History of the Internet

| History of computing |

|---|

| Hardware |

| Software |

| Computer science |

| Modern concepts |

| Timeline of computing |

|

| Internet |

|---|

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet |

| Internet portal |

The history of the Internet begins with the development of electronic computers in the 1950s. Initial concepts of packet networking originated in several computer science laboratories in the United States, Great Britain, and France. The US Department of Defense awarded contracts as early as the 1960s for packet network systems, including the development of the ARPANET (which would become the first network to use the Internet Protocol.) The first message was sent over the ARPANET from computer science Professor Leonard Kleinrock's laboratory at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to the second network node at Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

Packet switching networks such as ARPANET, Mark I at NPL in the UK, CYCLADES, Merit Network, Tymnet, and Telenet, were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s using a variety of communications protocols. The ARPANET in particular led to the development of protocols for internetworking, in which multiple separate networks could be joined into a network of networks.

Access to the ARPANET was expanded in 1981 when the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the Computer Science Network (CSNET). In 1982, the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) was introduced as the standard networking protocol on the ARPANET. In the early 1980s the NSF funded the establishment for national supercomputing centers at several universities, and provided interconnectivity in 1986 with the NSFNET project, which also created network access to the supercomputer sites in the United States from research and education organizations. Commercial Internet service providers (ISPs) began to emerge in the late 1980s. The ARPANET was decommissioned in 1990. Private connections to the Internet by commercial entities became widespread quickly, and the NSFNET was decommissioned in 1995, removing the last restrictions on the use of the Internet to carry commercial traffic.

In the 1980s, the work of Tim Berners-Lee in the United Kingdom, on the World Wide Web, theorised the fact that protocols link hypertext documents into a working system,[1] marking the beginning the modern Internet. Since the mid-1990s, the Internet has had a revolutionary impact on culture and commerce, including the rise of near-instant communication by electronic mail, instant messaging, voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) telephone calls, two-way interactive video calls, and the World Wide Web with its discussion forums, blogs, social networking, and online shopping sites. The research and education community continues to develop and use advanced networks such as NSF's very high speed Backbone Network Service (vBNS), Internet2, and National LambdaRail. Increasing amounts of data are transmitted at higher and higher speeds over fiber optic networks operating at 1-Gbit/s, 10-Gbit/s, or more. The Internet's takeover of the global communication landscape was almost instant in historical terms: it only communicated 1% of the information flowing through two-way telecommunications networks in the year 1993, already 51% by 2000, and more than 97% of the telecommunicated information by 2007.[2] Today the Internet continues to grow, driven by ever greater amounts of online information, commerce, entertainment, and social networking.

| Internet history timeline |

|

Early research and development:

Merging the networks and creating the Internet:

Commercialization, privatization, broader access leads to the modern Internet:

Examples of popular Internet services:

Further information: Timeline of popular Internet services |

Precursors

The telegraph system is the first fully digital communication system. Thus the Internet has precursors, such as the telegraph system, that date back to the 19th century, more than a century before the digital Internet became widely used in the second half of the 1990s. The concept of data communication – transmitting data between two different places, connected via some kind of electromagnetic medium, such as radio or an electrical wire – predates the introduction of the first computers. Such communication systems were typically limited to point to point communication between two end devices. Telegraph systems and telex machines can be considered early precursors of this kind of communication.

Fundamental theoretical work in data transmission and information theory was developed by Claude Shannon, Harry Nyquist, and Ralph Hartley, during the early 20th century.

Early computers used the technology available at the time to allow communication between the central processing unit and remote terminals. As the technology evolved, new systems were devised to allow communication over longer distances (for terminals) or with higher speed (for interconnection of local devices) that were necessary for the mainframe computer model. Using these technologies made it possible to exchange data (such as files) between remote computers. However, the point to point communication model was limited, as it did not allow for direct communication between any two arbitrary systems; a physical link was necessary. The technology was also deemed as inherently unsafe for strategic and military use, because there were no alternative paths for the communication in case of an enemy attack.

Three terminals and an ARPA

A pioneer in the call for a global network, J. C. R. Licklider, proposed in his January 1960 paper, "Man-Computer Symbiosis": "A network of such [computers], connected to one another by wide-band communication lines [which provided] the functions of present-day libraries together with anticipated advances in information storage and retrieval and [other] symbiotic functions."[3]

In August 1962, Licklider and Welden Clark published the paper "On-Line Man-Computer Communication",[4] which was one of the first descriptions of a networked future.

In October 1962, Licklider was hired by Jack Ruina as director of the newly established Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) within DARPA, with a mandate to interconnect the United States Department of Defense's main computers at Cheyenne Mountain, the Pentagon, and SAC HQ. There he formed an informal group within DARPA to further computer research. He began by writing memos describing a distributed network to the IPTO staff, whom he called "Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network".[5] As part of the information processing office's role, three network terminals had been installed: one for System Development Corporation in Santa Monica, one for Project Genie at the University of California, Berkeley and one for the Compatible Time-Sharing System project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Licklider's identified need for inter-networking would be made obvious by the apparent waste of resources this caused.

For each of these three terminals, I had three different sets of user commands. So if I was talking online with someone at S.D.C. and I wanted to talk to someone I knew at Berkeley or M.I.T. about this, I had to get up from the S.D.C. terminal, go over and log into the other terminal and get in touch with them....

I said, oh man, it's obvious what to do: If you have these three terminals, there ought to be one terminal that goes anywhere you want to go where you have interactive computing. That idea is the ARPAnet.[6]

Although he left the IPTO in 1964, five years before the ARPANET went live, it was his vision of universal networking that provided the impetus that led his successors such as Lawrence Roberts and Robert Taylor to further the ARPANET development. Licklider later returned to lead the IPTO in 1973 for two years.[7]

Packet switching

At the tip of the problem lay the issue of connecting separate physical networks to form one logical network. In the 1960s, Paul Baran of the RAND Corporation produced a study of survivable networks for the U.S. military in the event of nuclear war.[9] Information transmitted across Baran's network would be divided into what he called "message-blocks". Independently, Donald Davies (National Physical Laboratory, UK), proposed and developed a similar network based on what he called packet-switching, the term that would ultimately be adopted. Leonard Kleinrock (MIT) developed a mathematical theory behind this technology. Packet-switching provides better bandwidth utilization and response times than the traditional circuit-switching technology used for telephony, particularly on resource-limited interconnection links.[10]

Packet switching is a rapid store and forward networking design that divides messages up into arbitrary packets, with routing decisions made per-packet. Early networks used message switched systems that required rigid routing structures prone to single point of failure. This led Tommy Krash and Paul Baran's U.S. military-funded research to focus on using message-blocks to include network redundancy.[11]

Networks that led to the Internet

ARPANET

Promoted to the head of the information processing office at Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), Robert Taylor intended to realize Licklider's ideas of an interconnected networking system. Bringing in Larry Roberts from MIT, he initiated a project to build such a network. The first ARPANET link was established between the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Stanford Research Institute at 22:30 hours on October 29, 1969.[12]

"We set up a telephone connection between us and the guys at SRI ...", Kleinrock ... said in an interview: "We typed the L and we asked on the phone,

- "Do you see the L?"

- "Yes, we see the L," came the response.

- We typed the O, and we asked, "Do you see the O."

- "Yes, we see the O."

- Then we typed the G, and the system crashed ...

Yet a revolution had begun" ....[13]

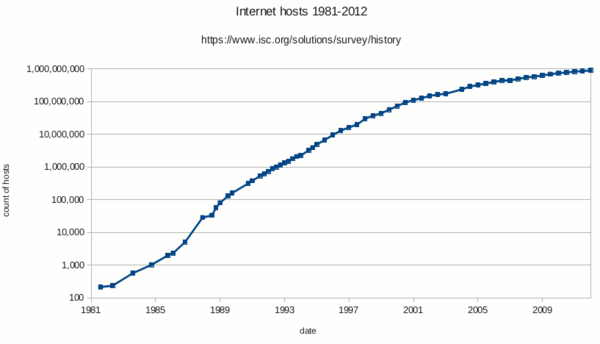

By December 5, 1969, a 4-node network was connected by adding the University of Utah and the University of California, Santa Barbara. Building on ideas developed in ALOHAnet, the ARPANET grew rapidly. By 1981, the number of hosts had grown to 213, with a new host being added approximately every twenty days.[14][15]

ARPANET development was centered around the Request for Comments (RFC) process, still used today for proposing and distributing Internet Protocols and Systems. RFC 1, entitled "Host Software", was written by Steve Crocker from the University of California, Los Angeles, and published on April 7, 1969. These early years were documented in the 1972 film Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing.

ARPANET became the technical core of what would become the Internet, and a primary tool in developing the technologies used. The early ARPANET used the Network Control Program (NCP, sometimes Network Control Protocol) rather than TCP/IP. On January 1, 1983, known as flag day, NCP on the ARPANET was replaced by the more flexible and powerful family of TCP/IP protocols, marking the start of the modern Internet.[16]

International collaborations on ARPANET were sparse. For various political reasons, European developers were concerned with developing the X.25 networks. Notable exceptions were the Norwegian Seismic Array (NORSAR) in 1972, followed in 1973 by Sweden with satellite links to the Tanum Earth Station and Peter Kirstein's research group in the UK, initially at the Institute of Computer Science, London University and later at University College London.[17]

NPL

In 1965, Donald Davies of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom) proposed a national data network based on packet-switching. The proposal was not taken up nationally, but by 1970 he had designed and built the Mark I packet-switched network to meet the needs of the multidisciplinary laboratory and prove the technology under operational conditions.[18] By 1976 12 computers and 75 terminal devices were attached and more were added until the network was replaced in 1986.

Merit Network

The Merit Network[19] was formed in 1966 as the Michigan Educational Research Information Triad to explore computer networking between three of Michigan's public universities as a means to help the state's educational and economic development.[20] With initial support from the State of Michigan and the National Science Foundation (NSF), the packet-switched network was first demonstrated in December 1971 when an interactive host to host connection was made between the IBM mainframe computer systems at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and Wayne State University in Detroit.[21] In October 1972 connections to the CDC mainframe at Michigan State University in East Lansing completed the triad. Over the next several years in addition to host to host interactive connections the network was enhanced to support terminal to host connections, host to host batch connections (remote job submission, remote printing, batch file transfer), interactive file transfer, gateways to the Tymnet and Telenet public data networks, X.25 host attachments, gateways to X.25 data networks, Ethernet attached hosts, and eventually TCP/IP and additional public universities in Michigan join the network.[21][22] All of this set the stage for Merit's role in the NSFNET project starting in the mid-1980s.

CYCLADES

The CYCLADES packet switching network was a French research network designed and directed by Louis Pouzin. First demonstrated in 1973, it was developed to explore alternatives to the initial ARPANET design and to support network research generally. It was the first network to make the hosts responsible for the reliable delivery of data, rather than the network itself, using unreliable datagrams and associated end-to-end protocol mechanisms.[23][24]

X.25 and public data networks

Based on ARPA's research, packet switching network standards were developed by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in the form of X.25 and related standards. While using packet switching, X.25 is built on the concept of virtual circuits emulating traditional telephone connections. In 1974, X.25 formed the basis for the SERCnet network between British academic and research sites, which later became JANET. The initial ITU Standard on X.25 was approved in March 1976.[25]

The British Post Office, Western Union International and Tymnet collaborated to create the first international packet switched network, referred to as the International Packet Switched Service (IPSS), in 1978. This network grew from Europe and the US to cover Canada, Hong Kong, and Australia by 1981. By the 1990s it provided a worldwide networking infrastructure.[26]

Unlike ARPANET, X.25 was commonly available for business use. Telenet offered its Telemail electronic mail service, which was also targeted to enterprise use rather than the general email system of the ARPANET.

The first public dial-in networks used asynchronous TTY terminal protocols to reach a concentrator operated in the public network. Some networks, such as CompuServe, used X.25 to multiplex the terminal sessions into their packet-switched backbones, while others, such as Tymnet, used proprietary protocols. In 1979, CompuServe became the first service to offer electronic mail capabilities and technical support to personal computer users. The company broke new ground again in 1980 as the first to offer real-time chat with its CB Simulator. Other major dial-in networks were America Online (AOL) and Prodigy that also provided communications, content, and entertainment features. Many bulletin board system (BBS) networks also provided on-line access, such as FidoNet which was popular amongst hobbyist computer users, many of them hackers and amateur radio operators.

UUCP and Usenet

In 1979, two students at Duke University, Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis, originated the idea of using Bourne shell scripts to transfer news and messages on a serial line UUCP connection with nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Following public release of the software, the mesh of UUCP hosts forwarding on the Usenet news rapidly expanded. UUCPnet, as it would later be named, also created gateways and links between FidoNet and dial-up BBS hosts. UUCP networks spread quickly due to the lower costs involved, ability to use existing leased lines, X.25 links or even ARPANET connections, and the lack of strict use policies compared to later networks like CSNET and Bitnet. All connects were local. By 1981 the number of UUCP hosts had grown to 550, nearly doubling to 940 in 1984. – Sublink Network, operating since 1987 and officially founded in Italy in 1989, based its interconnectivity upon UUCP to redistribute mail and news groups messages throughout its Italian nodes (about 100 at the time) owned both by private individuals and small companies. Sublink Network represented possibly one of the first examples of the internet technology becoming progress through popular diffusion.[27]

Merging the networks and creating the Internet (1973–90)

TCP/IP

With so many different network methods, something was needed to unify them. Robert E. Kahn of DARPA and ARPANET recruited Vinton Cerf of Stanford University to work with him on the problem. By 1973, they had worked out a fundamental reformulation, where the differences between network protocols were hidden by using a common internetwork protocol, and instead of the network being responsible for reliability, as in the ARPANET, the hosts became responsible. Cerf credits Hubert Zimmermann, Gerard LeLann and Louis Pouzin (designer of the CYCLADES network) with important work on this design.[28]

The specification of the resulting protocol, RFC 675 – Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program, by Vinton Cerf, Yogen Dalal and Carl Sunshine, Network Working Group, December 1974, contains the first attested use of the term internet, as a shorthand for internetworking; later RFCs repeat this use, so the word started out as an adjective rather than the noun it is today.

With the role of the network reduced to the bare minimum, it became possible to join almost any networks together, no matter what their characteristics were, thereby solving Kahn's initial problem. DARPA agreed to fund development of prototype software, and after several years of work, the first demonstration of a gateway between the Packet Radio network in the SF Bay area and the ARPANET was conducted by the Stanford Research Institute. On November 22, 1977 a three network demonstration was conducted including the ARPANET, the SRI's Packet Radio Van on the Packet Radio Network and the Atlantic Packet Satellite network.[29][30]

Stemming from the first specifications of TCP in 1974, TCP/IP emerged in mid-late 1978 in nearly final form. By 1981, the associated standards were published as RFCs 791, 792 and 793 and adopted for use. DARPA sponsored or encouraged the development of TCP/IP implementations for many operating systems and then scheduled a migration of all hosts on all of its packet networks to TCP/IP. On January 1, 1983, known as flag day, TCP/IP protocols became the only approved protocol on the ARPANET, replacing the earlier NCP protocol.[31]

From ARPANET to NSFNET

After the ARPANET had been up and running for several years, ARPA looked for another agency to hand off the network to; ARPA's primary mission was funding cutting edge research and development, not running a communications utility. Eventually, in July 1975, the network had been turned over to the Defense Communications Agency, also part of the Department of Defense. In 1983, the U.S. military portion of the ARPANET was broken off as a separate network, the MILNET. MILNET subsequently became the unclassified but military-only NIPRNET, in parallel with the SECRET-level SIPRNET and JWICS for TOP SECRET and above. NIPRNET does have controlled security gateways to the public Internet.

The networks based on the ARPANET were government funded and therefore restricted to noncommercial uses such as research; unrelated commercial use was strictly forbidden. This initially restricted connections to military sites and universities. During the 1980s, the connections expanded to more educational institutions, and even to a growing number of companies such as Digital Equipment Corporation and Hewlett-Packard, which were participating in research projects or providing services to those who were.

Several other branches of the U.S. government, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Department of Energy (DOE) became heavily involved in Internet research and started development of a successor to ARPANET. In the mid-1980s, all three of these branches developed the first Wide Area Networks based on TCP/IP. NASA developed the NASA Science Network, NSF developed CSNET and DOE evolved the Energy Sciences Network or ESNet.

NASA developed the TCP/IP based NASA Science Network (NSN) in the mid-1980s, connecting space scientists to data and information stored anywhere in the world. In 1989, the DECnet-based Space Physics Analysis Network (SPAN) and the TCP/IP-based NASA Science Network (NSN) were brought together at NASA Ames Research Center creating the first multiprotocol wide area network called the NASA Science Internet, or NSI. NSI was established to provide a totally integrated communications infrastructure to the NASA scientific community for the advancement of earth, space and life sciences. As a high-speed, multiprotocol, international network, NSI provided connectivity to over 20,000 scientists across all seven continents.

In 1981 NSF supported the development of the Computer Science Network (CSNET). CSNET connected with ARPANET using TCP/IP, and ran TCP/IP over X.25, but it also supported departments without sophisticated network connections, using automated dial-up mail exchange.

Its experience with CSNET lead NSF to use TCP/IP when it created NSFNET, a 56 kbit/s backbone established in 1986, to supported the NSF sponsored supercomputing centers. The NSFNET Project also provided support for the creation of regional research and education networks in the United States and for the connection of university and college campus networks to the regional networks.[32] The use of NSFNET and the regional networks was not limited to supercomputer users and the 56 kbit/s network quickly became overloaded. NSFNET was upgraded to 1.5 Mbit/s in 1988 under a cooperative agreement with the Merit Network in partnership with IBM, MCI, and the State of Michigan. The existence of NSFNET and the creation of Federal Internet Exchanges (FIXes) allowed the ARPANET to be decommissioned in 1990. NSFNET was expanded and upgraded to 45 Mbit/s in 1991, and was decommissioned in 1995 when it was replaced by backbones operated by several commercial Internet Service Providers.

Transition towards the Internet

The term "internet" was adopted in the first RFC published on the TCP protocol (RFC 675:[33] Internet Transmission Control Program, December 1974) as an abbreviation of the term internetworking and the two terms were used interchangeably. In general, an internet was any network using TCP/IP. It was around the time when ARPANET was interlinked with NSFNET in the late 1980s, that the term was used as the name of the network, Internet, being the large and global TCP/IP network.[34]

As interest in networking grew and new applications for it were developed, the Internet's technologies spread throughout the rest of the world. The network-agnostic approach in TCP/IP meant that it was easy to use any existing network infrastructure, such as the IPSS X.25 network, to carry Internet traffic. In 1984, University College London replaced its transatlantic satellite links with TCP/IP over IPSS.[35]

Many sites unable to link directly to the Internet created simple gateways for the transfer of electronic mail, the most important application of the time. Sites with only intermittent connections used UUCP or FidoNet and relied on the gateways between these networks and the Internet. Some gateway services went beyond simple mail peering, such as allowing access to File Transfer Protocol (FTP) sites via UUCP or mail.[36]

Finally, routing technologies were developed for the Internet to remove the remaining centralized routing aspects. The Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) was replaced by a new protocol, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). This provided a meshed topology for the Internet and reduced the centric architecture which ARPANET had emphasized. In 1994, Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) was introduced to support better conservation of address space which allowed use of route aggregation to decrease the size of routing tables.[37]

TCP/IP goes global (1989–2010)

CERN, the European Internet, the link to the Pacific and beyond

Between 1984 and 1988 CERN began installation and operation of TCP/IP to interconnect its major internal computer systems, workstations, PCs and an accelerator control system. CERN continued to operate a limited self-developed system (CERNET) internally and several incompatible (typically proprietary) network protocols externally. There was considerable resistance in Europe towards more widespread use of TCP/IP, and the CERN TCP/IP intranets remained isolated from the Internet until 1989.

In 1988, Daniel Karrenberg, from Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI) in Amsterdam, visited Ben Segal, CERN's TCP/IP Coordinator, looking for advice about the transition of the European side of the UUCP Usenet network (much of which ran over X.25 links) over to TCP/IP. In 1987, Ben Segal had met with Len Bosack from the then still small company Cisco about purchasing some TCP/IP routers for CERN, and was able to give Karrenberg advice and forward him on to Cisco for the appropriate hardware. This expanded the European portion of the Internet across the existing UUCP networks, and in 1989 CERN opened its first external TCP/IP connections.[38] This coincided with the creation of Réseaux IP Européens (RIPE), initially a group of IP network administrators who met regularly to carry out coordination work together. Later, in 1992, RIPE was formally registered as a cooperative in Amsterdam.

At the same time as the rise of internetworking in Europe, ad hoc networking to ARPA and in-between Australian universities formed, based on various technologies such as X.25 and UUCPNet. These were limited in their connection to the global networks, due to the cost of making individual international UUCP dial-up or X.25 connections. In 1989, Australian universities joined the push towards using IP protocols to unify their networking infrastructures. AARNet was formed in 1989 by the Australian Vice-Chancellors' Committee and provided a dedicated IP based network for Australia.

The Internet began to penetrate Asia in the late 1980s. Japan, which had built the UUCP-based network JUNET in 1984, connected to NSFNET in 1989. It hosted the annual meeting of the Internet Society, INET'92, in Kobe. Singapore developed TECHNET in 1990, and Thailand gained a global Internet connection between Chulalongkorn University and UUNET in 1992.[39]

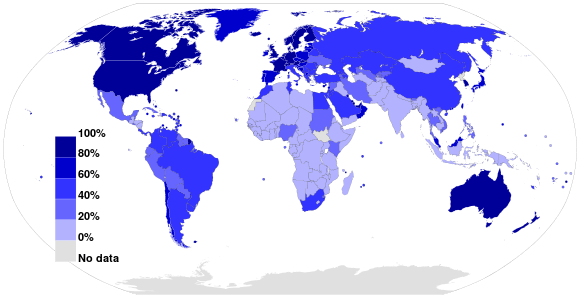

Global digital divide

as a percentage of a country's population

as a percentage of a country's population

While developed countries with technological infrastructures were joining the Internet, developing countries began to experience a digital divide separating them from the Internet. On an essentially continental basis, they are building organizations for Internet resource administration and sharing operational experience, as more and more transmission facilities go into place.

Africa

At the beginning of the 1990s, African countries relied upon X.25 IPSS and 2400 baud modem UUCP links for international and internetwork computer communications.

In August 1995, InfoMail Uganda, Ltd., a privately held firm in Kampala now known as InfoCom, and NSN Network Services of Avon, Colorado, sold in 1997 and now known as Clear Channel Satellite, established Africa's first native TCP/IP high-speed satellite Internet services. The data connection was originally carried by a C-Band RSCC Russian satellite which connected InfoMail's Kampala offices directly to NSN's MAE-West point of presence using a private network from NSN's leased ground station in New Jersey. InfoCom's first satellite connection was just 64 kbit/s, serving a Sun host computer and twelve US Robotics dial-up modems.

In 1996, a USAID funded project, the Leland Initiative, started work on developing full Internet connectivity for the continent. Guinea, Mozambique, Madagascar and Rwanda gained satellite earth stations in 1997, followed by Côte d'Ivoire and Benin in 1998.

Africa is building an Internet infrastructure. AfriNIC, headquartered in Mauritius, manages IP address allocation for the continent. As do the other Internet regions, there is an operational forum, the Internet Community of Operational Networking Specialists.[43]

There are many programs to provide high-performance transmission plant, and the western and southern coasts have undersea optical cable. High-speed cables join North Africa and the Horn of Africa to intercontinental cable systems. Undersea cable development is slower for East Africa; the original joint effort between New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) and the East Africa Submarine System (Eassy) has broken off and may become two efforts.[44]

Asia and Oceania

The Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC), headquartered in Australia, manages IP address allocation for the continent. APNIC sponsors an operational forum, the Asia-Pacific Regional Internet Conference on Operational Technologies (APRICOT).[45]

In 1991, the People's Republic of China saw its first TCP/IP college network, Tsinghua University's TUNET. The PRC went on to make its first global Internet connection in 1994, between the Beijing Electro-Spectrometer Collaboration and Stanford University's Linear Accelerator Center. However, China went on to implement its own digital divide by implementing a country-wide content filter.[46]

Latin America

As with the other regions, the Latin American and Caribbean Internet Addresses Registry (LACNIC) manages the IP address space and other resources for its area. LACNIC, headquartered in Uruguay, operates DNS root, reverse DNS, and other key services.

Opening the network to commerce

The interest in commercial use of the Internet became a hotly debated topic. Although commercial use was forbidden, the exact definition of commercial use could be unclear and subjective. UUCPNet and the X.25 IPSS had no such restrictions, which would eventually see the official barring of UUCPNet use of ARPANET and NSFNET connections. Some UUCP links still remained connecting to these networks however, as administrators cast a blind eye to their operation.

During the late 1980s, the first Internet service provider (ISP) companies were formed. Companies like PSINet, UUNET, Netcom, and Portal Software were formed to provide service to the regional research networks and provide alternate network access, UUCP-based email and Usenet News to the public. The first commercial dialup ISP in the United States was The World, which opened in 1989.[48]

In 1992, the U.S. Congress passed the Scientific and Advanced-Technology Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1862(g), which allowed NSF to support access by the research and education communities to computer networks which were not used exclusively for research and education purposes, thus permitting NSFNET to interconnect with commercial networks.[49][50] This caused controversy within the research and education community, who were concerned commercial use of the network might lead to an Internet that was less responsive to their needs, and within the community of commercial network providers, who felt that government subsidies were giving an unfair advantage to some organizations.[51]

By 1990, ARPANET had been overtaken and replaced by newer networking technologies and the project came to a close. New network service providers including PSINet, Alternet, CERFNet, ANS CO+RE, and many others were offering network access to commercial customers. NSFNET was no longer the de facto backbone and exchange point for Internet. The Commercial Internet eXchange (CIX), Metropolitan Area Exchanges (MAEs), and later Network Access Points (NAPs) were becoming the primary interconnections between many networks. The final restrictions on carrying commercial traffic ended on April 30, 1995 when the National Science Foundation ended its sponsorship of the NSFNET Backbone Service and the service ended.[52][53] NSF provided initial support for the NAPs and interim support to help the regional research and education networks transition to commercial ISPs. NSF also sponsored the very high speed Backbone Network Service (vBNS) which continued to provide support for the supercomputing centers and research and education in the United States.[54]

Networking in outer space

The first live Internet link into low earth orbit was established on January 22, 2010 when astronaut T. J. Creamer posted the first unassisted update to his Twitter account from the International Space Station, marking the extension of the Internet into space.[55] (Astronauts at the ISS had used email and Twitter before, but these messages had been relayed to the ground through a NASA data link before being posted by a human proxy.) This personal Web access, which NASA calls the Crew Support LAN, uses the space station's high-speed Ku band microwave link. To surf the Web, astronauts can use a station laptop computer to control a desktop computer on Earth, and they can talk to their families and friends on Earth using Voice over IP equipment.[56]

Communication with spacecraft beyond earth orbit has traditionally been over point-to-point links through the Deep Space Network. Each such data link must be manually scheduled and configured. In the late 1990s NASA and Google began working on a new network protocol, Delay-tolerant networking (DTN) which automates this process, allows networking of spaceborne transmission nodes, and takes the fact into account that spacecraft can temporarily lose contact because they move behind the Moon or planets, or because space weather disrupts the connection. Under such conditions, DTN retransmits data packages instead of dropping them, as the standard TCP/IP internet protocol does. NASA conducted the first field test of what it calls the "deep space internet" in November 2008.[57] Testing of DTN-based communications between the International Space Station and Earth (now termed Disruption-Tolerant Networking) has been ongoing since March 2009, and is scheduled to continue until March 2014.[58]

This network technology is supposed to ultimately enable missions that involve multiple spacecraft where reliable inter-vessel communication might take precedence over vessel-to-earth downlinks. According to a February 2011 statement by Google's Vint Cerf, the so-called "Bundle protocols" have been uploaded to NASA's EPOXI mission spacecraft (which is in orbit around the Sun) and communication with Earth has been tested at a distance of approximately 80 light seconds.[59]

Internet governance

As a globally distributed network of voluntarily interconnected autonomous networks, the Internet operates without a central governing body. It has no centralized governance for either technology or policies, and each constituent network chooses what technologies and protocols it will deploy from the voluntary technical standards that are developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).[60] However, throughout its entire history, the Internet system has had an "Internet Assigned Numbers Authority" (IANA) for the allocation and assignment of various technical identifiers needed for the operation of the Internet.[61] The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) provides oversight and coordination for two principal name spaces in the Internet, the Internet Protocol address space and the Domain Name System.

NIC, InterNIC, IANA and ICANN

The IANA function was originally performed by USC Information Sciences Institute, and it delegated portions of this responsibility with respect to numeric network and autonomous system identifiers to the Network Information Center (NIC) at Stanford Research Institute (SRI International) in Menlo Park, California. In addition to his role as the RFC Editor, Jon Postel worked as the manager of IANA until his death in 1998.

As the early ARPANET grew, hosts were referred to by names, and a HOSTS.TXT file would be distributed from SRI International to each host on the network. As the network grew, this became cumbersome. A technical solution came in the form of the Domain Name System, created by Paul Mockapetris. The Defense Data Network—Network Information Center (DDN-NIC) at SRI handled all registration services, including the top-level domains (TLDs) of .mil, .gov, .edu, .org, .net, .com and .us, root nameserver administration and Internet number assignments under a United States Department of Defense contract.[61] In 1991, the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) awarded the administration and maintenance of DDN-NIC (managed by SRI up until this point) to Government Systems, Inc., who subcontracted it to the small private-sector Network Solutions, Inc.[62][63]

The increasing cultural diversity of the Internet also posed administrative challenges for centralized management of the IP addresses. In October 1992, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) published RFC 1366,[64] which described the "growth of the Internet and its increasing globalization" and set out the basis for an evolution of the IP registry process, based on a regionally distributed registry model. This document stressed the need for a single Internet number registry to exist in each geographical region of the world (which would be of "continental dimensions"). Registries would be "unbiased and widely recognized by network providers and subscribers" within their region. The RIPE Network Coordination Centre (RIPE NCC) was established as the first RIR in May 1992. The second RIR, the Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC), was established in Tokyo in 1993, as a pilot project of the Asia Pacific Networking Group.[65]

Since at this point in history most of the growth on the Internet was coming from non-military sources, it was decided that the Department of Defense would no longer fund registration services outside of the .mil TLD. In 1993 the U.S. National Science Foundation, after a competitive bidding process in 1992, created the InterNIC to manage the allocations of addresses and management of the address databases, and awarded the contract to three organizations. Registration Services would be provided by Network Solutions; Directory and Database Services would be provided by AT&T; and Information Services would be provided by General Atomics.[66]

Over time, after consultation with the IANA, the IETF, RIPE NCC, APNIC, and the Federal Networking Council (FNC), the decision was made to separate the management of domain names from the management of IP numbers.[65] Following the examples of RIPE NCC and APNIC, it was recommended that management of IP address space then administered by the InterNIC should be under the control of those that use it, specifically the ISPs, end-user organizations, corporate entities, universities, and individuals. As a result, the American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN) was established as in December 1997, as an independent, not-for-profit corporation by direction of the National Science Foundation and became the third Regional Internet Registry.[67]

In 1998, both the IANA and remaining DNS-related InterNIC functions were reorganized under the control of ICANN, a California non-profit corporation contracted by the United States Department of Commerce to manage a number of Internet-related tasks. As these tasks involved technical coordination for two principal Internet name spaces (DNS names and IP addresses) created by the IETF, ICANN also signed a memorandum of understanding with the IAB to define the technical work to be carried out by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority.[68] The management of Internet address space remained with the regional Internet registries, which collectively were defined as a supporting organization within the ICANN structure.[69] ICANN provides central coordination for the DNS system, including policy coordination for the split registry / registrar system, with competition among registry service providers to serve each top-level-domain and multiple competing registrars offering DNS services to end-users.

Internet Engineering Task Force

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is the largest and most visible of several loosely related ad-hoc groups that provide technical direction for the Internet, including the Internet Architecture Board (IAB), the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG), and the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF).

The IETF is a loosely self-organized group of international volunteers who contribute to the engineering and evolution of Internet technologies. It is the principal body engaged in the development of new Internet standard specifications. Much of the IETF's work is done in Working Groups. It does not "run the Internet", despite what some people might mistakenly say. The IETF does make voluntary standards that are often adopted by Internet users, but it does not control, or even patrol, the Internet.[70][71]

The IETF started in January 1986 as a quarterly meeting of U.S. government-funded researchers. Non-government representatives were invited starting with the fourth IETF meeting in October 1986. The concept of Working Groups was introduced at the fifth IETF meeting in February 1987. The seventh IETF meeting in July 1987 was the first meeting with more than 100 attendees. In 1992, the Internet Society, a professional membership society, was formed and IETF began to operate under it as an independent international standards body. The first IETF meeting outside of the United States was held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, in July 1993. Today the IETF meets three times a year and attendnce is often about 1,300 people, but has been as high as 2,000 upon occasion. Typically one in three IETF meetings are held in Europe or Asia. The number of non-US attendees is roughly 50%, even at meetings held in the United States.[70]

The IETF is unusual in that it exists as a collection of happenings, but is not a corporation and has no board of directors, no members, and no dues. The closest thing there is to being an IETF member is being on the IETF or a Working Group mailing list. IETF volunteers come from all over the world and from many different parts of the Internet community. The IETF works closely with and under the supervision of the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG)[72] and the Internet Architecture Board (IAB).[73] The Internet Research Task Force (IRTF) and the Internet Research Steering Group (IRSG), peer activities to the IETF and IESG under the general supervision of the IAB, focus on longer term research issues.[70][74]

Request for Comments

Request for Comments (RFCs) are the main documentation for the work of the IAB, IESG, IETF, and IRTF. RFC 1, "Host Software", was written by Steve Crocker at UCLA in April 1969, well before the IETF was created. Originally they were technical memos documenting aspects of ARPANET development and were edited by Jon Postel, the first RFC Editor.[70][75]

RFCs cover a wide range of information from proposed standards, draft standards, full standards, best practices, experimental protocols, history, and other informational topics.[76] RFCs can be written by individuals or informal groups of individuals, but many are the product of a more formal Working Group. Drafts are submitted to the IESG either by individuals or by the Working Group Chair. An RFC Editor, appointed by the IAB, separate from IANA, and working in conjunction with the IESG, receives drafts from the IESG and edits, formats, and publishes them. Once an RFC is published, it is never revised. If the standard it describes changes or its information becomes obsolete, the revised standard or updated information will be re-published as a new RFC that "obsoletes" the original.[70][75]

The Internet Society

The Internet Society (ISOC) is an international, nonprofit organization founded during 1992 "to assure the open development, evolution and use of the Internet for the benefit of all people throughout the world". With offices near Washington, DC, USA, and in Geneva, Switzerland, ISOC has a membership base comprising more than 80 organizational and more than 50,000 individual members. Members also form "chapters" based on either common geographical location or special interests. There are currently more than 90 chapters around the world.[77]

ISOC provides financial and organizational support to and promotes the work of the standards settings bodies for which it is the organizational home: the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the Internet Architecture Board (IAB), the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG), and the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF). ISOC also promotes understanding and appreciation of the Internet model of open, transparent processes and consensus-based decision making.[78]

Globalization and Internet governance in the 21st century

Since the 1990s, the Internet's governance and organization has been of global importance to governments, commerce, civil society, and individuals. The organizations which held control of certain technical aspects of the Internet were the successors of the old ARPANET oversight and the current decision-makers in the day-to-day technical aspects of the network. While recognized as the administrators of certain aspects of the Internet, their roles and their decision making authority are limited and subject to increasing international scrutiny and increasing objections. These objections have led to the ICANN removing themselves from relationships with first the University of Southern California in 2000,[79] and finally in September 2009, gaining autonomy from the US government by the ending of its longstanding agreements, although some contractual obligations with the U.S. Department of Commerce continued.[80][81][82]

The IETF, with financial and organizational support from the Internet Society, continues to serve as the Internet's ad-hoc standards body and issues Request for Comments.

In November 2005, the World Summit on the Information Society, held in Tunis, called for an Internet Governance Forum (IGF) to be convened by United Nations Secretary General. The IGF opened an ongoing, non-binding conversation among stakeholders representing governments, the private sector, civil society, and the technical and academic communities about the future of Internet governance. The first IGF meeting was held in October/November 2006 with follow up meetings annually thereafter.[83] Since WSIS, the term "Internet governance" has been broadened beyond narrow technical concerns to include a wider range of Internet-related policy issues.[84][85]

Net neutrality

On April 23, 2014, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was reported to be considering a new rule that would permit Internet service providers to offer content providers a faster track to send content, thus reversing their earlier net neutrality position.[86][87][88] A possible solution to net neutrality concerns may be municipal broadband, according to Professor Susan Crawford, a legal and technology expert at Harvard Law School.[89] On May 15, 2014, the FCC decided to consider two options regarding Internet services: first, permit fast and slow broadband lanes, thereby compromising net neutrality; and second, reclassify broadband as a telecommunication service, thereby preserving net neutrality.[90][91] On November 10, 2014, President Obama recommended the FCC reclassify broadband Internet service as a telecommunications service in order to preserve net neutrality.[92][93][94] On January 16, 2015, Republicans presented legislation, in the form of a U.S. Congress H. R. discussion draft bill, that makes concessions to net neutrality but prohibits the FCC from accomplishing the goal or enacting any further regulation affecting Internet service providers (ISPs).[95][96] On January 31, 2015, AP News reported that the FCC will present the notion of applying ("with some caveats") Title II (common carrier) of the Communications Act of 1934 to the internet in a vote expected on February 26, 2015.[97][98][99][100][101] Adoption of this notion would reclassify internet service from one of information to one of telecommunications[102] and, according to Tom Wheeler, chairman of the FCC, ensure net neutrality.[103][104] The FCC is expected to enforce net neutrality in its vote, according to the New York Times.[105][106]

On February 26, 2015, the FCC ruled in favor of net neutrality by applying Title II (common carrier) of the Communications Act of 1934 and Section 706 of the Telecommunications act of 1996 to the Internet.[107][108][109] The FCC Chairman, Tom Wheeler, commented, "This is no more a plan to regulate the Internet than the First Amendment is a plan to regulate free speech. They both stand for the same concept."[110]

On March 12, 2015, the FCC released the specific details of the net neutrality rules.[111][112][113] On April 13, 2015, the FCC published the final rule on its new "Net Neutrality" regulations.[114][115]

Use and culture

Demographics

Email and Usenet

Email has often been called the killer application of the Internet. It predates the Internet and was a crucial tool in creating it. Email started in 1965 as a way for multiple users of a time-sharing mainframe computer to communicate. Although the history is undocumented, among the first systems to have such a facility were the System Development Corporation (SDC) Q32 and the Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) at MIT.[118]

The ARPANET computer network made a large contribution to the evolution of electronic mail. An experimental inter-system transferred mail on the ARPANET shortly after its creation.[119] In 1971 Ray Tomlinson created what was to become the standard Internet electronic mail addressing format, using the @ sign to separate mailbox names from host names.[120]

A number of protocols were developed to deliver messages among groups of time-sharing computers over alternative transmission systems, such as UUCP and IBM's VNET email system. Email could be passed this way between a number of networks, including ARPANET, BITNET and NSFNET, as well as to hosts connected directly to other sites via UUCP. See the history of SMTP protocol.

In addition, UUCP allowed the publication of text files that could be read by many others. The News software developed by Steve Daniel and Tom Truscott in 1979 was used to distribute news and bulletin board-like messages. This quickly grew into discussion groups, known as newsgroups, on a wide range of topics. On ARPANET and NSFNET similar discussion groups would form via mailing lists, discussing both technical issues and more culturally focused topics (such as science fiction, discussed on the sflovers mailing list).

During the early years of the Internet, email and similar mechanisms were also fundamental to allow people to access resources that were not available due to the absence of online connectivity. UUCP was often used to distribute files using the 'alt.binary' groups. Also, FTP e-mail gateways allowed people that lived outside the US and Europe to download files using ftp commands written inside email messages. The file was encoded, broken in pieces and sent by email; the receiver had to reassemble and decode it later, and it was the only way for people living overseas to download items such as the earlier Linux versions using the slow dial-up connections available at the time. After the popularization of the Web and the HTTP protocol such tools were slowly abandoned.

From Gopher to the WWW

As the Internet grew through the 1980s and early 1990s, many people realized the increasing need to be able to find and organize files and information. Projects such as Archie, Gopher, WAIS, and the FTP Archive list attempted to create ways to organize distributed data. In the early 1990s, Gopher, invented by Mark P. McCahill offered a viable alternative to the World Wide Web. However, in 1993 the World Wide Web saw many advances to indexing and ease of access through search engines, which often neglected Gopher and Gopherspace. As popularity increased through ease of use, investment incentives also grew until in the middle of 1994 the WWW's popularity gained the upper hand. Then it became clear that Gopher and the other projects were doomed fall short.[121]

One of the most promising user interface paradigms during this period was hypertext. The technology had been inspired by Vannevar Bush's "Memex"[122] and developed through Ted Nelson's research on Project Xanadu and Douglas Engelbart's research on NLS.[123] Many small self-contained hypertext systems had been created before, such as Apple Computer's HyperCard (1987). Gopher became the first commonly used hypertext interface to the Internet. While Gopher menu items were examples of hypertext, they were not commonly perceived in that way.

In 1989, while working at CERN, Tim Berners-Lee invented a network-based implementation of the hypertext concept. By releasing his invention to public use, he ensured the technology would become widespread.[124] For his work in developing the World Wide Web, Berners-Lee received the Millennium technology prize in 2004.[125] One early popular web browser, modeled after HyperCard, was ViolaWWW.

A turning point for the World Wide Web began with the introduction[126] of the Mosaic web browser[127] in 1993, a graphical browser developed by a team at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (NCSA-UIUC), led by Marc Andreessen. Funding for Mosaic came from the High-Performance Computing and Communications Initiative, a funding program initiated by the High Performance Computing and Communication Act of 1991 also known as the Gore Bill.[128] Mosaic's graphical interface soon became more popular than Gopher, which at the time was primarily text-based, and the WWW became the preferred interface for accessing the Internet. (Gore's reference to his role in "creating the Internet", however, was ridiculed in his presidential election campaign. See the full article Al Gore and information technology).

Mosaic was superseded in 1994 by Andreessen's Netscape Navigator, which replaced Mosaic as the world's most popular browser. While it held this title for some time, eventually competition from Internet Explorer and a variety of other browsers almost completely displaced it. Another important event held on January 11, 1994, was The Superhighway Summit at UCLA's Royce Hall. This was the "first public conference bringing together all of the major industry, government and academic leaders in the field [and] also began the national dialogue about the Information Superhighway and its implications."[129]

24 Hours in Cyberspace, "the largest one-day online event" (February 8, 1996) up to that date, took place on the then-active website, cyber24.com.[130][131] It was headed by photographer Rick Smolan.[132] A photographic exhibition was unveiled at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History on January 23, 1997, featuring 70 photos from the project.[133]

Search engines

Even before the World Wide Web, there were search engines that attempted to organize the Internet. The first of these was the Archie search engine from McGill University in 1990, followed in 1991 by WAIS and Gopher. All three of those systems predated the invention of the World Wide Web but all continued to index the Web and the rest of the Internet for several years after the Web appeared. There are still Gopher servers as of 2006, although there are a great many more web servers.

As the Web grew, search engines and Web directories were created to track pages on the Web and allow people to find things. The first full-text Web search engine was WebCrawler in 1994. Before WebCrawler, only Web page titles were searched. Another early search engine, Lycos, was created in 1993 as a university project, and was the first to achieve commercial success. During the late 1990s, both Web directories and Web search engines were popular—Yahoo! (founded 1994) and Altavista (founded 1995) were the respective industry leaders. By August 2001, the directory model had begun to give way to search engines, tracking the rise of Google (founded 1998), which had developed new approaches to relevancy ranking. Directory features, while still commonly available, became after-thoughts to search engines.

Database size, which had been a significant marketing feature through the early 2000s, was similarly displaced by emphasis on relevancy ranking, the methods by which search engines attempt to sort the best results first. Relevancy ranking first became a major issue circa 1996, when it became apparent that it was impractical to review full lists of results. Consequently, algorithms for relevancy ranking have continuously improved. Google's PageRank method for ordering the results has received the most press, but all major search engines continually refine their ranking methodologies with a view toward improving the ordering of results. As of 2006, search engine rankings are more important than ever, so much so that an industry has developed ("search engine optimizers", or "SEO") to help web-developers improve their search ranking, and an entire body of case law has developed around matters that affect search engine rankings, such as use of trademarks in metatags. The sale of search rankings by some search engines has also created controversy among librarians and consumer advocates.[134]

On June 3, 2009, Microsoft launched its new search engine, Bing.[135] The following month Microsoft and Yahoo! announced a deal in which Bing would power Yahoo! Search.[136]

File sharing

Resource or file sharing has been an important activity on computer networks from well before the Internet was established and was supported in a variety of ways including bulletin board systems (1978), Usenet (1980), Kermit (1981), and many others. The File Transfer Protocol (FTP) for use on the Internet was standardized in 1985 and is still in use today.[137] A variety of tools were developed to aid the use of FTP by helping users discover files they might want to transfer, including the Wide Area Information Server (WAIS) in 1991, Gopher in 1991, Archie in 1991, Veronica in 1992, Jughead in 1993, Internet Relay Chat (IRC) in 1988, and eventually the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1991 with Web directories and Web search engines.

In 1999, Napster became the first peer-to-peer file sharing system.[138] Napster used a central server for indexing and peer discovery, but the storage and transfer of files was decentralized. A variety of peer-to-peer file sharing programs and services with different levels of decentralization and anonymity followed, including: Gnutella, eDonkey2000, and Freenet in 2000, FastTrack, Kazaa, Limewire, and BitTorrent in 2001, and Poisoned in 2003.[139]

All of these tools are general purpose and can be used to share a wide variety of content, but sharing of music files, software, and later movies and videos are major uses.[140] And while some of this sharing is legal, large portions are not. Lawsuits and other legal actions caused Napster in 2001, eDonkey2000 in 2005, Kazza in 2006, and Limewire in 2010 to shutdown or refocus their efforts.[141][142] The Pirate Bay, founded in Sweden in 2003, continues despite a trial and appeal in 2009 and 2010 that resulted in jail terms and large fines for several of its founders.[143] File sharing remains contentious and controversial with charges of theft of intellectual property on the one hand and charges of censorship on the other.[144][145]

Dot-com bubble

Suddenly the low price of reaching millions worldwide, and the possibility of selling to or hearing from those people at the same moment when they were reached, promised to overturn established business dogma in advertising, mail-order sales, customer relationship management, and many more areas. The web was a new killer app—it could bring together unrelated buyers and sellers in seamless and low-cost ways. Entrepreneurs around the world developed new business models, and ran to their nearest venture capitalist. While some of the new entrepreneurs had experience in business and economics, the majority were simply people with ideas, and did not manage the capital influx prudently. Additionally, many dot-com business plans were predicated on the assumption that by using the Internet, they would bypass the distribution channels of existing businesses and therefore not have to compete with them; when the established businesses with strong existing brands developed their own Internet presence, these hopes were shattered, and the newcomers were left attempting to break into markets dominated by larger, more established businesses. Many did not have the ability to do so.

The dot-com bubble burst in March 2000, with the technology heavy NASDAQ Composite index peaking at 5,048.62 on March 10[146] (5,132.52 intraday), more than double its value just a year before. By 2001, the bubble's deflation was running full speed. A majority of the dot-coms had ceased trading, after having burnt through their venture capital and IPO capital, often without ever making a profit. But despite this, the Internet continues to grow, driven by commerce, ever greater amounts of online information and knowledge and social networking.

Mobile phones and the Internet

The first mobile phone with Internet connectivity was the Nokia 9000 Communicator, launched in Finland in 1996. The viability of Internet services access on mobile phones was limited until prices came down from that model and network providers started to develop systems and services conveniently accessible on phones. NTT DoCoMo in Japan launched the first mobile Internet service, i-mode, in 1999 and this is considered the birth of the mobile phone Internet services. In 2001, the mobile phone email system by Research in Motion for their BlackBerry product was launched in America. To make efficient use of the small screen and tiny keypad and one-handed operation typical of mobile phones, a specific document and networking model was created for mobile devices, the Wireless Application Protocol (WAP). Most mobile device Internet services operate using WAP. The growth of mobile phone services was initially a primarily Asian phenomenon with Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all soon finding the majority of their Internet users accessing resources by phone rather than by PC. Developing countries followed, with India, South Africa, Kenya, Philippines, and Pakistan all reporting that the majority of their domestic users accessed the Internet from a mobile phone rather than a PC. The European and North American use of the Internet was influenced by a large installed base of personal computers, and the growth of mobile phone Internet access was more gradual, but had reached national penetration levels of 20–30% in most Western countries.[147] The cross-over occurred in 2008, when more Internet access devices were mobile phones than personal computers. In many parts of the developing world, the ratio is as much as 10 mobile phone users to one PC user.[148]

Historiography

Some concerns have been raised over the historiography of the Internet's development. The process of digitization represents a twofold challenge both for historiography in general and, in particular, for historical communication research.[149] Specifically that it is hard to find documentation of much of the Internet's development, for several reasons, including a lack of centralized documentation for much of the early developments that led to the Internet.

"The Arpanet period is somewhat well documented because the corporation in charge – BBN – left a physical record. Moving into the NSFNET era, it became an extraordinarily decentralized process. The record exists in people's basements, in closets. [...] So much of what happened was done verbally and on the basis of individual trust."—Doug Gale (2007)[150]

See also

References

- ↑ Couldry, Nick (2012). Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice. London: Polity Press. p. 2.

- ↑ "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information", Martin Hilbert and Priscila López (2011), Science (journal), 332(6025), 60–65; free access to the article through here: martinhilbert.net/WorldInfoCapacity.html

- ↑ J. C. R. Licklider (March 1960). "Man-Computer Symbiosis". IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics. HFE-1: 4–11.

- ↑ J. C. R. Licklider and Welden Clark (August 1962). "On-Line Man-Computer Communication" (PDF). AIEE-IRE '62 (Spring): 113–128.

- ↑ Licklider, J. C. R. (23 April 1963). "Topics for Discussion at the Forthcoming Meeting, Memorandum For: Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network". Washington, D.C.: Advanced Research Projects Agency. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ Robert Taylor in an interview with John Markoff (December 20, 1999). "An Internet Pioneer Ponders the Next Revolution". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2005.

- ↑ "J.C.R. Licklider and the Universal Network". The Internet. 2000.

- ↑ Leonard Kleinrock (2005). "The history of the Internet". Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ Baran, Paul (May 27, 1960). "Reliable Digital Communications Using Unreliable Network Repeater Nodes" (PDF). The RAND Corporation. p. 1. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ Ruthfield, Scott (September 1995). "The Internet's History and Development From Wartime Tool to the Fish-Cam". Crossroads 2 (1). pp. 2–4. doi:10.1145/332198.332202. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ "About Rand". Paul Baran and the Origins of the Internet. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ Strickland, Jonathan (n.d.). "How ARPANET Works".

- ↑ Gromov, Gregory (1995). "Roads and Crossroads of Internet History".

- ↑ Hafner, Katie (1998). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83267-4.

- ↑ Ronda Hauben (2001). "From the ARPANET to the Internet". Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ Postel, J. (November 1981). "The General Plan". NCP/TCP transition plan. IETF. p. 2. RFC 801. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc801#page-2. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ↑ "NORSAR and the Internet". NORSAR. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ↑ Ward, Mark (October 29, 2009). "Celebrating 40 years of the net". BBC News.

- ↑ The Merit Network, Inc. is an independent non-profit 501(c)(3) corporation governed by Michigan's public universities. Merit receives administrative services under an agreement with the University of Michigan.

- ↑ A Chronicle of Merit's Early History, John Mulcahy, 1989, Merit Network, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Merit Network Timeline: 1970–1979, Merit Network, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- ↑ Merit Network Timeline: 1980–1989, Merit Network, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- ↑ "A Technical History of CYCLADES". Technical Histories of the Internet & other Network Protocols. Computer Science Department, University of Texas Austin.

- ↑ "The Cyclades Experience: Results and Impacts", Zimmermann, H., Proc. IFIP'77 Congress, Toronto, August 1977, pp. 465–469

- ↑ tsbedh. "History of X.25, CCITT Plenary Assemblies and Book Colors". Itu.int. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Events in British Telecomms History". Events in British TelecommsHistory. Archived from the original on April 5, 2003. Retrieved November 25, 2005.

- ↑ UUCP Internals Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ Barry M. Leiner, Vinton G. Cerf, David D. Clark, Robert E. Kahn, Leonard Kleinrock, Daniel C. Lynch, Jon Postel, Larry G. Roberts, Stephen Wolff (2003). "A Brief History of Internet". Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Computer History Museum and Web History Center Celebrate 30th Anniversary of Internet Milestone". Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ogg, Erica (2007-11-08). "'Internet van' helped drive evolution of the Web". CNET. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ↑ Jon Postel, NCP/TCP Transition Plan, RFC 801

- ↑ David Roessner, Barry Bozeman, Irwin Feller, Christopher Hill, Nils Newman (1997). "The Role of NSF's Support of Engineering in Enabling Technological Innovation". Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ "RFC 675 – Specification of internet transmission control program". Tools.ietf.org. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1996). Computer Networks. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-394248-1.

- ↑ Hauben, Ronda (2004). "The Internet: On its International Origins and Collaborative Vision". Amateur Computerist 12 (2). Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Internet Access Provider Lists". Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- ↑ "RFC 1871 – CIDR and Classful Routing". Tools.ietf.org. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ Ben Segal (1995). "A Short History of Internet Protocols at CERN".

- ↑ "Internet History in Asia". 16th APAN Meetings/Advanced Network Conference in Busan. Retrieved December 25, 2005.

- ↑ "Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000-2012", International Telecommunications Union (Geneva), June 2013, retrieved 22 June 2013

- ↑ "Fixed (wired)-broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants 2012", Dynamic Report, ITU ITC EYE, International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved on 29 June 2013.

- ↑ "Active mobile-broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants 2012", Dynamic Report, ITU ITC EYE, International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved on 29 June 2013.

- ↑ "ICONS webpage". Icons.afrinic.net. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ Nepad, Eassy partnership ends in divorce,(South African) Financial Times FMTech, 2007

- ↑ "APRICOT webpage". Apricot.net. May 4, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ "A brief history of the Internet in China". China celebrates 10 years of being connected to the Internet. Retrieved December 25, 2005.

- ↑ "Internet host count history". Internet Systems Consortium. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ↑ "The World internet provider". Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ OGC-00-33R Department of Commerce: Relationship with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (PDF). Government Accountability Office. July 7, 2000. p. 6.

- ↑ Even after the appropriations act was amended in 1992 to give NSF more flexibility with regard to commercial traffic, NSF never felt that it could entirely do away with its Acceptable Use Policy and its restrictions on commercial traffic, see the response to Recommendation 5 in NSF's response to the Inspector General's review (a April 19, 1993 memo from Frederick Bernthal, Acting Director, to Linda Sundro, Inspector General, that is included at the end of Review of NSFNET, Office of the Inspector General, National Science Foundation, March 23, 1993)

- ↑ Management of NSFNET, a transcript of the March 12, 1992 hearing before the Subcommittee on Science of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Second Congress, Second Session, Hon. Rick Boucher, subcommittee chairman, presiding

- ↑ "Retiring the NSFNET Backbone Service: Chronicling the End of an Era", Susan R. Harris, Ph.D., and Elise Gerich, ConneXions, Vol. 10, No. 4, April 1996

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Internet".

- ↑ NSF Solicitation 93-52 – Network Access Point Manager, Routing Arbiter, Regional Network Providers, and Very High Speed Backbone Network Services Provider for NSFNET and the NREN(SM) Program, May 6, 1993

- ↑ "Twitter post". 2010-01-22. Archived from the original on 2013-03-10. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- ↑ NASA Extends the World Wide Web Out Into Space. NASA media advisory M10-012, January 22, 2010. Archived

- ↑ NASA Successfully Tests First Deep Space Internet. NASA media release 08-298, November 18, 2008 Archived

- ↑ Disruption Tolerant Networking for Space Operations (DTN). July 31, 2012

- ↑ "Cerf: 2011 will be proving point for 'InterPlanetary Internet'". Network World interview with Vint Cerf. February 18, 2011. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Internet Architecture". IAB Architectural Principles of the Internet. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "DDN NIC". IAB Recommended Policy on Distributing Internet Identifier Assignment. Retrieved December 26, 2005.

- ↑ "GSI-Network Solutions". TRANSITION OF NIC SERVICES. Retrieved December 26, 2005.

- ↑ "Thomas v. NSI, Civ. No. 97-2412 (TFH), Sec. I.A. (DCDC April 6, 1998)". Lw.bna.com. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ "RFC 1366". Guidelines for Management of IP Address Space. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Development of the Regional Internet Registry System". Cisco. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ↑ "NIS Manager Award Announced". NSF Network information services awards. Retrieved December 25, 2005.

- ↑ "Internet Moves Toward Privatization". http://www.nsf.gov''. 24 June 1997.

- ↑ "RFC 2860". Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Technical Work of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. Retrieved December 26, 2005.

- ↑ "ICANN Bylaws". Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 70.4 "The Tao of IETF: A Novice's Guide to the Internet Engineering Task Force", FYI 17 and RFC 4677, P. Hoffman and S. Harris, Internet Society, September 2006

- ↑ "A Mission Statement for the IETF", H. Alvestrand, Internet Society, BCP 95 and RFC 3935, October 2004

- ↑ "An IESG charter", H. Alvestrand, RFC 3710, Internet Society, February 2004

- ↑ "Charter of the Internet Architecture Board (IAB)", B. Carpenter, BCP 39 and RFC 2850, Internet Society, May 2000

- ↑ "IAB Thoughts on the Role of the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF)", S. Floyd, V. Paxson, A. Falk (eds), RFC 4440, Internet Society, March 2006

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "The RFC Series and RFC Editor", L. Daigle, RFC 4844, Internet Society, July 2007

- ↑ "Not All RFCs are Standards", C. Huitema, J. Postel, S. Crocker, RFC 1796, Internet Society, April 1995

- ↑ Internet Society (ISOC) – Introduction to ISOC

- ↑ Internet Society (ISOC) – ISOC's Standards Activities

- ↑ USC/ICANN Transition Agreement

- ↑ ICANN cuts cord to US government, gets broader oversight: ICANN, which oversees the Internet's domain name system, is a private nonprofit that reports to the US Department of Commerce. Under a new agreement, that relationship will change, and ICANN's accountability goes global Nate Anderson, September 30, 2009

- ↑ Rhoads, Christopher (October 2, 2009). "U.S. Eases Grip Over Web Body: Move Addresses Criticisms as Internet Usage Becomes More Global". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Rabkin, Jeremy; Eisenach, Jeffrey (October 2, 2009). "The U.S. Abandons the Internet: Multilateral governance of the domain name system risks censorship and repression". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Mueller, Milton L. (2010). Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance. MIT Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-262-01459-5.

- ↑ Mueller, Milton L. (2010). Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance. MIT Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-262-01459-5.

- ↑ DeNardis, Laura, The Emerging Field of Internet Governance (September 17, 2010). Yale Information Society Project Working Paper Series.

- ↑ Wyatt, Edward (April 23, 2014). "F.C.C., in ‘Net Neutrality’ Turnaround, Plans to Allow Fast Lane". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ Staff (April 24, 2014). "Creating a Two-Speed Internet". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ Carr, David (May 11, 2014). "Warnings Along F.C.C.’s Fast Lane". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ Crawford, Susan (April 28, 2014). "The Wire Next Time". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ↑ Staff (May 15, 2014). "Searching for Fairness on the Internet". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ↑ Wyatt, Edward (May 15, 2014). "F.C.C. Backs Opening Net Rules for Debate". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ↑ Wyatt, Edward (November 10, 2014). "Obama Asks F.C.C. to Adopt Tough Net Neutrality Rules". New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ↑ NYT Editorial Board (November 14, 2014). "Why the F.C.C. Should Heed President Obama on Internet Regulation". New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ↑ Sepulveda, Ambassador Daniel A. (January 21, 2015). "The World Is Watching Our Net Neutrality Debate, So Let’s Get It Right". Wired (website). Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ↑ Weisman, Jonathan (January 19, 2015). "Shifting Politics of Net Neutrality Debate Ahead of F.C.C. Vote". New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ↑ Staff (January 16, 2015). "H. R. _ 114th Congress, 1st Session [Discussion Draft] - To amend the Communications Act of 1934 to ensure Internet openness..." (PDF). U. S. Congress. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ↑ Lohr, Steve (February 2, 2015). "In Net Neutrality Push, F.C.C. Is Expected to Propose Regulating Internet Service as a Utility". New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Lohr, Steve (February 2, 2015). "F.C.C. Chief Wants to Override State Laws Curbing Community Net Services". New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Flaherty, Anne (January 31, 2015). "Just whose Internet is it? New federal rules may answer that". AP News. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ↑ Fung, Brian (January 2, 2015). "Get ready: The FCC says it will vote on net neutrality in February". Washington Post. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Staff (January 2, 2015). "FCC to vote next month on net neutrality rules". AP News. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Lohr, Steve (February 4, 2015). "F.C.C. Plans Strong Hand to Regulate the Internet". New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ Wheeler, Tom (February 4, 2015). "FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler: This Is How We Will Ensure Net Neutrality". Wired (magazine). Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ The Editorial Board (February 6, 2015). "Courage and Good Sense at the F.C.C. - Net Neutrality's Wise New Rules". New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2015.