Homotherium

| Homotherium Temporal range: Early Pliocene to Late Pleistocene, 5–0.01Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Skeleton of H. serum from Friesenhahn cave, Texas Memorial Museum, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | †Machairodontinae |

| Tribe: | †Homotherini |

| Genus: | †Homotherium Fabrini, 1890 |

| Species | |

|

†Homotherium aethiopicum | |

Homotherium is an extinct genus of machairodontine saber-toothed cats, often termed scimitar-toothed cats, that ranged from North America, South America, Eurasia, and Africa during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs (5 mya–10,000 years ago), existing for approximately 5 million years.[1]

It first became extinct in Africa some 1.5 million years ago. In Eurasia it survived until about 30,000 years ago.[2] In South America it is only known from a few remains in the northern region (Venezuela), from the mid-Pleistocene.[3]The last scimitar cat could have survived in North America until 10,000 years ago.

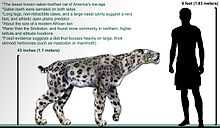

Anatomy

Homotherium reached 1.1 m (3.6 ft) at the shoulder and weighed an estimated 150–225 kg (331–496 lb) and was therefore about the size of a male African lion.[4][5][6] Compared to some other machairodonts, like Smilodon or Megantereon, Homotherium had shorter upper canines, but they were flat, serrated and longer than those of any living cat. Incisors and lower canines formed a powerful puncturing and gripping device. Among living cats, only the tiger (Panthera tigris) has such large incisors, which aid in lifting and carrying prey. The molars of Homotherium were rather weak and not adapted for bone crushing. The skull was longer than in Smilodon and had a well-developed crest, where muscles were attached to power the lower jaw. This jaw had down-turned forward flanges to protect the scimitars. Its large canine teeth were crenulated and designed for slashing rather than purely stabbing.

It had the general appearance of a cat, but some of its physical characteristics are rather unusual for a large cat. The limb proportions of Homotherium gave it a hyena-like appearance. The forelegs were elongated, while the hind quarters were rather squat with feet perhaps partially plantigrade, causing the back to slope towards the short tail. Features of the hind limbs indicate that this cat was moderately capable of leaping. The pelvic region, including the sacral vertebrae, was bear-like, as was the short tail composed of 13 vertebrae—about half the number of long-tailed cats.

The unusually large, square nasal opening, like that of the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), presumably allowed quicker oxygen intake, which aided in rapid running and in cooling the brain. As in the cheetah, too, the brain's visual cortex was large and complex, emphasizing the scimitar cat's ability to see well and function in the day, rather than the night as do most other cats.

Range and species

Homotherium probably derived from Machairodus and appeared for the first time at the Miocene-Pliocene border, about 5 million years ago.[7] During the Pleistocene it occurred in vast parts of Eurasia, North America and until the middle Pleistocene (about 1.5 million years ago) even in Africa. A fossil of H. crenatidens was inadvertently dredged from the bed of the North Sea, which was a flat, low-lying extent of marshy tundra laced with rivers during the recent glaciation.[8] There has also been a discovery of 1.8 million-year-old fossils in Venezuela,[9][10] indicating that scimitar cats were able to invade South America along with Smilodon during the Great American Interchange. These remains form the holotype of Homotherium venezuelensis.[3] How long they lasted in South America is not yet evident. Homotherium survived in Eurasia and North America until about 30 000[2] and 10 000 years ago, respectively.

Several species (H. nestianus, sainzelli, crenatidens, nihowanensis, ultimum) are recognized from Eurasia, which differ mainly in the shape of the canines and in body size. But given the fluctuation range of the size of modern large cats, it is highly probable that all belong to one species, Homotherium latidens.

Two species described form the early Pleistocene of Africa are Homotherium ethiopicum and Homotherium hadarensis. But they also hardly differ from the Eurasian forms.[7] On the African continent the genus disappeared about 1.5 million years ago. In North America, a very similar species, Homotherium serum occurred from the late Pliocene until the late Pleistocene. Remains have been found at various sites between Alaska and Texas. In the southern parts of its range the American Homotherium co-existed with Smilodon; in the northern parts it was the only species of saber-toothed cat. The American Homotherium was originally described by the name Dinobastis.

Despite Homotherium's vast range and the large amount of fossil remains from Eurasia, Africa and North America, complete skeletons of this cat are relatively rare. One of the most famous sites of Homotherium remains is Friesenhahn cave in Texas, where 30 Homotherium skeletons were found, along with hundreds of juvenile mammoths and several dire wolves.[11]

Diet and habitat

The decline of Homotherium could be a result of the disappearance of large herbivorous mammals like mammoths in America at the end of the Pleistocene. In North America fossil remains of Homotherium are less abundant than those of its contemporary Smilodon. For the most part it probably inhabited higher latitudes and altitudes and therefore was likely to be well adapted to the colder conditions of the mammoth steppe environment. Reduced claws, relatively slender limbs and the sloping back indicate adaptations for endurance running in open habitats.[12]

References

- A. Turner: The big cats and their fossil relatives. Columbia University Press, 1997.ISBN 0-231-10229-1

- ↑ PaleoBiology Database: Homotherium, basic info

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Reumer, J.W.F.; L. Rook; K. Van Der Borg; K. Post; D. Mol; J. De Vos (2003). "Late Pleistocene survival of the saber-toothed cat Homotherium in northwestern Europe". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23: 260. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[260:LPSOTS]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rincón, A., Prevosti, F., & Parra, G. (2011). New saber-toothed cat records (Felidae: Machairodontinae) for the Pleistocene of Venezuela, and the Great American Biotic Interchange Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 31 (2), 468-478 DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2011.550366

- ↑ http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/mesozoicmammals/p/homotherium.htm

- ↑ Meade, G.E. 1961: The saber-toothed cat Dinobastis serus. Bulletin of the Texas Memorial Museum 2(II), 23–60.

- ↑

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Alan Turner: "The Evolution of the guild of larger terrestrial carnivores during the Plio-Pleistocene in Africa". Geobios, no 23, fasc. 3, p. 349-368, 1990.

- ↑ (BBC News) Paul Rincon, "Big cat fossil found in North Sea", 18 November 2008 accessed 18 November 2008

- ↑ Sanchez, Fabiola (2008-08-22). "Saber-toothed Cat Fossils Discovered in Venezuela". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ Orozco, José (2008-08-22). "Sabertooth Cousin Found in Venezuela Tar Pit -- A First". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ Rawn-Schatzinger, V. (1992). "The scimitar cat Homotherium serum (Cope)". Report of Investigations (Illinois State Museum) (47): pp. 1–80.

- ↑ M. Anton et al.: Co-existence of scimitar-toothed cats, lions and hominins in the European Pleistocene. Implications of the post-cranial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Owen) for comparative palaeoecology. Quaternary Science Reviews 24 (2004).

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Homotherium |