Hopf lemma

In mathematics, the Hopf lemma, named after Eberhard Hopf, states that if a continuous real-valued function in a domain in Euclidean space with sufficiently smooth boundary is harmonic in the interior and the value of the function at a point on the boundary is greater than the values at nearby points inside the domain, then the derivative of the function in the direction of the outward pointing normal is strictly positive. The lemma is an important tool in the proof of the maximum principle and in the theory of partial differential equations. The Hopf lemma has been generalized to describe the behavior of the solution to an elliptic problem as it approaches a point on the boundary where its maximum is attained.

Statement for harmonic functions

Let Ω be a bounded domain in Rn with smooth boundary. Let f be a real-valued function continuous on the closure of Ω and harmonic on Ω. If x is a boundary point such that f(x) > f(y) for all y in Ω sufficiently close to x, then the (one-sided) directional derivative of f in the direction of the outward pointing normal to the boundary at x is strictly positive.

Proof for harmonic functions

Subtracting a constant, it can be assumed that f(x) = 0 and f is strictly negative at interior points near x. Since the boundary of Ω is smooth there is a small ball contained in Ω the closure of which is tangent to the boundary at x and intersects the boundary only at x. It is then sufficient to check the result with Ω replaced by this ball. Scaling and translating, it is enough to check the result for the unit ball in Rn, assuming f(x) is zero for some unit vector x and f(y) < 0 if |y| < 1.

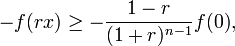

By Harnack's inequality applied to −f

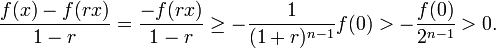

for r < 1. Hence

Hence the directional derivative at x is bounded below by the strictly positive constant on the right hand side.

General discussion

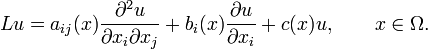

Consider a second order, uniformly elliptic operator of the form

Here  is an open, bounded subset of

is an open, bounded subset of  .

.

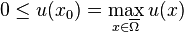

The Weak Maximum Principle states that a solution of the equation  in

in  attains its maximum value on the closure

attains its maximum value on the closure  at some point on the boundary

at some point on the boundary  . Let

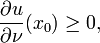

. Let  be such a point, then necessarily

be such a point, then necessarily

where  denotes the outer normal derivative. This is simply a consequence of the fact that

denotes the outer normal derivative. This is simply a consequence of the fact that  must be nondecreasing as

must be nondecreasing as  approach

approach  . The Hopf Lemma strengthens this observation by proving that, under mild assumptions on

. The Hopf Lemma strengthens this observation by proving that, under mild assumptions on  and

and  , we have

, we have

A precise statement of the Lemma is as follows. Suppose that  is a bounded region in

is a bounded region in  and let

and let  be the operator described above. Let

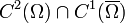

be the operator described above. Let  be of class

be of class  and satisfy the differential inequality

and satisfy the differential inequality

Let  be given so that

be given so that  .

If (i)

.

If (i)  is

is  at

at  , and (ii)

, and (ii)  , then either

, then either  is a constant, or

is a constant, or  , where

, where  is the outward pointing unit normal, as above.

is the outward pointing unit normal, as above.

The above result can be generalized in several respects. The regularity assumption on  can be replaced with an interior ball condition: the lemma holds provided that there exists an open ball

can be replaced with an interior ball condition: the lemma holds provided that there exists an open ball  with

with  . It is also possible to consider functions

. It is also possible to consider functions  that take positive values, provided that

that take positive values, provided that  . For the proof and other discussion, see the references below.

. For the proof and other discussion, see the references below.

See also

References

- Evans, Lawrence (2000), Partial Differential Equations, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-0772-2

- Fraenkel, L. E. (2000), An Introduction to Maximum Principles and Symmetry in Elliptic Problems, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-461955

- Krantz, Steven G. (2005), Geometric Function Theory: Explorations in Complex Analysis, Springer, pp. 127–128, ISBN 0817643397

- Taylor, Michael E. (2011), Partial differential equations I. Basic theory, Applied Mathematical Sciences 115 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 9781441970541 (The Hopf lemma is referred to as "Zaremba's principle" by Taylor.)