History of leprosy

Using comparative genomics in 2005, geneticists traced the origins and worldwide distribution of leprosy from East Africa or the Near East along human migration routes. They found that there were four strains of M. leprae with specific regional locations. Strain 1 occurs predominately in Asia, the Pacific region, and East Africa; strain 4, in in West Africa and the Caribbean; strain 3 in Europe, North Africa, and the Americas; and strain 2 only in Ethiopia, Malawai, Nepal/north India, and New Caledonia.

On the basis of this, they offer a map of the dissemination of leprosy in the world. This confirm the spread of the disease along the migration, colonisation, and slave trade routes taken from West Africa to India, East Africa to the New World, and from Africa into Europe and vice versa.[1]

In spite of persistent claims from retrospective interpretations of the symptoms of leprosy in ancient Indian, Greek, and Middle Eastern documentary sources that describe skin afflictions, the skeletal remains from the second millennium B.C., discovered in 2009, represent the oldest documented evidence for leprosy. Located at Balathal, in Rajasthan, northwest India, the discoverers suggest that if the disease did migrate from Africa, to India, during the third millennium B.C. “at a time when there was substantial interaction among the Indus Civilization, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, there needs to be additional skeletal and molecular evidence of leprosy in India and Africa so as to confirm the African origin of the disease.” [2]

Although it is difficult to retrospectively identify descriptions of leprosy-like symptoms, what appears to be leprosy was discussed by Hippocrates in 460 BC.[53] Documentary evidence also indicates that it was recognized in the civilizations of ancient China, Egypt, Israel, and India.[22] In 1846, Francis Adams produced The Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta which included a commentary on all medical and surgical knowledge and descriptions and remedies from the Romans, Greeks, and Arabians.[3][4] A proven human case was verified by DNA taken from the shrouded remains of a man discovered in a tomb next to the Old City of Jerusalem dated by radiocarbon methods to 1–50 AD.[54][5]

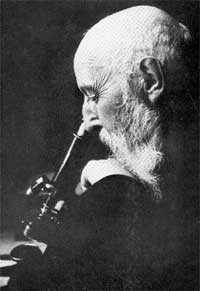

The causative agent of leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae, was discovered by G. H. Armauer Hansen in Norway in 1873, making it the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans.[6] The first effective treatment (promin) became available in the 1940s.[7] The search for further effective anti-leprosy drugs led to the use of clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s.[8] Later, Indian scientist Shantaram Yawalkar and his colleagues formulated a combined therapy using rifampicin and dapsone, intended to mitigate bacterial resistance.[9] Multidrug therapy (MDT) combining all three drugs was first recommended by the WHO in 1981. These three anti-leprosy drugs are still used in the standard MDT regimens.

Discovery

After the end of the 17th century, Norway, Iceland and England were the countries in Western Europe where leprosy was a significant problem. During the 1830s, the number of lepers in Norway, Iceland and England rose rapidly, believed to be caused by frequent visits of sailors who visited Western India, causing an increase in medical research into the condition, and the disease became a political issue. Norway appointed a medical superintendent for leprosy in 1854 and established a national register for lepers in 1856, the first national patient register in the world.[10]

Mycobacterium leprae, the causative agent of leprosy, was discovered by G. H. Armauer Hansen in Norway in 1873, making it the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans.[6][11] The principal opposition to Hansen's view that leprosy was an infectious disease came from his father-in-law, Daniel Cornelius Danielssen who considered it a hereditary disease and had stated this in his book, "Traité de la Spedalskhed ou Elephantiasis des Grecs"—the standard reference book on leprosy from 1848 until the death of Danielssen in 1895.[12] While Danielssen's book in 1847 was a highly used source and provided a solid foundation for worldwide leprosy understanding, it was soon surpassed. In 1867 Dr. Gavin Milroy finished the Royal College of Physicians' Report on leprosy. His work, which compiled data from all corners of the English empire, agreed with Danielssen that leprosy was a hereditary disease, but went further to state that leprosy was also a constitutional disease that could be mitigated by improvements in one's health, diet, and living conditions.[13]

Hansen observed a number of nonrefractile small rods in unstained tissue sections. The rods were not soluble in potassium lye, and they were acid- and alcohol-fast. In 1879, he was able to stain these organisms with Ziehl's method and the similarities with Koch's bacillus (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) were noted. There were three significant differences between these organisms: (1) the rods in the leprosy lesions were extremely numerous, (2) they formed characteristic intracellular collections (globii), and (3) the rods had a variety of shapes with branching and swelling. These differences suggested that leprosy was caused by an organism related to but distinct from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. He worked at St. Jørgens Hospital in Bergen, founded early in the fifteenth century. St. Jørgens is now preserved as a museum, Lepramuseet.[14]

Etymology

The word leprosy comes from ancient Greek Λέπρα [léprā], "a disease that makes the skin scaly", in turn, a nominal derivation of the verb Λέπω [lépō], "to peel, scale off". Λέπος (Lepos) in ancient Greek means peel, or scale, so from Λέπος we have Λεπερός (Λεπερός = who has peels—scales) --> and then Λεπρός(=leprous).[15] The word came into the English language via Latin and old French. The first attested English use is in the Ancrene Wisse, a 13th-century manual for nuns ("Moyseses hond..bisemde o þe spitel uuel & þuhte lepruse." The Middle English Dictionary, s.v., "leprous"). A roughly contemporaneous use is attested in the Anglo-Norman Dialogues of Saint Gregory, "Esmondez i sont li lieprous" (Anglo-Norman Dictionary, s.v., "leprus").

Throughout history, individuals with leprosy have been known as lepers; however, this term is falling into disuse as a result of the diminishing number of leprosy patients. Because of the stigma to patients, some prefer not to use the word "leprosy," though the term is used by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.[16]

In particular, tinea capitis (fungal scalp infection) and related infections on other body parts caused by the dermatophyte fungus Trichophyton violaceum are abundant throughout the Middle East and North Africa today and might also have been common in biblical times. Likewise, the related agent of the disfiguring skin disease favusTrichophyton schoenleinii appears to have been common throughout Eurasia and Africa before the advent of modern medicine. Persons with severe favus and similar fungal diseases (and potentially also with severe psoriasis and other diseases not caused by microorganisms) tended to be classed as having leprosy as late as the 17th century in Europe.[17] This is clearly shown in the painting The Regents of the Leper Hospital in Haarlem 1667 by Jan de Bray (Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, the Netherlands), where a young Dutchman with a vivid scalp infection, it is presumed caused by a fungus, is shown being cared for by three officials of a charitable home intended for leprosy sufferers. The use of the word "leprosy" before the mid-19th century, when microscopic examination of skin for medical diagnosis was first developed, can seldom be correlated reliably with leprosy as we understand it today.

"Leprosy" in the Bible

Many English translations of the Bible translate tzaraath as "leprosy," a confusion that derives from the use of the koine cognate "Λέπρα" (which can mean any disease causing scaly skin) in the Septuagint. Ancient sources such as the Talmud (Sifra 63) make clear that tzaraath refers to various types of lesions or stains associated with ritual impurity and occurring on cloth, leather, or houses as well as skin. While it may sometimes be a symptom of the disease described in this article, it has many other causes as well.

Historical treatments

The disease was known in Ancient Greece as elephantiasis (elephantiasis graecorum). At various times blood was considered to be a treatment either as a beverage or as a bath. That of virgins or children was considered to be especially potent. This practice seems to have originated with the Ancient Egyptians but was also known in China. This practice persisted until at least 1790, when the use of dog blood was mentioned in De Secretis Naturae. Paracelsus recommended the use of lamb's blood and even blood from dead bodies was used.

Snakes were also used, according to Pliny, Aretaeus of Cappadocia, and Theodorus. Gaucher recommended treatment with cobra venom. Boinet, in 1913, tried increasing doses of bee stings (up to 4000). Scorpions and frogs were used occasionally instead of snakes. The excreta of Anabas (the climbing fish) was also tried.

Alternative treatments included scarification with or without the addition of irritants including arsenic and hellebore. Castration was also practiced in the Middle Ages.

A common pre-modern treatment of leprosy was chaulmoogra oil.

The oil has long been used in India as an Ayurvedic medicine for the treatment of leprosy and various skin conditions. It has also been used in China and Burma, and was introduced to the West by Frederic John Mouat, a professor at Bengal Medical College. He tried the oil as an oral and topical agent in two cases of leprosy and reported significant improvements in an 1854 paper.[19]

This paper caused some confusion. Mouat indicated that the oil was the product of a tree Chaulmoogra odorata, which had been described in 1815 by William Roxburgh, a surgeon and naturalist, while he was cataloging the plants in the East India Company’s botanical garden in Calcutta. This tree is also known as Gynocardia odorata. For the rest of the 19th century, this tree was thought to be the source of the oil. In 1901, Sir David Prain identified the true chaulmoogra seeds of the Calcutta bazaar and of the Paris and London apothecaries as coming from Taraktogenos kurzii, which is found in Burma and Northeast India. The oil mentioned in the Ayurvedic texts was from the tree Hydnocarpus wightiana, known as Tuvakara in Sanskrit and chaulmugra in Hindi and Persian.

The first parenteral administration was given by the Egyptian doctor Tortoulis Bey, personal physician to the Sultan Hussein Kamel of Egypt. He had been using subcutaneous injections of creosote for tuberculosis and in 1894 administered subcutaneous injection of chaulmoogra oil in a 36-year-old Egyptian Copt who had been unable to tolerate oral treatment. After 6 years and 584 injections, the patient was declared cured.

An early scientific analysis of the oil was carried out by Frederick B. Power in London in 1904. He and his colleagues isolated a new unsaturated fatty acid from the seeds, which they named 'chaulmoogric acid'. They also investigated two closely related species: Hydnocarpus anthelmintica and Hydnocarpus wightiana. From these two trees they isolated both chaulmoogric acid and a closely related compound, 'hydnocarpus acid'. They also investigated Gynocardia odorata and found that it produced neither of these acids. Later investigation showed that 'taraktogenos' (Hydnocarpus kurzii) also produced chaulmoogric acid.

Another difficulty with the use of this oil was administration. Taken orally it is extremely nauseating. Given by enema may cause peri-anal ulcers and fissures. Given by injection the drug caused fever and other local reactions. Despite these difficulties, a series of 170 patients were reported in 1916 by Ralph Hopkins, the attending physician at the Louisiana Leper Home in Carville, Louisiana. He divided the patients into two groups - 'incipient' and 'advanced'. In the advanced cases, 25% (at most) showed any improvement or arrest of their condition; in the incipient cases, 45% reported an improvement or stabilization of the disease (mortality rates were 4% and 8%, respectively). The remainder absconded from the Home apparently in improved condition.

Given the apparent usefulness of this agent, a search began for improved formulations. Victor Heiser the Chief Quarantine Officer and Director of Health for Manila and Elidoro Mercado the house physician at the San Lazaro Hospital for lepers in Manila decided to add camphor to a prescription of chaulmoogra and resorcin, which was typically given orally at the suggestion of Merck and Company in Germany to whom Heiser had written. They found that this new compound was readily absorbed without the nausea that had plagued the earlier preparations.

Heiser and Mercado in 1913 then administered the oil by injection to two patients who were cured of the disease. Since this treatment was administered in conjunction with other materials, the results were not clear. A further two patients were treated with the oil by injection without other treatments and again appeared to be cured of the disease. The following year, Heiser reported a further 12 patients but the results were mixed.

Less toxic injectable forms of this oil were then sought. Between 1920 and 1922, a series of papers were published describing the esters of these oils. These may have been based on the work of Alice Ball—the record is not clear on this point and Ms Ball died in 1916. Trials of these esters were carried out in 1921 and appeared to give useful results.

These attempts had been preceded by others. Merck of Darmstadt had produced a version of the sodium salts in 1891. They named this sodium gynocardate in the mistaken belief that the origin of the oil was Gynocardia odorata. Bayer in 1908 marketed a commercial version of the esters under the name 'Antileprol'.

To ensure a supply of this agent Joseph Rock, Professor of Systematic Botany at the College of Hawaii, traveled to Burma. The local villagers located a grove of trees in seed, which he used to establish a plantation of 2,980 trees on the island of Oahu, Hawaii between 1921 and 1922.

The oil remained a popular treatment despite the common side effects until the introduction of sulfones in the 1940s. Debate about its efficacy continued until it was discontinued.

Asylums

Contrary to popular opinion, people were not universally isolated in leprosy asylums in the Middle Ages. In Europe, asylums offered shelter to all manner of people, including some who would have had skin complaints that included leprosy. Neither was the expansion of asylums in England between 1100 and 1250 necessarily in response to a major epidemic of leprosy.[20](346)

Additionally, leprosy did not simply and unaccountably disappear in Europe after the medieval period as a result of a “great confinement” of leprosy-affected people in leprosy asylums. In Portugal, for example, there were still 466 cases, in 1898, and there were sufficient numbers in Portugal in 1938 to warrant the construction of Rovisco Pais, to treat people affected by the disease.[21] This was not only for those returning from the New World, but also for rural dwellers infected in Portugal itself, as the records of Rovisco Pais demonstrate. In Spain too, leprosy was a matter for public attention. In 1902, Jesuits, Father Carlos Ferris and Joaquin Ballister, founded the Patronato San Francisco de Borja, Fontilles. In 1904, there were still 552 cases and over 1,000 estimated in Spain.[22] The presence of the disease in these two countries supports the genetic tracking carried out by Monot et al that traces exchanges along the trade and slave routes from Africa, to Spain and Portugal, to the West Indies, and back again to Spain and Portugal, while at the same time, an autochthonous presence persisted from an earlier period.

Numerous leprosaria, or leper hospitals, sprang up in the Middle Ages; Matthew Paris, a Benedictine Monk, estimated that in the early thirteenth century there were 19,000 across Europe.[23] The first recorded Leper colony was in Harbledown, England. While leprosaria were common throughout Europe in the early, middle, and late Middle Ages, how leprosy was dealt with in the Middle Ages is still viewed through the “distorting lens” of “nineteenth century attempts by physicians, polemicist, and missionaries” who tried to use “the past for evidence to support their own campaigns for mandatory segregation.” [24] The leprosy asylum or leprosarium of the past had many designations and variations in structure and degree of restriction. In the medieval period it offered support to many indigent people, amongst whom, some would have suffered from leprosy. In England, these houses were run along monastic lines and required those admitted to take vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity.[25] Those flouting the rules could be expelled. The disease took on symbolic significance within the Christian framework. Withdrawal from everyday life was considered symbolic of ritually separate themselves from the world of the flesh, as a redemptive action, on behalf of the whole of society.[20][26]

The Order of Saint Lazarus was a hospitaller and military order of monks that began as a leper hospital outside Jerusalem in the twelfth century and remained associated with leprosy throughout its history. The first monks in this order were leper knights, and they originally had leper grand masters, although these aspects of the order changed over the centuries.

Radegund was noted for washing the feet of lepers. Orderic Vitalis writes of a monk, Ralf, who was so overcome by the plight of lepers that he prayed to catch leprosy himself (which he eventually did). The leper would carry a clapper and bell to warn of his approach, and this was as much to attract attention for charity as to warn people that a diseased person was near.

The leprosaria of the Middle Ages had multiple benefits: they provided treatment and safe living quarters for people with leprosy who were granted admission; they eased tension amongst the healthy townspeople; and they provided for a more stable populace for the authorities to govern.[13][27]

Modern treatments

It has been said that Promin was first synthesised in 1940 by Feldman of Parke-Davis and company.[28] Although Parke-Davis did in fact synthesise the compound, it seems certain that they were not the first. In the same year that Gelmo described sulphanilamide (1908), Emil Fromm, who was the professor of chemistry in the medical faculty of the University of Freiburg im Breisgau, in Germany, described another compound related to the sulphonamides: this was diaminodiphenylsulphone or dapsone (DDS). No one recognised the potential of this compound, until Buttle and his colleagues at the Wellcome laboratories and Fourneau and the researchers at the Institut Pasteur simultaneously found that dapsone was ten times as potent against streptococcal infection in mice and about a hundred times as toxic as sulphanilamide in 1937.[29]

Until the introduction of treatment with promin in the 1940s, there was no effective treatment for leprosy. The efficacy of promin was first discovered by Guy Henry Faget and his co-workers in 1943 at Carville, Louisiana. Robert Cochrane was the first to use DDS, the active component of Promin, at the Lady Willingdon Leprosy Settlement, in Chingleput, outside of Madras, in India, and John Lowe was the first to successfully administrated DDS orally, in spite of all the indications that the drug was highly toxic, at Uzuakoli leprosy colony, in Nigeria. Both innovations would make it possible to produce a treatment that was cheap, seemingly effective, and could be made available on a large scale.

Scientists eventually realised that DDS was only weakly bactericidal against M. leprae and it was considered necessary for patients to take the drug indefinitely. When dapsone was used alone, the M. leprae population quickly evolved antibiotic resistance; by the 1960s, the world's only known anti-leprosy drug became ineffective against resistant bacteria.

The search for more effective anti-leprosy drugs led to the use of clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s.[8] Later, Indian scientist Shantaram Yawalkar and his colleagues formulated a combined therapy using rifampicin and dapsone, intended to mitigate bacterial resistance.[9] The first trials of combined treatment were carried out in Malta in the 1970s.

Multidrug therapy (MDT) combining all three drugs was first recommended by a WHO Expert Committee in 1981. These three anti-leprosy drugs are still used in the standard MDT regimens. None of them is used alone because of the risk of developing resistance.

This treatment was quite expensive, and was not quickly adopted in most endemic countries. In 1985, leprosy was still considered a public health problem in 122 countries. The 44th World Health Assembly (WHA), held in Geneva in 1991, passed a resolution to eliminate leprosy as a public-health problem by the year 2000 — defined as reducing the global prevalence of the disease to less than 1 case per 10,000. At the Assembly, the World Health Organization (WHO) was given the mandate to develop an elimination strategy by its member states, based on increasing the geographical coverage of MDT and patients’ accessibility to the treatment. The medication is made available freely by Novartis.

Iran

The Persian polymath Avicenna (c. 980–1037) was the first outside of China to describe the destruction of the nasal septum in those suffering from leprosy.[30]

India

The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine holds that the mention of leprosy, as well as cures for it, were already described in the Hindu religious book Atharva-veda.[31] Writing in the Encyclopædia Britannica 2008, Kearns & Nash state that the first mention of leprosy is in the Indian medical treatise Sushruta Samhita (6th century BC).[32] The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology (1998) holds that: "The Sushruta Samhita from India describes the condition quite well and even offers therapeutic suggestions as early as about 600 BC"[33] The surgeon Sushruta lived in the Indian city of Kashi by the 6th century BC,[34] and the medical treatise Sushruta Samhita—attributed to him—made its appearance during the 1st millennium BC.[32] The earliest surviving excavated written material that contains the works of Sushruta is the Bower Manuscript—dated to the 4th century AD, almost a millennium after the original work.[35] Despite the existence of these earlier works the first generally considered accurate description of the disease was that of Galen of Pergamum in 150 AD.

In 2009, a 4,000-year-old skeleton was uncovered in India that was shown to contain traces of leprosy.[36] The discovery was made at a site called Balathal, which is today part of Rajasthan, and is believed to be the oldest case of the disease ever found.[37] This pre-dated the previous earliest recognized case, dating back to 6th-century Egypt, by 1,500 years.[38] It is believed that the excavated skeleton belonged to a male, who was in his late 30s and belonged to the Ahar Chalcolithic culture.[38][39] Archaeologists have stated that not only does the skeleton represent the oldest case of leprosy ever found, but is also the first such example that dates back to prehistoric India.[40] This finding supports one of the theories regarding the origin of the disease, which is believed to have originated in Africa.

In 1874, the Missions to Lepers began to offer support to leprosy asylums that offered shelter to people affected by leprosy in India. Gradually, they instituted a policy of segregating males and females in the institutions.[41] The asylum superintendents believe that this separation was beneficial in order to avoid infecting the children of diseased parents and to prevent further births. At this time, there were still debates about the transmission of the disease, but the Leprosy Mission were heartened to find that the separated children did not develop the disease.[42]

In 1881, around 120,000 leprosy patients existed in India. The central government passed the Lepers Act of 1898, which provided legal provision for forcible confinement of leprosy sufferers in India, but the Act was not enforced.[43][44]

China

Regarding ancient China, Katrina C. D. McLeod and Robin D. S. Yates identify the State of Qin's Feng zhen shi 封診式 (Models for sealing and investigating), dated 266-246 BC, as offering the earliest known unambiguous description of the symptoms of low-resistance leprosy, even though it was termed then under li 癘, a general Chinese word for skin disorder.[30] This 3rd-century BC Chinese text on bamboo slip, found in an excavation of 1975 at Shuihudi, Yunmeng, Hubei province, described not only the destruction of the "pillar of the nose" but also the "swelling of the eyebrows, loss of hair, absorption of nasal cartilage, affliction of knees and elbows, difficult and hoarse respiration, as well as anesthesia."[30]

Indonesia

Across Indonesia the rate of prevalence is slightly under one new case per 10,000 people, with approximately 20,000 new cases detected each year.[45] However, the rate is considerably higher in particular regions, particularly South Sulawesi (with more than three new cases per 10,000 people) and North Maluku (with more than five new cases per ten thousand people).[45] MDT is provided free of charge to patients who require it in Indonesia and there are a number of hospitals in major population centers specifically intended to deal with the medical needs of those affected by the disease.[45] While the early detection and treatment of leprosy has certainly improved over the years, approximately ten percent of patients in Indonesia have already suffered significant nerve or other damage prior to the identification and treatment of their disease, largely due to lack of awareness and to a pervasive stigma that discourages those with the disease from coming forward to seek treatment.[45]

PERMATA (Perhimpunan Mandiri Kusta) Indonesia was established in 2007 with the specific vision of fighting the stigma associated with leprosy and eliminating the discrimination against those identified as suffering from the disease. The organization was founded by a small group of individuals who had all personally been treated for leprosy. The founders worked to establish links with key figures amongst those suffering from the disease in communities in South Sulawesi, East Java and NTT, the three provinces where the rate of incidence of the disease is probably amongst the highest in Indonesia.[46]

Japan

Japan has had a unique history of segregation of patients into sanatoria based on leprosy prevention laws of 1907, 1931, and 1953, and, hence, it intensified leprosy stigma. The 1953 law was abrogated in 1996. There were still 2717 ex-patients in 13 national sanatoria and two private hospitals as of 2008. In a document written in 833, leprosy was described as "caused by a parasite that eats five organs of the body. The eyebrows and eyelashes come off, and the nose is deformed. The disease brings hoarseness, and necessitates amputations of the fingers and toes. Do not sleep with the patients, as the disease is transmittable to those nearby." This was the first document concerning infectivity.[47] Males admitted to leprosaria in Japan were sterilized and females found to be pregnant were forced to have abortions. These extreme actions were done to prevent children of diseased parents from being born lest they also contract the disease. Doctors during this time still mistakenly believed that leprosy was a hereditary disease.[48] Lepers were seen as being incurable and infectious, the main reason they were forced into exile.

References

- ↑ Marc Monot, Nadine Honoré, Thierry Garnier, Romul Araoz, Jean-Yves Coppée, Céline Lacroix, Samba Sow, John S Spencer, Richard W Truman, Diana L Williams, Robert Gelber, Marcos Virmond, Béatrice Flageul, Sang-Nae Cho, Baohong Ji, Alberto Paniz-Mondolfi, Jacinto Convit, Saroj Young, Paul E Fine, Voahangy Rasolofo, Patrick J Brennan, Stewart T Cole, “On the Origin of Leprosy”, Science 308. 5724 (13 May 2005), DOI: 10.1126/science/1109759

- ↑ Gwen Robbins, V. Mushrif Tripathy, V. N. Misra, R. K. Mohanty, V. S. Shinde, Kelsey M. Gray, and Malcolm D. Schug, “Ancient Skeletal Evidence for Leprosy in India (2000 B.C.)” PLOS, Published: May 27, 2009, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005669

- ↑ Francis Adams, The Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta: Translated from the Greek with Commentary Embracing a Complete View of the Knowledge Possessed by the Greeks, Romans and Arabians on All Subjects Connected with Medicine and Surgery, 3 vols. (London: Sydenham Society, 1846)

- ↑ Roman: Celsus, Pliny, Serenus Samonicus, Scribonius Largus, Caelius Aurelianus, Themison, Octavius Horatianus, Marcellus the Emperic; Greek: Aretaeus, Plutarch, Galen, Oribasius, Aetius, Actuarius, Nonnus, Psellus, Leo, Myrepsus; Arabic: Scrapion, Avenzoar, Albucasis, the Haly Abbas translated by Stephanus Antiochensis, Alsharavius, Rhases, and Guido de Cauliaco

- ↑ "DNA of Jesus-Era Shrouded Man in Jerusalem Reveals Earliest Case of Leprosy". ScienceDaily. 2009-12-16. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Irgens L (2002). "The discovery of the leprosy bacillus". Tidsskr nor Laegeforen 122 (7): 708–9. PMID 11998735.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guy_Henry_Faget

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rees RJ, Pearson JM, Waters MF; Pearson; Waters (1970). "Experimental and Clinical Studies on Rifampicin in Treatment of Leprosy". Br Med J 688 (1): 89–92. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5688.89. PMC 1699176. PMID 4903972.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Yawalkar SJ, McDougall AC, Languillon J, Ghosh S, Hajra SK, Opromolla DV, Tonello CJ; McDougall; Languillon; Ghosh; Hajra; Opromolla; Tonello (1982). "Once-monthly rifampicin plus daily dapsone in initial treatment of lepromatous leprosy". Lancet 8283 (1): 1199–1202. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92334-0. PMID 6122970.

- ↑ "The Leprosy Archives in Bergen, Norway". Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- ↑ Hansen GHA (1874). "Undersøgelser Angående Spedalskhedens Årsager (Investigations concerning the etiology of leprosy)". Norsk Mag. Laegervidenskaben (in Norwegian) 4: 1–88.

- ↑ Meyers, Wayne M. (1991). "Reflections on the International Leprosy Congresses and Other Events in Research, Epidemiology, and Elimination of Leprosy" (PDF). International Journal of Leprosy 62 (3): 412–427.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Edmond, Rod. Leprosy and Empire: A Medical and Cultural History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- ↑ "Bymuseet i Bergen". Bymuseet.no. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- ↑ Greek Dictionary Tegopoulos-Fytrakis, Athens, 1999

- ↑ "What Is Leprosy?" THE MEDICAL NEWS | from News-Medical.Net—Latest Medical News and Research from Around the World. Web. 20 Nov. 2010. <http://www.news-medical.net/health/What-is-Leprosy.aspx>.

- ↑ Kane J, Summerbell RC, Sigler L, Krajden S, Land G (1997). Laboratory Handbook of Dermatophytes: A clinical guide and laboratory manual of dermatophytes and other filamentous fungi from skin, hair and nails. Star Publishers (Belmont, CA). ISBN 0-89863-157-2. OCLC 37116438.

- ↑ Green, Monica H.; Walker-Meilke, Kathleen; Muller, Wolfgang P. (2014), "Diagnosis of a "plague" image: a digital cautionary tale" (PDF), The Medieval Globe 1: 309–326, ISBN 978-1-942401-04-9

- ↑ Indian Annals of Medical Science

- ↑ Carole Rawcliffe, Leprosy in Medieval England(Woodbridge, UK: Boydell P, 2006)

- ↑ Sir Leonard Rogers and Ernest Muir, 3rd ed., Leprosy (Bristol: Wright and Sons, 1946),22

- ↑ Sir Leonard Rogers and Ernest Muir, 3rd ed., Leprosy (Bristol: Wright and Sons, 1946),21

- ↑

"Leprosy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Leprosy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - ↑ Rawcliffe, 5

- ↑ Rawcliffe,7

- ↑ Brody, Saul Nathaniel The Disease of the Soul: Leprosy in Medieval Literature (Ithaca: Cornell Press, 1974).

- ↑ Leung, Angela Ki Che. Leprosy in China: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

- ↑ Ravina, E. and Kubinyi, H. (2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley \& Sons. p. 80. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- ↑ Wozel, Gottfried (1989). "The Story of Sulfones in Tropical Medicine and Dermatology". International Journal of Dermatology 28 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb01301.x. PMID 2645226.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 McLeod, Katrina C. D. and Robin D. S. Yates (June 1981). "Forms of Ch'in Law: An Annotated Translation of The Feng-chen shih". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 41 (1): 111–163. doi:10.2307/2719003. JSTOR 2719003. Angela Leung's Leprosy in China: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) is the authoritative source on leprosy in China.

- ↑ Lock et al; p. 420

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Kearns & Nash (2008)

- ↑ Aufderheide, A. C.; Rodriguez-Martin, C. & Langsjoen, O. (1998) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology. Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-55203-6; p. 148.

- ↑ Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007)

- ↑ Kutumbian, P. (2005) Ancient Indian Medicine. Orient Longman ISBN 81-250-1521-3; pp. XXXII-XXXIII

- ↑ Robbins G, Tripathy VM, Misra VN, Mohanty RK, Shinde VS, et al. (2009).Ancient Skeletal Evidence for Leprosy in India (2000 B.C.) PLoS ONE 4(5): e5669. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005669

- ↑ "Skeleton shows earliest evidence of leprosy". Associated Press. 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Skeleton Pushes Back Leprosy's Origins". Science Now. 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Shinde, Swati (2009-05-29). "Leprosy belonged to Ahar Chalcolithic era: Expert". The Times of India. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "'Oldest evidence of leprosy found in India'". The Times of India. 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Robertson, Jo. "The Leprosy Asylum in India: 1886–1947" Journal of the History of Medicine & Allied Sciences 64.4 (2009): 474–517. Print.

- ↑ Tony Gould, A Disease Apart: Leprosy in the Modern World. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2005). Print.

- ↑ Leprosy — Medical History of British India, National Library of Scotland

- ↑ Jane Buckingham,Leprosy in Colonial South India: Medicine and Confinement(Palgrave, Macmillan, 2001)

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 "Self-Care: Leprosy-related disabilities" in Invisible People: Poverty and Empowerment in Indonesia, Irfan Kortschak, 2010

- ↑ "Official Permata Website". Permata.or.id. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Kikuchi, Ichiro (1997). "Hansen's Disease in Japan: A Brief History". International Journal of Dermatology 36 (8): 629–633. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00230.x. PMID 9329899.

- ↑ McCurry, Justin (2004). "Japanese Leprosy Patients Continue to Fight Social Stigma". Lancet 363 (9408): 544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15586-4. PMID 14976977.

Further reading

- 1877: Lewis, T. R.; D. D. Cunningham (1877). Leprosy In India. Calcutta: Office Of The Superintendent Of Government Printing. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1895: Ashmead, Albert S. (1895). Pre-Columbian Leprosy. Chicago: American Medical Association Press. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1895: Prize Essays On Leprosy. London: The New Sydenham Society. 1895. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1896: Impey, S. P. (1896). A Handbook On Leprosy. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, Son & Co. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1916: Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (January 1916). "Fighting Leprosy In The Philippines". The World's Work: A History of Our Time XXXI: 310–320. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- 1991: William Jopling. Leprosy stigma. Lepr Rev 1991, 62, 1–12.

- 1993: Anne Bargès. Leprosy history and ethnology in Mali. In French.