History of the African Americans in Los Angeles

| Part of a series on |

| Ethnicity in Los Angeles |

|---|

This article discusses the African-American community in Los Angeles.

History

When Los Angeles was first established in 1781, 26 of the 46 original settlers were black or mulatto, meaning a mixture of African and Spanish origins.

Beginning in 1793, Juan Francisco Reyes, a mulatto settler, served as elected mayor of Los Angeles. A member of the 1769 Portola expedition, Reyes would serve three terms as mayor.

Pío Pico, California's last governor under Mexican Rule, was of mixed Spanish, African and Native American ancestry. Pico spent his last days in Los Angeles, dying in 1894 at the home of his daughter Joaquina Pico Moreno in Los Angeles. He was buried in the old Calvary Cemetery on North Broadway in Downtown Los Angeles, before his remains were relocated.

Blacks and mulattoes did not face legal discrimination until after California was handed over to the United States in 1848. Many white Southerners who came to California during the Gold Rush brought with them racist attitudes and ideals. In 1850, there were twelve black people registered as residents of Los Angeles. Because many blacks were enslaved until abolition in 1865, few blacks migrated to Los Angeles before then. Due to the construction of the Santa Fe Railroad and a settlement increase in 1880, increasing numbers of blacks came to Los Angeles. By 1900, 2,131 African-Americans, the second largest black population in California, lived in Los Angeles.[1]

In 1872, the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles (First A.M.E. or FAME) was established under the sponsorship of Biddy Mason, an African American nurse and a California real estate entrepreneur and philanthropist, and her son-in-law Charles Owens. The church now has a membership of more than 19,000 individuals.

The first branch of the NAACP in California was established in Los Angeles in 1913.

From approximately 1920 to 1955, Central Avenue was the heart of the African-American community in Los Angeles, with active rhythm and blues and jazz music scenes.

Jazz legend Charles Mingus was born in Los Angeles in 1922. Raised largely in the Watts area of Los Angeles, he recorded in a band in Los Angeles in the 1940s.

In 1928, World War I veteran William J. Powell founded the Bessie Coleman Aero Club. In 1931, Powell organized the first all-black air show in the United States for the Club in Los Angeles, an event that drew 15,000 visitors. Powell also established a school to train mechanics and pilots.

Singer-songwriter Ray Charles moved to Los Angeles in 1950. In 2004, his music studio on Washington Blvd. in Los Angeles was declared a historic landmark.

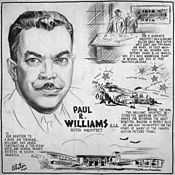

The Theme Building, an iconic landmark structure at the Los Angeles International Airport, opened. The structure was designed by a team of architects and engineers headed by William Pereira and Charles Luckman, that also included Paul Williams and Welton Becket. Born in Los Angeles in 1894, Williams studied at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and at the Los Angeles branch of the New York Beaux-Arts Institute of Design Atelier, subsequently working as a landscape architect. He went on to attend the University of Southern California, School of Engineering, designing several residential buildings while still a student there. Williams became a certified architect in 1921, and the first certified African-American architect west of the Mississippi.

In 1954, Dorothy Dandridge (who was originally from Ohio but settled in Los Angeles) became the first black actress to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in the 1954 film Carmen Jones. Many years passed before the entertainment industry acknowledged Dandridge's legacy. Starting in the 1980s, stars such as Cicely Tyson, Jada Pinkett Smith, Halle Berry, Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Kimberly Elise, Loretta Devine, Tasha Smith, and Angela Bassett acknowledged Dandridge's contributions to the role of black Americans in film.

The Watts Riots took place in 1965.

In 1966, Mervyn Dymally, a Los Angeles teacher and politician, became the first African American to serve in the California State Senate. He went on to be elected as Lieutenant Governor in 1974.

Also in 1966, Yvonne Brathwaite Burke, an attorney from Los Angeles, became the first African American woman in the California Legislature and in 1972 became the first African American woman elected to the U.S. Congress from the West Coast. She served in Congress from 1973 until the end of 1978.

In 1973, Tom Bradley was elected as Mayor of Los Angeles, a role he'd hold for 20 years. L.A.'s first African American mayor, Bradley served over five terms, prior to the establishment of successive term limits, making him the longest-serving mayor of Los Angeles.

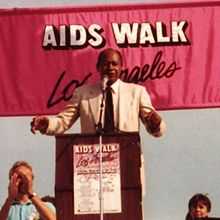

In 1981, two years after being drafted into the Los Angeles Lakers, Magic Johnson signed a 25-year, $25-million contract with the Lakers, which was the highest-paying contract in sports history up to that point. Johnson's career was closely followed by the media and he became a favorite among Los Angeles sports fans. Among his many achievements are three NBA MVP Awards, nine NBA Finals appearances, twelve All-Star games, ten All-NBA First and Second Team nominations and he is the NBA's all-time leader in average assists per game, at 11.2. Since his retirement, Johnson has been an advocate for HIV/AIDS prevention and safe sex, as well as an entrepreneur, philanthropist, broadcaster and motivational speaker. Named by Ebony Magazine as one of America's most influential black businessmen in 2009, Johnson has numerous business interests, and was a part-owner of the Lakers for several years. Johnson also is part of a group of investors that purchased the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2012 and the Los Angeles Sparks in 2014.

Carl Lewis came to prominence at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, winning four gold medals, matching Jesse Owens’ legendary feat of winning four gold medals at the 1936 Olympics. Lewis was one of the biggest sporting celebrities in the world by the start of 1984, but owing to track and field’s relatively low profile in America, Lewis was not nearly as well known there.

In 1988, Florence Griffith Joyner (also known as Flo-Jo), born and raised in Los Angeles, and a UCLA graduate, won three gold medals at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul. She is considered the fastest woman of all time based on the fact that the world records she set in 1988 for both the 100m and 200m still stand and have yet to be seriously challenged.

In 1991, Rodney King was beaten by police officers. His videotaped beating was controversial, and heightened racial tensions in Los Angeles. Just 13 days after the videotaped beating of King, a 15-year-old African-American girl named Latasha Harlins was unlawfully shot and killed by a 51-year-old Korean store owner named Soon Ja Du. A jury found Du guilty of voluntary manslaughter, an offense that carries a maximum prison sentence of 16-years. However, trial judge, Joyce Karlin, sentenced Du five years of probation, four hundred hours of community service, and a $500 fine. When four Los Angeles Police Department officers were acquitted of charges associated with the beating of Rodney King, the decision led to the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

In 1993, Etta James was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Known as the "The Matriarch of R&B", James is regarded as having bridged the gap between rhythm and blues and rock and roll, and is the winner of six Grammys and 17 Blues Music Awards. She was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2001, and the Grammy Hall of Fame in both 1999 and 2008. James was born the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, and received her first professional vocal training at age five from James Earle Hines, musical director of the Echoes of Eden choir, at the St. Paul Baptist Church in South Central.

The trial of the O. J. Simpson murder case took place in 1994.

In 2002, Serena Williams, raised in Los Angeles, became the Women's Tennis Association's World No. 1 player. Williams is regarded by some experts and former tennis players to be the greatest female tennis player in history. She has won four Olympic gold medals and is the only female player to have won over $60 million in prize money. Williams is the reigning US Open, WTA Tour Championships and Olympic ladies singles champion.

Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Demographics

In 2007, 4% of African-American adults in Los Angeles County identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.[2]

Most black LGB persons live in black neighborhoods. Of black LGB persons, 38% lived in South Los Angeles, 33% lived in the South Bay, and less than 1% lived in the Los Angeles Westside. Mignon R. Moore, the author of "Black and Gay in L.A.: The Relationships Black Lesbians and Gay Men Have to Their Racial and Religious Communities," wrote that black LGB people had a tendency to not have openness about their sexuality and to not discuss their sexuality, and also that "they were not a visible group in neighborhoods like Carson and Ladera Heights".[2]

Geography

In 2001, within the Los Angeles metropolitan area, Compton, Ladera Heights, and View Park have the highest concentration of blacks. The cities of Malibu and Newport Beach have the lowest concentrations of blacks. As of 2001, in the majority of cities within Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura counties had black populations below 10%.[3] From 1990 to 2010 the population of Compton, previously African-American, changed to being about 66% Latino and Hispanic.[4]

Philip Garcia, a population specialist and the assistant director of institutional research for California State University, stated that a group of communities in South Los Angeles became African-American by the 1950s and 1960s. These communities were Avalon, Baldwin Hills, Central, Exposition Park, Santa Barbara, South Vermont, Watts, and West Adams. Since then the Santa Barbara street was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.[5] 98,685 blacks moved to Los Angeles in the period 1965 through 1970. During the same period 40,776 blacks moved out.[6]

Between 1975 and 1980, 96,833 blacks moved to Los Angeles while 73,316 blacks left Los Angeles. Over 5,000 of the blacks moved to the Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario area. About 2,000 to 5,000 blacks moved to the Anaheim-Santa Ana-Garden Grove area. James H. Johnson, a University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) associate professor of geography, stated that due to affordable housing, blacks tend to choose "what is called the balance of the counties" or cities neutral to the existing major cities.[6] In the Inland Empire, blacks tended to move to Rialto instead of Riverside and San Bernardino.[6]

Of the blacks who left the City of Los Angeles between 1975 and 1980 who moved away from the Los Angeles area, over 5,000 moved to the Oakland, California area, about 2,000-5,000 went to San Diego, about 1,000-2,000 went to Sacramento, and about 1,000 to 2,000 went to San Jose, California. About 500 to 1,000 blacks moved to Fresno, Oxnard, Santa Barbara, Simi Valley, and Ventura. Johnson stated that the areas from Fresno to Ventura are "areas that traditionally blacks haven't settled in".[6] Many blacks leaving Los Angeles who also California moved to cities in the U.S. South, including Atlanta, Houston, Little Rock, New Orleans, and San Antonio. Other cities receiving LA blacks include Chicago, New York City, and Las Vegas.[6]

In the 1990s, many African Americans moved away from the traditional African-Americans neighborhoods, which overall reduced the black population of the City of Los Angeles and Los Angeles County. Many African Americans moved to eastern Los Angeles suburbs in Riverside County and San Bernardino County in the Inland Empire, such as Moreno Valley.[3] From 1980 to 1990 the Inland Empire had the United States's fastest-growing black population. Between the 1980 U.S. Census and the 1990 U.S. Census, the black population increased by 119%. As of 1990 the Inland Empire had 169,128 black people.[7]

Many new African-American businesses appeared in the Inland Empire, and many of these businesses had not been previously established elsewhere. The Inland Empire African American Chamber of Commerce began with six members in 1990 and the membership increased to 90 by 1996. According to Denise Hamilton of the Los Angeles Times, as of 1996 "there has been no large-scale migration from the traditional black business districts such as Crenshaw, black business people say."[7] During the 1990s, the black population of the Moreno Valley increased by 27,500,[3] and by 1996 13% of Moreno Valley was African American.[7]

In addition, in the 1990s many African Americans moved to cities and areas in north Los Angeles County such as Lancaster and Palmdale and closer-in cities in Los Angeles County such as Hawthorne and Long Beach. In the 1990s, the black population of Long Beach increased by 66,800.[3]

Health care

Martin Luther King, Jr. Multi-Service Ambulatory Care Center in Willowbrook, previously the King-Drew Hospital, opened in 1972 to serve the surrounding areas of South Los Angeles, partially as a response to complaints that came to light during the Watts Riots about the area having inadequate and insufficient hospital facilities.[8]

Notable residents

- Tom Bradley (Mayor of Los Angeles)

- Nat King Cole

- Larry Elder

- Florence Griffith Joyner

- Rodney King

- Tim Moore (comedian)

- O.J. Simpson

- Tavis Smiley

- Maxine Waters

References

- Moore, Mignon R. "Black and Gay in L.A.: The Relationships Black Lesbians and Gay Men Have to Their Racial and Religious Communities" (Chapter 7). In: Hunt, Darnell and Ana-Christina Ramon (editors). Black Los Angeles: American Dreams and Racial Realities. NYU Press, April 19, 2010. ISBN 0814773060, 9780814773062.

- Stanford, Karin L. African Americans in Los Angeles. Arcadia Publishing, 2010. ISBN 0738580945, 9780738580944.

Notes

- ↑ Stanford, p. 7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Moore, p. 190.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Texeira, Erin. "Migrants From L.A. Flow to Affordable Suburbs Such as Inland Empire." Los Angeles Times. March 30, 2001. Retrieved on April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Simmons, Ann M. and Abby Sewell. "Suit seeks to open Compton to Latino voters." Los Angeles Times. December 20, 2010. Retrieved on April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Martinez, Diana. "A Changing Population in South-Central L.A., Watts." Los Angeles Times. January 17, 1991. Retrieved on April 3, 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 McMillan, Penelope. "'Black Flight' From L.A. Reverses Trend, Study Discovers." Los Angeles Times. September 22, 1987. Retrieved on July 1, 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hamilton, Denise. "Land of Opportunity : Land of Opportunity." Los Angeles Times. December 22, 1996. Retrieved on April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Landsberg, Mitchell. "Why supervisors let deadly problems slide." Los Angeles Times. December 9, 2004. p. 1. Retrieved on April 16, 2014.

Further reading

- Flamming, Douglas. Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America (The George Gund Foundation imprint in African American studies). University of California Press, August 1, 2006. ISBN 0520249909, 9780520249905.

- Hunt, Darnell and Ana-Christina Ramón (editors). Black Los Angeles: American Dreams and Racial Realities. NYU Press, April 19, 2010. ISBN 0814773060, 9780814773062.

- Kurashige, Scott. The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles. Princeton University Press, March 15, 2010. ISBN 1400834007, 9781400834006.

- Pulido, Laura. Black, Brown, Yellow, and Left: Radical Activism in Los Angeles (Volume 19 of American crossroads). University of California Press, January 1, 2006. ISBN 0520245202, 9780520245204.

- Sides, Josh. L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present. University of California Press, June 1, 2006. ISBN 0520248309, 9780520248304.

- Sonenshein, Raphael. Politics in Black and White: Race and Power in Los Angeles. Princeton University Press, 1993. ISBN 0691025487, 9780691025483.

- Tolbert, Emory J. The UNIA and Black Los Angeles: ideology and community in the American Garvey movement (Volume 3 of A CAAS monograph series, Volume 3 of Afro-American culture and society). Center for Afro-American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles, 1980. ISBN 0934934045, 9780934934046.

- Widener, Daniel. Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles. Duke University Press, January 1, 2009.

| ||||||