Holocaust tourism

Holocaust tourism is travel to areas connected to the extermination of Jews during World War II. It typically includes visiting sites such as former Nazi concentration camps. It is a type of dark tourism.

The word holocaust is derived from the Greek word holokauston (meaning a completely burnt offering to God). It has come to be associated with the systematic extermination of approximately six million European Jews by the Nazi regime from 1933 to 1945,[1] although some researchers argue that the term should include the estimated five to seven million others who were also exterminated by the Nazis.[2] The term holocaust became widely used in 1950, when American researchers drew public attention to this phenomenon.

Seven dark suppliers

According to P.R. Stone, there is a dark tourism spectrum, which differentiates between the shades of dark tourism:[3]

darkest |

darker | dark | light | lighter | lightest |

The spectrum aids in identifying the intensity of both supply and consumption. Darkest tourism is characterized by the following elements: education orientation, historic background, location authenticity, non purposefulness, and poor tourism infrastructure. While the objects of lightest tourism have mostly opposite features: entertainment orientation, commercial centralization, inauthenticity, purposefulness, higher level of tourism infrastructure.

Professor William F.S. Miles stipulates that death and violent events, transmitted between generations through survivors and witnesses, are darker than other events. Miles also notes that the level of darkness of a tourist product may partially depend product on the perception of potential tourists.

Stone distinguishes seven dark suppliers, which create the dark tourism product. The model of seven dark suppliers demonstrate dark tourism as multi-faceted phenomenon, the following supply spectrum:[4]

- Dark Fun Factories. This category includes tourist sites which emphasize entertainment and a commercial ethic, e.g. The London Dungeon.

- Dark Exhibitions. These focus on exhibits associated with death and suffering. These exhibitions have an educational, reflective character, e.g. the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Dark Dungeons. This group includes prisons and courthouses, such as the Bodmin Jail Center.

- Dark Resting Places. Cemeteries of famous people, for example, the cemetery Pere-Lachaise in Paris.

- Dark Shrines. Sites which are remembrances and out of respect to the dead. Usually, Dark Shrines situated near to a former place of death, and are more permanent than Dark Exhibitions. An example would be the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin.

- Dark Conflict Sites. War sites and battlefields as tourist products, for instance the Guadalcanal Battlefield in the Solomon Islands from the Second World War.

- Dark Camps of Genocide. Sites where genocide and violence were actually perpetrated. Such sites belong to the darkest tourism. Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest of the Nazi Death Camps in World War II, is an example of this category. Holocaust sites depend on a government's political ideology.

Postmemory and Jewish identity

Holocaust tourism sites are related to postmemory and cultural identity, with postmemory being an important element in the motivations of holocaust tourists. Marianne Hirsch defines it as:

Postmemory characterizes the experience of those who grow up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are evacuated by the stories of the previous generation shaped by traumatic events that can be neither understood nor recreated.[5]

Postmemory is an interrelation between survivors and post-Holocaust generations, to save and transmit the Holocaust experience. The first studies regarding the second generation began to appear in the 1970s. For example, Helen Epstein's 1979 book Children of the Holcaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors consists of interviews with survivors' children from all over the world.

Some survivors' children's identities are dependent on their parents' Holocaust experience, resulting in some members of the second generation experiencing trans-generational trauma. Jewish visits to Holocaust sites are often efforts to explore the origins of their identity. Erica Lehrer considers this Jewish identity quest as "a way to step into the flow of family, community, and history from which one feels displaced".[6] Many Jewish tours are made to establish a connection of survivors and second generation with an unknown place and or identity.

Virtual Jewish communities

There are three communities on the internet in which Jewish related concerns and news are disseminated, particularly regarding holocaust tourism in Germany and Eastern Europe. As described by J.S. Podoshen and J.M. Hunt they are:

- Jewish Current Events. A primarily North American and Israeli forum with thousands of postings concerning world events, as well as Jewish-related news from global Jewish periodicals.

- Religious Judaism. A community of over four thousands American orthodox and conservative Jews, whose main interest is Judaism and its spread throughout the world. The community is subdivided into groups based on geographic areas. The group has published over one million posts, and according to the community's archive, the Holocaust in relation to tourism is one of the most discussed topics.

- Israeli News and Opinion. A site made up of Jews living in and near Israel, which discusses news from popular Israeli and Jewish press sources.

Holocaust tourism in Eastern Europe

During the last 20 years Eastern Europe has become the most popular region for Jewish heritage travels. The recent increase in tourism is due to several historic events which have opened the region: Poland's Solidarity movement; Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of glasnost and perestroika; and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Though many of the tourists have no direct experience of the Holocaust, many holocaust tours visit authentic Holocaust sites, such as cemeteries and crematoria. Two principal destinations of Holocaust tourism are Poland and Israel. The relationship between these two countries in holocaust tourism is best illustrated by the anthropologist Jack Kugelmass:

The death camps in Poland act as condensation symbols for the entire Jewish past, while Israel, the end point of the journey, is schematized as a Jewish future.

In Israel, the March of the Living (MOTL) was established in 1988, which organizes Holocaust tours for teenagers. Annually, MOTL sends thousands of young people from more than fifty countries to Poland and Israel.

Poland is one of the countries most visited by Holocaust tourists due to the number of death camps in Poland. Prior to World War II, Poland had the largest Jewish community in Europe, of which three million (90%) were murdered in the camps during the war.

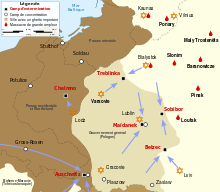

Death and labor camps were built in the late 1930s and early 1940s in Eastern Europe, many constructed in Poland, of which Auschwitz was the first and largest. In the period 1941-1945 other death camps were established in Poland, including:

- Majdanek (in Lublin);

- Birkenau (in Brzezinka);

- Treblinka (near the village of Treblinka);

- Bełżec (in Lublin);

- Sobibór (near the village of Sobibor);

- Chełmno (near the village of Chełmno nad Nerem)

Quest tourism

Quest tourism is a type of ethnographic tourism, focused on Jewish heritage and their extermination as a tragedy. This term was first used by E. Lehrer.[7] It is different from holocaust tourism because of its orientation to the tragic aspect of Jewish Heritage. Quest tourists have specific motivations and may be characterized by the following features:

- they are, as a rule, descendants of Holocaust survivors;

- they travel individually or with close friends and family;

- they are highly interested in travel;

- they possess strong postmemory;

- their goal is to reveal the story and overcome the communal ideology.

Critical view

Holocaust tourism, despite its short existence, has come under criticism. Polish journalist Konstanty Gebert noted:

People tend to forget that the important thing about Polish Jews is not that they waited 900 years for the Germans to come and kill them, but that they actually did something for those 900 years.

This implies, that tourists to Poland might pay too much attention to Holocaust sites. Anthropologist Jack Kugelmass wrote that tourists who visit Holocaust sites are more interested in death than in life.

Another criticism of this growing industry concerns its economic aspect, prompting Rabbi S. Aviner to suggest that Holocaust tourism to Poland "provide[s] livelihood to murderers".[8] Another famous rabbi, Z. Melamed, claims that Jews should refuse the trip to Poland, even if they wish to participate in the March of the Living.

Additionally, there are many posters which ask people to consider Eastern Europe as an anti-Semitic location. For example, one poster states:

Stop paying your enemies to display our horror. Without the support of Jews they'd go broke. Film it, watch it (in the movies and films), but don't give a penny to the (expletive) Poles.

See also

- Dark tourism

- Jewish History

Notes

- ↑ Holocaust museum Houston

- ↑ Friedlander, Henry (1995). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 191.

- ↑ P. R. Stone. A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibition. — Vol. 54, No. 2, 2006. — p.151

- ↑ P. R. Stone. A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibition. — Vol. 54, No. 2, 2006. — p.152

- ↑ Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory. New York: CreateSpace, 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Lehrer, Erica T. Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013, p. 101.

- ↑ Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

- ↑ J.S. Podoshen, J.M. Hunt. Equity restoration, the Holocaust and tourism of sacred sites. — Elsevier, 2011.p.1335

References

- Erica Lehrer. The Quest: Scratching the Heart // Poland Revisited. — Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2013. — pp. 91-122.

- E. Jilovsky. Recreating Postmemory? Children of Holocaust Survivors and the Journey to Auschwitz. — Monash University, 2008. — pp. 145-162.

- P. R. Stone. A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibition. — Vol. 54, No. 2, 2006. — pp. 145-160

- A. Jankowska, S. Müller-Pohl, E. Street. A Kosher Shrimp? The New Museum in the Context of Holocaust Tourism in Poland. — Poland, 2008.

- C. Aviv, D. Shneer. New Jews: The end of the Jewish Diaspora. — New York University, 2005. — pp. 215.

- J.S. Podoshen, J.M. Hunt. Equity restoration, the Holocaust and tourism of sacred sites. — Elsevier, 2011. pp. 1332- 1342.

- "W.Miles". Auschwitzt: Museum Interpretation and Darker Tourism. USA, 2002. pp.1175-1178.

Further reading

- T. Richmond. Konin: One Man’s Quest for a Vanished Jewish Community. — Vintage, 1996. — 572 pp.

- H. Epstein. Children of the Holocaust: conversations with sons and daughters of survivors. — Putnam, 1979. — 348 pp.

- J. Benstock. Film “The Holocaust Tourism”. — UK, 2005.

- T.P. Thurnell-Read. Engaging Auschwitz: an analysis of young travellers' experiences of Holocaust Tourism.// Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice. — 2009. — V.1. — №1. — pp. 26–52. — ISSN 1757-031X.

- J.Feldman. Above the Death Pits, Beneath the Flag. — Britain, 2008. — 95 pp.

External links

- Jewish Heritage Tours

- Poland Jewish Heritage Tours

- Quest for family

- Jewish currents

- Orthodox Judaism - The Orthodox Union

- Israeli News and Opinion

- History and meaning of the world "Holocaust"

- Vocabulary terms related to the Holocaust