Homo erectus

| Homo erectus Temporal range: 1.9–0.007Ma Early Pleistocene – Middle Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of a specimen from Tautavel, France | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. erectus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo erectus (Dubois, 1892) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Homo erectus (meaning "upright man," from the Latin ērigere, "to put up, set upright") is an extinct species of hominin that lived throughout most of the Pleistocene, with the earliest first fossil evidence dating to around 1.9 million years ago and the most recent to around 70,000 years ago (with extinction linked to the Toba catastrophe theory). It is assumed that the species originated in Africa and spread as far as Georgia, India, Sri Lanka, China and Java.[1][2]

There is still disagreement on the subject of the classification, ancestry, and progeny of H. erectus, with two major alternative classifications: erectus may be another name for Homo ergaster, and therefore the direct ancestor of later hominids such as Homo heidelbergensis, Homo neanderthalensis, and Homo sapiens; or it may be an Asian species distinct from African ergaster.[1][3][4]

Some palaeoanthropologists consider H. ergaster to be simply the African variety of H. erectus. This leads to the use of the term "Homo erectus sensu stricto" for the Asian H. erectus, and "Homo erectus sensu lato" for the larger species comprising both the early African populations (H. ergaster) and the Asian populations.[5][6]

A new debate appeared in 2013 in the paleontological community, with the publication of the Dmanisi skull 5 (D4500).[7] Considering the large morphological variation between all Dmanisi skulls, researchers suggest that many examples of early human ancestors previously classified as Homo ergaster or Homo heidelbergensis and even more, Homo habilis, were actually all Homo erectus.[8][9]

Origin

The first hypothesis is that H. erectus migrated from Africa during the Early Pleistocene, possibly as a result of the operation of the Saharan pump, around 2.0 million years ago, and it dispersed throughout much of the Old World. Fossilized remains 1.8 to 1 million years old have been found in Africa (e.g., Lake Turkana[10] and Olduvai Gorge), Georgia, Indonesia (e.g., Sangiran in Central Java and Trinil in East Java), Vietnam, China (e.g., Shaanxi) and India.[11]

The second hypothesis is that H. erectus evolved in Eurasia and then migrated to Africa. The species occupied a Caucasus site called Dmanisi, in Georgia, from 1.85 million to 1.77 million years ago, at the same time or slightly before the earliest evidence in Africa. Excavations found 73 stone tools for cutting and chopping and 34 bone fragments from unidentified creatures.[12][13]

Discovery and representative fossils

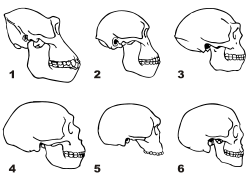

1. Gorilla 2. Australopithecus 3. Homo erectus 4. Neanderthal (La Chapelle aux Saints) 5. Steinheim Skull 6. Modern Homo sapiens

The Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois, who was especially fascinated by Darwin's theory of evolution as applied to man, set out to Asia (the place accepted then, despite Darwin, as the cradle of human evolution – see Haeckel § Research), to find a human ancestor in 1886. In 1891, his team discovered a human fossil on the island of Java, Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia); he described the species as Pithecanthropus erectus (from the Greek πίθηκος,[14] "ape", and ἄνθρωπος,[15] "man"), based on a calotte (skullcap) and a femur like that of H. sapiens found from the bank of the Solo River at Trinil, in East Java. (This species is now regarded as H. erectus).

The find became known as Java Man. Thanks to Canadian anatomist Davidson Black's (1921) initial description of a lower molar, which was dubbed Sinanthropus pekinensis,[16] however, most of the early and spectacular discoveries of this taxon took place at Zhoukoudian in China. German anatomist Franz Weidenreich provided much of the detailed description of this material in several monographs published in the journal Palaeontologica Sinica (Series D).

Nearly all of the original specimens were lost during World War II; however, authentic Weidenreichian casts do exist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, and are considered to be reliable evidence.

Throughout much of the 20th century, anthropologists debated the role of H. erectus in human evolution. Early in the century, however, due to discoveries on Java and at Zhoukoudian, it was believed that modern humans first evolved in Asia. A few naturalists—Charles Darwin most prominent among them—believed that humans' earliest ancestors were African: Darwin pointed out that chimpanzees and gorillas, who are human relatives, live only in Africa.[17]

From the 1950s to 1970s numerous fossil finds from East Africa confirmed this hypothesis, offering evidence that the oldest hominins originated there. It is now believed that H. erectus is a descendant of earlier genera such as Ardipithecus and Australopithecus, or early Homo-species such as H. habilis or H. ergaster. H. habilis and H. erectus coexisted for several thousand years, and may represent separate lineages of a common ancestor.[18]

Archaeologist John T. Robinson and Robert Broom named Telanthropus capensis in the 1950s, now thought to belong to Homo erectus.[19] Robinson discovered a jaw fragment, SK 45, in September 1949 in Swartkrans, South Africa. In 1957, Simonetta proposed to re-designate it Homo erectus, and Robinson (1961) agreed.[20]

The skull of Tchadanthropus uxoris, discovered in 1961 by Yves Coppens in Chad, is the earliest fossil human discovered in the North of Africa.[21] This fossil "had been so eroded by wind-blown sand that it mimicked the appearance of an australopith, a primitive type of hominid".[22] Though some first considered it to be a specimen of H. habilis,[23] it is no longer considered to be a valid taxon, and scholars rather consider it to represent H. erectus.[21][24]

Homo erectus georgicus

Homo erectus georgicus is the subspecies name sometimes used to describe fossil skulls and jaws found in Dmanisi, Georgia. Although first proposed as a separate species, it is now classified within H. erectus.[25][26][27] 5 skulls where discovered between 1991 and 2005 (D2700, D3444 and a complete skull in 2005 the D4500). The fossils are about 1.8 million years old. The remains were first discovered in 1991 by Georgian scientist, David Lordkipanidze, accompanied by an international team that unearthed the remains. There have been many proposed explanations of the dispersion of H. erectus georgicus.[28] Implements and animal bones were found alongside the ancient human remains.

At first, scientists thought they had found mandibles and skulls belonging to Homo ergaster, but size differences led them to name a new species, Homo georgicus, which was posited as a descendant of Homo habilis and ancestor of Asian Homo erectus. This classification was not upheld, and the fossil is now considered a divergent subgroup of Homo erectus, sometimes called Homo erectus georgicus.[29][30][31][32]

At around 600 cubic centimetres (37 cu in) brain volume, the skull D2700 is dated to 1.77 million years old and in good condition, offering insights in comparison to the modern human cranial morphology. At the time of discovery the cranium was the smallest and most primitive Hominina skull from the pleistocene period. Now its brother Skull 5 published much later, (2013) has this honor.

Subsequently, four fossil skeletons were found, showing a species primitive in its skull and upper body but with relatively advanced spines and lower limbs, providing greater mobility. They are now thought not to be a separate species, but to represent a stage soon after the transition between Homo habilis and H. erectus, and have been dated at 1.8 million years before the present, according to the leader of the project, David Lordkipanidze.[26][33] The assemblage includes one of the largest Pleistocene Homo mandibles (D2600), one of the smallest Lower Pleistocene mandibles (D211), a nearly complete sub‐adult (D2735), and a completely toothless specimen D3444/D3900.[34]

A further skull name D4500 or simply Skull 5, the only intact skull ever found of an early Pleistocene hominin, was described in 2013.[8] At just under 546 cubic centimetres, the skull had the smallest braincase of all the individuals found at the site. The variations in these skulls prompted the researchers to examine variations in modern human and chimpanzees. The researchers found that while the Dmanisi skulls looked different from one another, the variations were no greater than those seen among modern people and among chimpanzees. These variations therefore suggest that previous fossil finds thought to be of different species on the basis of their variations, such as Homo rudolfensis, Homo gautengensis, H. ergaster and potentially H. habilis, may be alternatively interpreted as belonging to the same lineage as Homo erectus.[35]

Classification and special distinction

Many paleoanthropologists still debate the definition of H. erectus and H. ergaster as separate species. Several scholars suggested dropping the taxon Homo erectus and instead equating H. erectus with the archaic H. sapiens.[36][37][38][39] Some call H. ergaster the direct African ancestor of H. erectus, proposing that it emigrated out of Africa and immigrated to Asia, branching into a distinct species.[40] Most dispense with the species name ergaster, making no distinction between such fossils as the Turkana Boy and Peking Man. Although "Homo ergaster" has gained some acceptance as a valid taxon, these two are still usually defined as distinct African and Asian populations of the larger species H. erectus.

While some have argued (and insisted) that Ernst Mayr's biological species definition cannot be used here to test the above hypotheses, one can, however, examine the amount of morphological cranial variation within known H. erectus / H. ergaster specimens, and compare it to what one sees in disparate extant groups of primates with similar geographical distribution or close evolutionary relationship. Thus, if the amount of variation between H. erectus and H. ergaster is greater than what one sees within a species of, say, macaques, then H. erectus and H. ergaster may be considered two different species.

The extant model of comparison is very important, and selecting appropriate species can be difficult. (For example, the morphological variation among the global population of H. sapiens is small,[41] and our own special diversity may not be a trustworthy comparison). As an example, fossils found in Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia were originally described as belonging to another closely related species, Homo georgicus, but subsequent examples showed their variation to be within the range of Homo erectus, and they are now classified as Homo erectus georgicus.

H. erectus had a cranial capacity greater than that of Homo habilis (although the Dmanisi specimens have distinctively small crania): the earliest remains show a cranial capacity of 850 cm³, while the latest Javan specimens measure up to 1100 cm³,[41] overlapping that of H. sapiens.; the frontal bone is less sloped and the dental arcade smaller than the australopithecines'; the face is more orthognatic (less protrusive) than either the australopithecines' or H. habilis's, with large brow-ridges and less prominent zygomata (cheekbones). These early hominins stood about 1.79 m (5 ft 10 in),[42] (Only 17 percent of modern male humans are taller)[43] and were extraordinarily slender, with long arms and legs.[44]

The sexual dimorphism between males and females was slightly greater than seen in H. sapiens, with males being about 25% larger than females, but less than that of the earlier Australopithecus genus. The discovery of the skeleton KNM-WT 15000, "Turkana boy" (Homo ergaster), made near Lake Turkana, Kenya by Richard Leakey and Kamoya Kimeu in 1984, is one of the most complete hominid-skeletons discovered, and has contributed greatly to the interpretation of human physiological evolution.

For the remainder of this article, the name Homo erectus will be used to describe a distinct species for the convenience of continuity.

Use of tools

Homo ergaster used more diverse and sophisticated stone tools than its predecessors. H. erectus, however, used comparatively primitive tools. This is possibly because H. ergaster first used tools of Oldowan technology and later progressed to the Acheulean[45] while the use of Acheulean tools began ca. 1.8 million years ago,[46] the line of H. erectus diverged some 200,000 years before the general innovation of Acheulean technology. Thus the Asian migratory descendants of H. ergaster made no use of any Acheulean technology. In addition, it has been suggested that H. erectus may have been the first hominid to use rafts to travel over oceans.[47] The oldest recorded stone tool ever to be found in Turkey reveals that humans passed through the gateway from Asia to Europe much earlier than previously thought, approximately 1.2 million years ago.[48]

Use of fire

East African sites, such as Chesowanja near Lake Baringo, Koobi Fora, and Olorgesailie in Kenya, show some possible evidence that fire was utilized by early humans. At Chesowanja, archaeologists found red clay sherds dated to be 1.42 Mya.[49] Reheating on these shards show that the clay must have been heated to 400 °C (752 °F) to harden. At Koobi Fora, two sites show evidence of control of fire by Homo erectus at 1.5 Mya, with reddening of sediment that can only come from heating at 200–400 °C (392–752 °F).[49] A "hearth-like depression" exists at a site in Olorgesailie, Kenya. Some microscopic charcoal was found, but it could have resulted from a natural brush fire.[49] In Gadeb, Ethiopia, fragments of welded tuff that appeared to have been burned were found in Locality 8E, but re-firing of the rocks may have occurred due to local volcanic activity.[49] These have been found alongside H. erectus–created Acheulean artifacts. In the Middle Awash River Valley, cone-shaped depressions of reddish clay were found that could have been created by temperatures of 200 °C (392 °F). These features are thought to be burned tree stumps such that they would have fire away from their habitation site.[49] Burnt stones are also found in the Awash Valley, but volcanic welded tuff is also found in the area.

A site at Bnot Ya'akov Bridge, Israel has been claimed to show that H. erectus or H. ergaster obtained control of fire between 790,000 and 690,000 BP.[50] To date this has been the most widely accepted claim, although recent reanalysis of burnt bone fragments and plant ashes from the Wonderwerk Cave have sparked claims of evidence supporting human control of fire by 1 Ma.[51]

Cooking

There is no archaeological evidence that Homo erectus cooked their food. The idea has been suggested,[52] but is not generally accepted.[53][54] It is known, from the study of microwear on handaxes, that meat formed a major part of the erectus diet. Meat is digestible without cooking, and is sometimes eaten raw by modern humans. Nuts, berries, fruits are also edible without cooking. Thus cooking cannot be presumed: the issue rests on clear evidence from archaeological sites, which at present does not exist.

Sociality

Homo erectus was probably the first hominid to live in a hunter-gatherer society, and anthropologists such as Richard Leakey believe that it was socially more like modern humans than the more Australopithecus-like species before it. Likewise, increased cranial capacity generally coincides with the more sophisticated tools occasionally found with fossils.

The discovery of Turkana boy (H. ergaster) in 1984 gave evidence that, despite its Homo-sapiens-like anatomy, it may not have been capable of producing sounds comparable to modern human speech. Ergaster likely communicated in a proto-language lacking the fully developed structure of modern human language but more developed than the non-verbal communication used by chimpanzees.[55] Such inference has been challenged by the discovery of H. ergaster/erectus vertebrae some 150,000 years older than the Turkana Boy in Dmanisi, Georgia, that reflect vocal capabilities within the range of H. sapiens.[56] Both brain size and the presence of the Broca's area also support the use of articulate language.[57]

H. erectus was probably the first hominid to live in small, familiar band-societies similar to modern hunter-gatherer band-societies.[58] H. erectus/ergaster is thought to be the first hominid to hunt in coordinated groups, use complex tools, and care for infirm or weak companions.

There has been some debate as to whether H. erectus, and possibly the later Neanderthals,[59] may have interbred with anatomically modern humans in Europe and Asia. See Neanderthal admixture theory.[60]

Descendants and subspecies

Homo erectus remains one of the most long-lived species of Homo, having existed over a million years, while Homo sapiens so far has existed for 200,000 years. If considering Homo erectus in its strict sense as only referring to the Asian variety, no consensus has been reached as to whether it is ancestral to H. sapiens or any later hominids.

- Homo erectus

- Homo erectus erectus (Java Man)

- Homo erectus yuanmouensis (Yuanmou Man)

- Homo erectus lantianensis (Lantian Man)

- Homo erectus nankinensis (Nanjing Man)

- Homo erectus pekinensis (Peking Man)

- Homo erectus palaeojavanicus (Meganthropus)

- Homo erectus soloensis (Solo Man)

- Homo erectus tautavelensis (Tautavel Man)

- Homo erectus georgicus

Related species

- Homo ergaster

- Homo floresiensis

- Homo antecessor

- Homo heidelbergensis

- Homo sapiens

- Homo sapiens idaltu

- Homo sapiens sapiens

- Homo neanderthalensis

- Homo rhodesiensis

- Homo cepranensis

Previously referred taxa

- Homo erectus wushanensis (actually a stem-orangutan)

The discovery of Homo floresiensis in 2003 and of the recentness of its extinction has raised the possibility that numerous descendant species of Homo erectus may have existed in the islands of Southeast Asia and await fossil discovery (see Orang Pendek). Homo erectus soloensis, who was long assumed to have lived on Java at least as late as about 50,000 years ago but was re-dated in 2011 to a much higher age,[61] would be one of them. Some scientists are skeptical of the claim that Homo floresiensis is a descendant of Homo erectus. One explanation holds that the fossils are of a modern human with microcephaly, while another one holds that they are from a group of pygmies.

Individual fossils

Some of the major Homo erectus fossils:

- Indonesia (island of Java): Trinil 2 (holotype), Sangiran collection, Sambungmachan collection,[62] Ngandong collection

- China ("Peking Man"): Lantian (Gongwangling and Chenjiawo), Yunxian, Zhoukoudian, Nanjing, Hexian

- Kenya: KNM ER 3883, KNM ER 3733

- Vértesszőlős, Hungary "Samu"

- Vietnam: Northern, Tham Khuyen,[63] Hoa Binh

- Republic of Georgia: Dmanisi collection ("Homo erectus georgicus")

- Ethiopia: Daka calvaria

- Eritrea: Buia cranium (possibly H. ergaster)[64]

- Denizli Province, Turkey: Kocabas fossil[65]

Gallery

|

See also

General:

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hazarika, Manji (16–30 June 2007). "Homo erectus/ergaster and Out of Africa: Recent Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology" (PDF).

- ↑ Chauhan, Parth R. (2003) "Distribution of Acheulian sites in the Siwalik region" in An Overview of the Siwalik Acheulian & Reconsidering Its Chronological Relationship with the Soanian – A Theoretical Perspective. assemblage.group.shef.ac.uk

- ↑ See overview of theories on human evolution.

- ↑ Klein, R. (1999). The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226439631.

- ↑ Antón, S. C. (2003). "Natural history of Homo erectus". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 122: 126–170. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10399.

By the 1980s, the growing numbers of H. erectus specimens, particularly in Africa, led to the realization that Asian H. erectus (H. erectus sensu stricto), once thought so primitive, was in fact more derived than its African counterparts. These morphological differences were interpreted by some as evidence that more than one species might be included in H. erectus sensu lato (e.g., Stringer, 1984; Andrews, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1984, 1991a, b; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000) ... Unlike the European lineage, in my opinion, the taxonomic issues surrounding Asian vs. African H. erectus are more intractable. The issue was most pointedly addressed with the naming of H. ergaster on the basis of the type mandible KNM-ER 992, but also including the partial skeleton and isolated teeth of KNM-ER 803 among other Koobi Fora remains (Groves and Mazak, 1975). Recently, this specific name was applied to most early African and Georgian H. erectus in recognition of the less-derived nature of these remains vis à vis conditions in Asian H. erectus (see Wood, 1991a, p. 268; Gabunia et al., 2000a). It should be noted, however, that at least portions of the paratype of H. ergaster (e.g., KNM-ER 1805) are not included in most current conceptions of that taxon. The H. ergaster question remains famously unresolved (e.g., Stringer, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1991a, 1994; Rightmire, 1998b; Gabunia et al., 2000a; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000), in no small part because the original diagnosis provided no comparison with the Asian fossil record

- ↑ Suwa G; Asfaw B; Haile-Selassie Y; White T; Katoh S; WoldeGabriel G; Hart W; Nakaya H; Beyene Y (2007). "Early Pleistocene Homo erectus fossils from Konso, southern Ethiopia". Anthropological Science 115 (2): 133. doi:10.1537/ase.061203.

- ↑ Skull suggests three early human species were one : Nature News & Comment

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 David Lordkipanidze, Marcia S. Ponce de Leòn, Ann Margvelashvili, Yoel Rak, G. Philip Rightmire, Abesalom Vekua, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer (18 October 2013). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo". Science 342 (6156): 326–331. doi:10.1126/science.1238484.

- ↑ Switek, Brian (17 October 2013). "Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ Frazier, Kendrick (Nov–Dec 2006). "Leakey Fights Church Campaign to Downgrade Kenya Museum’s Human Fossils". Skeptical Inquirer magazine 30 (6). Archived from the original on 2009-01-10.

- ↑ Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana and McBride, Bunny (2007). Evolution and prehistory: the human challenge. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7.

- ↑ Ferring, R.; Oms, O.; Agusti, J.; Berna, F.; Nioradze, M.; Shelia, T.; Tappen, M.; Vekua, A.; Zhvania, D.; Lordkipanidze, D. (2011). "Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (26): 10432. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108.

- ↑ New discovery suggests Homo erectus originated from Asia. Dnaindia.com. 8 June 2011.

- ↑ pithecos

- ↑ anthropos

- ↑ from sino-, a combining form of the Greek Σίνα, "China", and the Latinate pekinensis, "of Peking"

- ↑ Darwin, Charles R. (1871). The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray. ISBN 0-8014-2085-7.

- ↑ Spoor F, Leakey MG, Gathogo PN et al. (August 2007). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature 448 (7154): 688–91. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323.

- ↑ ROBINSON JT (January 1953). "The nature of Telanthropus capensis". Nature 171 (4340): 33. doi:10.1038/171033a0. PMID 13025468.

- ↑ Frederick E. Grine; John G. Fleagle; Richard E. Leakey (1 Jun 2009). "Chapter 2: Homo habilis—A Premature Discovery: Remember by One of Its Founding Fathers, 42 Years Later". The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo. Springer. p. 7.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kalb, Jon E (2001). Adventures in the Bone Trade: The Race to Discover Human Ancestors in Ethiopia's Afar Depression. Springer. p. 76. ISBN 0-387-98742-8. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Wood, Bernard (11 July 2002). "Palaeoanthropology: Hominid revelations from Chad" (PDF). Nature 418 (6894): 133–135. doi:10.1038/418133a. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Cornevin, Robert (1967). Histoire de l'Afrique. Payotte. p. 440. ISBN 2-228-11470-7.

- ↑ "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive". Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Vekua A, Lordkipanidze D, Rightmire GP, Agusti J, Ferring R, Maisuradze G, Mouskhelishvili A, Nioradze M, De Leon MP, Tappen M, Tvalchrelidze M, Zollikofer C (2002). "A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia". Science 297 (5578): 85–9. doi:10.1126/science.1072953. PMID 12098694.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Lordkipanidze D, Jashashvili T, Vekua A, Ponce de León MS, Zollikofer CP, Rightmire GP, Pontzer H, Ferring R, Oms O, Tappen M, Bukhsianidze M, Agusti J, Kahlke R, Kiladze G, Martinez-Navarro B, Mouskhelishvili A, Nioradze M, Rook L (2007). "Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia" (PDF). Nature 449 (7160): 305–310. doi:10.1038/nature06134. PMID 17882214.

- ↑ Lordkipanidze, D.; Vekua, A.; Ferring, R.; Rightmire, G. P.; Agusti, J.; Kiladze, G.; Mouskhelishvili, A.; Nioradze, M.; Ponce De León, M. S. P.; Tappen, M.; Zollikofer, C. P. E. (2005). "Anthropology: The earliest toothless hominin skull". Nature 434 (7034): 717–718. doi:10.1038/434717b. PMID 15815618.

- ↑ Augusti, Jordi; Lordkipanidze, David (June 2011). "How "African" was the early human dispersal out of Africa?". Quaternary Science Reviews 30 (11–12): 1338–1342. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012.

- ↑ Gibbons, A. (2003). "A Shrunken Head for African Homo erectus" (PDF). Science 300 (5621): 893a. doi:10.1126/science.300.5621.893a.

- ↑ Tattersall, I.; Schwartz, J. H. (2009). "Evolution of the GenusHomo". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 37: 67. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100202.

- ↑ Rightmire, G. P.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Vekua, A. (2006). "Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia". Journal of Human Evolution 50 (2): 115–141. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.07.009. PMID 16271745.

- ↑ Gabunia, L.; Vekua, A.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Swisher Cc, 3.; Ferring, R.; Justus, A.; Nioradze, M.; Tvalchrelidze, M.; Antón, S. C.; Bosinski, G.; Jöris, O.; Lumley, M. A.; Majsuradze, G.; Mouskhelishvili, A. (2000). "Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age". Science 288 (5468): 1019–1025. doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.1019. PMID 10807567.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (19 September 2007). "New Fossils Offer Glimpse of Human Ancestors". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ↑ Rightmire, G. Philip; Van Arsdale, Adam P.; Lordkipanidze, David (2008). "Variation in the mandibles from Dmanisi, Georgia". Journal of Human Evolution 54 (6): 904–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.02.003. PMID 18394678.

- ↑ Ian Sample (17 October 2013). "Skull of Homo erectus throws story of human evolution into disarray". The Guardian.

- ↑ Weidenreich, F. (1943). "The "Neanderthal Man" and the ancestors of "Homo Sapiens"". American Anthropologist 45: 39–48. doi:10.1525/aa.1943.45.1.02a00040. JSTOR 662864.

- ↑ Jelinek, J. (1978). "Homo erectus or Homo sapiens?". Rec. Adv. Primatol. 3: 419–429.

- ↑ Wolpoff, M.H. (1984). "Evolution of Homo erectus: The question of stasis". Palaeobiology 10 (4): 389–406. JSTOR 2400612.

- ↑ Frayer, D.W., Wolpoff, M.H.; Thorne, A.G.; Smith, F.H. and Pope, G.G. (1993). "Theories of modern human origins: The paleontological test". American Anthropologist 95: 14–50. doi:10.1525/aa.1993.95.1.02a00020. JSTOR 681178.

- ↑ Tattersall, Ian and Jeffrey Schwartz (2001). Extinct Humans. Boulder, Colorado: Westview/Perseus. ISBN 0-8133-3482-9.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Swisher, Carl Celso III; Curtis, Garniss H. and Lewin, Roger (2002) Java Man, Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11473-0.

- ↑ Bryson, Bill (2005). A Short History of Nearly Everything: Special Illustrated Edition. Toronto: Doubleday Canada. ISBN 0-385-66198-3.

- ↑ Khanna, Dev Raj (2004). Human Evolution. Discovery Publishing House. p. 195. ISBN 978-8171417759. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

African H. erectus, with a mean stature of 170 cm, would be in the tallest 17 percent of modern populations, even if we make comparisons only with males

- ↑ Roylance, Frank D. Roylance (6 February 1994). "A Kid Tall For His Age". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

Clearly this population of early people were tall, and fit. Their long bones were very strong. We believe their activity level was much higher than we can imagine today. We can hardly find Olympic athletes with the stature of these people

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C. and Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑ The Earth Institute. (2011-09-01). Humans Shaped Stone Axes 1.8 Million Years Ago, Study Says. Columbia University. Accessed 5 January 2012.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (13 March 1998). "Paleoanthropology: Ancient Island Tools Suggest Homo erectus Was a Seafarer". Science 279 (5357): 1635–1637. doi:10.1126/science.279.5357.1635.

- ↑ Oldest stone tool ever found in Turkey discovered by the University of Royal Holloway London and published in ScienceDaily on December 23, 2014

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 James, Steven R. (February 1989). "Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence" (PDF). Current Anthropology (University of Chicago Press) 30 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1086/203705. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (29 April 2004). "Early human fire skills revealed". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ↑ Pringle, Heather (2 April 2012), "Quest for Fire Began Earlier Than Thought", ScienceNOW (American Association for the Advancement of Science), retrieved 2012-04-04

- ↑ Wrangham, Richard (2009). Catching Fire. Basic Books.

- ↑ Adrienne Zihlman; Nancy Tanner (1972). "Gathering and the Hominid Adaptation". In Lionel Tiger, Heather T. Fowler. Female Hierarchies. Beresford Book Service. pp. 220–229.

- ↑ Fedigan, Linda Marie (1986). "The Changing Role of Women in Models of Human Evolution". Annual Review of Anthropology 15: 25–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.15.100186.000325.

- ↑ Ruhlen, Merritt (1994). The origin of language: tracing the evolution of the mother tongue. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-58426-6.

- ↑ Bower, Bruce (3 May 2006). "Evolutionary back story: Thoroughly modern spine supported human ancestor". Science News 169 (18): 275–276. doi:10.2307/4019325.

- ↑ Richard Leakey (1992). Origins Reconsidered. Anchor. pp. 257–258. ISBN 0-385-41264-9.

- ↑ Boehm, Christopher (1999). Hierarchy in the forest: the evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-674-39031-8.

- ↑ Owen, James (30 October 2006). "Neanderthals, Modern Humans Interbred, Bone Study Suggests". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Whitfield, John (18 February 2008). "Lovers not fighters". Scientific American.

- ↑ Finding showing human ancestor older than previously thought offers new insights into evolution, 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Delson E, Harvati K, Reddy D et al. (April 2001). "The Sambungmacan 3 Homo erectus calvaria: a comparative morphometric and morphological analysis". The Anatomical Record 262 (4): 380–97. doi:10.1002/ar.1048. PMID 11275970.

- ↑ Ciochon R, Long VT, Larick R et al. (April 1996). "Dated co-occurrence of Homo erectus and Gigantopithecus from Tham Khuyen Cave, Vietnam". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (7): 3016–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.7.3016. PMC 39753. PMID 8610161.

- ↑ http://archive.archaeology.org/9809/newsbriefs/eritrea.html[]

- ↑ Kappelman J, Alçiçek MC, Kazanci N, Schultz M, Ozkul M, Sen S (January 2008). "First Homo erectus from Turkey and implications for migrations into temperate Eurasia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 135 (1): 110–6. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20739. PMID 18067194.

External links

- Homo erectus Origins - Exploring the Fossil Record - Bradshaw Foundation

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo erectus. |

- Archaeology Info

- Homo erectus – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Possible co-existence with Homo Habilis – BBC News

- John Hawks's discussion of the Kocabas fossil

- Peter Brown's Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)