History of fishing

Fishing is the activity of catching fish. It is an ancient practice dating back at least 40,000 years. Since the 16th century fishing vessels have been able to cross oceans in pursuit of fish and since the 19th century it has been possible to use larger vessels and in some cases process the fish on board. Fish are normally caught in the wild. Techniques for catching fish include hand gathering, spearing, netting, angling and trapping.

The term fishing may be applied to catching other aquatic animals such as shellfish, cephalopods, crustaceans, and echinoderms. The term is not usually applied to catching aquatic mammals, such as whales, where the term whaling is more appropriate, or to farmed fish. In addition to providing food, modern fishing is also a recreational sport.

According to FAO statistics, the total number of fishermen and fish farmers is estimated to be 38 million. Fisheries and aquaculture provide direct and indirect employment to over 500 million people.[1] In 2005, the worldwide per capita consumption of fish captured from wild fisheries was 14.4 kilograms, with an additional 7.4 kilograms harvested from fish farms.[2]

Prehistory

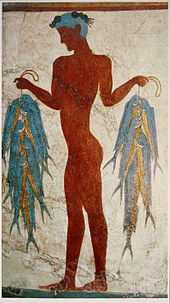

Fishing is an ancient practice that dates back at least to the Upper Paleolithic period which began about 40,000 years ago.[3][4] Isotopic analysis of the skeletal remains of Tianyuan man, a 40,000 year old modern human from eastern Asia, has shown that he regularly consumed freshwater fish.[5][6] Archaeological features such as shell middens,[7] discarded fish bones and cave paintings show that sea foods were important for survival and consumed in significant quantities. During this period, most people lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and were, of necessity, constantly on the move. However, where there are early examples of permanent settlements (though not necessarily permanently occupied) such as those at Lepenski Vir, they are almost always associated with fishing as a major source of food.

Spearfishing with barbed poles (harpoons) was widespread in palaeolithic times.[8] Cosquer cave in Southern France contains cave art over 16,000 years old, including drawings of seals which appear to have been harpooned.

The Neolithic culture and technology spread worldwide between 4,000 and 8,000 years ago. With the new technologies of farming and pottery came basic forms of the main fishing methods that are still used today.

From 7500 to 3000 years ago, Native Americans of the California coast were known to engage in fishing with gorge hook and line tackle.[9] In addition, some tribes are known to have used plant toxins to induce torpor in stream fish to enable their capture.[10]

Copper harpoons were known to the seafaring Harappans[11] well into antiquity.[12] Early hunters in India include the Mincopie people, aboriginal inhabitants of India's Andaman and Nicobar islands, who have used harpoons with long cords for fishing since early times.[13]

Ancient history

The ancient river Nile was full of fish; fresh and dried fish were a staple food for much of the population.[14] The Egyptians invented various implements and methods for fishing and these are clearly illustrated in tomb scenes, drawings, and papyrus documents. Simple reed boats served for fishing. Woven nets, weir baskets made from willow branches, harpoons and hook and line (the hooks having a length of between eight millimetres and eighteen centimetres) were all being used. By the 12th dynasty, metal hooks with barbs were being used. As is fairly common today, the fish were clubbed to death after capture. Nile perch, catfish and eels were among the most important fish. Some representations hint at fishing being pursued as a pastime.

|

|

From ancient representations and literature it is clear that fishing boats were typically small, lacking a mast or sail, and were only used close to the shore. There are numerous references to fishing in ancient literature; in most cases, however, the descriptions of nets and fishing-gear do not go into detail, and the equipment is described in general terms. An early example from the Bible in Job 41:7: Canst thou fill his skin with barbed irons? or his head with fish spears?. Traditional Chinese legends credit the art of fishing to Fu Xi.

Fishing scenes are rarely represented in ancient Greek culture, a reflection of the low social status of fishing in the region. There is a wine cup, dating from c. 500 BC, that shows a boy crouched on a rock with a fishing-rod in his right hand and a basket in his left. In the water below there is a rounded object of the same material with an opening on the top. This has been identified as a fish-cage used for keeping live fish, or as a fish-trap. It is clearly not a net. This object is currently in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[15]

In the 2nd century BC, the Greek Polybius's Histories describes hunting for swordfish by using a harpoon with a barbed and detachable head.[16]

Around AD 180, Oppian of Corycus composed a Greek didactic poem on Greco-Roman sea fishing, the Halieutica. This is the earliest such work to have survived intact to the modern day. Oppian describes various means of fishing including the use of nets cast from boats, scoop nets held open by a hoop, spears and tridents, and various traps "which work while their masters sleep". Oppian's description of fishing with a "motionless" net is also very interesting:

- The fishers set up very light nets of buoyant flax and wheel in a circle round about while they violently strike the surface of the sea with their oars and make a din with sweeping blow of poles. At the flashing of the swift oars and the noise the fish bound in terror and rush into the bosom of the net which stands at rest, thinking it to be a shelter: foolish fishes which, frightened by a noise, enter the gates of doom. Then the fishers on either side hasten with the ropes to draw the net ashore.

Pictorial evidence of Roman fishing comes from mosaics which show fishing from boats with rod and line as well as nets. Various species such as conger, lobster, sea urchin, octopus and cuttlefish are illustrated.[17] In a parody of fishing, a type of gladiator called retiarius was armed with a trident and a casting-net. He would fight against the murmillo, who carried a short sword and a helmet with the image of a fish on the front.

The Greco-Roman sea god Neptune is depicted as wielding a fishing trident.

In India, the Pandyas, a classical Dravidian Tamil kingdom, were known for the pearl fishery as early as the 1st century BC. Their seaport Tuticorin was known for deep sea pearl fishing. The paravas, a Tamil caste centred in Tuticorin, developed a rich community because of their pearl trade, navigation knowledge and fisheries.

In Norse mythology the sea giantess Rán uses a fishing net to trap lost sailors.

The Moche people of ancient Peru depicted fisherman in their ceramics.[18]

-

Poseidon/Neptune sculpture in Copenhagen Port.

-

.jpg)

Relief of fishermen collecting their catch from Mereruka’s tomb, 6th dynasty

-

Moche Fisherman. 300 A.D. Larco Museum Collection Lima, Peru.

-

Fisherman with net and trap in Germany, 1568.

Commercial fishing

-

Oyster harvesting using rakes (top) and sail driven dredges (bottom). From L'Encyclpédie of 1771

-

Oyster culture using tiles as culch. Taken from The Illustrated London News 1881

-

Department of Gironde (33) - Andernos-les-Bains, little boats of the oyster culturists (circa 1920)

Fish netting

Gillnets existed in ancient times as archaeological evidence from the Middle East demonstrates.[19] In North America, aboriginal fishermen used cedar canoes and natural fibre nets, e.g., made with nettels or the inner bark of cedar.[20] They would attach stones to the bottom of the nets as weights, and pieces of wood to the top, to use as floats. This allowed the net to suspend straight up and down in the water. Each net would be suspended either from shore or between two boats. Native fishers in the Pacific Northwest, Canada, and Alaska still commonly use gillnets in their fisheries for salmon and steelhead.

Both drift gillnets and setnets also have been widely adapted in cultures around the world. The antiquity of gillnet technology is documented by a number of sources from many countries and cultures. Japanese records trace fisheries exploitation, including gillnetting, for over 3,000 years. Many relevant details are available concerning the Edo period (1603–1867).[21] Fisheries in the Shetland Islands, which were settled by Norsemen during the Viking era, share cultural and technological similarities with Norwegian fisheries, including gillnet fisheries for herring.[22] Many of the Norwegian immigrant fishermen who came to fish in the great Columbia River salmon fishery during the second half of the 19th century did so because they had experience in the gillnet fishery for cod in the waters surrounding the Lofoten Islands of northern Norway.[23] Gillnets were used as part of the seasonal round by Swedish fishermen as well.[24] Welsh and English fishermen gillnetted for Atlantic salmon in the rivers of Wales and England in coracles, using hand-made nets, for at least several centuries.[25] These are but a few of the examples of historic gillnet fisheries around the world.

Gillnetting was an early fishing technology in Colonial America, used for example, in fisheries for Atlantic salmon and shad.[26] Immigrant fishermen from northern Europe and the Mediterranean brought a number of different adaptations of the technology from their respective homelands with them to the rapidly expanding salmon fisheries of the Columbia River from the 1860s forward.[27] The boats used by these fisherman were typically around 25 feet (8 m) long and powered by oars. Many of these boats also had small sails and were called "row-sail" boats. At the beginning of the 20th century, steam powered ships would haul these smaller boats to their fishing grounds and retrieve them at the end of each day. However, at this time gas powered boats were beginning to make their appearance, and by the 1930s, the row-sail boat had virtually disappeared, except in Bristol Bay, Alaska, where motors were prohibited in the gillnet fishery by territorial law until 1951.[28]

In 1931, the first powered drum was created by Laurie Jarelainen. The drum is a circular device that is set to the side of the boat and draws in the nets. The powered drum allowed the nets to be drawn in much faster and along with the faster gas powered boats, fisherman were able to fish in areas they had previously been unable to go into, thereby revolutionizing the fishing industry.

During World War II, navigation and communication devices, as well as many other forms of maritime equipment (ex. depth-sounding and radar) were improved and made more compact. These devices became much more accessible to the average fisherman, thus making their range and mobility increasingly larger. It also served to make the industry much more competitive, as the fisherman were forced to invest more into their boats and equipment in order to stay up to date with the current technology.

The introduction of fine synthetic fibres such as nylon in the construction of fishing gear during the 1960s marked an expansion in the commercial use of gillnets. The new materials were cheaper and easier to handle, lasted longer and required less mainatenance than natural fibres. In addition, fibres such as nylon monofilaments become almost invisible in water, so nets made with synthetic twines generally caught greater numbers of fish than natural fibre nets used in comparable situations.

Nylon is highly resistant to abrasion, hence the netting has the potential to last for many years if it is not recovered. This ghost fishing is of environmental concern, however it is difficult to generalise about the longevity of ghost-fishing gillnets due to the varying environments in which they are used. Some researchers have found gill-nets to be still catching fish and crustaceans for over a year after loss, while others have found lost nets to be destroyed by wave action within one month or overgrown with seaweeds, increasing their visibility and reducing their catching potential to such an extent that they became a microhabitat used by small fishes.

This type of net was heavily used by many Japanese, South Korean, and Taiwanese fishing fleets on the high seas in the 1980s to target tunas. Although highly selective with respect to size class of animals captured, gill nets are associated with high numbers of incidental captures of cetaceans, (whales and dolphins). In the Sri Lankan gill net fishery, one dolphin is caught for every 1.7-4.0 tonnes of tuna landed. This compares poorly with the rate of one dolphin per 70 tonnes of tuna landed in the eastern Pacific purse seine tuna fishery. Gillnets were banned by the United Nations in 1993 in international waters, although their use is still permitted within 200 nautical miles (400 km) of a coast.

Herring fisheries

-

Norse herring boat

-

The Dutch herring fleet, c. 1700.

-

The last surviving steam drifter of the Great Yarmouth herring fleet, Norfolk

-

Barrels for salted herring, c. 1465 at the archaeological site of Walraversijde, near Oostende, Belgium

-

A woman carrying herring to be sold at a market, Paris, ca 1500

-

Herring fishing in Scania, 1555

-

17th century herring factory in Amsterdam

-

Still life with herring and stoneware jug, Georg Flegel, c. 1600

-

Still life with a glass of beer and smoked herring on a plate. Pieter Claesz 1636.

-

Still Life with smoked herrings on yellow paper, Van Gogh 1889

-

Japanese Pacific herring fisherman's house in the historic village of Hokkaido, Sapporo

-

Making herring oil in the historic village

-

Salt Pans Bay, UK. Salt made in the pans in the 18th century was used to cure and pack herrings landed at local ports.

-

The Cooperage. Coopers once made wooden barrels to hold herrings in the courtyard behind these English cottages.

-

Herring fishery museum in Petershagen, Germany.

- ^ Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 9 January 1792.

Trawling

In the Middle Ages, Brixham was the largest fishing port in the South-West, and at one time it was the greatest in England. Brixham is also famous for being the town where the fishing trawler was invented in the 19th century. These elegant wooden boats were and all over the world, influencing fishing fleets everywhere. Their distinctive sails inspired the song Red Sails in the Sunset which was written aboard a Brixham sailing trawler called the Torbay Lass. Known as the "Mother of Deep-Sea Fisheries", its boats sailed all round the coasts and helped to establish the fishing industries of Hull, Grimsby and Lowestoft. In the 1890s there were about 300 trawling vessels here, each owned by one man who was often the skipper of his own boat.

One of the biggest ports in England for trawlers was Hull in Yorkshire on England's north-east coast.

The largest fishing port in Europe from the 1970s onwards has been Peterhead in the North-East corner of Scotland. In its prime in the 1980s Peterhead had over 500 trawlers staying at sea for a week each trip. Peterhead has seen a significant decline in the number of vessels and the value of fish landed has been reduced due to several decades of overfishing which in turn has reduced quotas.

Cod trade

One of the world’s longest lasting trade histories is the trade of dry cod from the Lofoten area to the southern parts of Europe, Italy, Spain and Portugal. The trade in cod started during the Viking period or before, has been going on for more than 1000 years and is still important.

Cod has been an important economic commodity in an international market since the Viking period (around 800 AD). Norwegians used dried cod during their travels and soon a dried cod market developed in southern Europe. This market has lasted for more than 1000 years, passing through periods of Black Death, wars and other crises and still is an important Norwegian fish trade.[29] The Portuguese have been fishing cod in the North Atlantic since the 15th century, and clipfish is widely eaten and appreciated in Portugal. The Basques also played an important role in the cod trade and are believed to have found the Canadian fishing banks in the 16th century. The North American east coast developed in part due to the vast amount of cod, and many cities in the New England area spawned near cod fishing grounds.

Apart from the long history this particular trade also differs from most other trade of fish by the location of the fishing grounds, far from large populations and without any domestic market. The large cod fisheries along the coast of North Norway (and in particular close to the Lofoten islands) have been developed almost uniquely for export, depending on sea transport of stockfish over large distances.[30] Since the introduction of salt, dried salt cod ('klippfisk' in Norwegian) has also been exported. The trade operations and the sea transport were by the end of the 14th century taken over by the Hanseatic League, Bergen being the most important port of trade.[31]

William Pitt the Elder, criticizing the Treaty of Paris in Parliament, claimed that cod was "British gold"; and that it was folly to restore Newfoundland fishing rights to the French.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the New World, especially in Massachusetts and Newfoundland, cod became a major commodity, forming trade networks and cross-cultural exchanges. In the 20th century, Iceland re-emerged as a fishing power and entered the Cod Wars to gain control over the north Atlantic seas. In the late 20th century and early 21st century, cod fishing off the coast of Europe and America severely depleted cod stocks there which has since become a major political issue as the necessity of restricting catches to allow fish populations to recover has run up against opposition from the fishing industry and politicians reluctant to approve any measures that will result in job losses. The 2006 Northwest Atlantic cod quota is set at 23,000 tons representing half the available stocks, while it is set to 473,000 tons for the Northeast Atlantic cod.

The Pacific Cod is currently enjoying a strong global demand. The 2006 TAC for the Gulf of Alaska and Berning Sea Aleutian Island was set at 574 million pounds (260,360 tons).

Trepanging

Trepanging is the collection or harvesting of sea cucumbers, also called "trepang". One who does this activity is called a trepanger.

To supply the markets of Southern China, Muslim trepangers from Makassar, Indonesia traded with the Indigenous Australians of Arnhem Land from the early 18th century or before. This Macassan contact with Australia is the first recorded example of interaction between the inhabitants of the Australian continent and their Asian neighbours.[32]

This contact had a major impact on the Indigenous Australians. The Macassans exchanged goods such as cloth, tobacco, knives, rice and alcohol for the right to trepang coastal waters and employ local labour. Macassan pidgin became a lingua franca along the north coast among different Indigenous Australian groups who were brought into greater contact with each other by the seafaring Macassan culture.[32]

Remains of Macassan trepang processing plants from the 18th and 19th centuries can still be found at Australian locations such as Port Essington and Groote Eylandt, along with stands of tamarind trees (which are native to Madagascar and East Africa) introduced by the seafaring Muslims.[32]

Chinese Americans

Countless experienced Chinese fishermen came from China's Pearl River Delta region to the California coast in the 1850s. They founded a fishing economy which grew exponentially, extending along the whole of the West Coast of the United States from Canada to Mexico by the 1880s. With entire fleets of small boats (sampans; 舢舨) the Chinese fishermen caught herring, soles, smelts, cod, sturgeon, and shark in the sea. To catch the larger fish like the barracudas, they used Chinese junks, which were built in large numbers on the American west coast. Among the yield caught by the Chinese American fishermen also included crabs, clams, abalone, salmon, and seaweed – all of which, including shark, formed the staple of Chinese cuisine. The produce were then sold in the local markets or shipped salt-dried for East Asia and Hawaii.[34]

Again this initial success was met with a hostile reaction. Since the late 1850s, European migrants – above all Greeks, Italians and Dalmatians – moved into fishing off the American west coast too, and they exerted pressure on the California legislature, which, finally, expelled the Chinese fishermen with a whole array of taxes, laws and regulations. They had to pay special taxes (Chinese Fisherman's Tax), and they were not allowed to fish with traditional Chinese nets nor with junks. The most disastrous effect occurred when the Scott Act, a federal US law adopted in 1888, established that the Chinese migrants, even when they had entered and were living the US legally, could not re-enter after having temporarily left US territory. The Chinese fishermen, in effect, could therefore not leave with their boats the 3-mile (4.8 km) zone of the west coast.[35] Their work became unprofitable, and gradually they gave up fishing. The only area where the Chinese fishermen remained unchallenged was shark fishing, where they stood in no competition to the European-Americans. Many former fishermen found work in the salmon canneries which until the 1930s were major employers of Chinese migrants, because white workers were barely interested in engaging in such hard, seasonal and relatively unrewarding activities.[36]

Artisan fishing

Recreational fishing

The earliest English essay on recreational fishing was published in 1496, shortly after the invention of the printing press. The authorship of this was attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, the prioress of the Benedictine Sopwell Nunnery. The essay was titled Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle, and was published in the second Boke of St Albans, a treatise on hawking, hunting and heraldry. These were major interests of the nobility, and the publisher, Wynkyn de Worde, was concerned that the book should be kept from those who were not gentlemen, since their immoderation in angling might "utterly destroye it".[37]

During the 16th century the work was much read, and was reprinted many times. Treatyse includes detailed information on fishing waters, the construction of rods and lines, and the use of natural baits and artificial flies. It also includes modern concerns about conservation and angler etiquette.[38]

-

Sketch of Juliana Berners

-

Izaak Walton

-

.jpg)

Angling for pike in the 17th century

-

Charles F. Holder with his then record 183 lb. bluefin tuna catch, 1898.

Recreational fishing for sport or leisure took off during the 16th and 17th centuries, and coincides with the publication of Izaak Walton's The Compleat Angler, or Contemplative Man's Recreation in 1653. This book is the definitive work that champions the position of the angler who loves fishing for the sake of fishing.[37]

More than 300 editions of The Compleat Angler have been published, which makes it one of the most frequently reprinted books in English literature. The pastoral discourse is enriched with country fishing folklore, songs and poems, recipes and anecdotes, moral meditations and quotes from classic literature. The central character, Piscator, champions the art of angling, but also tranquilly relishes the pleasures of friendship, verse and song, good food and drink.[39]

Big-game fishing started as a sport after the invention of the motorized boat. In 1898, Dr. Charles Frederick Holder, a marine biologist and early conservationist, virtually invented this sport and went on to publish many articles and books on the subject noted for their combination of accurate scientific detail with exciting narratives.

The fishing reel

In literary records, the earliest evidence of the fishing reel comes from a 4th-century AD[40][41] work entitled Lives of Famous Immortals.[42][43] The earliest known depiction of a fishing reel comes from a Southern Song (1127–1279) painting done in 1195 by Ma Yuan (c. 1160–1225) called "Angler on a Wintry Lake," showing a man sitting on a small sampan boat while casting out his fishing line.[44] Another fishing reel was featured in a painting by Wu Zhen (1280–1354).[44] The book Tianzhu lingqian (Holy Lections from Indian Sources), printed sometime between 1208 and 1224, features two different woodblock print illustrations of fishing reels being used.[44] An Armenian parchment Gospel of the 13th century shows a reel (though not as clearly depicted as the Chinese ones).[44] The Sancai Tuhui, a Chinese encyclopedia published in 1609, features the next known picture of a fishing reel and vividly shows the windlass pulley of the device.[44] These five pictures mentioned are the only ones which feature fishing reels before the year 1651 (when the first English illustration was made); after that year they became commonly depicted in world art.[44]

Fly fishing

Many credit the first recorded use of an artificial fly to the Roman Claudius Aelianus near the end of the 2nd century. He described the practice of Macedonian anglers on the Astraeus River:

- ...they have planned a snare for the fish, and get the better of them by their fisherman's craft. . . . They fasten red . . . wool round a hook, and fit on to the wool two feathers which grow under a cock's wattles, and which in colour are like wax. Their rod is six feet long, and their line is the same length. Then they throw their snare, and the fish, attracted and maddened by the colour, comes straight at it, thinking from the pretty sight to gain a dainty mouthful; when, however, it opens its jaws, it is caught by the hook, and enjoys a bitter repast, a captive.

In his book Fishing from the Earliest Times, however, William Radcliff (1921) gave the credit to Martial (Marcus Valerius Martialis), born some two hundred years before Aelian, who wrote:

- ...Who has not seen the scarus rise, decoyed and killed by fraudful flies...

The last word, somewhat indistinct in the original, is either "mosco" (moss) or "musca" (fly) but catching fish with fraudulent moss seems unlikely.

Japan

Tenkara fishing is a type of recreational fly-fishing that originated in Japan at least as long as 430 years ago,[45] when anglers discovered they could dress their flies with pieces of fabric and use those to fool the fish. The art became more refined as the samurai, who were forbidden to practice martial arts and sword fighting in the Edo period, found this type of fishing to be a good substitute for their training: the rod being a substitute to the sword, and walking on the rocks of a small stream good leg and balance training. "Only the samurai were permitted to do it [fish]. So, the samurai who enjoyed ayu fishing would take sewing needles and bend them themselves, and make their own flies by hand.".[45] Nowadays, these rods along with fishing flies, are considered to be a traditional local craft of the Kaga region.[46] The Meboso family in Kanazawa has been making these flies for as long as 400 years themselves, and are currently a 20-generation fly-tiers. [47]

United Kingdom

Modern western fly fishing is normally said to have originated on the fast, rocky rivers of Scotland and northern England. Other than a few fragmented references, however, little was written on fly fishing until The Treatyse on Fysshynge with an Angle was published (1496) within The Boke of St. Albans attributed to Dame Juliana Berners. The book contains, along with instructions on rod, line and hook making, dressings for different flies to use at different times of the year. The first detailed writing about the sport comes in two chapters of Izaak Walton's Compleat Angler, which were actually written by his friend Charles Cotton, and described the fishing in the Derbyshire Wye.

British fly-fishing continued to develop in the 19th century, with the emergence of fly fishing clubs, along with the appearance of several books on the subject of fly tying and fly fishing techniques. In southern England, dry-fly fishing acquired an elitist reputation as the only acceptable method of fishing the slower, clearer rivers of the south such as the River Test and the other 'chalk streams' concentrated in Hampshire, Surrey, Dorset and Berkshire (see Southern England Chalk Formation for the geological specifics). The weeds found in these rivers tend to grow very close to the surface, and it was felt necessary to develop new techniques that would keep the fly and the line on the surface of the stream. These became the foundation of all later dry-fly developments. However, there was nothing to prevent the successful employment of wet flies on these chalk streams, as George E.M. Skues proved with his nymph and wet fly techniques. To the horror of dry-fly purists, Skues later wrote two books, Minor Tactics of the Chalk Stream, and The Way of a Trout with the Fly, which greatly influenced the development of wet fly fishing. In northern England and Scotland, many anglers also favored wet-fly fishing, where the technique was more popular and widely practised than in southern England. One of Scotland’s leading proponents of the wet fly in the early-to-mid-19th century was W.C. Stewart, who published "The Practical Angler" in 1857.

Scandinavia

In Scandinavia and the United States, attitudes toward methods of fly fishing were not nearly as rigidly defined, and both dry- and wet-fly fishing were soon adapted to the conditions of those countries.

Lines made of silk replaced those of horse hair and were heavy enough to be cast in the modern style. Cotton and his predecessors fished their flies with long rods, and light lines allowing the wind to do most of the work of getting the fly to the fish. The introduction of new woods to the manufacture of fly rods, first greenheart and then bamboo, made it possible to cast flies into the wind on silk lines. These early fly lines proved troublesome as they had to be coated with various dressings to make them float and needed to be taken off the reel and dried every four hours or so to prevent them from becoming waterlogged.

United States

Americans rod builders such as Hiram Leonard developed superior techniques for making bamboo rods: thin strips were cut from the cane, milled into shape, and then glued together to form light, strong, hexagonal rods with a solid core that were superior to anything that preceded them.

Fly reels were soon improved, as well. At first they were rather mechanically simple; more or less a storage place for the fly line and backing. In order to tire the fish, anglers simply applied hand pressure to the rim of the revolving spool, known as 'palming' the rim – see fishing reel. In fact, many superb modern reels still use this simple design.

In the United States, fly fishermen are thought to be the first anglers to have used artificial lures for bass fishing. After pressing into service the fly patterns and tackle designed for trout and salmon to catch largemouth and smallmouth bass, they began to adapt these patterns into specific bass flies. Fly fishermen seeking bass developed the spinner/fly lure and bass popper fly, which are still used today.[48]

In the late 19th century, American anglers, such as Theodore Gordon, in the Catskill Mountains of New York began using fly tackle to fish the region’s many brook trout-rich streams such as the Beaverkill and Willowemoc Creek. Many of these early American fly fishermen also developed new fly patterns and wrote extensively about their sport, increasing the popularity of fly fishing in the region and in the United States as a whole.[48] The Junction Pool in Roscoe, where the Willowemoc flows into the Beaver Kill, is the center of an almost ritual pilgrimage every April 1, when the season begins. Albert Bigelow Paine, a New England author, wrote about fly fishing in The Tent Dwellers, a book about a three week trip he and a friend took to central Nova Scotia in 1908.

Participation in fly fishing peaked in the early 1920s in the eastern states of Maine and Vermont and in the Midwest in the spring creeks of Wisconsin. Along with deep sea fishing, Ernest Hemingway did much to popularize fly fishing through his works of fiction, including The Sun Also Rises. It was the development of inexpensive fiberglass rods, synthetic fly lines, and monofilament leaders, however, in the early 1950s, that revived the popularity of fly fishing, especially in the United States.

In recent years, interest in fly fishing has surged as baby boomers have discovered the sport. Movies such as Robert Redford's film A River Runs Through It, starring Brad Pitt, cable fishing shows, and the emergence of a competitive fly casting circuit have also added to the sport's visibility.

Fishing in art

-

Engraving of Russian peasant children fishing, A.P. Koverznev 1875

-

Fishing, Almeida Júnior 1894

-

Fishing from a canoe, Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

-

Fishing with a harpoon, Adolph Tidemand 1851

-

The fishing fleet at Reine, Gunnar Berg (1863–93)

-

The Chinese fishing nets of Fort Cochin," from 'Das Buch der Welt', Stuttgart, 1842–48

See also

- History of seafood

- History of whaling

- US bluefin tuna industry

Notes

- ↑ Fisheries and Aquaculture in our Changing Climate Policy brief of the FAO for the UNFCCC COP-15 in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- ↑ FAO: Fisheries and Aquaculture

- ↑ African Bone Tools Dispute Key Idea About Human Evolution National Geographic News article.

- ↑ Early humans followed the coast BBC News article.

- ↑ Yaowu Hu Y, Hong Shang H, Haowen Tong H, Olaf Nehlich O, Wu Liu W, Zhao C, Yu J, Wang C, Trinkaus E and Richards M (2009) "Stable isotope dietary analysis of the Tianyuan 1 early modern human" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106 (27) 10971-10974.

- ↑ First direct evidence of substantial fish consumption by early modern humans in China PhysOrg.com, 6 July 2009.

- ↑ Coastal Shell Middens and Agricultural Origasims in Atlantic Europe.

- ↑ Guthrie, Dale Guthrie (2005) The Nature of Paleolithic Art. Page 298. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31126-0

- ↑ King 1991, pp. 80-81.

- ↑ Rostlund 1952, pp. 188-190

- ↑ Ray 2003, page 93

- ↑ Allchin 1975, page 106

- ↑ Edgerton 2003, page 74

- ↑ Fisheries history: Gift of the Nile PDF.

- ↑ Image of an ancient angler on a wine cup.

- ↑ Polybius, "Fishing for Swordfish", Histories Book 34.3 (Evelyn S. Shuckburgh, translator). London, New York: Macmillan, 1889. Reprint Bloomington, 1962.

- ↑ Image of fishing illustrated in a Roman mosaic.

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ Nun, Mendel (1989). The Sea of Galilee and Its Fishermen in the New Testament, pp. 28-44. Kibbutz Ein Gev, Kinnereth Sailing Co.

- ↑ Stewart, Hilary (1994). Indian Fishing: Early Methods on the Northwest Coast. Seattle, University of Washington Press.

- ↑ Ruddle, Kenneth and Akimich, Tomoya. “Sea Tenure in Japan and the Southwestern Ryukyus,” in Cordell, John, Ed. (1989), A Sea of Small Boats, pp. 337-370. Cambridge, Mass., Cultural Survival, Inc.

- ↑ Goodlad, C.A. (1970). Shetland Fishing Saga, pp. 59-60. The Shetland Times, Ltd.

- ↑ Martin, Irene (1994). Legacy and Testament: The Story of the Columbia River Gillnetter, p. 38. Pullman, Washington State University Press.

- ↑ Lofgen, Ovar. “Marine Ecotypes in Preindustrial Sweden: A Comparative Discussion of Swedish Peasant Fishermen,” in Andersen, Raoul, ed., North Atlantic Maritime Cultures, pp. 83-109. The Hague, Mouton.

- ↑ Jenkins, J. Geraint (1974). Nets and Coracles, p. 68. London, David and Charles.

- ↑ Netboy, Anthony (1973) The Salmon: Their Fight for Survival, pp. 181-182. Boston, Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ Martin, 1994, p. 44.

- ↑ Andrews, Ralph W. and Larsen, A.K. (1959). Fish and Ships, p. 108. Seattle, Superior Publishing Co.

- ↑ James Barrett, Roelf Beukens, Ian Simpson, Patrick Ashmore, Sandra Poaps and Jacqui Huntley (2000). "What Was the Viking Age and When did it Happen? A View from Orkney.". Norwegian Archaeological Review 33 (1).

- ↑ G. Rollefsen (1966). "Norwegian fisheries research". Fiskeridirektoratets Skrifter, Serie Havundersøkelser 14 (1): 1–36.

- ↑ A. Holt-Jensen (1985). "Norway and sea the shifting importance of marine resources through Norwegian history.". GeoJournal 10 (4).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 MacKnight, CC (1976). The Voyage to Marege: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia. Melbourne University Press.

- ↑ "Chinese Fishermen, Monterey, California. 1875": From Monterey County Photographs: Chinese Fishing Village Images. California Historical Society. The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ Brownstone, p.74; McCunn, p.44

- ↑ Cassel, p.435

- ↑ Vessels of Exchange: the Global Shipwright in the Pacific, Hans Konrad Van Tilburg, University of Hawaiêi at Manoa; Brownstone, p.74; McCunn, p.47

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Cowx, I G (2002) Handbook of Fish Biology and Fisheries, Chapter 17: Recreational fishing. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-632-06482-X

- ↑ Berners, Dame Juliana. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 20, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ↑ Walton, Izaak. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 20, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ↑ Birrell (1993), 185.

- ↑ Hucker (1975), 206.

- ↑ Ronan (1994), 41.

- ↑ Temple (1986), 88.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 2, 100 & PLATE CXLVII.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 http://make.pingmag.jp/2008/05/06/hachirobe/

- ↑ http://shofu.pref.ishikawa.jp/

- ↑ Kaga Kebari Feather Bait. Experience Kanazawa. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Waterman, Charles F., Black Bass and the Fly Rod, Stackpole Books (1993)

References

- Bekker-Nielson (2002) "Fish in the ancient economy" In: Skydsgaard JE and Ascani K (Eds.) Ancient history matters: Studies presented to Jens Erik Skydsgaard on his seventieth birthday, L'erma di Bretschneider. Pages 29–38. ISBN 978-88-8265-190-9

- Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes (2005) Ancient fishing and fish processing in the Black Sea region Aarhus University Press. ISBN 9788779340961.

- King, Chester D (1991). Evolution of Chumash Society: A Comparative Study of Artifacts Used for Social System Maintenance in the Santa Barbara Channel Region before A.D. 1804. New York and London, Garland Press.

- Lytle, Ephraim (2006) Marine Fisheries and the Ancient Greek Economy, ProQuest. ISBN 9780542816024.

- Pieters M, Verhaeghe F, Gevaert G, Mees J and Seys J. (Ed.) (2003) Colloquium: Fishery, trade and piracy: fishermen and fishermen's settlements in and around the North Sea area in the Middle Ages and later Museum Walraversijde, VLIZ Special Publication 15.

- Rostlund, Erhard (1952). Freshwater Fish and Fishing in Native North America. University of California Publications in Geography, Volume 9. Berkeley.

- Sahrhage, Dietrich and Lundbeck, Johannes (1992) A History of Fishing. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-55332-0

- Smith, Tim D (2002). Handbook of Fish Biology and Fisheries, Chapter 4, A history of fisheries and their science. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-632-06482-X

- Sicking L and Abreu-Ferreira D (Eds.) (2009) Beyond the catch: fisheries of the North Atlantic, the North Sea and the Baltic, 900-1850 Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16973-9.

- Starkey, David J.; Jon Th. Thor & Ingo Heidbrink (Eds.): A History of the North Atlantic Fisheries: Vol. 1, From Early Times to the mid-Nineteenth Century. Bremen (Hauschild Vlg. & Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum) 2009.

External links

- Roman fishing

- Medieval Origins of Commercial Sea Fishing Project

- Fishing & Fishermen in the Middle Ages and Renaissance

- The Shoals of Herring sung by Ewan MacColl with historic images of herring fishing in Great Yarmouth – YouTube

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||