History of tobacco

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

| History |

| Biology |

| Personal and Social impact |

| Production |

Tobacco has a long history from its usages in the early Americas. It became increasingly popular with the arrival of the Europeans by whom it was heavily traded. Following the industrial revolution, cigarettes were becoming popularized in the New World as well as Europe, which fostered yet another unparalleled increase in growth. This remained so until the scientific revelations in the mid-1900s.

Early history

Tobacco had already long been used in the Americas by the time European settlers arrived and introduced the practice to Europe, where it became popular. At high doses, tobacco can become hallucinogenic;[1] accordingly, Native Americans did not always use the drug recreationally. Instead, it was often consumed as an entheogen; among some tribes, this was done only by experienced shamans or medicine men. Eastern North American tribes would carry large amounts of tobacco in pouches as a readily accepted trade item and would often smoke it in pipes, either in defined ceremonies that were considered sacred, or to seal a bargain,[2] and they would smoke it at such occasions in all stages of life, even in childhood.[3] It was believed that tobacco was a gift from the Creator and that the exhaled tobacco smoke was capable of carrying one's thoughts and prayers to heaven.[4]

Apart from smoking, tobacco had a number of uses as medicine. As a pain killer it was used for earache and toothache and occasionally as a poultice. Smoking was said by the desert Indians to be a cure for colds, especially if the tobacco was mixed with the leaves of the small desert sage, Salvia dorrii, or the root of Indian balsam or cough root, Leptotaenia multifida, the addition of which was thought to be particularly good for asthma and tuberculosis.[5] Uncured tobacco was often eaten, used in enemas, or drunk as extracted juice. Early missionaries often reported on the ecstatic state caused by tobacco. As its use spread into Western cultures, however, it was no longer used primarily for entheogenic or religious purposes, although religious use of tobacco is still common among many indigenous peoples, particularly in the Americas. Among the Cree and Ojibway of Canada and the north-central United States, it is offered to the Creator, with prayers, and is used in sweat lodges, pipe ceremonies, smudging, and is presented as a gift. A gift of tobacco is tradition when asking an Ojibway elder a question of a spiritual nature. Because of its sacred nature, tobacco abuse (thoughtlessly and addictively chain smoking) is seriously frowned upon by the Algonquian tribes of Canada, as it is believed that if one so abuses the plant, it will abuse that person in return, causing sickness. The proper and traditional native way of offering the smoke is said to involve directing it toward the four cardinal points (north, south, east, and west), rather than holding it deeply within the lungs for prolonged periods.[6]

European discovery

Las Casas vividly described how the first scouts sent by Columbus into the interior of Cuba found

men with half-burned wood in their hands and certain herbs to take their smokes, which are some dry herbs put in a certain leaf, also dry, like those the boys make on the day of the Passover of the Holy Ghost; and having lighted one part of it, by the other they suck, absorb, or receive that smoke inside with the breath, by which they become benumbed and almost drunk, and so it is said they do not feel fatigue. These, muskets as we will call them, they call tabacos. I knew Spaniards on this island of Española who were accustomed to take it, and being reprimanded for it, by telling them it was a vice, they replied they were unable to cease using it. I do not know what relish or benefit they found in it.[7]

Rodrigo de Jerez was one of the Spanish crewmen who sailed to the Americas on the Santa Maria as part of Christopher Columbus's first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492. He is credited with being the first European smoker.

Following the arrival of Europeans, tobacco became one of the primary products fueling colonization, and also became a driving factor in the incorporation of African slave labor. The Spanish introduced tobacco to Europeans in about 1528, and by 1533, Diego Columbus mentioned a tobacco merchant of Lisbon in his will, showing how quickly the traffic had sprung up. Nicot, French ambassador in Lisbon, sent samples to Paris in 1559. The French, Spanish, and Portuguese initially referred to the plant as the "sacred herb" because of its valuable medicinal properties.[7] In 1571, a Spanish doctor named Nicolas Monardes wrote a book about the history of medicinal plants of the new world. In this he claimed that tobacco could cure 36 health problems.[8]

Sir Walter Raleigh is credited with taking the first "Virginia" tobacco to Europe, referring to it as tobah as early as 1578. In 1595 Anthony Chute published Tabaco, which repeated earlier arguments about the benefits of the plant and emphasised the health-giving properties of pipe-smoking.

The importation of tobacco into Europe was not without resistance and controversy in the 17th century. Stuart King James I wrote a famous polemic titled A Counterblaste to Tobacco in 1604, in which the king denounced tobacco use as "[a] custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse." In that same year, an English statute was enacted that placed a heavy protective tariff on every pound of tobacco brought into England.[9]

The Japanese were introduced to tobacco by Portuguese sailors from 1542.

Tobacco first arrived in the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century,[10] where it attracted the attention of doctors[11] and became a commonly prescribed medicine for many ailments. Although tobacco was initially prescribed as medicine, further study led to claims that smoking caused dizziness, fatigue, dulling of the senses, and a foul taste/odour in the mouth.[12]

Sultan Murad IV banned smoking in the Ottoman Empire in 1633, and the offense was punishable by death.[13] When the ban was lifted by his successor, Ibrahim the Mad, it was instead taxed. In 1682, Damascene jurist Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi declared: "Tobacco has now become extremely famous in all the countries of Islam ... People of all kinds have used it and devoted themselves to it ... I have even seen young children of about five years applying themselves to it."[14] In 1750, a Damascene townsmen observed "a number of women greater than the men, sitting along the bank of the Barada River. They were eating and drinking, and drinking coffee and smoking tobacco just as the men were doing."[14]

Tobacco smoking first reached Australian shores when it was introduced to northern-dwelling Indigenous communities by visiting Indonesian fishermen in the early 18th century. British patterns of tobacco use were transported to Australia along with the new settlers in 1788; and in the years following colonisation, British smoking behaviour was rapidly adopted by Indigenous people as well. By the early 19th century tobacco was an essential commodity routinely issued to servants, prisoners and ticket-of-leave men (conditionally released convicts) as an inducement to work, or conversely, withheld as a means of punishment.[15]

Plantations in Virginia

.jpg)

In 1609, English colonist John Rolfe arrived at Jamestown, Virginia, and became the first settler to successfully raise tobacco (commonly referred to at that time as "brown gold")[16] for commercial use. The tobacco raised in Virginia at that time, Nicotiana rustica, did not suit European tastes, but Rolfe raised a more popular variety, Nicotiana tabacum, from seeds brought with him from Bermuda. Tobacco was used as currency by the Virginia settlers for years, and Rolfe was able to make his fortune in farming it for export at Varina Farms Plantation.

When he left for England with his wife, Pocahontas a daughter of Chief Powhatan, he had become wealthy. Returning to Jamestown, following Pocahontas' death in England, Rolfe continued in his efforts to improve the quality of commercial tobacco, and, by 1620, 40,000 pounds (18,000 kg) of tobacco were shipped to England. By the time John Rolfe died in 1622, Jamestown was thriving as a producer of tobacco, and its population had topped 4,000. Tobacco led to the importation of the colony's first black slaves in 1619. In the year 1616, 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) of tobacco were produced in Jamestown, Virginia, quickly rising up to 119,000 pounds (54,000 kg) in 1620.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, tobacco continued to be the cash crop of the Virginia Colony, as well as The Carolinas. Large tobacco warehouses filled the areas near the wharves of new, thriving towns such as Dumfries on the Potomac, Richmond and Manchester at the fall line (head of navigation) on the James, and Petersburg on the Appomattox.

Modern history

A historian of the American South in the late 1860s reported on typical usage in the region where it was grown:[17]

The chewing of tobacco was well-nigh universal. This habit had been widespread among the agricultural population of America both North and South before the war. Soldiers had found the quid a solace in the field and continued to revolve it in their mouths upon returning to their homes. Out of doors where his life was principally led the chewer spat upon his lands without offence to other men, and his homes and public buildings were supplied with spittoons. Brown and yellow parabolas were projected to right and left toward these receivers, but very often without the careful aim which made for clean living. Even the pews of fashionable churches were likely to contain these familiar conveniences. The large numbers of Southern men, and these were of the better class (officers in the Confederate army and planters, worth $20,000 or more, and barred from general amnesty) who presented themselves for the pardon of President Johnson, while they sat awaiting his pleasure in the ante-room at the White House, covered its floor with pools and rivulets of their spittle. An observant traveller in the South in 1865 said that in his belief seven-tenths of all persons above the age of twelve years, both male and female, used tobacco in some form. Women could be seen at the doors of their cabins in their bare feet, in their dirty one-piece cotton garments, their chairs tipped back, smoking pipes made of corn cobs into which were fitted reed stems or goose quills. Boys of eight or nine years of age and half-grown girls smoked. Women and girls "dipped" in their houses, on their porches, in the public parlors of hotels and in the streets.

Until 1883, tobacco excise tax accounted for one third of internal revenue collected by the United States government. Internal Revenue Service data for 1879-80 show total tobacco tax receipts of $38.9 million, out of total receipts of $116.8 million.[18] Following the American Civil War, the tobacco industry struggled as it attempted to adapt. Not only did the labor force change from slavery to sharecropping, but a change in demand also occurred. As in Europe, there was a desire for not only snuff, pipes and cigars, but cigarettes appeared as well.

With a change in demand and a change in labor force, James Bonsack, an avid craftsman, in 1881 created a machine that revolutionized cigarette production. The machine chopped the tobacco, then dropped a certain amount of the tobacco into a long tube of paper, which the machine would then roll and push out the end where it would be sliced by the machine into individual cigarettes. This machine operated at thirteen times the speed of a human cigarette roller.[19]

This caused an enormous growth in the tobacco industry, that lasted well into the 20th century, until the scientific revelations discovering health consequences of smoking,[20] and tobacco companies adding chemical additives were revealed.

In the United States, The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act) became law in 2009. It gave the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products to protect public health.[21]

Health concerns

Nazi Germany saw the first modern anti-smoking campaign,[22] the National Socialist government condemning tobacco use,[23] funding research against it,[24] levying increasing sin taxes on it,[25] and in 1941 tobacco was banned in various public places as a health hazard. The anti-tobacco campaign was also associated with racism and antisemitism, Jews being blamed for its initial import, and the need to keep the "Master Race" healthy being cited for the effort to squelch its use.

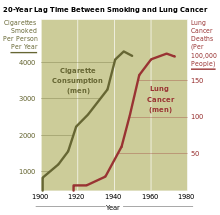

In the UK and the USA, an increase in lung cancer rates was being picked up by the 1930s, but the cause for this increase remained debated and unclear.[26]

A true breakthrough came in 1948, when the British physiologist Richard Doll published the first major studies that proved that smoking could cause serious health damage.[27][28] In 1950, he published research in the British Medical Journal that showed a close link between smoking and lung cancer.[29] Four years later, in 1954 the British Doctors Study, a study of some 40 thousand doctors over 20 years, confirmed the suggestion, based on which the government issued advice that smoking and lung cancer rates were related.[30] The British Doctors Study lasted till 2001, with result published every ten years and final results published in 2004 by Doll and Richard Peto.[31] Much early research was also done by Dr. Ochsner. Reader's Digest magazine for many years published frequent anti-smoking articles.

In 1964 the United States Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health likewise began suggesting the relationship between smoking and cancer, which confirmed its suggestions 20 years later in the 1980s.

Partial controls and regulatory measures eventually followed in much of the developed world, including partial advertising bans, minimum age of sale requirements, and basic health warnings on tobacco packaging. However, smoking prevalence and associated ill health continued to rise in the developed world in the first three decades following Richard Doll's discovery, with governments sometimes reluctant to curtail a habit seen as popular as a result - and increasingly organised disinformation efforts by the tobacco industry and their proxies (covered in more detail below). Realisation dawned gradually that the health effects of smoking and tobacco use were susceptible only to a multi-pronged policy response which combined positive health messages with medical assistance to cease tobacco use and effective marketing restrictions, as initially indicated in a 1962 overview by the British Royal College of Physicians[32] and the 1964 report of the U.S. Surgeon General.

In the 1950s tobacco companies engaged in a cigarette advertising war surrounding the tar content in cigarettes that came to be known as the tar derby. The companies repositioned their brands to emphasize low tar content, filter technology and nicotine levels. The period ended in 1959 after the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairman and several cigarette company presidents agreed to discontinue usage of tar or nicotine levels in advertisements.[33]

In order to reduce the potential burden of disease, the World Health Organization(WHO) successfully rallied 168 countries to sign the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003.[34] The Convention is designed to push for effective legislation and its enforcement in all countries to reduce the harmful effects of tobacco.

In science

The tobacco smoke enema was the principal medical method to resuscitate victims of drowning in the 18th century.

As a lucrative crop, tobacco has been the subject of a great deal of biological and genetic research. The economic impact of Tobacco Mosaic disease was the impetus that led to the isolation of Tobacco mosaic virus, the first virus to be identified; the fortunate coincidence that it is one of the simplest viruses and can self-assemble from purified nucleic acid and protein led, in turn, to the rapid advancement of the field of virology. The 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was shared by Wendell Meredith Stanley for his 1935 work crystallizing the virus and showing that it remains active.

References

Notes

- ↑ This Is Your Country on Drugs: The Secret History of Getting High in America, Ryan Grim, 2009.

- ↑ e.g. Heckewelder, History, Manners and Customs of the Indian Nations who Once Inhabited Pennsylvania, p. 149 ff.

- ↑ "They smoke with excessive eagerness ... men, women, girls and boys, all find their keenest pleasure in this way." - Dièreville describing the Mi'kmaq, c. 1699 in Port Royal.

- ↑ Tobacco: A Study of Its Consumption in the United States, Jack Jacob Gottsegen, 1940, p. 107.

- ↑ California Natural History Guides: 10. Early Uses of California Plant, By Edward K. Balls University of California Press, 1962 University of California Press.

- ↑ Aboriginal Youth Network / Health Canada, "A Tribe called Quit"

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico p. 768

- ↑ The History of Tobacco

- ↑ A Law of James about Tobacco

- ↑ Grehan, p.1

- ↑ Grehan, p.2

- ↑ Grehan, p.7

- ↑ 7 Historical Smoking Bans

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Grehan, p.3

- ↑ Tobacco in Australia

- ↑ Jamestown, Virginia: An Overview

- ↑ A History of the United States since the Civil War Volume: 1. by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer; 1917. P 93.

- ↑ 'The Republican Campaign Textbook, 1880.' Statistical Tables, P 207.

- ↑ Burns, p. 134.

- ↑ Burns, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/ucm246129.htm

- ↑ Szollosi-Janze 2001, p. 15

- ↑ Bynum et al. 2006, p. 375

- ↑ Proctor, Robert N. (1996), Nazi Medicine and Public Health Policy, Dimensions, Anti-Defamation League, archived from the original on 31 May 2008, retrieved 2008-06-01

- ↑ Robert N. Proctor, Pennsylvania State University (December 1996), "The anti-tobacco campaign of the Nazis: a little known aspect of public health in Germany, 1933-45", British Medical Journal 313 (7070): 1450–3, doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7070.1450, PMC 2352989, PMID 8973234, archived from the original on 19 May 2008, retrieved 2008-06-01

- ↑ Colin White (September 1989). "Research on Smoking and Lung Cancer: A Landmark in the History of Chronic Disease Epidemiology" (PDF). The Yale Journal Of Biology And Medicine 63 (1): 29–46. PMC 2589239. PMID 2192501.

- ↑ Sander L. Gilman and Zhou Xun, "Introduction" in Smoke, p. 25

- ↑ JM Appel. Smoke and Mirrors: One Case for Ethical Obligations of the Physician as Public Role Model Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, Volume 18, Issue 01, January 2009, pp 95-100.

- ↑ Doll, Rich; and Hilly, A. Bradford (30 September 1950). "Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report". British Medical Journal 2 (4682): 739–48. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4682.739. PMC 2038856. PMID 14772469.

- ↑ Doll Richard, Bradford Hilly A (26 June 1954). "The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. A preliminary report". British Medical Journal 1 (4877): 1451–55. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4877.1451. PMC 2085438. PMID 13160495.

- ↑ Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observation on male British doctors.". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

- ↑ Royal College of Physicians "Smoking and Health. Summary and report of the Royal College of Physicians of London on smoking in relation to cancer of the lung and other diseases"(1962)

- ↑ "TOBACCO: End of the Tar Derby". Time. 15 February 1960.

- ↑ WHO | WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC)

Bibliography

- Benedict, Carol. Golden-Silk Smoke: A History of Tobacco in China, 1550-2010 (2011)

- Brandt, Allan. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America (2007) (

- Breen, T. H. (1985). Tobacco Culture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00596-6. Source on tobacco culture in 18th-century Virginia pp. 46–55

- Burns, Eric. The Smoke of the Gods: A Social History of Tobacco. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007.

- Collins, W.K. and S.N. Hawks. "Principles of Flue-Cured Tobacco Production" 1st Edition, 1993

- Cosner, Charlotte. The Golden Leaf: How Tobacco Shaped Cuba and the Atlantic World (Vanderbilt University Press; 2015)

- Fuller, R. Reese (Spring 2003). Perique, the Native Crop. Louisiana Life.

- Gately, Iain. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Grove Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8021-3960-4.

- Goodman, Jordan. Tobacco in History:The Cultures of Dependence (1993), A scholarly history worldwide.

- Graves, John. "Tobacco that is not Smoked" in From a Limestone Ledge (the sections on snuff and chewing tobacco) ISBN 0-394-51238-3

- Grehan, James. Smoking and "Early Modern" Sociability: The Great Tobacco Debate in the Ottoman Middle East (Seventeenth to Eighteenth Centuries). The American Historical Review (2006) 3#5 online

- Hahn, Barbara. Making Tobacco Bright: Creating an American Commodity, 1617-1937 (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011) 248 pages; examines how marketing, technology, and demand figured in the rise of Bright Flue-Cured Tobacco, a variety first grown in the inland Piedmont region of the Virginia-North Carolina border.

- Killebrew, J. B. and Myrick, Herbert (1909). Tobacco Leaf: Its Culture and Cure, Marketing and Manufacture. Orange Judd Company. Source for flea beetle typology (p. 243)

- Kluger, Richard. Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War (1996), Pulitzer Prize

- Murphey, Rhoads. Studies on Ottoman Society and Culture: 16th-18th Centuries. Burlington, VT: Ashgate: Variorum, 2007 ISBN 978-0-7546-5931-0 ISBN 0-7546-5931-3

- Poche, L. Aristee (2002). Perique tobacco: Mystery and history.

- Price, Jacob M. "The rise of Glasgow in the Chesapeake tobacco trade, 1707-1775." William and Mary Quarterly (1954) pp: 179-199. in JSTOR

- Tilley, Nannie May The Bright Tobacco Industry 1860–1929 ISBN 0-405-04728-2.

- Schoolcraft, Henry R. Historical and Statistical Information respecting the Indian Tribes of the United States (Philadelphia, 1851–57)

- Shechter, Relli. Smoking, Culture and Economy in the Middle East: The Egyptian Tobacco Market 1850–2000. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2006 ISBN 1-84511-137-0

External links

- History of tobacco article from Big Site of Amazing Facts

- Boston University MedicalCenter

- History of Tobacco from License To Vape

- Tobacco in World War II