won a significant victory, capturing the entire rebel leadership at the Battle of Mirebeau.[39]

Arthur was murdered, it was rumoured by John's own hands, and his sister Eleanor would spend the rest of her life in captivity. John's behaviour drove numerous French barons to side with Phillip. The resulting rebellions by the Norman and Angevin barons broke John's control of the continental possessions, leading to the de facto end of the Angevin Empire, even though Henry III would maintain the claim until 1259.[40]

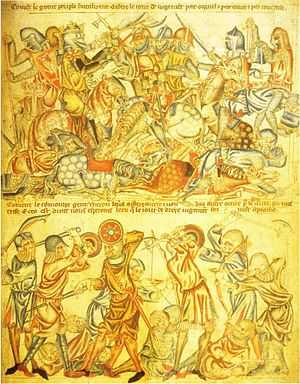

.jpg)

After re-establishing his authority in England, John planned to retake Normandy and Anjou. The strategy was to draw the French from Paris while another army, under Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor, attacked from the north. However, his allies were defeated at the Battle of Bouvines in one of the most decisive and symbolic battles in French history.[41] The battle had both important and high profile consequences.[42] John's nephew Otto retreated and was soon overthrown while King John agreed to a five-year truce. Philip's decisive victory was crucial in ordering politics in both England and France. The battle was instrumental in forming the absolute monarchy in France.[43] The defeat in France weakened John's authority in England and he was forced to agree to the limitation of royal power documented in the treaty called Magna Carta between him and his senior magnates. While the principles of Magna Carta formed the basis of every constitutional battle through the 13th and 14th centuries both John and the barons rapidly attempted to rescind the terms of Magna Carta, leading to the First Barons' War. in which the rebel barons invited an invasion by Prince Louis—the husband of Blanche, granddaughter of Henry II by his daughter Eleanor and Alfonso VIII of Castile— who invaded England but before the conflict was conclusively decided, in October 1216, John died .[44] Some historians consider John's death marks the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty.[1]

Main line

Baronial conflict and the establishment of Parliament

Descent from the Angevins (legitimate and illegitimate) via John is widespread including all subsequent monarchs of England and the United Kingdom. John had five legitimate children with Isabella:

- Henry III – king of England for most of the 13th century.

- Richard – a noted European leader and King of the Romans in the Holy Roman Empire.[45]

- Joan – married Alexander II of Scotland, becoming his queen consort.[46]

- Isabella – married the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II.[47]

- Eleanor – married William Marshal's son (also called William) and, later, English rebel Simon de Montfort.[48]

In addition John had illegitimate children with a number of mistresses, including nine sons—Richard, Oliver, John, Geoffrey, Henry, Osbert Gifford, Eudes, Bartholomew and (probably) Philip—and three daughters—Joan, Maud and (probably) Isabel.[49] Of these Joan was the best known, since she married Prince Llywelyn the Great of Wales.[50]

William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke was appointed the protector of the nine-year-old Henry III on his father's death. Without John as a focus for dissent support for Louis ebbed away—Marshall's victories at the battles of Lincoln and Dover in 1217 led to Louis renouncing his claims with the Treaty of Lambeth.[51] The Marshal Protectorate achieved reconciliation with the reissue of an amended Magna Carta as a basis for future government.[52] Despite the 1217 Treaty of Lambeth, hostilities continued and Henry was forced to make significant constitutional concessions to the newly crowned Louis VIII of France and Henry's stepfather Hugh X of Lusignan. Between them, they overran much of the remnants of Henry's continental holdings, further eroding the Angevin's grip on the continent. Henry saw such similarities between himself and England's then patron saint Edward the Confessor in his struggle with his nobles[53] that he gave his first son the Anglo-Saxon name Edward and built the saint a magnificent, still-extant shrine.[54] The barons were resistant to the cost in men and money required to support a foreign war to restore Plantagenet holdings on the continent. In order to motivate his barons, and facing a repeat of the situation his father faced, Henry III reissued Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest in return for a tax that raised the incredible sum of £45,000. This was enacted in an assembly of the barons, bishops and magnates that created a compact in which the feudal prerogatives of the king were debated and discussed in the political community.[55]

Henry III had nine children:[56]

- Edward I of England

- Margaret, Queen of Scots—(1240 to 1275)— her three children predeceased her husband Alexander III of Scotland, with the result that the crown of Scotland became vacant when their only grandchild —Margaret, Maid of Norway— drowned in 1290.[57]

- Beatrice, Countess of Richmond—(1242 to 1275), married firstly John de Montfort of Dreux and secondly John II, Duke of Brittany

- Edmund Crouchback—(1245 to 1296) —After defeating Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, in the Second Barons' War, Henry granted Edmund the titles and estates of Montfort, including the Earldom of Leicester, and also added later grants of the Earldom of Lancaster and of Ferrers. Edmund was also Count of Champagne and Brie from 1276 by right of his wife.[58] Henry IV of England would later use his descent from Edmund to legitimise his claim to the throne, even making the spurious claim that Edmund was the elder son of Henry but had been passed over as king because of his deformity.[59] By his second marriage to Blanche of Artois, the widow of the King of Navarre, Edmund was positioned at the centre of the European aristocracy. Blanche's daughter Joan I of Navarre was queen regnant of Navarre and through her marriage to Philip IV of France was queen consort of France. Edmund's son Thomas became the most powerful nobleman in England adding the Earldoms of Lincoln and Salisbury through marriage to the heiress of Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln. Thomas's income was £11,000 per annum—double that of the next wealthiest earl.[60]

- Four further children who died young; Richard—(1247 to 1256), John—(1250–1256), William—(c. 1251/1252 to 1256), Katherine of England—(c. 1252/3 to 1257) and Henry—died young with no recorded dates.

The pope had offered Henry's brother Richard the Kingdom of Sicily but he recognised that the cost of making this claim real was prohibitive. Matthew Paris wrote that Richard responded to the price by saying, "You might as well say, 'I make you a present of the moon—step up to the sky and take it down'". Instead, Henry purchased the kingdom for his son Edmund Crouchback, 1st Earl of Lancaster, which angered many powerful barons. Bankrupted by his military expenses, Henry was forced to agree to the Provisions of Oxford by barons led by his brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort, under which his debts were paid in exchange for substantial reforms. He was also forced to agree to the Treaty of Paris with Louis IX of France, acknowledging the loss of the Dukedom of Normandy, Maine, Anjou and Poitou, but retaining the Channel Islands. The treaty held that "islands (if any) which the king of England should hold", he would retain "as peer of France and Duke of Aquitaine".[61] In exchange Louis withdrew his support for English rebels, ceded three bishoprics and cities, and was to pay an annual rent for possession of Agenais.[62] This was one of the root causes of the Hundred Years War with disagreements about the meaning of the treaty beginning as soon as it was signed.[63] English kings were sovereign in England, but were vassals to the kings of France for their continental lands.[64]

Friction intensified between the barons and the king. The barons, under Simon de Montfort, captured most of South East England in what became known as the Second Barons' War. At the Battle of Lewes in 1264, Henry and Prince Edward were defeated and taken prisoner. Montfort summoned the Great Parliament, regarded as the first Parliament worthy of the name because it was the first time the cities and burghs had been instructed to send representatives.[65] Edward escaped and raised an army, defeating and killing Montfort at the Battle of Evesham in 1265.[66] Savage retribution was exacted on the rebels and authority was restored to Henry. Edward, having pacified the realm, left England to join Louis IX on the Ninth Crusade. He was one of the last crusaders in the tradition aiming to recover the Holy Lands. Louis died before Edward's arrival, but Edward decided to continue. The result was anticlimactic; Edward's small force limited him to the relief of Acre and a handful of raids. Surviving a murder attempt by an assassin, Edward left for Sicily later in the year, never to return on crusade. The stability of England's political structure was demonstrated when Henry III died and his son succeeded as Edward I; the barons swore allegiance to Edward even though he did not return for two years.[67]

Constitutional change and the reform of feudalism

Edward's first marriage in 1254 was to Eleanor of Castile, a daughter of King Ferdinand of Castile also a great grandson of Henry II. Edward and Eleanor had sixteen children, of whom five daughters survived into adulthood, but only one boy outlived Edward:[68]

- Eleanor, Countess of Bar—(1264/69 to 1298)

- three daughters and two sons born between 1265 to 1271 who died young between 1265 to 1274 with little historical trace: Joan, John, Henry, Alice, and Juliana or Katherine

- Joan, Countess of Hertford—(1272 to 1307).

- Alphonso, Earl of Chester—(1273 to 1284)

- Margaret, Duchess of Brabant

- Mary of Woodstock—(1278 to 1332) who became a nun

- Isabella— born and died in 1279

- Elizabeth, Countess of Hereford—(1282 to 1316): among her eleven children were Earls of Hereford, Essex, and Northampton, and Countesses of Ormond and Devon

- Edward II of England

- Two more daughters who died young: Beatrice and Blanche

Edward's second marriage in 1299 was to Margaret of France who was the daughter of Philip III of France. Margaret and Edward had two sons, both of whom lived into adulthood, and a daughter who died as a child.[69]

- Thomas, Earl of Norfolk—(1300–1338) his daughter, Margaret inherited his estates, and her grandson Thomas Mowbray was the first of the Dukes of Norfolk. However, Mowbray was exiled by Henry IV and stripped of his titles.

- Edmund, Earl of Kent—(1301 to 1330) was executed by order of Mortimer and Queen Isabella. His daughter Joan inherited his estates and married her cousin Edward, the Black Prince. Their son was Richard II.

- Eleanor—(1306 to 1311)

Because of his legal reforms, Edward is sometimes called The English Justinian,[70] although whether he was a reformer or an autocrat responding to events is debated. His military campaigns left him in debt, so that he had to gain wider national support for his policies among the lesser landowners and merchants, to enable him to raise taxes through frequently summoned Parliaments. When Philip IV of France confiscated the duchy of Gascony in 1294, Edward needed more money to wage war in France. To gain financial support for this war effort, Edward summoned a precedent-setting assembly known as the Model Parliament, which included barons, clergy, knights of the shires, and burgesses.[70] Edward imposed his authority on the Church with the Statutes of Mortmain, which prohibited the donation of land to the Church, asserted the rights of the Crown at the expense of traditional feudal privileges, promoted the uniform administration of justice, raised income, and codified the legal system.[71]

Expansion in Britain

From the beginning of his reign Edward I sought to organise his inherited territories. As a devotee of the cult of King Arthur he also attempted to enforce claims to primacy within the British Isles. Wales consisted of a number of princedoms, often in conflict with each other. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd held North Wales in fee to the English king under the Treaty of Woodstock, but had taken advantage of the English civil wars to consolidate his position as Prince of Wales, and maintained that his principality was 'entirely separate from the rights' of England. Edward considered Llywelyn 'a rebel and disturber of the peace'. Edward's determination, military experience, and skilful use of ships, ended Welsh independence by driving Llywelyn into the mountains. Llywelyn later died in battle. The Statute of Rhuddlan extended the shire system, bringing Wales into the English legal framework. When Edward's son was born he was proclaimed as the first English Prince of Wales. Edward's Welsh campaign produced one of the largest armies ever assembled by an English king in a formidable combination of heavy Anglo-Norman cavalry and Welsh archers that laid the foundations of later military victories in France. Edward spent around £173,000 on his two Welsh campaigns, largely on a network of castles to secure his control.[72]

Edward asserted that the king of Scotland owed him feudal allegiance and intended to create a Union of the Crowns by marrying his son Edward to Margaret, Maid of Norway, who was the sole heir of Alexander III of Scotland.[73] When Margaret died, Edward was invited by the Scottish magnates to resolve the disputed inheritance. Edward obtained recognition from the competitors for the Scottish throne that he had the 'sovereign lordship of Scotland and the right to determine our several pretensions' and decided the case in favour of John Balliol, who duly swore loyalty to him and became king.[74] Edward insisted that Scotland was not independent and that as its sovereign lord he had the right to hear in England appeals against Balliol's judgements, undermining Balliol's authority. In 1295 Balliol entered into an alliance with France,[75] and the next year Edward invaded Scotland, deposing and exiling Balliol.[76]

Edward was less successful in Gascony, which was overrun by the French. His commitments were beginning to outweigh his resources and Edward was forced to reconfirm the Charters (including Magna Carta) to obtain the money he required. A truce and peace treaty the French king restored the duchy of Gascony to Edward. Meanwhile William Wallace had risen in Balliol's name and recovered most of Scotland, before being defeated at the Battle of Falkirk.[77] Robert the Bruce now rebelled and was crowned king of Scotland. Edward died on his way to lead another Scottish campaign.[77]

Edward II's coronation oath on his succession in 1307 was the first to reflect the king's responsibility to maintain the laws that the community "shall have chosen" ("aura eslu").[78] The king was initially popular but faced three challenges: discontent over the financing of wars; his household spending and the role of Piers Gaveston.[79] When Parliament decided that Gaveston should be exiled the king had no choice but to comply.[80] The king engineered Gaveston's return, but was forced to agree to the appointment of Ordainers, led by his cousin Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, to reform the royal household with Piers Gaveston exiled again.[81][82] When Gaveston returned again to England, he was abducted and executed after a mock trial.[83] This brutal act drove Thomas, and his adherents from power. Edward's humiliating defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn by Bruce, confirming Bruce's position as an independent king of Scots, returned the initiative to Lancaster and Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick, who had not taken part in the campaign, claiming that it was in defiance of the Ordinances.[84][85] Edward finally repealed the Ordinances after defeating and executing Lancaster at the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322.[86]

The French monarchy asserted its rights to encroach on Edward's legal rights in Gascony. Resistance to one judgement in Saint-Sardos resulted in Charles IV declaring the duchy forfeit. Charles's sister, Queen Isabella, was sent to negotiate and agreed to a treaty that required Edward to pay homage in France to Charles. Edward resigned Aquitaine and Ponthieu to his son, Edward, who travelled to France to give homage in his stead. With the English heir in her power, Isabella refused to return to England unless Edward II dismissed his favourites and also formed a relationship with Roger Mortimer.[87] The couple invaded England and, joined by Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, captured the king.[88] Edward II abdicated on the condition that his son would inherit the throne rather than Mortimer. He is generally believed to have been murdered at Berkeley Castle by having a red-hot poker thrust into his bowels.[58] A coup by Edward III ended four years of control by Isabella and Mortimer. Roger Mortimer was executed. Though removed from power, Isabella was treated well, living in luxury for the next 27 years.[89]

Conflict with the House of Valois

In 1328 Charles IV of France died without a male heir. His cousin Phillip of Valois and Queen Isabella, on behalf of her son Edward, were the major claimants to the throne. Philip, as senior grandson of Philip III of France in the male line, became king over Edward's claim as a matrilineal grandson of Philip IV of France, following the precedents of Philip V's succession over his niece Joan II of Navarre and Charles IV's succession over his nieces. Not yet in power, Edward III paid homage to Phillip as Duke of Aquitaine and the French king continued to assert feudal pressure on Gascony, leading Edward to go to war.[90] Edward proclaimed himself king of France to encourage the Flemish to rise in open rebellion against the French king. The conflict, known as the Hundred Years War saw a significant England naval victory at the Battle of Sluys.[91] eventually followed by a victory on land at Crécy, leaving Edward free to capture the important port of Calais. A subsequent victory against Scotland at the Battle of Neville's Cross resulted in the capture of David II and reduced the threat from Scotland.[92] The Black Death brought a halt to Edward's campaigns by killing between a third to more than half of his subjects.[93][94] The only Plantagenet known to have died from the Black Death was Edward III's daughter Joan on her way to marry Pedro of Castile.[95]

Edward, the Black Prince, resumed the war with destructive chevauchées starting from Bordeaux. His army was caught by a much larger French force at Poitiers, but the ensuing battle was a decisive English victory resulting in the capture of John II of France. The Second Treaty of London was signed, which promised a four million écus ransom. It was guaranteed by the Valois family hostages being held in London, while John returned to France to raise his ransom. Edward gained possession of Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine and the coastline from Flanders to Spain, restoring the lands of the former Angevin Empire. The hostages quickly escaped back to France. John, horrified that his word had been broken, returned to England and died there. Edward invaded France in an attempt to take advantage of the popular rebellion of the Jacquerie, hoping to seize the throne. Although no French army stood against him, he was unable to take Paris or Rheims. In the subsequent Treaty of Brétigny he renounced his claim to the French crown, but greatly expanded his territory in Aquitaine and confirmed his conquest of Calais.[96]

Fighting in the Hundred Years' War spilled from the French and Plantagenet lands into surrounding realms, including the dynastic conflict in Castile between Peter of Castile and Henry II of Castile. The Black Prince allied himself with Peter, defeating Henry at the Battle of Nájera before falling out with Peter, who had no means to reimburse him, leaving Edward bankrupt. The Plantagenets continued to interfere and John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, the Black Prince's brother, married Peter's daughter Constance, claiming the Crown of Castile in the name of his wife. He arrived with an army, asking John I to give up the throne in favour of Constance. John declined; instead his son married John of Gaunt's daughter, Catherine of Lancaster, creating the title Prince of Asturias for the couple.[97]

Charles V of France resumed hostilities when the Black Prince refused a summons as Duke of Aquitaine and his reign saw the Plantagenets steadily pushed back in France.[98] The prince fell ill and returned to England where he soon died.[99] John of Gaunt assumed leadership in France but the English lost towns and territory including Poitiers and Bergerac.[100][101] In addition English dominance at sea was reversed by defeat at the Battle of La Rochelle which undermined seaborne trade and threatened Gascony.[102]

Descendants of Edward III

The fecund marriage of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault produced thirteen children and 32 grandchildren.[103]

- Edward (1330–1376)—he married his cousin Joan of Kent who was a granddaughter of Edward I and had two legitimate sons.

- Edward—(1365–1371/2)

- Richard II of England—(1367–1400)

- Isabella of England, Lady of Coucy—(1332–1382), married Enguerrand II, Lord of Coucy and had two daughters.

- Joan of England (1335–1348)

- William—(1334/6–1337)

- Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence—(1338–1368), had one daughter

- Philippa, 5th Countess of Ulster—(1355–1378/81), it was through Philippa the House of York asserted it had a superior claim to the throne to the House of Lancaster by cognatic kinship. Philippa's granddaughter and heir, Anne Mortimer married Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge the heir to the Duke of York. By her daughter Elizabeth Mortimer Phillipa was also the ancestor of the Earls of Nothumberland and Cliiford family who were significant supporters of Lancaster in the Wars of the Roses.

- John of Gaunt—(1340–1399), married Blanche of Lancaster who was the heiress to the duchy of Lancaster and a direct descendent of Henry III,

- Philippa of Lancaster—(1360 –1415), married John I of Portugal.

- John of Lancaster—(c.1362/1364); died in early infancy.

- Elizabeth of Lancaster—(1364–1426), married John Hastings, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, John Holland, 1st Duke of Exeter and John Cornwall, 1st Baron Fanhope.

- Edward of Lancaster—(1365–1365).

- John of Lancaster—(1366); died in early infancy.

- Henry IV—(1367–1413).

- Isabella of Lancaster—(b.1368); died young.

- John married secondly Constance of Castile in an attempt to win the throne of Castile that was unsuccessful. The marriage produced two children.

- Catherine of Lancaster— (1372–1418), married Henry III of Castile and whose descendants number Catherine of Aragon and kings of Castile and Aragon.

- John—(1374–1375)

- John married thirdly Katherine Swynford on 13 January 1396 after a long affair. The four children of the couple were all born before this date and were given the name Beaufort. The Pope legitimised them in 1396, as did Richard II by charter which also excluded them from the line of succession.

- John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset—(c. 1371/1372–1410), grandfather of Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby the mother of Henry VII.

- Cardinal Henry Beaufort—(1375–1447)

- Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter—(1377–1427)

- Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland—(1379–1440), Joan's son, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, and grandson, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, were both leading Yorkist supporters.

- Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York—(1341–1402), Edward III raising Edmund to the rank of Duke founded the House of York.

- Edward, 2nd Duke of York—(1373–1414), was killed at the Battle of Agincourt.

- Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester—(1374–1416)

- Richard, 3rd Earl of Cambridge—(1375/1415)

- Blanche—(1342), died young.

- Mary of Waltham—(1344–1362), married John V, Duke of Brittany. No issue.

- Margaret—(1346–1361), married John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. No issue.

- Joan—(born 1351)

- Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester—(1355–1397) was murdered or executed for treason by the order of Richard II; his daughter Anne, married into the Stafford family and descendants were Dukes of Buckingham. Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, descended on his father's side from Thomas of Woodstock, and on his mother's side from John Beaufort.

Demise of the main line

The Black Prince's 10-year-old son succeeded as Richard II of England on the death of his grandfather, with government in the hands of a regency council.[104] The poor state of the economy as his government levied a number of poll taxes to finance military campaigns, resulted in the Peasants' Revolt in 1381,[105] followed by brutal reprisals against the rebels.[106] The king's uncle Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester, Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel, and Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick, became known as the Lords Appellant when they sought to impeach five of the king's favourites and restrain what was increasingly seen as tyrannical and capricious rule.[107] Later they were joined by Henry Bolingbroke, the son and heir of John of Gaunt, and Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk. Initially, they were successful in establishing a commission to govern England for one year, but they were forced to rebel against Richard, defeating an army under Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, at the skirmish of Radcot Bridge. Richard was reduced to a figurehead with little power. As a result of the Merciless Parliament, de Vere and Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk, who had fled abroad, were sentenced to death in their absence. Alexander Neville, Archbishop of York, had all of his worldly goods confiscated. A number of Richard's council were executed. Following John of Gaunt's return from Spain, Richard was able to rebuild his power, having Gloucester murdered in captivity in Calais. Warwick was stripped of his title. Bolingbroke and Mowbray were exiled.[107]

When John of Gaunt died in 1399, Richard disinherited Henry of Bolingbroke, who invaded England in response with a small force that quickly grew in numbers. Meeting little resistance, Henry deposed Richard to have himself crowned Henry IV of England. Richard died in captivity early the next year, probably murdered, bringing an end to the main Plantagenet line.[108]

House of Lancaster

Henry married his Plantagenet cousin Mary de Bohun who was descended from Edward I on her father's side and Edmund Crouchback on her mother's. This later Lancastrian branch was not prolific, although the couple had seven children, by 1471 all their few grandchildren were dead:[109]

- Edward of Lancaster, April 1382; buried Monmouth Castle, Monmouth

- Henry V (1386–1422)—had one son

- Henry VI of England (1421–1471)—also had one son

- Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales (1453–1471)

- Thomas, Duke of Clarence (1387–1421)— killed at the Battle of Baugé, one illegitimate son called John and also known as the bastard of Clarence

- John, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435)— had two childless marriages to Anne of Burgundy— daughter of John the Fearless— and Jacquetta of Luxembourg. John also had an illegitimate son called Richard and daughter called Mary.

- Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390–1447)—died under arrest for treason against Henry VI in suspicious circumstances but also possibly because of a stroke.

- Blanche of England (1392–1409) married in 1402 Louis III, Elector Palatine

- Philippa of England (1394–1430) married in 1406 Eric of Pomerania, King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

Henry asserted that his mother had legitimate rights through descent from Edmund Crouchback, whom he claimed was the elder son of Henry III of England, set aside due to deformity.[59] Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was the heir presumptive to Richard II by being the grandson of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence. As a child he was not considered a serious contender and he never showed interest in the throne. However, the later marriage of his granddaughter to Richard's son consolidated his descendants' claim to the throne with that of the more junior House of York.[59] Henry planned to resume war with France, but was plagued with financial problems, declining health and frequent rebellions.[110] He defeated a Scottish invasion, a serious rebellion by Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland in the North[110] and put down Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion in Wales.[111] Many saw it as a punishment from God when Henry was later struck down with leprosy and epilepsy.[112]

Henry IV died in 1413. His son and successor, Henry V of England, aware that Charles VI of France's mental illness had caused instability in France, invaded to assert the Plantagenet claims and won a near total victory over the French at the Battle of Agincourt.[113] In subsequent years Henry recaptured much of Normandy and successfully secured marriage to Catherine of Valois. The resulting Treaty of Troyes stated that Henry's heirs would inherit the throne of France. However, conflict continued with the Dauphin. When Henry died in 1422, he was succeeded by his nine-month-old son as Henry VI of England. The elderly Charles VI of France died two months later. French victory at the Battle of Patay enabled the Dauphin to be crowned at Reims.[114]

During the minority of Henry VI the war caused political division amongst the Plantagenets, Bedford, Humphrey of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Gloucester, and Cardinal Beaufort.[115] Humphrey's wife was accused of using witchcraft with the aim of putting him on the throne and Humphrey was later arrested and died in prison.[116] The refusal to renounce the Plantagenet claim to the French crown at the congress of Arras enabled the former Plantagenet ally Philip III, Duke of Burgundy, to reconcile with Charles, while giving Charles time to reorganise his feudal levies into a modern professional army.[117] Victory at the Battle of Castillon in 1453, brought an end to the war leaving only Calais as a continental possession.[118]

House of York

Edward III created his fourth son Edmund as the first duke of York in 1385. Edmund was married to Isabella, a daughter of King Peter of Castile and María de Padilla and the sister of Infanta Constance of Castile who was also the second wife of Edmund's brother, John of Gaunt. Both of Edmund's sons were killed in 1415. Richard became involved in the Southampton Plot. This was a conspiracy to depose Henry V in favour of Richard's brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer. When Mortimer revealed the plot to the king, Richard was executed for treason. Richard's childless older brother Edward was slain at the Battle of Agincourt later the same year. Constance of York was Edmund's only daughter and was also an ancestor of Queen Anne Neville. The increasingly interwoven Plantagenet relationships were demonstrated by Edmund's second marriage to Joan Holland. Her sister, Alianore Holland, was mother to Richard's wife Anne Mortimer. Margaret Holland, another of Joan's sisters, married John of Gaunt's son. She later married Thomas of Lancaster, John of Gaunt's grandson by King Henry IV. A third sister, Eleanor Holland, was mother-in-law to Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury—John's grandson by his daughter Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland. These sisters were all granddaughters of Joan of Kent, the mother of Richard II, and therefore Plantagenet descendants of Edward I.[119]

Edmund's son, Richard was married to Anne Mortimer who was the great-granddaughter of Edward III second surviving son—Lionel— the daughter of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and Eleanor Holland. Anne died giving birth to their only son in September 1411.[120] Richard's execution four years later left two orphans. Isabel who married into the Bourchier family and a son who was also called Richard. Although the Earl's title was forfeited, he was not attainted, and the four-year-old orphan Richard was his father's heir. Within months of his father's death, Richard's childless uncle, Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, was slain at the Battle of Agincourt. Richard was allowed to inherit the title of Duke of York in 1426. In 1432 he acquired the earldoms of March and Ulster following the death of his maternal uncle— Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March who had died campaigning with Henry V in France— and the earldom of Cambridge that been his fathers. Having descent from Edward III both in the maternal and paternal line made Richard a significant alternative claimant to the throne if the Lancastrian line failed and by Cognatic primogeniture arguably a superior claim.[121] A point he emphasised by—from 1148— being the first to assume the Plantagenet surname. Once he had inherited the March and Ulster titles he also became the wealthiest and most powerful noble in England, second only to the King himself. Richard married Cecily Neville who was a granddaughter of John of Gaunt and had thirteen or possible fifteen children.[122]

- Joan—(born 1438 died young).

- Anne, Duchess of Exeter. When Human remains thought to belong to the Richard III were found in 2012 it was from a descendant— Michael Ibsen— of her daughter from her second marriage—Anne St Leger, Baroness de Ros— that mitochondrial DNA was used in way of evidence for identification.[123]

- Henry—(born 1441, died young).

- Edward IV of England.

- Edmund, Earl of Rutland.

- Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk—married John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk and was the mother of a number of claimants to the throne.

- Margaret of York— married Charles the Bold.

- Two sons, William (born 1447, died young) and John(born 1448 died young).

- George, 1st Duke of Clarence.

- Thomas—(born 1450/51 died young).

- Richard III of England.

- Ursula—(born 1455, died young).

- Katherine and Humphrey are described by Cecily in her will as her children, but might in fact be her de la Pole grandchildren.

When Henry VI had a mental breakdown, Richard was named regent, but the birth of a male heir that resolved the succession question.[124] When Henry's sanity returned, the court party reasserted its authority. Richard of York and the Nevilles, defeated them at a skirmish called the First Battle of St Albans. The ruling class was deeply shocked and reconciliation was attempted.[125][126] York, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, and Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, fled abroad. The Nevilles returned to win the Battle of Northampton, where they captured Henry.[127] When Richard joined them, he surprised Parliament by claiming the throne, then forcing through the Act of Accord, which stated that Henry would remain as monarch for his lifetime, but would be succeeded by York. Margaret found this disregarding of her son's claims unacceptable and so the conflict continued. York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield and his head set on display at Micklegate Bar, along with those of Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, who had both been captured and beheaded.[128]

.jpg)

The Scottish queen Mary of Guelders provided Margaret with support and a Scottish army pillaged into southern England.[129] London resisted in the fear of being plundered, then enthusiastically welcomed York's son Edward, Earl of March, with Parliament confirming that Edward should be made king.[130] Edward was crowned after consolidating his position with victory at the Battle of Towton.[131]

Edward's preferment of the former Lancastrian-supporting Woodville family, following his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, led to Warwick and Clarence helping Margaret depose Edward and return Henry to the throne. Edward and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, fled, but on their return Clarence switched sides at the Battle of Barnet, leading to the death of the Neville brothers. The subsequent Battle of Tewkesbury brought the demise of the last of the male line of the Beauforts. The battlefield execution of Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, and later murder of Henry VI extinguished the House of Lancaster.

By the mid-1470s, the victorious House of York looked safely established, with seven living male princes. Edward and Elizabeth Woodville themselves had ten children, seven of whom survived him.[58]

- Elizabeth of York, queen consort to Henry VII of England (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503).

- Mary of York (11 August 1467 – 23 May 1482).

- Cecily of York (20 March 1469 – 24 August 1507); married first John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles and second Thomas Kyme or Keme.

- Edward V of England (4 November 1470 – c. 1483); briefly succeeded his father, as King Edward V of England. Was the elder of the Princes in the Tower.

- Margaret of York (10 April 1472 – 11 December 1472).

- Richard of Shrewsbury, 1st Duke of York (17 August 1473 – c. 1483). Was the younger of the Princes in the Tower.

- Anne of York (2 November 1475 – 23 November 1511); married Thomas Howard (later 3rd Duke of Norfolk).

- George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Bedford (March 1477 – March 1479).

- Catherine of York (14 August 1479 – 15 November 1527); married William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon.

- Bridget of York (10 November 1480 – 1517); became a nun.

However, dynastic infighting and misfortune quickly brought about the own demise of the House of York. George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, plotted against his brother and was executed. Following Edward's premature death in 1483, his brother Richard had Parliament declare Edward's two sons illegitimate on the pretext of an alleged prior pre-contract to Lady Eleanor Talbot, leaving Edward's marriage invalid.[132] Richard seized the throne and the Princes in the Tower were never seen again. Richard's son predeceased him and Richard was killed in 1485, following an invasion of foreign mercenaries led by Henry Tudor, who claimed the throne through his mother Margaret Beaufort. He assumed the throne as Henry VII, founding the Tudor dynasty and bringing the Plantagenet line of kings to an end.[58]

House of Tudor and other Plantagenet descendants

Tudor

At the time Henry Tudor seized the throne there were eighteen Plantagenet descendants who by notional modern standards could claim to have a stronger hereditary claim and by 1510 this number had been further increased by the birth of sixteen Yorkist children.[58] Henry mitigated this situation with his marriage to Elizabeth of York. She was the eldest daughter of Edward IV and all the couple's children were his cognatic heirs. Indeed Polydore Vergil noted Henry VIII pronounced resemblance to his grandfather, Edward: "For just as Edward was the most warmly thought of by the English people amongst all English kings, so this successor of his, Henry, was very like him in general appearance, in greatness of mind and generosity and for that reason was the most acclaimed and approved of all".[133]

This did not stop Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy—Edward's sister and Elizabeth's aunt— and members of the de le Pole family—children of Edward's sister and John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk— from frequent attempts to destabilise Henry's regime.[134] Henry imprisoned Margaret's nephew —Edward, Earl of Warwick, the son of her brother George— in the Tower of London but in 1487 Margaret financed a rebellion led by Lambert Simnel pretending to be Edward. John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln joined the revolt in the probable anticipation it would further his own ambitions to the throne but was killed in the suppression of the uprising at the Battle of Stoke Field in 1487.[135] Two further failed invasions supported by Margaret using Perkin Warbeck pretending to be Edward IV's son Richard of Shrewsbury and Warbeck's later escape implicated Warwick who was executed in 1499.

De La Pole

John de la Pole's attainder meant his brother Edmund inherited their father's titles but much of the wealth of the duchy of Suffolk was forfeit. Edmund did not possess sufficient finances to maintain his status as a duke so as a compromise he accepted the title of earl of Suffolk. Financial difficulties led to frequent legal conflicts and Edmund's indictment for murder in 1501. He fled with his brother Richard while their remaining brother William was imprisoned in the Tower—where he would remain until his death 37 years later—as part of a general suppression of Edmund's associates. In 1506 Archduke Philip returned Edmund and he was imprisoned in the Tower. In 1513, he was executed after Richard de la Pole was recognized by Louis XII of France as king of England claiming the English crown in his own right.[136] Richard— known as the White Rose— plotted an invasion of England for years. But serving in François I of France's invasion of Italy in 1525 was killed at the battle of Pavia fighting as the captain of the French landsknechts.[137]

Pole

Warwick's sister, and therefore Edward IV's niece, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury was executed by Henry VIII in 1541—but by this period the cause was more religious and political rather than dynastic. Richard III had asserted that her father Clarence's attainder barred his children from any claim to the throne and her marriage arranged by Henry VII to Sir Richard Pole was not auspicious. However, it did allow the couple to be closely involved in court affairs. Margaret's fortunes improved under Henry VIII and in February 1512 she was restored to the earldom of Salisbury and all of Warwicks's lands. This made her the first and, apart from Anne Boleyn, the only woman in sixteenth-century England to hold a peerage title in her own right.[138]

Her daughter, Ursula, married the son of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham. Buckingham's fall, arguments with the king over property and Margaret's open support for Katherine of Aragon and Princess Mary began the Pole's estrangement from the King. Hope of reconciliation was curtailed by the letter Reginald Pole. her son wrote to Henry VIII, De unitate, which declared his opposition to the royal supremacy. In 1538 her sons, Geoffrey Pole and Henry Pole, 1st Baron Montagu, Henry's wife, brother-in-law—Edward Neville — were arrested following the discovery that he had been in communication with Reginald, and the whole family was implicated in treason along with several friends and associates. With the exception of Sir Geoffrey Pole all the arrestees were beheaded. The King's cousin, Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter, was arrested along with his wife and 11-year old son (his wife would be released two years later while their son spent 15 years in the Tower until his release by Queen Mary I).[139]

Margaret was attaindered and the strategic position of her estates on the south coast, a perceived invasion threat in which Reginald was involved, and her embittered relationship with Henry VIII precluded any chance of pardon but the decision to execute her seems a spontaneous, rather than a premeditated, act. Her execution was botched at the hands of 'a wretched and blundering youth ... who literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner'. In 1886 she was beatified by Pope Leo XIII on the grounds she had laid down her life for the Holy See and for the truth of the orthodox Faith.[138]

Stafford

Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham combined multiple lines of Plantagenet descent: from Edward III by his son Thomas of Woodstock; from Edward III via two of his Beaufort children and from Edward I from Joan of Kent and the Holland family. His father failed in his rebellion against Richard III in 1483 but he was restored to his inheritance on the reversal of his father's attainder late in 1485. His mother married Henry VII's uncle—Jasper Tudor—and his wardship was entrusted to the king's mother—Lady Margaret Beaufort. In 1502 there was debate during Henry VII's illness whether Buckingham or Edmund de la Pole should act as regent for Henry VIII. There is no evidence of continuous hostility between Buckingham and Henry VIII but there is little doubt of the duke's dislike of Thomas Wolsey because he believed Wolsey was plotting to ruin the old nobility and Henry VIII instructed Wolsey to watch Buckingham, his brother—Henry Stafford, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, and three other peers. Neither Henry VIII or his father planned to destroy Buckingham because of his lineage and Henry VIII even allowed Buckingham's son and heir, Henry Stafford, 1st Baron Stafford, to marry Ursula Pole which gave the Stafford's a further line of royal blood descent. However, Buckingham was arrested in April 1521 and he was found guilty on 16 May, and executed the next day. Evidence was provided that the duke had been listening to prophecies that he would be king and that the Tudor family lay under God's curse for the execution of Warwick. This was said to explain Henry VIII's failure to produce a male heir. Much of this evidence consisted of ill-judged comments, speculation and bad temper but this added to the threat presented by Buckingham's descent.[140]

Tudor succession

As late as 1600 with the Tudor succession in doubt, older Plantagenet lines remained as possible claimants to a disputed throne, with religious and dynastic factors raising complications. Thomas Wilson wrote in a report The State of England, Anno Domini 1600 that there were 12 "competitors" for the succession. Wilson at the time of writing (about 1601) had been working on intelligence matters for Lord Buckhurst and Sir Robert Cecil.[141] His counting included five descendants of Henry VII and Elizabeth including the eventual successor James I of England but also seven from older Plantagenet lines:[142]

- Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon and George Hastings, 4th Earl of Huntingdon sons of Catherine Pole — daughter of Henry Pole who was grandson of Edward IV's brother George;

- Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland, from Elizabeth of Lancaster, Duchess of Exeter daughter of John of Gaunt;

- Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland from Mary of Lancaster, great-granddaughter of Henry III;

- António, Prior of Crato, son of Henry, King of Portugal and Ranuccio I Farnese, Duke of Parma, from Philippa of Lancaster, eldest daughter of John of Gaunt;

- Philip III of Spain and his daughter the infanta from Catherine of Lancaster, daughter to John of Gaunt, and from the Portugal family.

Ranulph Crewe illustrated, with regret, that by 1626 that the House of Plantagenet could not be considered to remain in existence in his noted speech during the Oxford Peerage case. The case was to rule on who should inherit the earldom of Oxford. It was referred by Charles I of England to the House of Lords, who called in the judges to their assistance. Crewe said:

I have labored to make a covenant with myself, that affection may not press upon judgment; for I suppose there is no man that hath any apprehension of gentry or nobleness, but his affection stands to the continuance of a house so illustrious, and would take hold of a twig or twine-thread to support it. And yet time hath his revolutions; there must be a period and an end to all temporal things—finis rerum—an end of names and dignities, and whatsoever is terrene; and why not of de Vere? For where is Bohun? Where is Mowbray[nb 1]? Where is Mortimer? Nay, which is more, and most of all, where is Plantagenet? They are entombed in the urns and sepulchres of mortality! yet let the name of de Vere stand so long as it pleaseth God.[143]

Further information

- This family tree includes selected members of the House of Plantagenet who were born legitimate.

Angevins Henry II of England, 1133–1189, had 5 sons;

- 1. William IX, Count of Poitiers, 1153–1156, died in infancy

- 2. Henry the Young King, 1155–1183, died without issue

- 3. Richard I of England, 1157–1199, died without legitimate issue

- 4. Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany, 1158–1186, had 1 son;

- A. Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, 1187–1203, died without issue

- 5. John of England, 1167–1216, had 2 sons;

Plantagenets

- A. Henry III of England, 1207–1272, had 6 sons;

- I. Edward I of England, 1239–1307, had 6 sons.

- a. John of England, 1266–1271, died young

- b. Henry of England, 1267–1274, died young

- c. Alphonso, Earl of Chester, 1273–1284, died young

- d. Edward II of England, 1284–1327, had 2 sons;

- i. Edward III of England, 1312–1377, had 8 sons;

- 1. Edward, the Black Prince, 1330–1376, had 2 sons;

- A. Edward, 1365–1372, died young

- B. Richard II of England, 1367–1400, died without issue

- 2. William of Hatfield, 1337–1337, died in infancy

- 3. Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, 1338–1368, 1 daughter.[144]

- A. Philippa, 5th Countess of Ulster, 1355–1381, married Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March, 2 sons and 2 daughters

- I Elizabeth Mortimer, 1371–1417 married Henry Percy (Hotspur), 1 son, 2 daughter

- To the Earls of Northumberland

- II Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, 1373–1398, married Eleanor daughter of Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent and Alice Holland, Countess of Kent granddaughter of Eleanor of Lancaster

- a. Anne de Mortimer, 1373–1399, married Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge (see below) and it is through her descent from Lionel that the House of York claimed precedence over the House of Lancaster.

- To the House of York

- b. Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, 1391–1425, heir presumptive to Richard II, no descendents

- I Elizabeth Mortimer, 1371–1417 married Henry Percy (Hotspur), 1 son, 2 daughter

- A. Philippa, 5th Countess of Ulster, 1355–1381, married Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March, 2 sons and 2 daughters

- 6. Thomas of England, 1347–1348, died in infancy

- 7. William of Windsor, 1348–1348, died in infancy

- 8. Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester, 1355–1397, had 1 son;

- A. Humphrey Plantagenet, 2nd Earl of Buckingham, 1381–1399, died without issue

- 1. Edward, the Black Prince, 1330–1376, had 2 sons;

- ii. John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall, 1316–1336, died without issue

- i. Edward III of England, 1312–1377, had 8 sons;

- e. Thomas of Brotherton, 1st Earl of Norfolk, 1300–1338, had 2 sons;

- i. Edward of Norfolk, 1320–1334, died young

- ii. John Plantagenet, 1328–1362, died without issue

- f. Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent, 1301–1330, had 2 sons;

- i. Edmund Plantagenet, 2nd Earl of Kent, 1326–1331, died young

- ii. John Plantagenet, 3rd Earl of Kent, 1330–1352, died without issue

- II. Edmund Crouchback, 1st Earl of Lancaster, 1245–1296, had 3 sons;

- a. Thomas Plantagenet, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 1278–1322, died without issue

- b. Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, 1281–1345, had 1 son;

- i. Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361, died without male issue, 2 daughters

- Maud, Countess of Leicester, 1339–1362, died without issue

- Blanche of Lancaster, married John of Gaunt and had 1 son and two daughters

- To House of Lancaster

- i. Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361, died without male issue, 2 daughters

- c. John of Beaufort, Lord of Beaufort, 1286–1327, died without issue

- III. Richard of England, 1247–1256, died young

- IV. John of England, 1250–1256, died young

- V. William of England, 1251–1256, died young

- VI. Henry of England, 1256–1257, died young

- I. Edward I of England, 1239–1307, had 6 sons.

- B. Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, 1209–1272, had 5 sons;

- I. John of Cornwall, 1232–1233, died in infancy

- II. Henry of Almain, 1235–1271, died without issue

- III. Nicholas of Cornwall, 1240–1240, died in infancy

- IV. Richard of Cornwall, 1246–1246, died in infancy

- V. Edmund, 2nd Earl of Cornwall, 1249–1300, died without issue

- A. Henry III of England, 1207–1272, had 6 sons;

House of Lancaster

- 4. John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, 1340–1399, had 4 sons;

- A. John of Lancaster, 1362–1365, died in infancy

- B. Edward Plantagenet, 1365–1368, died in infancy

- C. John Plantagenet, 1366–1367, died in infancy

- D. Henry IV of England, 1366–1413, had 5 sons;

- I. Edward Plantagenet, 1382–1382, died in infancy

- II. Henry V of England, 1387–1422, had 1 son;

- a. Henry VI of England, 1421–1471, had 1 son;

- i. Edward of Westminster, 1453–1471, died without issue

- a. Henry VI of England, 1421–1471, had 1 son;

- III. Thomas, Duke of Clarence, 1388–1421, died without issue

- IV. John, Duke of Bedford, 1389–1435, died without issue

- V. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, 1390–1447, died without male issue

- E. John, 1374–1375, died in infancy

- 4. John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, 1340–1399, had 4 sons;

House of Beaufort (illegitimate branch of House of Lancaster)

- F. John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, 1373–1410, illegitimate, had 4 sons;

- I. Henry Beaufort, 2nd Earl of Somerset, 1401–1418, died without issue

- II. John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1403–1444, died without male issue

- a. Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby 1430–1509, married Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, 1 son

- i. Henry VII of England married Elizabeth of York

- To the House of Tudor

- a. Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby 1430–1509, married Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, 1 son

- III. Thomas Beaufort, Count of Perche, 1405–1431, died without issue

- IV. Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, 1406–1455, had 4 sons;

- a. Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset, 1436–1464, had 1 son;

- i. Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester,1460–1526, had 1 son;

- 1. Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester, 1496–1549, had 4 sons;

- A. William Somerset, 3rd Earl of Worcester, 1526–1589, had 1 son;

- I. Edward Somerset, 4th Earl of Worcester, 1568– 1628, had 8 sons;

- B. Francis Somerset

- C. Charles Somerset

- D. Thomas Somerset

- A. William Somerset, 3rd Earl of Worcester, 1526–1589, had 1 son;

- 1. Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester, 1496–1549, had 4 sons;

- i. Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester,1460–1526, had 1 son;

- b. Edmund Beaufort, 4th Duke of Somerset, 1439–1471, died without issue

- c. John Beaufort, Earl of Dorset, 1455–1471, died without issue

- g. Thomas Beaufort, 1455–1463, died young

- a. Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset, 1436–1464, had 1 son;

- G. Cardinal Henry Beaufort Bishop of Winchester, 1375–1447, died without issue

- H. Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter, 1377–1427, had 1 son;

- I. Henry Beaufort, died young

- F. John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, 1373–1410, illegitimate, had 4 sons;

House of York

- 5. Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, 1341–1402, had 2 sons;

- A. Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, 1373–1415, died without issue

- B. Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, 1375–1415, had 1 son;

- I. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, 1411–1460, had 8 sons;

- a. Henry of York, 1441–1441, died in infancy

- b. Edward IV of England, 1442–1483, had 3 sons and 7 daughters;

- i. Edward V of England, 1470–?, died without issue

- ii. Richard of Shrewsbury, 1st Duke of York, 1473–?, died without issue

- iii. George Plantagenet, Duke of Bedford, 1477–1479, died young

- iv. Elizabeth of York married Henry VII of England, 4 sons and 4 daughters

- To the House of Tudor

- c. Edmund, Earl of Rutland, 1443–1460, died without issue

- d. William of York, 1447–1447, died in infancy

- e. John of York, 1448–1448, died in infancy

- f. George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, 1449–1478, had 2 sons and 2 daughters;

- i. Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, 1475–1499, died without issue

- ii. Richard of York, 1476–1477, died in infancy

- iii. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, 1473–1541, considered by some to be the last of the Plantagenets, had 4 sons and one daughter, considered the source of one of the Alternative successions of the English crown.

- g. Thomas of York, 1451–1451, died in infancy

- h. Richard III of England, 1452–1485, had 1 son;

- i. Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales, 1473–1484, died young

- I. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, 1411–1460, had 8 sons;

- 5. Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, 1341–1402, had 2 sons;

| Title | Held | Designation and details |

|---|---|---|

| Count of Anjou | 870–1204 | ancestral family title, originating with Ingelger. Remained under direct control of the Plantagenets until Philip II of France captured the county and merged it with the House of Capet royal holdings. |

| Count of Maine | 1110–1203 | ancestral family title, inherited by the House of Anjou after the marriage of Ermengarde of Maine with Fulk V of Anjou. It was captured and merged into the House of Capet royal holdings. |

| King of Jerusalem | 1131–1143 | title held by the grandfather of Henry II of England named Fulk of Jerusalem. Ruled for a while by their cousins. The Plantagenets followed up their claim in the Third and Ninth Crusades but never regained it. |

| Duke of Normandy | 1144–1485 | also used Count of Mortain title. Due to be handed to the Plantagenets during the Anarchy but Geoffrey V of Anjou conquered it early. Mainland holdings lost to Valois in 1259, but title continued to be used in relation to Channel Islands. Eventually lost to House of Tudor. |

| Duke of Aquitaine | 1152–1422 | titles Duke of Gascony and Count of Poitiers also used. The Duchy became part of the Plantagenet holdings after Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry II. Eventually lost to House of Valois. |

| King of England | 1154–1485 | title became part of the Plantagenet holdings after the Treaty of Wallingford. The title was inherited through Matilda, Lady of the English. Eventually lost to the House of Tudor. |

| Lord of Ireland | 1177–1485 | title was a Plantagenet holding since 1177, replacing the High Kings of Ireland title. Eventually lost to the Tudors; Henry VIII of England later raised the Lordship to a Monarchal title. |

| Duke of Brittany | 1181–1203 | title Count of Nantes also used. Became Plantagenet title after marriage of Constance, Duchess of Brittany, and Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany. Strongly linked to Earl of Richmond title. |

| Lord of Cyprus | 1191–1192 | title was briefly held by Richard the Lionheart after his conquest of the island, he then sold the island to Guy of Lusignan who raised Cyprus from a Lordship into the Kingdom of Cyprus. |

| King of Sicily | 1254–1263 | titular claim rather than de facto. Pope Alexander IV had declared Sicily a papal possession and offered the crown to Henry III's son Edmund, Earl of Lancaster. The next Pope reversed the offer and the Plantagenets never succeeded in taking the kingdom, but took the claim seriously. |

| King of Germany and King of the Romans | 1257–1272 | Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, was elected king in opposition to the claim of Alfonso X of Castile, and after extensive lobbying and bribery. He was crowned in 1257 at Aachen as King of Germany. As such, he could claim the title of King of the Romans as emperor-elect. Since the pope supported Alfonso, he never crowned Richard as emperor. Richard only made four brief visits to Germany, and his sons were not considered as possible successors. |

| Prince of Wales | 1301–1484 | Originally a fief of the Angevin Empire, it was given to the first-born son of the King of England after the Aberffraw dynasty rebelled against their vassal. Eventually lost to the Tudors. |

| King of France | 1340–1485 | Mostly titular, rather than de facto. The Plantagenets claimed to be the senior continuation of the House of Capet after the Direct Capetians line came to an end. During part of the Lancastrian period of rule there was a time when this was de facto rulership. |

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with predecessor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry II of England (Henry Curtmantle) | 19 December 1154 | 6 July 1189 | son of Empress Matilda, heir to the English throne but was usurped by his cousin, Stephen I of England. |