History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit

Bay Area Rapid Transit, widely known by the acronym BART, is the main rail transportation system for the San Francisco Bay Area. It was envisioned as early as 1946 but the construction of the original system began in the 1960s.

Origins and planning

The idea of an underwater electric rail tube was first proposed in the early 1900s by Francis "Borax" Smith. It is no coincidence that much of BART's current coverage area was once served by the electrified streetcar and suburban train network called the Key System. This early twentieth century system once had regular trans-bay traffic across the lower deck of the Bay Bridge. By the 1950s the entire system had been dismantled in favor of automobiles and buses and the explosive growth of highway construction.

There were also plans for a third-rail powered subway line (Twin Peaks Tunnel) under Market Street in the 1910s.[1]

Proposals for the modern rapid transit system now in service began in 1946 by Bay Area business leaders concerned with increased post-war migration and growing congestion in the region. An Army-Navy task force concluded that an additional trans-bay crossing would soon be needed and recommended a tunnel; however, actual planning for a rapid transit system did not begin until the 1950s. In 1951, California's legislature created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission to study the Bay Area's long-term transportation needs. The commission's 1957 final report concluded the most cost-effective solution for the Bay Area's traffic woes would be to form a transit district charged with the construction and operation of a high-speed rapid rail system linking the cities and suburbs. Nine Bay Area counties were included in the initial planning commission.[2]

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District was formed by the state legislature in 1957, comprising the counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo. Because Santa Clara County opted instead to first concentrate on its Expressway System, that county was not included in the original BART District.

In 1959 a bill was passed in the state legislature that provided for the entire cost of construction of the tube to be paid for with surplus toll revenues from the San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge. This represented a significant portion of the total cost of the system.[3]

By 1961 a final plan for the new system was sent to the boards of supervisors of each of the five counties. The system's initial plans were for four lines connecting Concord in the east, Richmond in the northeast, Fremont in the southeast, Palo Alto in the southwest, and Novato in the north-west. However, in April 1962 San Mateo County made the decision to opt out, citing high costs, existing service provided by Southern Pacific commuter trains, and concerns over shoppers leaving their county for stores in San Francisco. Marin County followed soon thereafter in May. Marin was forced out of the BART district because of engineering objections from the board of directors of the Golden Gate Bridge. BART officials refused to allow Marin supervisors to stay in the district because they were afraid Marin voters would not approve the bonds, which had to win more than 60% approval.[4] The BART plans were finally approved by the voters of the three remaining participating counties in November 1962.

In the 1980s planning was underway for extension south from San Francisco, the first step being the Daly City Tailtrack Project, upon which turnaround project the San Francisco Airport Extension would later build.[5]

BART has been featured in a number of films including:[6] the unfinished Transbay Tube in THX 1138; The Domino Principle, wherein Gene Hackman's character is on a train at the Fruitvale station; a fight scene in Predator 2; and The Pursuit of Happyness, which showed numerous BART stations including a fictional one in Duboce Park that prompted complaints that the new station only had one entrance, this entrance was in reality a set design for the film. The system has also been showed in other films but has played a less significant role such as being in the background as in The Kite Runner, They Call Me Mister Tibbs!, An Eye for an Eye, and Kuffs. Mission District stations were also used in at least one episode of The Streets of San Francisco. In addition to feature films there is an "underground earthquake simulator" at Universal Studios Hollywood that uses a BART train.[6]

Construction of the initial system

BART construction officially began on June 19, 1964 with President Lyndon Johnson presiding over the ground-breaking ceremonies at the 4.4-mile (7.1 km) test track between Concord and Walnut Creek in Contra Costa County.

The enormous tasks to be undertaken were daunting. System wide projects would include the construction of three underground rail stations in Oakland's populated downtown area, four stations through San Francisco’s downtown beneath Market Street, as well as four other underground stations in other parts of San Francisco, three subterranean stations in Berkeley (which paid more to bury them, in contrast to the stations in neighboring Oakland and El Cerrito), the 3.5 mile (5.6 km) tunnel through the Berkeley Hills; and of course the 3.6 mile (5.8 km) Transbay Tube between Oakland and San Francisco beneath the San Francisco Bay. Constructed in 57 sections, The Tube is the world's longest and deepest immersed tunnel at cost $180 million and was completed in August 1969.

BART's initial cost was $1.6 billion, which included both the initial system and the Transbay Tube. Adjusted for inflation, this cost would be valued at $15 billion in 2004.

Operation

BART began service on September 11, 1972, reporting more than 100,000 passengers in its first five days. The Market Street Subway opened in 1973[7] and the Transbay Tube finally opened on September 16, 1974, linking the four branches to Daly City, Concord, Richmond, and Fremont. Service then was still 14 hours a day, and for five years BART operated weekday-only: Saturday trains began November 1977 and Sunday in July 1978. Fare in 1972-74 was $1.20 from Concord or $1.25 from Fremont to any station west of the bay; Richmond to Fremont was $1.10.

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake severed the San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge for a month and destroyed the Cypress Street Viaduct. With some Bay Area freeways damaged or destroyed, BART trains, within six hours of the earthquake, were again running. Even with service interruptions following aftershocks for inspection of tracks, over- and under-crossings, and tunnels, BART continued to run.

Expansion was made possible by an agreement under which San Mateo County was to contribute $200 million to East Bay extensions as a “buy-in” to the system without actually joining the BART district. Trains to North Concord/Martinez began on December 16, 1995 and to Pittsburg/Bay Point on December 7, 1996. Service south of Daly City began on February 24, 1996, to Colma. On May 10, 1997 service began from Bay Fair to Castro Valley and Dublin/Pleasanton.[8] The Dublin/Pleasanton extension now has transbay trains, but it was planned to have just shuttle trains between Dublin/Pleasanton and Bay Fair.[9]

Labor

BART workers are currently organized in 4 unions: the Service Employees International Union Local 1021, Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1555, American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 3333, and the BART Police Officer's Association.

1976 strike

BART has a unionized work force that went on strike for two weeks in 1976 in solidarity with the BART Police Officers Association. During the 1970s BART union workers received quarterly cost of living increases.

1979 lockout/strike

In 1979 there was a 90 day lockout by management, or a strike by union workers, depending on who one believes. Trains ran during this period because one of the unions, AFSCME, was then only an informal association known as BARTSPA, and management and BARTSPA had enough staff to keep trains running. One result of this strike is that the cost-of-living increases were greatly reduced to an amount far below the Consumer Price Index, and such raises are only received if no other raise occurs in a particular year.

1997 strike

For six days in September 1997, a BART strike caused a system-wide shutdown. This resulted in a four-year contract offering a 7% raise, and a one-time payment of $3,000 to all employees in lieu of a raise the first year. Such one-time payments are becoming more common as a way to prevent the effects of compounding on wages and salaries.

In addition, BART began large scale layoffs of rank and file workers, increasing the workload on those remaining.

2001 negotiations

In its 2001 negotiations, the BART unions fought for, and won, a 24 percent wage increase over four years with continuing benefits for employees and retirees.[10]

2005 negotiations

Another threatened strike on July 6, 2005 was averted by a last-minute agreement between management and the unions. In this agreement, Union workers received a 7% raise over four years, and paid an increase in the cost of medical insurance. The net increase (3%) was well below inflation, which was about 10% cumulative (about 2.4% per year) over the period of the contract. [11] The net increase was also below the average private sector raise, which was 4.6% for 2006.

2009 negotiations

The outcome of the 2009 contract negotiations were a four-year wage freeze, reduced pensions, and changes to work rules.[12] These new terms provided a $100 million savings to BART from 2009 to 2013.[13]

2013 strikes

BART employees went on strike on July 1, 2013, over pay and safety issues. The strike was ended July 5, when both sides agreed to a 30-day cooling off period (which ended Monday, August 5).[14] A second strike began on Friday, October 18, 2013, over unresolved compensation and work rule issues. Management offered a 12% wage increase over 4 years, of which 4% would be taken back as an increase in the required pension contribution; 9.5% increase in healthcare premiums, and changes to work rules including fewer fixed work schedules. Unions were willing to accept the financial terms but requested binding arbitration for the work rules. Management refused the arbitration offer.[15]

Awards

In October 2004 BART received the American Public Transportation Association's Outstanding Public Transportation System Award for 2004 in the category of transit systems with 30 million or more annual passenger trips.[16] BART issued announcements and began a promotional campaign declaring that it had been named Number One Transit System in America.[17] In 2006 the same industry trade group presented BART with the token AdWheel award for 'creative approaches to marketing transit' in recognition for BART's development of an iPod-based trip planner.[18]

Incidents and accidents

There have been no accidents attributed to brake failure. The following incidents are known to have occurred on the BART system:

- In 1972, shortly after the system opened, a test train carrying no passengers, dubbed the Fremont Flyer, failed to stop at the end of the line at Fremont and ran into the parking lot. There were several injuries.[19]

- The Transbay Tube was closed from January 17 to April 4, 1979, after a train caught fire in the tube, injuring dozens, killing a fireman, and damaging equipment.[20] Most of the injuries were caused by inhalation of toxic smoke from the burning polyurethane in the seats, leading to a $118,000 replacement program which was completed in November 1980.[2]

- On December 17, 1992, a BART train derailed south of 12th Street station and caused a five-day closure of the line.[21]

- On March 9, 2006, debris on BART tracks between Montgomery and Embarcadero stations caught fire and caused a 1.5 hour system-wide shutdown. Frustrated passengers accused BART of mishandling the incident.[22]

- On March 28 and 29, 2006, BART experienced computer glitches in its system during rush hour, which left about 35,000 commuters stranded inside trains or stations while the problem was being resolved.

- On December 1, 2006, a BART train jumped the tracks near the Oakland Wye, between 12th Street and Lake Merritt stations. There were no injuries.[23]

- On May 10, 2008, two separate early morning fires at different power substations disrupted service on the Fremont line. No injuries were reported from the incident. The resulting damage left the Fremont line impaired as several computer control loops went offline between South Hayward and Union City Stations. Train operators were forced to manually drive trains at a reduced speed of 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). Normal service was finally restored on July 13, 2008, two weeks before initial estimates.

- On October 14, 2008, a BART track worker was killed by a train near the Concord-Walnut Creek border. The Pittsburg/Bay Point line was the most affected by the accident.

- On December 29, 2008, shortly after 7 PM, an electrical fire broke out near the Walnut Creek station. The fire apparently started after a train ripped off a portion of the electric third rail, dragging it under the train and sparking a fire along the rail. The fire caused major delays of 2–3 hours, as Pittsburg/Bay Point bound trains could travel no further than Lafayette station, and San Francisco Airport bound trains were held at Concord station, having to be taken out of service as the delays continued. A bus shuttle system was set up to take passengers along the Concord, Pleasant Hill, Walnut Creek, and Lafayette BART stations. Trains were eventually allowed through the station in both directions, sharing one track until the rail was repaired.

- On January 1, 2009, there was an officer-involved shooting at the Fruitvale station, killing one person. See BART Police shooting of Oscar Grant.

- On February 3, 2009, two trains collided at low speed while approaching the 12th Street station, injuring a dozen people.[24]

- On July 16, 2009 a westbound Dublin/Pleasanton train struck a construction worker at the upcoming West Dublin Station. None of the 75–100 passengers on the train were hurt. Service was affected for 30 minutes on both lanes and passengers were forced to stay on their trains until BART decided for the affected train to head back to the Dublin/Pleasanton Station where passengers could exit. Operations resumed a few hours later.[25]

- On December 9, 2009 a train derailed between Lake Merrit and 12th Street stations in Oakland, California.

- On Sunday, March 13, 2011 the eighth and ninth cars of a ten car train derailed after leaving the Concord station at slow speed. Three minor back injuries were reported.[26] The train carried about 65 people at that time.[27] After the derailment, buses were employed to shuttle the passengers between the BART stations of Pleasant Hill and Pittsburg/Bay Point.[26] The repairs lasted into the night and were completed before the Monday morning commute.[27] A similar event occurred at the same location on the evening of February 21, 2014 to a train not in passenger service,[26] and a similar bus bridge was employed among North Concord, Concord, and Pleasant Hill stations on February 22, 2014 while emergency repairs were made.

- On October 19, 2013 two BART workers were struck and killed while inspecting a track section between the Walnut Creek and Pleasant Hill stations. [28]

Lines

Current lines

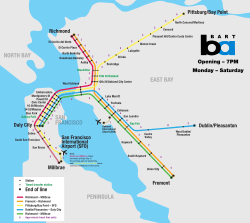

Trains regularly operate on five routes. Unlike most other rapid transit and rail systems around the world, BART lines are generally not referred to by shorthand designations. Although the lines have been colored consistently on BART system maps since inception, they are only occasionally referred to officially by color names.[29] However, future train cars will display line colors more prominently.[30]

BART announcements refer to by their destination(s) (e.g., “Richmond train” or “Richmond-bound train”). Electronic destination signs add “San Francisco” to the destination of any westbound transbay train or eastbound train west of San Francisco to make it clear that it will be passing through the city, and “SFO Airport” (or just “SFO”) is added to any train going to the airport. This can cause cumbersome descriptions, such as “San Francisco/Daly City train”, “San Francisco/SFO Airport/Millbrae train”, and “San Francisco/Pittsburg/Bay Point train.” On evenings and weekends, the longest name is “SFO Airport/San Francisco/Pittsburg/Bay Point," Only the first car of each train carries a destination sign, but all platforms have displays showing the destination of each train, with voice announcements.[31]

In many places in the BART system, multiple lines merge and share stations and tracks. Four lines share the Transbay Tube, all San Francisco stations, the Daly City Station and West Oakland Station. During peak hours multiple lines vie for track space. Only 4½ trains per hour per line (18 total trains per hour through the Tube) can be achieved after headways and dwell times are accounted for. The lack of passing tracks or sidings makes for challenging recoveries from traffic delays.

Defunct lines

In 1996, when the I-680/State Route 24 interchange in Walnut Creek was overhauled for construction, BART added temporary commuter train service during rush hours, which ran between South Hayward and Concord stations. The service ceased when the interchange was finished.

At the time when the BART-SFO Extension opened on June 22, 2003, there was a Millbrae–SFO Line, a shuttle line that operated every 20 minutes between Millbrae and San Francisco Airport, formerly depicted as a purple line. This line has been defunct as of February 2004. It was replaced by the Dublin/Pleasanton–Millbrae line that stopped at SFO Station on its way to Millbrae. On January 1, 2008, this service was completely eliminated; passengers traveling from points south to the airport have the inconvenience of boarding a train at Millbrae, travel to San Bruno, and then take a different train back to the airport, adding minutes to get to SFO. Direct service to SFO from Millbrae was finally restored in September 2009, but only Monday to Friday after 8 p.m. and all day Saturday and Sunday, via the off-peak Pittsburg/Bay Point–SFO/Millbrae line; during weekday peak hours SFO passengers from Millbrae still have to endure travel to and transfer at San Bruno station in order to reach SFO.

AirBART operated between the current Oakland Coliseum Station and the Oakland International Airport. The service was discontinued on November 22, 2014 with the opening of the Coliseum–Oakland International Airport line automated guideway transit system. AirBART was a joint project of BART and the Port of Oakland, which owns and operates the airport.[32] It was operated by Veolia Transportation under contract. As of December 2009, the AirBART fleet consisted of five Eldorado Axess buses running on compressed natural gas (CNG).[33]

Automation

BART was one of the first U.S. systems of any size to have substantial automated operations. The trains are computer-controlled via BART's Operations Control Center (OCC) and headquarters at Lake Merritt and generally arrive with regular punctuality. Train operators duties may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Monitors console and radio communications to ensure that vehicles are operating within established guidelines;

- Observes and detects problems with passengers entering and exiting train doors and takes corrective action; observes and detects hazards on the track, in the station or platforms, or the train itself, reports them to Operations Control Center personnel via radio, and take necessary corrective action;

- Make announcements to passengers regarding station arrivals, transfer points, delays, and emergencies and answers passenger questions;

- In yards, on test tracks, turntables and wash facilities, follows directions from Tower personnel and operates console to move trains as directed;

- Takes prescribed action such as evacuating passengers, administer first aid, and using a fire extinguisher during emergencies;

- Reports basic equipment malfunctions of mechanical or electrical nature to Operations Control Center; works with foreworkers and technicians to isolate reported problems;

- Maintains logs of work activities; completes forms to report unusual circumstances and action taken;

- Uses a variety of communication equipment, including a public address system, two‑way radios and emergency telephones;

- Monitors and learns to apply changes in operating and emergency procedures;

- Maintains and upgrades knowledge of policies and procedures as required.

As a first-generation system, BART's automation system was plagued with numerous operational problems during its first years of service. Shortly after revenue service began, an on-board electronics failure caused one two-car test train (with car 143 as the lead car) to run off the end of the elevated track at the Fremont station and into a parking lot. This incident was dubbed the Fremont Flyer, and there were no serious injuries.[19][34] When revenue service began, "ghost trains" (or false occupancies), trains that show up on the computer system as being in a specific place but don't physically exist, were common, and real trains could at times disappear from the system, as a result of dew on the tracks and too low of a voltage (at 0.6 volts rather than the industry standard 15 volts) being passed through the rails for train detection.[34] Under such circumstances, trains had to be operated manually and were restricted to a speed of 25 mph (40 km/h). Enhancements were made to the train control system to address these "ghost trains" (or false occupancies). However, manual blocking — operators in a booth on the platform at alternate stations, with a telephone and red/green lights — that kept trains in stations until the train ahead had left its station were mandated for several years.

The original signaling technology and subsequent enhancements used to control the trains was developed by Westinghouse.

During this initial shakedown period, there were several episodes where trains had to be manually run and signaled via station agents communicating by telephone. This caused a great outcry in the press and led to a flurry of litigation among Westinghouse, the original controls contractor, and BART, as well as public battles between the state government (advised by University of California professor Dr. Bill Wattenburg), the federal government, and the district, but in time these problems were resolved and BART became a reliable service.[34] Ghost trains apparently still persist on the system to this day and are usually cleared quickly enough to avoid significant delay, but occasionally some can cause an extended backup of manually operated trains in the system.[35] In addition, the fare card system was easily hackable with equipment commonly found in universities, although most of these flaws have been fixed.[36]

San Francisco International Airport extension

The $1.5 billion extension of BART southward to San Francisco International Airport's (SFO) Garage G, adjacent to the International Terminal, was opened to the public on June 22, 2003. Ground was broken on the project in November 1997, adding four new stations including the SFO station, South San Francisco, San Bruno, and Millbrae. The Millbrae station has a cross-platform connection to Caltrain, the first of its kind west of the Mississippi.[37] The airport extension used to run from SFO to Millbrae station, and operated with two train operators—one on each end of the train—between the San Bruno and Millbrae stations to reduce dwell time at SFO during peak hours; the train entered the SFO stub-end station under the control of the primary operator and exited in the opposite direction towards Millbrae controlled by the secondary. Since SFO is now the terminus of the line that serves it, this practice was discontinued as it would not reduce the in-transit time for any trips.

The airport extension project added 8.7 miles (14.0 km) of new railway; 6.1 miles (9.8 km) of subway, 1.2 miles (1.9 km) of aerial, and 1.4 miles (2.3 km) of at-grade track. The launch point was the Daly City Tailtrack project, which extended the tracks further south of the existing terminus in San Francisco and was completed in the 1980s.[38][39]

The project has not been without problems, however. The SFO extension currently draws 35,107 daily riders, significantly less than its target of 50,000 average weekday riders.[40] Another significant problem of note had been the rocky relationship between BART and San Mateo County Transit District (SamTrans) which was not a part of the BART district, but by agreement was responsible for the extension's operating costs. Fueled by the reality that the extension was not paying for itself, the acrimony between BART and SamTrans over changes and reductions in bus and train service reached a high.[41][42][43] BART wanted to increase service to attract ridership, while SamTrans wanted to reduce service to trim costs. Thus, service along the extension was changed several times.[44][45] Eventually SamTrans and BART worked out a deal in which SamTrans paid BART $32 million, plus approximately $2 million a year, and BART assumed all costs and control of operating the extension.

The latest revision to the SFO service has Pittsburg-Bay Point trains running to SFO at all times, with Dublin-Pleasanton trains terminating at Daly City. During peak times Mondays through Saturdays, Richmond trains will run to directly Millbrae without stopping at SFO. During off-peak hours (nights and weekends), Pittsburg-Bay Point trains will run to Millbrae (replacing Richmond service on the extension) through SFO. Consequently, the new routing requires passengers connecting between the Richmond, Dublin/Pleasanton, and Fremont lines and San Francisco International Airport to make an additional transfer. In addition, the cessation of direct BART service between Millbrae and SFO during weekday peak hours requires Caltrain passengers wanting to travel to the airport to make an additional transfer at San Bruno Station.

Many critics of the SFO Extension contend the project was merely a cover for BART's ultimate goal of ringing the bay, eliminating Caltrain altogether.[46]

The most use the new line has gotten on any single day was 37,200; the SFO Station receives an average of 10,700 passengers daily.[47]

Dates of openings

- September 11, 1972: MacArthur–Fremont (MacArthur, 19th St. Oakland, 12th St. Oakland City Center, Lake Merritt, Fruitvale, Coliseum/Oakland Airport, San Leandro, Bay Fair, Hayward, South Hayward, Union City, Fremont)

- January 29, 1973: MacArthur–Richmond (Ashby, Downtown Berkeley, North Berkeley, El Cerrito Plaza, El Cerrito del Norte, Richmond)

- May 21, 1973: MacArthur–Concord (Rockridge, Orinda, Lafayette, Walnut Creek, Pleasant Hill, Concord)

- November 5, 1973: Montgomery–Daly City (Montgomery St., Powell St., Civic Center/UN Plaza, 16th St. Mission, 24th St. Mission, Glen Park, Balboa Park, Daly City)

- September 16, 1974: Transbay Tube, West Oakland

- May 27, 1976: Embarcadero (infill station)

- December 16, 1995: North Concord/Martinez

- February 24, 1996: Colma

- December 7, 1996: Pittsburg/Bay Point

- May 10, 1997: Bay Fair–Dublin/Pleasanton (Castro Valley, Dublin/Pleasanton)

- June 22, 2003: Colma–SFO/Millbrae (South San Francisco, San Bruno, San Francisco International Airport, Millbrae)

- February 19, 2011: West Dublin/Pleasanton (infill station)

- November 22, 2014: Coliseum–Oakland International Airport (BART to Oakland International Airport)

- Planned 2015: Warm Springs/South Fremont

- Planned 2016: Warm Springs–Berryessa (Milpitas, Berryessa)

- Planned 2017: eBART (Antioch)

References

- ↑ McGraw Publishing: REPORT ON MARKET STREET RAPID TRANSIT TUNNEL. In: Electric Railway Journal, Vol. XL, No. 15, October 19, 1912, p. 883.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "History of BART (1946-1972)". BART. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ See BART Composite Report, prepared by Parsons Brinkerhof Tutor Bechtel, 1962

- ↑ "History of BART to the South Bay". the San Jose Mercury News. January 8, 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ C. M. Hogan, Kay Wilson, M. Papineau et al., Environmental Impact Statement for the BART Daly City Tailtrack Project, Earth Metrics, published by the U.S Urban Mass Transit Administration and the Bay Area Rapid Transit District 1984

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 BART in the movies: From THX 1138 to Predator 2 to Will Smith, BART News, August 8, 2008, accessed August 18, 2008

- ↑ A Full BART Chronology (269k .pdf)

- ↑ "The Story of LAVTA and Wheels". Archived from the original on 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2007-01-18."

- ↑ "Dublin Line: Castro Valley – Dublin". Transit-Rider.com. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Patrick Hoge (2005-07-03). "BART pay ranks high for transit workers". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ CoinNews (2013). "Current US Inflation Rates: 2003-2013". CoinNews. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ BART (2009). "AGREEMENT BETWEEN SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA RAPID TRANSIT DISTRICT AND BART SUPERVISORY AND PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATION (BARTSPA) AFSCME LOCAL 3993" (PDF). BART. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ↑ Zach Williams (August 27, 2009). "BART Talks Come to an End as Union Approves Contract". Daily Californian. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ↑ Micheline Maynard (July 5, 2013). "San Francisco BART Strike Ends, Ride-Sharing Raises Its Profile". Forbes. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ Laura Clawson (October 10, 2013). "San Francisco BART workers strike". Daily Kos. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ↑ Virginia Miller (October 10, 2004). "BART Receives National Recognition As APTA 2004 Outstanding Public Transportation System". American Public Transportation Association. Archived from the original on 2006-03-25. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ "BART Newsletter: BART named #1 Transit System in US". BART. August 24, 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ "Get BART schedules on your iPod". BART. December 4, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 BART: Bay Area Rapid Transit, world.nycsubway.org.

- ↑ "Reflections, the 1970s". the San Francisco Chronicle. December 26, 1999. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ↑ "BART Chronology January 1947 – June 2005" (PDF). BART. 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Ramas, George L.; Tom Busse (2006-03-14). "Letters to the Editor: BART mishandled SF subway track fire". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Hoffman, Ian (2006-12-02). "Car derailment stalls BART for hours". Oakland Tribune.

- ↑ "13 Passengers Sustain Minor Injuries In BART Collision". KTVU. 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ "East Bay News: Construction Worker Struck by BART Train". KGO-TV 7. 2009-07-16. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "BART train derails in Northern California; 3 injured". LA Times. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "East Bay BART service crippled following derailment". SF Examiner. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ http://www.mercurynews.com/breaking-news/ci_24347326/two-bart-workers-killed-during-maintenance-work-strike

- ↑ "BART to run on Sunday schedule Christmas Day". BART. December 21, 2006. Archived from the original on January 21, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ↑ "New Train Car Project". Bart.gov. 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ↑ BART - Disabled Access, Overview

- ↑ "AirBART fares going up". San Francisco Business Times. February 21, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.flyoakland.com/noise/environmental_airquality.shtml

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Bill Wattenburg (October 11, 2004). "BART—Bay Area Rapid Transit System (1972–74)". PushBack.com. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Bay City News (February 16, 2005). "'Ghost Train,' Malfunctions Causing BART Delays". FOXReno.com. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Peter Sheerin (October 11, 2004). "Magnetic Credit Cards". PushBack.com. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ "About the San Mateo County Transit District". SamTrans. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Michael Cabanatuan (April 18, 2003). "BART to link to SFO June 22 After many delays, latest date is firm, transit officials say". the San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ "Transportation Alternatives for the Bay Area, "Nothing but the Facts"" (PDF). Samceda Peninsula Policy Partnership. April 12, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-21. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Denis Cuff (April 23, 2008). "Ridership soars on BART line to SFO". Contra Costa Times. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ Erik Nelson (May 14, 2006). "BART to SFO falls short of success story". San Mateo County Times. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Tom Dempsey (May 31, 2005). "San Mateo County BART disaster: We told you so, in 1995". San Mateo County Times. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Edward Carpenter (July 27, 2006). "SamTrans struggles with fiscal woes". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Michael Cabanatuan (August 12, 2005). "BART's directors approve plan to trim service to S.F. airport". the San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ "Bay Area Rapid Transit's past, present, and possible futures". San Francisco Cityscape. Archived from the original on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Alan Hirsch (April 20, 1996). "FAQ 13 BART Around the Bay rev 0.31". Google Groups: ba.transportation. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ BART to SFO ridership jumps 65%, BART News, June 26, 2008, access date August 26, 2008