Homeschooling

Homeschooling, also known as home education, is the education of children inside the home, as opposed to in the formal settings of a public or private school. Home education is usually conducted by a parent or tutor. Many families that start out with a formal school structure at home often switch to less formal and, in their view, more effective ways of imparting education outside of school, and many prefer the term "home education" to the more prevalently used "homeschooling".[1] "Homeschooling" is the term commonly used in North America, whereas "home education" is more commonly used in the United Kingdom,[2] elsewhere in Europe, and in many Commonwealth countries.

Prior to the introduction of compulsory school attendance laws, most childhood education was imparted by the family or community.[3] However, in developed countries, homeschooling in the modern sense is an alternative to attending public or private schools, and is a legal option for parents in many countries.

Parents cite two main motivations for homeschooling their children: dissatisfaction with the local schools and the interest in increased involvement with (and greater control over) their children's learning and development. Parents' dissatisfaction with available schools includes concerns about the school environment, the quality of academic instruction, the curriculum, and bullying as well as lack of faith in the school's ability to cater to their child's special needs. Some parents homeschool in order to have greater control over what and how their children are taught, to better cater for children's individual aptitudes and abilities adequately, to provide a specific religious or moral instruction, and to take advantage of the efficiency of one-to-one instruction, which allows the child to spend more time on childhood activities, socializing, and non-academic learning. Many parents are also influenced by alternative educational philosophies espoused by the likes of Susan Sutherland Isaacs, Charlotte Mason, John Holt, and Sir Kenneth Robinson, among others.

Homeschooling may also be a factor in the choice of parenting style. Homeschooling can be an option for families living in isolated rural locations, for those temporarily abroad, and for those who travel frequently. Many young athletes, actors, and musicians are taught at home to better accommodate their training and practice schedules. Homeschooling can be about mentorship and apprenticeship, in which a tutor or teacher is with the child for many years and gets to know the child very well. Recently, homeschooling has increased in popularity in the United States, and the percentage of children ages 5 through 17 who are homeschooled increased from 1.7% in 1999 to 2.9% in 2007.[4]

Homeschooling can be used as a form of supplemental education and as a way of helping children learn under specific circumstances. The term may also refer to instruction in the home under the supervision of correspondence schools or umbrella schools. In some places, an approved curriculum is legally required if children are homeschooled.[5] A curriculum-free philosophy of homeschooling is sometimes called unschooling, a term coined in 1977 by American educator and author John Holt in his magazine Growing Without Schooling. In some cases, a liberal arts education is provided using the trivium and quadrivium as the main models.

History

For much of history and in many cultures, enlisting professional teachers (whether as tutors or in a formal academic setting) was an option available only to the elite social classes. Thus, until relatively recently, the vast majority of people, especially during early childhood, were educated by family members, family friends, or anyone with useful knowledge.[3]

The earliest public schools in modern Western culture were established in the early 16th century in the German states of Gotha and Thuringia.[6] However, even in the 18th century, the majority of people in Europe lacked formal schooling, meaning they were homeschooled, tutored, or received no education at all.[7] Regional differences in schooling existed in colonial America; in the south, farms and plantations were so widely dispersed that community schools such as those in the more compact settlements were impossible. In the middle colonies, the educational situation varied when comparing New York with New England [8] until the 1850s.[9] Formal schooling in a classroom setting has been the most common means of schooling throughout the world, especially in developed countries, since the early- and mid-19th century. Native Americans, who traditionally used homeschooling and apprenticeship, vigorously resisted compulsory education in the United States.[10]

In the 1960s, Rousas John Rushdoony began to advocate homeschooling, which he saw as a way to combat the intentionally secular nature of the public school system in the United States.[11] He vigorously attacked progressive school reformers such as Horace Mann and John Dewey, and argued for the dismantling of the state's influence in education in three works: Intellectual Schizophrenia, a general and concise study of education, The Messianic Character of American Education, a history and castigation of public education in the U.S., and The Philosophy of the Christian Curriculum, a parent-oriented pedagogical statement. Rushdoony was frequently called as an expert witness by the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA) in court cases.

During this time, American educational professionals Raymond and Dorothy Moore began to research the academic validity of the rapidly growing Early Childhood Education movement. This research included independent studies by other researchers and a review of over 8,000 studies bearing on early childhood education and the physical and mental development of children.

They asserted that formal schooling before ages 8–12 not only lacked the anticipated effectiveness, but also harmed children. The Moores published their view that formal schooling was damaging young children academically, socially, mentally, and even physiologically. The Moores presented evidence that childhood problems such as juvenile delinquency, nearsightedness, increased enrollment of students in special education classes and behavioral problems were the result of increasingly earlier enrollment of students.[12] The Moores cited studies demonstrating that orphans who were given surrogate mothers were measurably more intelligent, with superior long-term effects – even though the mothers were "mentally retarded teenagers" – and that illiterate tribal mothers in Africa produced children who were socially and emotionally more advanced than typical western children, "by western standards of measurement".[12]

Their primary assertion was that the bonds and emotional development made at home with parents during these years produced critical long-term results that were cut short by enrollment in schools, and could neither be replaced nor corrected in an institutional setting afterward.[12] Recognizing a necessity for early out-of-home care for some children, particularly special needs and impoverished children and children from exceptionally inferior homes, they maintained that the vast majority of children were far better situated at home, even with mediocre parents, than with the most gifted and motivated teachers in a school setting. They described the difference as follows: "This is like saying, if you can help a child by taking him off the cold street and housing him in a warm tent, then warm tents should be provided for all children – when obviously most children already have even more secure housing."[12]

Like Holt, the Moores embraced homeschooling after the publication of their first work, Better Late Than Early, in 1975, and went on to become important homeschool advocates and consultants with the publication of books such as Home Grown Kids, 1981, Homeschool Burnout and others.

Simultaneously, other authors published books questioning the premises and efficacy of compulsory schooling, including Deschooling Society by Ivan Illich, 1970 and No More Public School by Harold Bennet, 1972.

In 1976, Holt published Instead of Education; Ways to Help People Do Things Better. In its conclusion, he called for a "Children's Underground Railroad" to help children escape compulsory schooling.[13] In response, Holt was contacted by families from around the U.S. to tell him that they were educating their children at home. In 1977, after corresponding with a number of these families, Holt began producing Growing Without Schooling, a newsletter dedicated to home education.[14]

In 1980, Holt said, "I want to make it clear that I don't see homeschooling as some kind of answer to badness of schools. I think that the home is the proper base for the exploration of the world which we call learning or education. Home would be the best base no matter how good the schools were."[15]

Holt later wrote a book about homeschooling, Teach Your Own, in 1981.

One common theme in the homeschool philosophies of both Holt and that of the Moores is that home education should not attempt to bring the school construct into the home, or be seen as a view of education as an academic preliminary to life. They viewed home education as a natural, experiential aspect of life that occurs as the members of the family are involved with one another in daily living.

Methodology

Homeschools use a wide variety of methods and materials. Families, for a variety of reasons (parent education, finances, educational philosophies, future educational plans, where they live, past educational experiences of the child, child’s interests and temperament) choose different educational methods, which represent a variety of educational philosophies and paradigms. Some of the methods used include Classical education (including Trivium, Quadrivium), Charlotte Mason education, Montessori method, Theory of multiple intelligences, Unschooling, Radical Unschooling, Waldorf education, School-at-home (curriculum choices from both secular and religious publishers), A Thomas Jefferson Education, unit studies, curriculum made up from private or small publishers, apprenticeship, hands-on-learning, distance learning (both on-line and correspondence), dual enrollment in local schools or colleges, and curriculum provided by local schools and many others. Some of these approaches are used in private and public schools. Educational research and studies support the use of some of these methods. Unschooling, natural learning, Charlotte Mason Education, Montessori, Waldorf, apprenticeship, hands-on-learning, unit studies are supported to varying degrees by research by constructivist learning theories and situated cognitive theories. Elements of these theories may be found in the other methods as well. A student’s education may be customized to support his or her learning level, style, and interests.[16] It is not uncommon for a student to experience more than one approach as the family discovers what works best as the students grow and their circumstances change. Many families use an eclectic approach, picking and choosing from various suppliers. For sources of curricula and books, "Homeschooling in the United States: 2003"[17] found that 78 percent utilized "a public library"; 77 percent used "a homeschooling catalog, publisher, or individual specialist"; 68 percent used "retail bookstore or other store"; 60 percent used "an education publisher that was not affiliated with homeschooling." "Approximately half" used curriculum or books from "a homeschooling organization", 37 percent from a "church, synagogue or other religious institution" and 23 percent from "their local public school or district." 41 percent in 2003 utilized some sort of distance learning, approximately 20 percent by "television, video or radio"; 19 percent via "Internet, e-mail, or the World Wide Web"; and 15 percent taking a "correspondence course by mail designed specifically for homeschoolers." Individual governmental units, e. g. states and local districts, vary in official curriculum and attendance requirements.[18]

Unit studies

In a unit study approach, multiple subjects such as math, science, history, art, and geography, are studied in relation to a single topic such as Native Americans, ancient Rome, or whales. For example, a unit study of Native Americans might combine age-appropriate lessons and projects teaching literature (Native American legends), writing (report on a famous native American), vocabulary and spelling (Native American words that are now part of the English language), art and crafts (pottery, beadwork, sand painting, making moccasins), geography (original locations of tribes in the Americas), social studies (cultures of the different tribes), and science (plants and animals used by Native Americans). Unit studies may be purchased or be parent prepared.[19] Unit studies are useful for teaching multiple grades simultaneously as the difficulty level can be adjusted for each student.[20] An extended form of unit studies, Integrated Thematic Instruction utilizes one central theme integrated throughout the curriculum so that students finish a school year with a deep understanding of a certain broad subject or idea.

All-in-one curricula

All-in-one homeschooling curricula (variously known as "school-at-home", "The Traditional Approach", "school-in-a-box" or "The Structured Approach"), are instructionist methods of teaching in which the curriculum and homework of the student are similar or identical to those used in a public or private school. Purchased as a grade level package or separately by subject, the package may contain all of the needed books, materials, internet access for remote testing, traditional tests, answer keys, and extensive teacher guides. These materials cover the same subject areas as do public schools, allowing for an easy transition back into the school system. These are among the more expensive options for homeschooling, but they require minimal preparation and are easy to use. Examples of curriculum providers are K12.com,[21] Calvert School, A Beka Book, Bob Jones Press, Alpha Omega Publications, Educator’s Publishing Service, My Father's World, Sonlight, Modern Curriculum Press, University of North Dakota Distance Education,[22] etc. Some localities provide the same materials used at local schools to homeschoolers. The purchase of a complete curriculum and their teaching/grading service from an accredited distance learning curriculum provider may allow students to obtain an accredited high school diploma.[23][24]

Unschooling and natural learning

Some people use the terms "unschooling" or "radical unschooling" to describe all methods of education that are not based in a school.

"Natural learning" refers to a type of learning-on-demand where children pursue knowledge based on their interests and parents take an active part in facilitating activities and experiences conducive to learning but do not rely heavily on textbooks or spend much time "teaching", looking instead for "learning moments" throughout their daily activities. Parents see their role as that of affirming through positive feedback and modeling the necessary skills, and the child's role as being responsible for asking and learning.

The term "unschooling" as coined by John Holt describes an approach in which parents do not authoritatively direct the child's education, but interact with the child following the child's own interests, leaving them free to explore and learn as their interests lead.[15][17] "Unschooling" does not indicate that the child is not being educated, but that the child is not being "schooled", or educated in a rigid school-type manner. Holt asserted that children learn through the experiences of life, and he encouraged parents to live their lives with their child. Also known as interest-led or child-led learning, unschooling attempts to follow opportunities as they arise in real life, through which a child will learn without coercion. An unschooled child may utilize texts or classroom instruction, but these are not considered central to education. Holt asserted that there is no specific body of knowledge that is, or should be, required of a child.[18]

"Unschooling" should not be confused with "deschooling," which may be used to indicate an anti-"institutional school" philosophy, or a period or form of deprogramming for children or parents who have previously been schooled.

Both unschooling and natural learning advocates believe that children learn best by doing; a child may learn reading to further an interest about history or other cultures, or math skills by operating a small business or sharing in family finances. They may learn animal husbandry keeping dairy goats or meat rabbits, botany tending a kitchen garden, chemistry to understand the operation of firearms or the internal combustion engine, or politics and local history by following a zoning or historical-status dispute. While any type of homeschoolers may also use these methods, the unschooled child initiates these learning activities. The natural learner participates with parents and others in learning together.

Another prominent proponent of unschooling is John Taylor Gatto, author of Dumbing Us Down, The Exhausted School, A Different Kind of Teacher, and Weapons of Mass Instruction. Gatto argues that public education is the primary tool of "state controlled consciousness" and serves as a prime illustration of the total institution — a social system which impels obedience to the state and quells free thinking or dissent.[25]

Autonomous learning

Autonomous learning is a school of education which sees learners as individuals who can and should be autonomous i.e. be responsible for their own learning climate.

Autonomous education helps students develop their self-consciousness, vision, practicality and freedom of discussion. These attributes serve to aid the student in his/her independent learning.

Autonomous learning is very popular with those who home educate their children. The child usually gets to decide what projects they wish to tackle or what interests to pursue. In home education this can be instead of or in addition to regular subjects like doing math or English.

According to Home Education UK the autonomous education philosophy emerged from the epistemology of Karl Popper in The Myth of the Framework: In Defence of Science and Rationality, which is developed in the debates, which seek to rebut the neo-Marxist social philosophy of convergence proposed by the Frankfurt School (e.g. Theodor W. Adorno, Jürgen Habermas, Max Horkheimer).

Homeschool cooperatives

A Homeschool Cooperative is a cooperative of families who homeschool their children. It provides an opportunity for children to learn from other parents who are more specialized in certain areas or subjects. Co-ops also provide social interaction for homeschooled children. They may take lessons together or go on field trips. Some co-ops also offer events such as prom and graduation for homeschoolers.

Homeschoolers are beginning to utilize Web 2.0 as a way to simulate homeschool cooperatives online. With social networks homeschoolers can chat, discuss threads in forums, share information and tips, and even participate in online classes via blackboard systems similar to those used by colleges.

Research

Supportive

Test results

According to the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA) in 2004, "Many studies over the last few years have established the academic excellence of homeschooled children."[26] Homeschooling Achievement—a compilation of studies published by the HSLDA—supported the academic integrity of homeschooling. This booklet summarized a 1997 study by Ray and the 1999 Rudner study.[27] The Rudner study noted two limitations of its own research: it is not necessarily representative of all homeschoolers and it is not a comparison with other schooling methods.[28] Among the homeschooled students who took the tests, the average homeschooled student outperformed his public school peers by 30 to 37 percentile points across all subjects. The study also indicates that public school performance gaps between minorities and genders were virtually non-existent among the homeschooled students who took the tests.[29]

A study conducted in 2008 found that 11,739 homeschooled students, on average, scored 37 percentile points above public school students on standardized achievement tests.[30] This is consistent with the Rudner study (1999). However, Rudner has said that these same students in public school may have scored just as well because of the dedicated parents they had.[31] The Ray study also found that homeschooled students who had a certified teacher as a parent scored one percentile lower than homeschooled students who did not have a certified teacher as a parent.[30]

In 2011, Martin-Chang found that unschooling children ages 5–10 scored significantly below traditionally educated children, while academically oriented homeschooled children scored from one half grade level above to 4.5 grade levels above traditionally schooled children on standardized tests (n=37 home schooled children matched with children from the same socioeconomic and educational background).[32]

In the 1970s, Raymond S. and Dorothy N. Moore conducted four federally funded analyses of more than 8,000 early childhood studies, from which they published their original findings in Better Late Than Early, 1975. This was followed by School Can Wait, a repackaging of these same findings designed specifically for educational professionals.[33] They concluded that, "where possible, children should be withheld from formal schooling until at least ages eight to ten." Their reason was that children "are not mature enough for formal school programs until their senses, coordination, neurological development and cognition are ready". They concluded that the outcome of forcing children into formal schooling is a sequence of "1) uncertainty as the child leaves the family nest early for a less secure environment, 2) puzzlement at the new pressures and restrictions of the classroom, 3) frustration because unready learning tools – senses, cognition, brain hemispheres, coordination – cannot handle the regimentation of formal lessons and the pressures they bring, 4) hyperactivity growing out of nerves and jitter, from frustration, 5) failure which quite naturally flows from the four experiences above, and 6) delinquency which is failure's twin and apparently for the same reason."[34] According to the Moores, "early formal schooling is burning out our children. Teachers who attempt to cope with these youngsters also are burning out."[34] Aside from academic performance, they think early formal schooling also destroys "positive sociability", encourages peer dependence, and discourages self-worth, optimism, respect for parents, and trust in peers. They believe this situation is particularly acute for boys because of their delay in maturity. The Moores cited a Smithsonian Report on the development of genius, indicating a requirement for "1) much time spent with warm, responsive parents and other adults, 2) very little time spent with peers, and 3) a great deal of free exploration under parental guidance."[34] Their analysis suggested that children need "more of home and less of formal school", "more free exploration with... parents, and fewer limits of classroom and books", and "more old fashioned chores – children working with parents – and less attention to rivalry sports and amusements."[34]

Socialization

Using the Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale, John Taylor later found that, "while half of the conventionally schooled children scored at or below the 50th percentile (in self-concept), only 10.3% of the home-schooling children did so."[35] He further stated that "the self-concept of home-schooling children is significantly higher statistically than that of children attending conventional school. This has implications in the areas of academic achievement and socialization which have been found to parallel self-concept. Regarding socialization, Taylor's results would mean that very few home-schooling children are socially deprived. He states that critics who speak out against homeschooling on the basis of social deprivation are actually addressing an area which favors homeschoolers.[35]

In 2003, the National Home Education Research Institute conducted a survey of 7,300 U.S. adults who had been homeschooled (5,000 for more than seven years). Their findings included:

- Homeschool graduates are active and involved in their communities. 71% participate in an ongoing community service activity, like coaching a sports team, volunteering at a school, or working with a church or neighborhood association, compared with 37% of U.S. adults of similar ages from a traditional education background.

- Homeschool graduates are more involved in civic affairs and vote in much higher percentages than their peers. 76% of those surveyed between the ages of 18 and 24 voted within the last five years, compared with only 29% of the corresponding U.S. populace. The numbers are even greater in older age groups, with voting levels not falling below 95%, compared with a high of 53% for the corresponding U.S. populace.

- 58.9% report that they are "very happy" with life, compared with 27.6% for the general U.S. population. 73.2% find life "exciting", compared with 47.3%.[36]

Criticism

People claim the studies that show that homeschooled students do better on standardized tests[30][37] compare voluntary homeschool testing with mandatory public-school testing.

By contrast, SAT and ACT tests are self-selected by homeschooled and formally schooled students alike. Homeschoolers averaged higher scores on these college entrance tests in South Carolina.[38] Other scores (1999 data) showed mixed results, for example showing higher levels for homeschoolers in English (homeschooled 23.4 vs national average 20.5) and reading (homeschooled 24.4 vs national average 21.4) on the ACT, but mixed scores in math (homeschooled 20.4 vs national average 20.7 on the ACT as opposed homeschooled 535 vs national average 511 on the 1999 SAT math).[39]

Some advocates of homeschooling and educational choice counter with an input-output theory, pointing out that home educators expend only an average of $500–$600 a year on each student, in comparison to $9,000-$10,000 for each public school student in the United States, which suggests home-educated students would be especially dominant on tests if afforded access to an equal commitment of tax-funded educational resources.[40]

Controversy and criticism

Opposition to homeschooling comes from some organizations of teachers and school districts. The National Education Association, a United States teachers' union and professional association, opposes homeschooling.[41][42] Criticisms by such opponents include:

- Inadequate standards of academic quality and comprehensiveness

- Lack of socialization with peers of different ethnic and religious backgrounds

- The potential for development of religious or social extremism/individualism

- Potential for development of parallel societies that do not fit into standards of citizenship and community

Stanford University political scientist Professor Rob Reich[43] (not to be confused with former U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich) wrote in The Civic Perils of Homeschooling (2002) that homeschooling can potentially give students a one-sided point of view, as their parents may, even unwittingly, block or diminish all points of view but their own in teaching. He also argues that homeschooling, by reducing students' contact with peers, reduces their sense of civic engagement with their community.[44]

Gallup polls of American voters have shown a significant change in attitude in the last 20 years, from 73% opposed to home education in 1985 to 54% opposed in 2001.[45]

Many teachers and school districts oppose the idea of homeschooling. However, research has shown that homeschooled children often excel in many areas of academic endeavor. According to a study done on the homeschool movement,[46] homeschoolers often achieve academic success and admission into elite universities. There is also evidence that most are remarkably well socialized. According to the National Home Education Research Institute president, Brian Ray, socialization is not a problem for homeschooling children, many of whom are involved in community sports, volunteer activities, book groups, or homeschool co-ops.[47] In addition, research shows that—in terms of self-concept, self-esteem, and the ability to get along in groups—homeschoolers do just as well as their public school peers in the school system.

According to an annual Gallup poll, public opinion is mixed. Respondents who regard homeschooling as a "bad thing" dropped from 73 percent in 1985 to 57 percent in 1997.[48] In 1988, when asked whether parents should have a right to choose homeschooling, 53 percent thought that they should, as revealed by another poll.[49]

International status and statistics

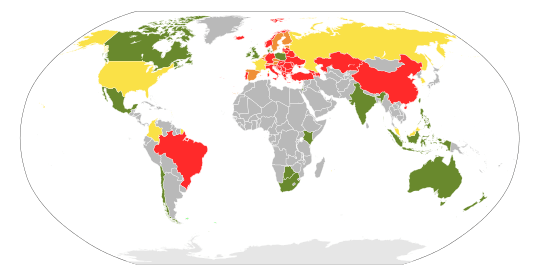

Homeschooling is legal in some countries. Countries with the most prevalent home education movements include Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Some countries have highly regulated home education programs as an extension of the compulsory school system; others, such as Sweden and Germany,[50][51] have outlawed it entirely. Brazil has a law project in process. In other countries, while not restricted by law, homeschooling is not socially acceptable or considered desirable and is virtually non-existent.

See also

- Homeschooling and alternative education in India

- Homeschooling in New Zealand

- Homeschooling in South Africa

- Homeschooling in the United States

- Home education in the United Kingdom

- List of homeschooled people

- Home School Legal Defense Association

- Informal learning

- List of homeschooling programmes

References

- ↑ "Informal learning, home education and homeschooling (home schooling)". YMCA George Williams College. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- ↑ "Official UK Government Page on Home Education". Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 A. Distefano, K. E. Rudestam, R. J. Silverman (2005) Encyclopedia of Distributed Learning (p221) ISBN 0-7619-2451-5

- ↑ "Number and percentage of homeschooled students ages 5 through 17 with a grade equivalent of kindergarten through 12th grade, by selected child, parent, and household characteristics: 1999, 2003, and 2007". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ↑ HSLDA. "Homeschooling in New York: A legal analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Education: Free and Compulsory – Mises Institute

- ↑ "Education" Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., vol. 8, p. 959.

- ↑ How they were schooled

- ↑ History of Alternative Education in the United States

- ↑ Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield: Liberty, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Law Review 377, 386 n.30

- ↑ Edgar, William (2007-01). "The Passing of R. J. Rushdoony". First Things. Retrieved 2014-04-23. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Better Late Than Early, Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy N. Moore, 1975

- ↑ Christine Field. The Old Schoolhouse Meets Up with Patrick Farenga About the Legacy of John Holt

- ↑

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 A Conversation with John Holt (1980)

- ↑ "12 Most Compelling Reasons to Homeschool Your Children". 12most.com. 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Homeschooling in the United States: 2003 – Executive Summary

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 HSLDA | Homeschooling-State

- ↑ Unit Study Approach. TheHomeSchoolMom.com.

- ↑ "Unit Studies by Amanda Bennett". Unitstudy.com. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ↑ K12.com

- ↑ "North Dakota Center for Distance Education". Ndcde.org. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ↑ How To Prepare For Homeschooling. Accessed 2008-03-24.

- ↑ School-at-home approach. Accessed 2008-03-24.

- ↑ John Taylor Gatto, Weapons of Mass Instruction (Odysseus Group, 2008).

- ↑ HSLDA | Academic Statistics on Homeschooling

- ↑ "Academic Achievement". HSLDA. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Achievement and Demographics of Home School Students". Education Policy Analysis Archives. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ HSLDA | Homeschooling Achievement

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Ray, Brian. "Progress Report 2009: Homeschool Academic Achievement and Demographics". Survey. National Home Education Research Institute. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ Welner, Kariane Mari; Kevin G. Welner (11 April 1999). "Contextualizing Homeschooling Data: A Response to Rudner". Education Policy Analysis Archives: Education Policy Analysis Archives - Arizona State University 7 (13). Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Martin-Chang, Sandra; Gould, O.N.; Meuse, R.E. (2011). "The impact of schooling on academic achievement: Evidence from home-schooled and traditionally-schooled students". Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science /Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement 43: 195–202. doi:10.1037/a0022697. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Better Late Than Early, Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy N. Moore, Seventh Printing, 1993, addendum

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy Moore. When Education Becomes Abuse: A Different Look at the Mental Health of Children

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Self-Concept in home-schooling children, John Wesley Taylor V, Ph.D., Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI

- ↑ HSLDA | Homeschooling Grows Up

- ↑ HSLDA | Academic Statistics on Homeschooling

- ↑ Homeschool Legal Defense Association. "Academic Statistics on Homeschooling." http://www.hslda.org/docs/nche/000010/200410250.asp

- ↑ Daniel Golden (11 February 2000). "Home-Schooled Kids Defy Stereotypes, Ace SAT Test". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "Fostering Educational Innovation in Choice-Based Multi-Venue and Government Single-Venue Settings." (pp. 32 n.21; 35-36 n.27; 42 n.57; 44 n.66)

- ↑ Lines, Patricia M. "Homeschooling". Kidsource. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Lips, Dan; Feinberg, Evan (2008-04-03). "Homeschooling: A Growing Option in American Education". Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Rob Reich". Stanford.edu. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ The civic perils of homeschooling Author: Rob Reich Journal: Educational Leadership (Alexandria) Pub.: 2002-04 Volume: 59 Issue: 7 Pages: 56

- ↑ CEPM – Trends and Issues: School Choice

- ↑ Stevens, Mitchell L. (2001). Kingdom of Children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeshcooling Movement (PDF). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691114682.

- ↑ Sizer, Bridget Bentz. "Socialization: Tackling Homeschooling's "S" word". pbsparents.

- ↑ Rose, Lowell C.; Alec M. Gallup; Stanley M. Elam (1997). "The 29th Annual Phi Delta Kappa/Gallup Poll of the Public's Attitudes Toward the Public Schools". Phi Delta Kappan. 1 79: 41–56.

- ↑ Gallup, Alec M.; Elam M. Stanley (1988). "The 20th Annual Gallup Poll of the Public's Attitudes Toward the Public Schools". Phi Delta Kappan 70 (1): 33–46.

- ↑ Spiegler, Thomas (2003). "Home education in Germany: An overview of the contemporary situation" (PDF). Evaluation and Research in Education 17 (2–3): 179–90. doi:10.1080/09500790308668301.

- ↑ "Home-school ban in Sweden forces families to mull leaving". The Washington Times. July 18, 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

External links

| Look up homeschooling in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Homeschooling |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A history of the modern homeschool movement, from the Cato Institute.

- National Home Education Research Institute NHERI produces research about homeschooling and sponsors the peer-reviewed academic journal Homeschool Researcher.

- The National Independent Study Accreditation Council

- International Center for Home Education Research Reviews

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||