Hosius of Corduba

Hosius of Corduba (c. 256 – 359), also known as Osius or Ossius, was a bishop of Cordova and an important and prominent advocate for Catholic Christianity in the Arian controversy which divided the 4th century early Christian Church. He suggested, and possibly presided at the Council of Nicaea and also presided at the Council of Sardica.[1] After Lactantius, he was the closest Christian advisor to the Emperor Constantine and guided the content of public utterances, such as Constantine's Oration to the Saints, addressed to the assembled bishops.[2]

Life

He was probably born in Roman Corduba (as it was then known) in Hispania,[3][4][5] although a passage in Zosimus has sometimes been conjectured as the writer's belief that Hosius was a native of Egypt.

Elected to the see of Cordova about 295, he narrowly escaped martyrdom in the persecution of Maximian. In 300 or 301 he attended the provincial Council of Elvira[6] (his name appearing second in the list of those present), and upheld its severe canons concerning such points of discipline as questions concerning clerical marriage, and the treatment of those who had abjured their faith during the recent persecutions. The Council appears to have had Novationist tendencies and held a strict view that refused readmission to those baptized Christians who had denied their faith or performed the formalities of a ritual sacrifice to the pagan gods under pressures of persecution.[7]

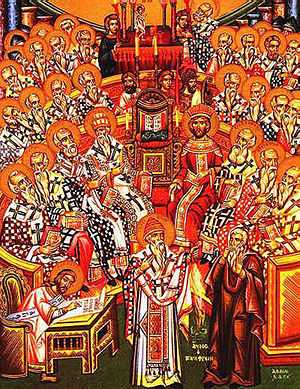

In 313 he appears at the court of Constantine, being expressly mentioned by name in a constitution directed by the emperor to Caecilianus of Carthage in that year. He is not listed among the attendees of the Council of Arles of 314, but may have been in attendance upon the emperor, who was engaged in his first war with Licinius in Pannonia.[7] As early as 320 or 321 Alexander, Bishop of Alexandria, convoked a council at Alexandria at which more than one hundred bishops from Egypt and Libya anathematized Arius, his deacon.[2] In 323 Hosius was the bearer of Constantine's letter to Bishop Alexander and Arius, in which he urged them to reconciliation. On the failure of the negotiations in Egypt, Constantine conveyed the Council of Nicaea, probably in agreement with Pope Sylvester I, and perhaps on the advise of Hosius. Hosius presided, although it is unclear whether he did so in the name of the pope or was nominated by Constantine. Hosius took an active part in drawing up its canons and the Nicene Creed. After the Council, Hosius returned to his diocese in Spain.[6]

For nearly 50 years Hosius was the foremost bishop of his time. He was held in universal esteem and exercised great influence.[7] In 340 Athanasius of Alexandria was expelled from his diocese by the Arians. After passing three years in Rome, Athanasius went into Gaul to confer with Hosius. From there, they went to the Council of Sardica, which began in the summer, or, at latest, in the autumn of 343. Hosius presided, proposed the canons, and was the first to sign the Acts of the council.[6]

After Constantine's death, the prestige given to the orthodox cause in the Arianist controversy by the support of the venerable Hosius led the Arians to bring pressure to bear upon Constantius II, who had him summoned to Milan where he declined to condemn Athanasius nor to extend communion to Arians. He so impressed the emperor that he was authorized to return home. More Arian pressure led to Constantius writing a letter demanding whether he alone was going to remain obstinate. In reply, Hosius sent his courageous letter of protest against imperial interference in Church affairs (353), preserved by Athanasius[8] which led to Hosius' exile in 355 to Sirmium, an imperial center in Pannonia (in modern Serbia). From his exile he wrote to Constantius II his only extant composition, a letter justly characterized by the French historian Sebastian Tillemont as displaying gravity, dignity, gentleness, wisdom, generosity and in fact all the qualities of a great soul and a great bishop.

Subjected to continual pressure from the Arians the old man, who was near his hundredth year, was weak enough to sign the formula adopted by the third Council of Sirmium in 357,[9] which involved communion with the Arians but not the condemnation of Athanasius. He was then permitted to return to his Hispanic diocese, where he died in 359.

There is a letter from Pope Liberius to him (ca. 353).

References

- ↑ Jurgens, W.A., The Faith of the Early Fathers: Pre-Nicene and Nicene eras. p. 280, (Liturgical Press, 1970)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Leclercq, Henri. "The First Council of Nicaea." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 8 Dec. 2014

- ↑ Dudley, Dean. The History of the First Council of Nice: A Worlds Christian Convention, A. D. 325 with a Life of Constantine, p.49, (Cosimo, Inc., 2007)

- ↑ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, Volume 3 (Library of Alexandria, 1966)

- ↑ Payne, Robert. The Holy Fire: The Story of the Fathers of the Eastern Church, p.79, (St Vladimir's Seminary Press 1980)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Myers, Edward. "Hosius of Cordova." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 8 Dec. 2014

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Wace, Henry. "Hosius", A Dictionary of Early Christian Biography, John Murray, London, 1911

- ↑ Athanasius, Historia Arianorum, 42-45.

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, iv.3.

Further reading

- V. C. de Clercq, Ossius of Cordova. A contribution to the history of the Constantinian period (Washington, 1954).

- Sebastien Tillemont, Mémoires, VII. 300-321 (1700)

- Hefele, Conciliengeschichte, vol. i.

- H. M. Gwatkin, Studies of Arianism (Cambridge, 1882, 2nd ed., 1900)

- A. W. W. Dale, The Synod of Elvira (London, 1882)

- article s.v. in Herzog-Hauck, Realencyklopädie (3rd ed., 1900), with bibliography.

- Catholic Encyclopedia