History of Xinjiang

The recorded history of the area now known as Xinjiang dates to the 2nd millennium BC. There have been many empires, primarily Han Chinese, Turkic, and Mongolic, that have ruled over the region, including the Yuezhi, Xiongnu Empire, Han Dynasty, Sixteen Kingdoms of the Jin Dynasty (Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, and Western Liáng), Tang Dynasty, Uyghur Khaganate, Kara-Khanid Khanate, Mongol Empire (Yuan Dynasty), Yarkent Khanate, Mongolic Dzungar Khanate, and Manchu Qing Dynasty. Xinjiang was previously known as "Xiyu" (西域), under the Han Dynasty, which drove the Xiongnu empire out of the region in 60 BCE in an effort to secure the profitable Silk Road,[1] but was renamed Xinjiang (新疆, meaning "new frontier") when the region was reconquered by the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty in 1759. Xinjiang is now a part of the People's Republic of China, having been so since its founding year of 1949.

Background

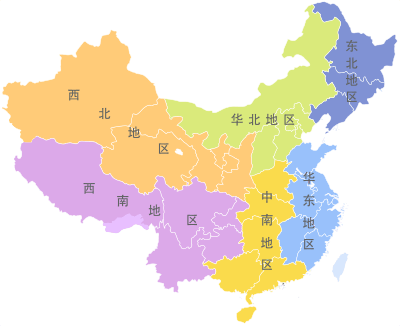

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names, Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains, before Qing China unified them into one political entity called Xinjiang province in 1884. At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Oirat Mongol Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghur people. They were governed separately until 1884. The native Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin is Altishahr.

The Qing dynasty was well aware of the differences between the former Buddhist Mongol area to the north of the Tianshan and Turkic Muslim south of the Tianshan, and ruled them in separate administrative units at first.[2] However, Qing people began to think of both areas as part of one distinct region called Xinjiang .[3] The very concept of Xinjiang as one distinct geographic identity was created by the Qing and it was originally not the native inhabitants who viewed it that way, but rather it was the Chinese who held that point of view.[4] During the Qing rule, no sense of "regional identity" was held by ordinary Xinjiang people; rather, Xinjiang's distinct identity was given to the region by the Qing, since it had distinct geography, history and culture, while at the same time it was created by the Chinese, multicultural, settled by Han and Hui, and separated from Central Asia for over a century and a half.[5]

In the late 19th century, it was still being proposed by some people that two separate parts be created out of Xinjiang, the area north of the Tianshan and the area south of the Tianshan, while it was being argued over whether to turn Xinjiang into a province.[6]

In ancient China, the area was known as "Xiyu" or "Western Regions", a name that became prevalent in Chinese records after the Han Dynasty took control of the region.[1][7] For the Uyghurs, the traditional name of the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang was Altishahr, which means "six cities" in the Uyghur language. The region of Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang was named after its native inhabitants, the Dzungar Mongols.

The name "East Turkestan" was created by the Russian Sinologist Nikita Bichurin to replace the term "Chinese Turkestan" in 1829.[8] "East Turkestan" was used traditionally to only refer to the Tarim Basin, and not Xinjiang as a whole, with Dzungaria being excluded from the area consisting of "East Turkestan".

After the Qing Dynasty reconquered this region in 1884, the area was designated Xinjiang, which was used to refer to any area of former a Chinese empire that had been previously lost but was regained by the Qing, but eventually meant this northwestern Xinjiang alone.[9] In the Uyghur language, Xinjiang is considered more center than northwestern in orientation.[10]

Early Caucasian Inhabitants

According to J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair, the Chinese describe the existence of "white people with long hair" or the Bai people in the Shan Hai Jing, who lived beyond their northwestern border.[11]

The well preserved Tarim mummies with Caucasoid features, often with reddish or blond hair, today displayed at the Ürümqi Museum and dated to the 2nd millennium BC, have been found in the same area of the Tarim Basin. Various nomadic tribes, such as the Yuezhi were probably part of the migration of Indo-European speakers who were settled in eastern Central Asia (possibly as far as Gansu) at that time. The Ordos culture in northern China east of the Yuezhi, is another example, yet skeletal remains from the Ordos culture found have been predominantly Mongoloid.

Chinese accounts

The first reference to the nomadic Yuezhi was in 645 BC by Guan Zhong in his Guanzi 管子 (Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yuzhi 禺氏, or Niuzhi 牛氏, as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains of Yuzhi 禺氏 at Gansu.[12] The supply of jade from the Tarim Basin[13] from ancient times is well documented archaeologically: "It is well known that ancient Chinese rulers had a strong attachment to jade. All of the jade items excavated from the tomb of Fuhao of the Shang dynasty, more than 750 pieces, were from Khotan in modern Xinjiang. As early as the mid-first millennium BC the Yuezhi engaged in the jade trade, of which the major consumers were the rulers of agricultural China." (Liu (2001), pp. 267–268).

The nomadic tribes of the Yuezhi are documented in Chinese historical accounts, in particular the 2nd-1st century BC "Records of the Great Historian", or Shiji, by Sima Qian. According to these accounts:

- "The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly Mountains (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang, but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan, where they attacked and conquered the people of Daxia and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui [= Oxus] River. A small number of their people who were unable to make the journey west sought refuge among the Qiang barbarians in the Southern Mountains, where they are known as the Lesser Yuezhi."[14]

According to Han accounts, the Yuezhi "were flourishing" during the time of the first great Chinese Qin emperor, but were regularly in conflict with the neighbouring tribe of the Xiongnu to the northeast.

Roman accounts

Pliny the Elder (, Chap XXIV "Taprobane") reports a curious description of the Seres (in the territories of northwestern China) made by an embassy from Taprobane (Ceylon) to Emperor Claudius, saying that they "exceeded the ordinary human height, had flaxen hair, and blue eyes, and made an uncouth sort of noise by way of talking", suggesting they may be referring to the ancient Caucasian populations of the Tarim Basin.

Genetic evidence

Modern genetic analysis suggests that aboriginal inhabitants had a high proportion of DNA of European origin.[15]

In 2009, the remains of individuals found at the Xiaohe Tomb complex were analyzed for Y-DNA and mtDNA markers. The study found that while Y-DNA corresponded to West Eurasian populations, the mtDNA haplotypes were an admixture of East Asian and European origin.[16] The geographic location of where this admixing took place is suggested to be somewhere in Southern Siberia before these people moved into the Tarim Basin. Xiaohe is the oldest archaeological site yielding human remains discovered in the Tarim Basin to date.

Some Uyghur scholars claim modern Uyghurs descent from both the Turkic Uyghurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (Yuezhi), and relatively fair hair and eyes, as well as other so-called 'Caucasoid' physical traits, are not uncommon among Uyghurs. Genetic analyses suggest West Eurasian ("Caucasoid") maternal contribution to Uyghurs is 42.6%. The estimation of European component in modern Uyghur population ranged from 30 to 60%.[17]

Struggle between Xiongnu and Han China

.png)

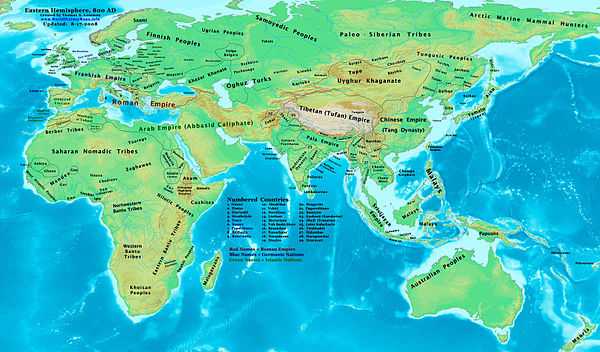

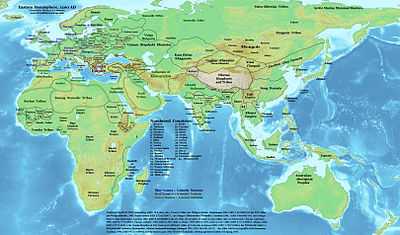

Traversed by the Northern Silk Road,[18] Western Regions is the Chinese name for the Tarim and Dzungaria regions of what is now northwest China. At the beginning of the Han Dynasty (206 BC - AD 220), the region was subservient to the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic people based in modern Mongolia. In the 2nd century BC, The Han Dynasty made preparations for war when the Emperor Wu of Han dispatched the explorer Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. As a result of these battles, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They succeeded in separating the Xiongnu from the Qiang peoples to the south, and also gained direct access to the Western Regions. Han China sent Zhang Qian as an envoy to the states in the region, beginning several decades of struggle between the Xiongnu and Han China over dominance of the region, eventually ending in Chinese success. In 60 BC Han China established the Protectorate of the Western Regions (西域都護府) at Wulei (烏壘; near modern Luntai) to oversee the entire region as far west as the Pamir. This became the first sign of Han Chinese rule in Central Asia, the sovereignty of Han dynasty expanded into Central Asia. Tarim Basin and Indo-European kingdoms was under the control of Han dynasty and was influenced by Han Chinese emperors.

During the usurpation of Wang Mang in China, the dependent states of the protectorate rebelled and returned to Xiongnu domination in AD 13. Over the next century, Han China conducted several expeditions into the region, re-establishing the protectorate from 74-76, 91-107, and from 123 onward. After the fall of the Han Dynasty (220), the protectorate continued to be maintained by Cao Wei (until 265) and the Western Jin Dynasty (from 265 onwards).

Uyghur nationalist historians such as Turghun Almas claim that Uyghurs were distinct and independent from Chinese for 6000 years, and that all non-Uyghur peoples are non-indigenous immigrants to Xinjiang.[19] However, the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) established military colonies (tuntian) and commanderies (duhufu) to control Xinjiang from 120 BCE, while the Tang Dynasty (618-907) also controlled much of Xinjiang until the An Lushan rebellion.[20] Chinese historians refute Uyghur nationalist claims by pointing out the 2000-year history of Han settlement in Xinjiang, documenting the history of Mongol, Kazakh, Uzbek, Manchu, Hui, Xibo indigenes in Xinjiang, and by emphasizing the relatively late "westward migration" of the Huigu (equated with "Uyghur" by the PRC government) people from Mongolia the 9th century.[19] The name "Uyghur" was associated with a Buddhist people in the Tarim Basin in the 9th century, but completely disappeared by the 15th century, until it was revived by the Soviet Union in the 20th century.[21]

A succession of peoples

The Western Jin Dynasty succumbed to successive waves of invasions by nomads from the north at the beginning of the 4th century. The short-lived non-Han Chinese kingdoms that ruled northwestern China one after the other, including Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, and Western Liáng, all attempted to maintain the protectorate, with varying extents and degrees of success. After the final reunification of northern China under the Northern Wei empire, its protectorate controlled what is now the southeastern third of Xinjiang. Local states such as Kashgar (Shule), Hotan (Yutian), Kucha (Guizi) and Cherchen (Qiemo) controlled the western half, while the central region around Turpan was controlled by Qara-hoja (Gaochang), remnants of a Xiongnu state Northern Liang that once ruled part of what is now Gansu province in northwestern China.

Gokturk Empire

In the late 5th century the Tuyuhun and the Rouran asserted power in southern and northern Xinjiang, respectively, and the Chinese protectorate was lost again. In the 6th century the Turks began to emerge in the Altay region, subservient to the Rouran. Within a century they had defeated the Rouran and established a vast Turkic Khaganate, stretching over most of Central Asia past both the Aral Sea in the west and Lake Baikal in the east. In 583 the Gokturks split into western and eastern halves, with Xinjiang coming under the western half. In 609, China under the Sui Dynasty defeated the Tuyuhun, forced him to take refuge in Qilian mountains.

Tang Dynasty

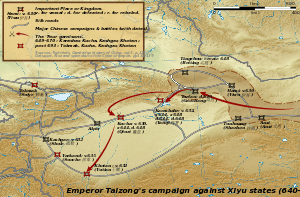

Starting from the 620's and 630's, Chinese Tang empire conducted a series of expeditions against the Eastern Turks.[22] By 640, military campaigns were dispatched against the Western Turkic Khaganate, and their vassals, the oasis states of southern Xinjiang.[23] The campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[24] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[25]

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who dispatched an army in 657 led by Su Dingfang against the Western Turk qaghan Ashina Helu. Ashina's defeat strengthened Tang rule in southern Xinjiang and brought the regions formerly controlled by the khaganate into the Tang empire.[25] The military expedition included 10,000 horsemen supplied by the Uyghurs, who were close allies of the Tang.[25] The Uyghurs had allied with the Tang ever since the dynasty supported their revolt against the reign of the Xueyantuo, a tribe of Tiele people.[26] Xinjiang was administered through the Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府; "Protectorate Pacifying the West") and the Four Garrisons of Anxi.

Tang hegemony beyond the Pamir Mountains in modern Tajikistan and Afghanistan ended with revolts by the Turks, but the Tang retained a military presence in Xinjiang. These holdings were later invaded by the Tibetan Empire to the south, and Xinjiang alternated between Tang and Tibetan rule as they competed for control of Central Asia.[27] In 662 a rebellion broke out and Tang army was sent to control the situation, but was badly defeated by the Tibetans in the south of Kashgar. After defeating Tang in 670, the Tibetans gained control of the whole region and completely subjugated Kashgar in 676-8 and retained possession until 692, then China regained control of all southern Xinjiang, and retained it for the next fifty years. 728, the local king of Kashgar was awarded a brevet by the Tang emperor. During the devastating Anshi Rebellion, Tibetans invaded Tang China on a wide front from Xinjiang to Yunnan, sacking the Tang capital in 763, and taking control of southern Xinjiang. At the same time, the Uyghur Empire took control of northern Xinjiang, as well as much of Central Asia, including Outer Mongolia where the Uyghur empire originated.

A significant milestone of the Tang period of Xinjiang was that it marked the end of Indo-European influence in Xinjiang.[24] This was partially spurred by Chinese policies, which unintentionally sped the turkification of Xinjiang,[27] rather than the sinification that had occurred in other territories conquered by the Tang.[28] The Tang Dynasty recruited a large number of Turkic soldiers and generals, and the Chinese garrisons of Xinjiang were for the most part staffed by Turks rather than those of the Han ethnicity. Xinjiang was beginning its transition into a region that is linguistically and culturally Turko-Mongolic, which it still is to this day.[27]

Uyghur Empire and Tang Dynasty

By 745 the Uyghur Empire stretched from the Caspian Sea to present-day Mongolia and lasted from 745 to 840. After the Battle of Talas in 751, Uyghur Khaganate took control of northern Xinjiang, as well as much of Central Asia, including Outer Mongolia, where their empire originated. It was also during this time that Tang China started a process of withdrawal from Central Asia. Bayanchur Khan acted quickly and took over the fertile Tarim Basin as well.[29]

The Chinese defeat at the Battle of Talas combined with a series of rebellions, the largest being of An Lushan, forced the Chinese emperor to turn to Bayanchur Khan for assistance. Seeing this as an ideal opportunity to meddle in Chinese affairs, the Khagan agreed, quelling several rebellions and defeating an invading Tibetan army from the south. As a result, the Uyghurs received tribute from the Chinese and Bayanchur Khan was given the daughter of the Chinese Emperor to marry (princess Ningo).

In 762, in alliance with the Tang, Tengri Bögü (Chinese transcription Idigan ) launched a campaign against the Tibetans. He recaptured for the Tang Emperor the western capital Luoyang. Khagan Tengri Bögü met with Manichaean priests from Iran while on campaign, and was converted to Manicheism, adopting it as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire.

In 779 Tengri Bögü, incited by sogdian traders, living in Ordu Baliq, planned an invasion of China to take advantage of the accession of a new emperor. Tengri Bögü's uncle, Tun Bagha Tarkhan opposed this plan, fearing it would result in Uyghur assimilation into Chinese culture.

In 840, the Kyrgyz tribe invaded from the north with a force of around 80,000 horsemen. They sacked the Uyghur capital at Ordu Baliq, razing it to the ground. The Kyrgyz captured the Uyghur Khagan, Kürebir (Hesa) and promptly beheaded him. The Kyrgyz went on to destroy other Uyghur cities throughout their empire, burning them to the ground. The last legitimate khagan, Öge, was assassinated in 847, having spent his 6-year reign in fighting the Kyrgyz and the supporters of his rival Ormïzt, a brother of Kürebir. The Kyrgyz invasion destroyed the Uyghur Empire, causing a diaspora of Uyghur people across Central Asia.

Uyghur State and Kara-Khanid Khanate

Both Tibet and the Uyghur Khaganate declined in the mid-9th century. After the Uyghur Khanate in Mongolia had been smashed by the Kirghiz in 840, branches of the Uyghurs established themselves in Qocha (Karakhoja) and Beshbalik near today's Turfan and Urumchi. This Uyghur Kara-Khoja Kingdom would remain in eastern Xinjiang until the 14th century, though it would be subject to various overlords during that time.

The Kara-Khanid Khanate arose some time in the ninth century from a confederation of Turkic tribes living in Semirechye, Western Tian Shan (modern Kyrgyzstan), and Western Xinjiang (Kashgaria).[30] They later occupied Transoxania. The Karakhanids were made up mainly of the Karluks, Chigils and Yaghma tribes. The capital of Karakhanid Khanate was Balasaghun on the Chu River, later also Samarkand and Kashgar. The Kara-Khanids converted to Islam, whereas the Uyghur state in eastern Xinjiang remained Manicheaean, but later converted to Buddhism. Nestorian Christianity was also a prominent faith in their kingdom.

Kara-Khitan Khanate

In 1132, remnants of the Khitan Empire from Manchuria entered Xinjiang, fleeing the onslaught of the Jurchens into north China. They established an exile regime, the Kara-Khitan Khanate, which became overlord over both Kara-Khanid-held and Uyghur State-held parts of the Tarim Basin for the next century.

Chagatai Khanate

After Genghis Khan had unified Mongolia and began his advance west, the Uyghur state in the Turfan-Urumchi area offered its allegiance to the Mongols in 1209, contributing taxes and troops to the Mongol imperial effort and worked as civil servants to the Mongols. In return, the Uyghur rulers retained control of their kingdom. In 1218, Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire captured what was once Kara-Khitan's territories. After the break-up of the Mongol Empire into smaller khanates, Xinjiang, though mostly ruled by the Chagatai Khanate, one of the successor states of the empire, in fact was fought over by Yuan Dynasty, the successor regime based in Mongolia and in China.

Moghulistan

After the death of Qazan Khan in 1346, the Chagatai Khanate, which embraced both East and West Turkestan, was divided into western (Transoxiana) and eastern (Moghulistan) halves. Power in the western half devolved into the hands of several tribal leaders, most notably the Qara'unas. Khans appointed by the tribal rulers were mere puppets. In the east, Tughlugh Timur (1347–1363), an obscure Chaghataite adventurer, gained ascendancy over the nomadic Mongols, and converted to Islam. During his rein (and ruled until 1363), the moghuls were converted to Islam and slowly turkizised. In 1360, and again in 1361, he invaded the western half in the hope that he could reunify the khanate. At their height, the Chaghataite domains extended from the Irtysh River in Siberia down to Ghazni in Afghanistan, and from Transoxiana to the Tarim Basin.

Moghulistan embraced settled lands in Eastern Turkestan as well as nomad lands north of Tangri Tagh. The settled lands were known at the time as Manglai Sobe or Mangalai Suyah, which translates as Shiny Land, or Advanced Land Which Faced the Sun. These lands included west and central Tarim oasis-cities, such as Khotan, Yarkand, Yangihisar, Kashgar, Aksu, and Uch Turpan; and hardly involved eastern Tangri Tagh oasis-cities, such as Kucha, Karashahr, Turpan and Kumul, where a local uyghur administration and buddhist population still existed. The nomadic areas comprised the present Kyrghyzstan and part of Kazakhstan, including Jettisu, the area of seven rivers.

Moghulistan existed around 100 years, and then split into two parts: Yarkand state (mamlakati Yarkand), with its capital at Yarkand, which embraced all the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan, and nomad Moghulistan, which embraced the nomad lands north of Tengri Tagh. The founder of Yarkand was Mirza Abu-Bakr, who was from the dughlat tribe. In 1465, he raised a rebellion, captured Yarkand, Kashgar, and Khotan, and declared himself an independent ruler, successfully repelling attacks by the Moghulistan rulers Yunus Khan and his son Akhmad Khan, or Ahmad Alaq, named Alach, "Slaughterer", for his war against the kalmyks.

Dughlat amirs had ruled the country that lay south of the Tarim Basin from the middle of the thirteenth century, on behalf of Chagatai Khan and his descendents, as their satellites. The first dughlat ruler, who received lands directly from the hands of Chagatai, was amir Babdagan or Tarkhan. The capital of the emirate was Kashgar, and the country was known as Mamlakati Kashgar. Although the emirate, representing the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan, was formally under the rule of the moghul khans, the dughlat amirs often tried to put an end to that dependence, and raised frequent rebellions, one of which resulted in the separation of Kashgar from Moghulistan for almost 15 years (1416–1435). Mirza Abu-Bakr ruled Yarkand for 48 years.[31]

State of Yarkand

In May, 1514, Sultan Said Khan, grandson of Yunus Khan (ruler of Moghulistan between 1462 and 1487) and third son of Akhmad Khan, made an expedition against Kashgar from Andijan with only 5000 men, and having captured the Yangihisar citadel, that defended Kashgar from south road, took the city, dethroning Mirza Abu-Bakr. Soon after, other cities of Eastern Turkestan — Yarkant, Khotan, Aksu, and Uch Turpan — joined him, and recognized Sultan Said Khan as ruler, creating a union of six cities, called Altishahr. Sultan Said Khan's sudden success is considered to be contributed to by the dissatisfaction of the population with the tyrannical rule of Mirza Abu-Bakr and the unwillingness of the dughlat amirs to fight against a descendant of Chagatai Khan, deciding instead to bring the head of the slain ruler to Sultan Said Khan. This move put an end to almost 300 years of rule (nominal and actual) by the Dughlat Amirs in the cities of West Kashgaria (1219–1514). He made Yarkand the capital of a state, "Mamlakati Yarkand" which lasted until 1678.

The Khojah Kingdom

In the 17th century, the Dzungars (Oirats, Kalmyks) established an empire over much of the region. Oirats controlled an area known as Grand Tartary or the Kalmyk Empire to Westerners, which stretched from the Great Wall of China to the Don River, and from the Himalayas to Siberia. A Sufi master Khoja Āfāq defeated Saidiye kingdom and took the throne at Kashgar with the help of the Oirat (Dzungar) Mongols. After Āfāq's death, the Dzungars held his descendants hostage. The Khoja dynasty rule in the Altishahr (Tarim Basin) region lasted until 1759.

Zunghar Empire

The Mongolian Dzungar (also Jungar, Zunghar or Zungar; Mongolian: Зүүнгар Züüngar) was the collective identity of several Oirat tribes that formed and maintained one of the last nomadic empires. The Dzungar Khanate covered the area called Dzungaria and stretched from the west end of the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan, and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia. Most of this area was only renamed "Xinjiang" by the Chinese after the fall of the Dzungar Empire. It existed from the early 17th century to the mid-18th century.

The Turkic Muslim sedentary people of the Tarim Basin were originally ruled by the Chagatai Khanate while the nomadic Buddhist Oirat Mongol in Dzungaria ruled over the Dzungar Khanate. The Naqshbandi Sufi Khojas, descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, had replaced the Chagatayid Khans as the ruling authority of the Tarim Basin in the early 17th century. There was a struggle between two factions of Khojas, the Afaqi (White Mountain) faction and the Ishaqi (Black Mountain) faction. The Ishaqi defeated the Afaqi, which resulted in the Afaqi Khoja inviting the 5th Dalai Lama, the leader of the Tibetan Buddhists, to intervene on his behalf in 1677. The 5th Dalai Lama then called upon his Dzungar Buddhist followers in the Zunghar Khanate to act on this invitation. The Dzungar Khanate then conquered the Tarim Basin in 1680, setting up the Afaqi Khoja as their puppet ruler.

Khoja Afaq asked the 5th Dalai Lama when he fled to Lhasa to help his Afaqi faction take control of the Tarim Basin (Kashgaria).[32] The Dzungar leader Galdan was then asked by the Dalai Lama to restore Khoja Afaq as ruler of Kashgararia.[33] Khoja Afaq collaborated with Galdan's Dzungars when the Dzungars conquered the Tarim Basin from 1678-1680 and set up the Afaqi Khojas as puppet client rulers. [34][35][36] The Dalai Lama blessed Galdan's conquest of the Tarim Basin and Turfan Basin.[37]

67,000 patman (each patman is 4 piculs and 5 pecks) of grain 48,000 silver ounces were forced to be paid yearly by Kashgar to the Dzungars and cash was also paid by the rest of the cities to the Dzungars. Trade, milling, and distilling taxes, corvée labor,saffron, cotton, and grain were also extracted by the Dzungars from the Tarim Basin. Every harvest season, women and food had to be provided to Dzungars when they came to extract the taxes from them.[38]

The Qing Empire

The Turkic Muslims of the Turfan and Kumul Oases then submitted to the Qing dynasty of China, and asked China to free them from the Dzungars. The Qing accepted the rulers of Turfan and Kumul as Qing vassals. The Qing dynasty waged war against the Dzungars for decades until finally defeating them and then Qing Manchu Bannermen carried out the Zunghar genocide, nearly wiping them from existence and depopulating Dzungaria. The Qing then freed the Afaqi Khoja leader Burhan-ud-din and his brother Khoja Jihan from their imprisonment by the Dzungars, and appointed them to rule as Qing vassals over the Tarim Basin. The Khoja brothers decided to renege on this deal and declare themselves as independent leaders of the Tarim Basin. The Qing and the Turfan leader Emin Khoja crushed their revolt and China then took full control of both Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin by 1759.

Zunghar Genocide

The Dzungar (or Zunghar), Oirat Mongols who lived in an area that stretched from the west end of the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia (most of which is located in present-day Xinjiang), were the last nomadic empire to threaten China, which they did from the early 17th century through the middle of the 18th century.[39] After a series of inconclusive military conflicts that started in the 1680s, the Dzungars were subjugated by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in the late 1750s.

The Qing Empire, established by the Manchus in China, gained control over eastern Xinjiang as a result of a long struggle with the Dzungars that began in the seventeenth century. In 1755, the Qing Empire attacked Ghulja, and captured the Dzungar Khan. Over the next two years, the Manchus and Mongol armies of the Qing destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar Khanate, and attempted to divide the Xinjiang region into four sub-Khanates under four chiefs. Similarly, the Qing made members of a clan of Sufi shaykhs known as the Khojas, rulers in the western Tarim Basin, south of the Tianshan Mountains. In 1758–1759, however, rebellions against this arrangement broke out both north and south of the Tian Shan mountains.

After perpetrating wholesale massacres on the native Dzungar Oirat Mongol population in the Zunghar Genocide, in 1759, the Qing finally consolidated their authority by settling Chinese emigrants, together with a Manchu Qing garrison. The Qing put the whole region under the rule of a General of Ili (Chinese: 伊犁将军, Yili Jiangjün), headquartered at the fort of Huiyuan (the so-called "Manchu Kuldja", or Yili), 30 km west of Ghulja (Yining). The Qing dynasty Qianlong Emperor conquered the Jungharian (Dzungarian) plateau and the Tarim Basin, bringing the two separate regions, respectively north and south of the Tianshan mountains, under his rule as Xinjiang.[40] The south was inhabited by Turkic Muslims (Uyghurs) and the north by Junghar Mongols (Dzungars).[41] The Dzungars were also called "Eleuths" or "Kalmyks".

Clarke argued that the Qing campaign in 1757–58 "amounted to the complete destruction of not only the Zunghar state but of the Zunghars as a people."[42] After the Qianlong Emperor led Qing forces to victory over the Zunghar Oirat (Western) Mongols in 1755, he originally was going to split the Zunghar Empire into four tribes headed by four Khans, the Khoit tribe was to have the Zunghar leader Amursana as its Khan. Amursana rejected the Qing arrangement and rebelled since he wanted to be leader of a united Zunghar nation. Qianlong then issued his orders for the genocide and eradication of the entire Zunghar nation and name, Qing Manchu Bannermen and Khalkha (Eastern) Mongols enslaved Zunghar women and children while slaying the other Zunghars.[43]

The Qianlong Emperor issued direct orders for his commanders to "massacre" the Zunghars and "show no mercy", rewards were given to those who carried out the extermination and orders were given for young men to be slaughtered while women were taken as spoils. The Qing extirpated Zunghar identity from the remaining enslaved Zunghar women and children.[44] Orders were given to "completely exterminate" the Zunghar tribes, and this successful genocide by the Qing left Zungharia mostly unpopulated and vacant.[45] Qianlong ordered his men to- "Show no mercy at all to these rebels. Only the old and weak should be saved. Our previous campaigns were too lenient."[46] The Qianlong Emperor did not see any conflict between performing genocide on the Zunghars while upholding the peaceful principles of Confucianism, supporting his position by portraying the Zunghars as barbarian and subhuman. Qianlong proclaimed that "To sweep away barbarians is the way to bring stability to the interior.", that the Zunghars "turned their back on civilization.", and that "Heaven supported the emperor." in the destruction of the Zunghars.[47][48] According to the "Encyclopedia of genocide and crimes against humanity, Volume 3", per the United Nations Genocide Convention Article II, Qianlong's actions against the Zunghars constitute genocide, as he massacred the vast majority of the Zunghar population and enslaved or banished the remainder, and had "Zunghar culture" extirpated and destroyed.[49] Qianlong's campaign constituted the "eighteenth-century genocide par excellence."[50]

Qianlong emperor moved the remaining Zunghar people to China and ordered the generals to kill all the men in Barkol or Suzhou, and divided their wives and children to Qing soldiers.[51][52] In an account of the war, Qing scholar Wei Yuan, wrote that about 40% of the Zunghar households were killed by smallpox, 20% fled to Russia or the Kazakh Khanate, and 30% were killed by the army, leaving no yurts in an area of several thousands of li except those of the surrendered.[53][54][55][56][57] Clarke wrote 80%, or between 480,000 and 600,000 people, were killed between 1755 and 1758 in what "amounted to the complete destruction of not only the Zunghar state but of the Zunghars as a people."[53][58] 80% of the Zunghars died in the genocide.[59][60] The Zunghar genocide was completed by a combination of a smallpox epidemic and the direct slaughter of Zunghars by Qing forces made out of Manchu Bannermen and (Khalkha) Mongols.[61]

Anti-Zunghar Uyghur rebels from the Turfan and Hami oases had submitted to Qing rule as vassals and requested Qing help for overthrowing Zunghar rule. Uyghur leaders like Emin Khoja were granted titles within the Qing nobility, and these Uyghurs helped supply the Qing military forces during the anti-Zunghar campaign.[62][63][64] The Qing employed Khoja Emin in its campaign against the Zunghars and used him as an intermediary with Muslims from the Tarim Basin to inform them that the Qing were only aiming to kill Oirats (Zunghars) and that they would leave the Muslims alone, and also to convince them to kill the Oirats (Zunghars) themselves and side with the Qing since the Qing noted the Muslims' resentment of their former experience under Zunghar rule at the hands of Tsewang Araptan.[65]

It was not until generations later that Dzungaria rebounded from the destruction and near liquidation of the Zunghars after the mass slayings of nearly a million Zunghars.[66] Historian Peter Perdue has shown that the decimation of the Dzungars was the result of an explicit policy of extermination launched by Qianlong,[53] Perdue attributed the decimation of the Dzungars to a "deliberate use of massacre" and has described it as an "ethnic genocide".[67] Although this "deliberate use of massacre" has been largely ignored by modern scholars,[53] Dr. Mark Levene, a historian whose recent research interests focus on genocide,[68] has stated that the extermination of the Dzungars was "arguably the eighteenth century genocide par excellence."[69] The Dzungar (Zunghar) genocide has been compared to the Qing extermination of the Jinchuan Tibetan people in 1776.[70]

Demographic changes due to the genocide

The Qing "final solution" of genocide to solve the problem of the Zunghar Mongols, made the Qing sponsored settlement of millions of Han Chinese, Hui, Turkestani Oasis people (Uyghurs) and Manchu Bannermen in Dzungaria possible, since the land was now devoid of Zunghars.[53][71] The Dzungarian basin, which used to be inhabited by (Zunghar) Mongols, is currently inhabited by Kazakhs.[72] In northern Xinjiang, the Qing brought in Han, Hui, Uyghur, Xibe, and Kazakh colonists after they exterminated the Zunghar Oirat Mongols in the region, with one third of Xinjiang's total population consisting of Hui and Han in the northern are, while around two thirds were Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin.[73] In Dzungaria, the Qing established new cities like Urumqi and Yining.[74] The Qing were the ones who unified Xinjiang and changed its demographic situation.[75]

The depopulation of northern Xinjiang after the Buddhist Öölöd Mongols (Zunghars) were slaughtered, led to the Qing settling Manchu, Sibo (Xibe), Daurs, Solons, Han Chinese, Hui Muslims, and Turkic Muslim Taranchis in the north, with Han Chinese and Hui migrants making up the greatest number of settlers. Since it was the crushing of the Buddhist Öölöd (Dzungars) by the Qing which led to promotion of Islam and the empowerment of the Muslim Begs in southern Xinjiang, and migration of Muslim Taranchis to northern Xinjiang, it was proposed by Henry Schwarz that "the Qing victory was, in a certain sense, a victory for Islam".[76] Xinjiang as a unified, defined geographic identity was created and developed by the Qing. It was the Qing which led to Turkic Muslim power in the region increasing since the Mongol power was crushed by the Qing while Turkic Muslim culture and identity was tolerated or even promoted by the Qing.[77]

The Qing gave the name Xinjiang to Dzungaria after conquering it and wiping out the Dzungars, reshaping it from a steppe grassland into farmland cultivated by Han Chinese farmers, 1 million mu (17,000 acres) were turned from grassland to farmland from 1760-1820 by the new colonies.[78]

Qing rule

The Qing identified their state as "China" (Zhongguo), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in Manchu. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing state (including present day Manchuria, Dzungaria in Xinjiang, Mongolia, and other areas as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi ethnic state. The Qianlong Emperor explicitly commemorated the Qing conquest of the Zunghars as having added new territory in Xinjiang to "China", defining China as a multi ethnic state, rejecting the idea that China only meant Han areas in "China proper", meaning that according to the Qing, both Han and non-Han peoples were part of "China", which included Xinjiang which the Qing conquered from the Zunghars.[79] After the Qing were done conquering Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land which formerly belonged to the Zunghars, was now absorbed into "China" (Dulimbai Gurun) in a Manchu language memorial.[80][81][82] The Qing expounded on their ideology that they were bringing together the "outer" non-Han Chinese like the Inner Mongols, Eastern Mongols, Oirat Mongols, and Tibetans together with the "inner" Han Chinese, into "one family" united in the Qing state, showing that the diverse subjects of the Qing were all part of one family, the Qing used the phrase "Zhong Wai Yi Jia" 中外一家 or "Nei Wai Yi Jia" 內外一家 ("interior and exterior as one family"), to convey this idea of "unification" of the different peoples.[83] Xinjiang people were not allowed to be called foreigners (yi) under the Qing.[84]

The Qianlong Emperor rejected earlier ideas that only Han could be subjects of China and only Han land could be considered as part of China, instead he redefined China as multiethnic, saying in 1755 that "There exists a view of China (zhongxia), according to which non-Han people cannot become China's subjects and their land cannot be integrated into the territory of China. This does not represent our dynasty's understanding of China, but is instead that of the earlier Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties."[85] The Manchu Qianlong Emperor rejected the views of Han officials who said Xinjiang was not part of China and that he should not conquer it, putting forth the view that China was multiethnic and did not just refer to Han.[86] Han migration to Xinjiang was permitted by the Manchu Qianlong Emperor, who also gave Chinese names to cities to replace their Mongol names, instituting civil service exams in the area, and implementing the county and prefecture Chinese style administrative system, and promoting Han migration to Xinjiang to solidify Qing control was supported by numerous Manchu officials under Qianlong.[87] A proposal was written in The Imperial Gazetteer of the Western Regions (Xiyu tuzhi) to use state-funded schools to promote Confucianism among Muslims in Xinjiang by Fuheng and his team of Manchu officials and the Qianlong Emperor.[88] Confucian names were given to towns and cities in Xinjiang by the Qianlong Emperor, like "Dihua" for Urumqi in 1760 and Changji, Fengqing, Fukang, Huifu, and Suilai for other cities in Xinjiang, Qianlong also implemented Chinese style prefectures, departments, and counties in a portion of the region.[89]

The Qing Qianlong Emperor compared his achievements with that of the Han and Tang ventures into Central Asia.[90] Qianlong's conquest of Xinjiang was driven by his mindfulness of the examples set by the Han and Tang[91] Qing scholars who wrote the official Imperial Qing gazetteer for Xinjiang made frequent references to the Han and Tang era names of the region.[92] The Qing conqueror of Xinjiang, Zhao Hui, is ranked for his achievements with the Tang dynasty General Gao Xianzhi and the Han dynasty Generals Ban Chao and Li Guangli.[93] Both aspects pf the Han and Tang models for ruling Xinjiang were adopted by the Qing and the Qing system also superficially resembled that of nomadic powers like the Qara Khitay, but in reality the Qing system was different from that of the nomads, both in terms of territory conquered geographically and their centralized administrative system, resembling a western stye (European and Russian) system of rule.[94] The Qing portrayed their conquest of Xinjiang in officials works as a continuation and restoration of the Han and Tang accomplishments in the region, mentioning the previous achievements of those dynasties.[95] The Qing justified their conquest by claiming that the Han and Tang era borders were being restored,[96] and identifying the Han and Tang's grandeur and authority with the Qing.[97] Many Manchu and Mongol Qing writers who wrote about Xinjiang did so in the Chinese language, from a culturally Chinese point of view.[98] Han and Tang era stories about Xinjiang were recounted and ancient Chinese places names were reused and circulated.[99] Han and Tang era records and accounts of Xinjiang were the only writings on the region available to Qing era Chinese in the 18th century and needed to be replaced with updated accounts by the literati.[100][101]

Xinjiang at this time did not exist as one unit. It consisted of the two separate political entities of Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin (Eastern Turkestan).[102][103][104][105] There was the Zhunbu (Dzungar region) and Huibu (Muslim region).[106] Dzungaria or Ili was called Zhunbu 準部 (Dzungar region) Tianshan Beilu 天山北路 (Northern March), "Xinjiang" 新疆 (New Frontier),[107] Dzongarie, Djoongaria,[108] Soungaria,[109][110] or "Kalmykia" (La Kalmouquie in French).[111][112] It was formerly the area of the Zunghar Khanate 準噶爾汗國, the land of the Dzungar Oirat Mongols. The Tarim Basin was known as "Tianshan Nanlu 天山南路 (southern March), Huibu 回部 (Muslim region), Huijiang 回疆 (Muslim frontier), Chinese Turkestan, Kashgaria, Little Bukharia, East Turkestan", and the traditional Uyghur name for it was Altishahr (Uyghur: التى شهر, ULY: Altä-shähär).[113] It was formerly the area of the Eastern Chagatai Khanate 東察合台汗國, land of the Uyghur people before being conquered by the Dzungars. The Chinese Repository said that "Neither the natives nor the Chinese appear to have any general name to designate the Mohammedan colonies. They are called Kashgar, Bokhára, Chinese Turkestan, &c., by foreigners, none of which seem to be very appropriate. They have also been called Jagatai, after a son of Genghis khan, to whom this country fell as his portion after his father’s death, and be included all the eight Mohammedan cities, with some of the surrounding countries, in one kingdom. It is said to have remained in this family, with some interruptions, until conquered by the Eleuths of Soungaria in 1683."[109][110]

Between Jiayu Guan's west and Urumchi's East, an area of Xiniiang was also disginated as Tianshan Donglu 天山東路 (Eastern March).[114][115] The three routes that made up Xinjiang were - Tarim Basin (southern route), Dzungaria (northern route), and the Turfan Basin (eastern route with Turfan, Hami, and Urumqi).[116]

After Qing dynasty defeated the Dzungar Oirat Mongols and exterminated them from their native land of Dzungaria in the genocide, the Qing settled Han, Hui, Manchus, Xibe, and Taranchis (Uyghurs) from the Tarim Basin, into Dzungaria. Han Chinese criminals and political exiles were exiled to Dzhungaria, such as Lin Zexu. Chinese Hui Muslims and Salar Muslims belonging to banned Sufi orders like the Jahriyya were also exiled to Dzhungaria as well. In the aftermath of the crushing of the 1781 Jahriyya rebellion, Jahriyya adherents were exiled.

The Qing enacted different policies for different areas of Xinjiang. Han and Hui migrants were urged by the Qing government to settled in Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang, while they were not allowed in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin oases with the exception of Han and Hui merchants.[117] In areas where more Han Chinese settled like in Dzungaria, the Qing used a Chinese style administrative system.[118]

The Manchu Qing ordered the settlement of thousands of Han Chinese peasants in Xinijiang after 1760, the peasants originally came from Gansu and were given animals, seeds, and tools as they were being settled in the area, for the purpose of making China's rule in the region permanent and a fait accompli.[119]

Taranchi was the name for Turki (Uyghur) agriculturalists who were resettled in Dzhungaria from the Tarim Basin oases ("East Turkestani cities") by the Qing dynasty, along with Manchus, Xibo (Xibe), Solons, Han and other ethnic groups in the aftermath of the destruction of the Dzhunghars.[120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127][128][129][130][131][132] Kulja (Ghulja) was a key area subjected to the Qing settlement of these different ethnic groups into military colonies.[133] The Manchu garrisons were supplied and supported with grain cultivated by the Han soldiers and East Turkestani (Uyghurs) who were resettled in agricultural colonies in Zungharia.[113] The Manchu Qing policy of settling Chinese colonists and Taranchis from the Tarim Basin on the former Kalmucks (Dzungar) land was described as having the land "swarmed" with the settlers.[134][135] The amount of Uyghurs moved by the Qing from Altä-shähär (Tarim Basin) to depopulated Zunghar land in Ili numbered around 10,000 families.[136][137][138] The amount of Uyghurs moved by the Qing into Jungharia (Dzungaria) at this time has been described as "large".[139] The Qing settled in Dzungaria even more Turki-Taranchi (Uyghurs) numbering around 12,000 families originating from Kashgar in the aftermath of the Jahangir Khoja invasion in the 1820s.[140] Standard Uyghur is based on the Taranchi dialect, which was chosen by the Chinese government for this role.[141] Salar migrants from Amdo (Qinghai) came to settle the region as religious exiles, migrants, and as soldiers enlisted in the Chinese army to fight in Ili, often following the Hui.[142]

After a revolt by the Xibe in Qiqihar in 1764, the Qianlong Emperor ordered an 800-man military escort to transfer 18,000 Xibe to the Ili valley of Dzungaria in Xinjiang.[143][144] In Ili, the Xinjiang Xibe built Buddhist monasteries and cultivated vegetables, tobacco, and poppies.[145] One punishment for Bannermen for their misdeeds involved them being exiled to Xinjiang.[146]

In 1765, 300,000 ch'ing of land in Xinjiang were turned into military colonies, as Chinese settlement expanded to keep up with China's population growth.[147]

The Qing resorted to incentives like issuing a subsidy which was paid to Han who were willing to migrate to northwest to Xinjiang, in a 1776 edict.[148][149] There were very little Uyghurs in Urumqi during the Qing dynasty, Urumqi was mostly Han and Hui, and Han and Hui settlers were concentrated in Northern Xinjiang (Beilu aka Dzungaria). Around 155,000 Han and Hui lived in Xinjiang, mostly in Dzungaria around 1803, and around 320,000 Uyghurs, living mostly in Southern Xinjiang (the Tarim Basin), as Han and Hui were allowed to settle in Dzungaria but forbidden to settle in the Tarim, while the small amount of Uyghurs living in Dzungaria and Urumqi was insignificant.[150][151][152] Hans were around one third of Xinjiang's population at 1800, during the time of the Qing Dynasty.[153] Spirits (alcohol) were introduced during the settlement of northern Xinjiang by Han Chinese flooding into the area.[154] The Qing made a special case in allowing northern Xinjiang to be settled by Han, since they usually did not allow frontier regions to be settled by Han migrants. This policy led to 200,000 Han and Hui settlers in northern Xinjiang when the 18th century came to a close, in addition to military colonies settled by Han called Bingtun.[155]

Professor of Chinese and Central Asian History at Georgetown University, James A. Millward wrote that foreigners often mistakenly think that Urumqi was originally a Uyghur city and that the Chinese destroyed its Uyghur character and culture, however, Urumqi was founded as a Chinese city by Han and Hui (Tungans), and it is the Uyghurs who are new to the city.[156][157]

While a few people try to give a misportrayal of the historical Qing situation in light of the contemporary situation in Xinjiang with Han migration, and claim that the Qing settlements and state farms were an anti-Uyghur plot to replace them in their land, Professor James A. Millward pointed out that the Qing agricultural colonies in reality had nothing to do with Uyghur and their land, since the Qing banned settlement of Han in the Uyghur Tarim Basin and in fact directed the Han settlers instead to settle in the non-Uyghur Dzungaria and the new city of Urumqi, so that the state farms which were settled with 155,000 Han Chinese from 1760-1830 were all in Dzungaria and Urumqi, where there was only an insignificant amount of Uyghurs, instead of the Tarim Basin oases. [158]

Han and Hui merchants were initially only allowed to trade in the Tarim Basin, while Han and Hui settlement in the Tarim Basin was banned, until the Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion, in 1830 when the Qing rewarded the merchants for fighting off Khoja by allowing them to settle down.[159] Robert Michell noted that as of 1870, there were many Chinese of all occupations living in Dzungaria and they were well settled in the area, while in Turkestan (Tarim Basin) there were only a few Chinese merchants and soldiers in several garrisons among the Muslim population.[102][103]

At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang.[160] A census of Xinjiang under Qing rule in the early 19th century tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 30% Han and 60% Turkic, while it dramatically shifted to 6% Han and 75% Uyghur in the 1953 census, however a situation similar to the Qing era-demographics with a large number of Han has been restored as of 2000 with 40.57% Han and 45.21% Uyghur.[161] Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's demographic situation is similar to that of the early Qing period in Xinjiang.[73] Before 1831, only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in southern Xinjiang oases (Tarim Basin) and only a few Uyghurs lived in northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria).[162]

Kalmyk Oirats return

The Oirat Mongol Kalmyk Khanate was founded in the 17th century with Tibetan Buddhism as its main religion, following the earlier migration of the Oirats from Zungharia through Central Asia to the steppe around the mouth of the Volga River. During the course of the 18th century, they were absorbed by the Russian Empire, which was then expanding to the south and east. The Russian Orthodox church pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. In the winter of 1770–1771, about 300,000 Kalmyks set out to return to China. Their goal was to retake control of Zungharia from the Qing dynasty of China.[163] Along the way many were attacked and killed by Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, their historical enemies based on inter-tribal competition for land, and many more died of starvation and disease. After several grueling months of travel, only one-third of the original group reached Zungharia and had no choice but to surrender to the Qing upon arrival.[164] These Kalmyks became known as Oirat Torghut Mongols. After being settled in Qing territory, the Torghuts were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them. They proved to be incompetent farmers and they became destitute, selling their children into slavery, engaging in prostitution, and stealing, according to the Manchu Qi-yi-shi.[165][166] Child slaves were in demand on the Central Asian slave market, and Torghut children were sold into this slave trade.[167]

Kokandi attacks

In 1827, southern part of Xinjiang was retaken by former ruler's descendant Jihangir Khojah; Chang-lung, the Chinese general of Hi, recovered possession of Kashgar and the other revolted cities in 1828.[168] A revolt in 1829 under Mohammed AH Khan and Yusuf, brother of Jihangir Khojah, was more successful, and resulted in the concession of several important trade privileges to the of the district of Alty Shahr (the "six cities"). Until 1846 the country enjoyed peace under the just and liberal rule of Zahir-ud-din, the Uyghur governor, but in that year a fresh Khojah revolt under Kath Tora led to his making himself master of the city, with circumstances of unbridled license and oppression. His reign was, however, brief, for at the end of seventy-five days, on the approach of the Chinese, he fled back to Khokand amid the jeers of the inhabitants. The last of the Khojah revolts (1857) was of about equal duration with the previous one, and took place under Wali-Khan. The great Tungani revolt, or insurrection of the Chinese Muslims, which broke out in 1862 in Gansu, spread rapidly to Zungaria and through the line of towns in the Tarim basin. The Tungani troops in Yarkand rose, and (10 August 1863) massacred some seven thousand Chinese, while the inhabitants of Kashgar, rising in their turn against their masters, invoked the aid of Sadik Beg, a Kyrgyz chief, who was reinforced by Buzurg Khan, the heir of Jahanghir, and Yakub Beg, his general, these being despatched at Sadik's request by the ruler of Khokand to raise what troops they could to aid Muslims in Kashgar. Sadik Beg soon repented of having asked for a Khojah, and eventually marched against Kashgar, which by this time had succumbed to Buzurg Khan and Yakub Beg, but was defeated and driven back to Khokand. Buzurg Khan delivered himself up to indolence and debauchery, but Yakub Beg, with singular energy and perseverance, made himself master of Yangi Shahr, Yangi-Hissar, Yarkand, and other towns, and eventually declared himself the Amir of Kashgaria.[169]

Yakub Beg ruled at the height of The Great Game era when the British, Russian, and Manchu Qing empires were all vying for Central Asia. Kashgaria extended from the capital Kashgar in south-western Xinjiang to Ürümqi, Turfan, and Hami in central and eastern Xinjiang more than a thousand kilometers to the north-east, including a majority of what was known at the time as East Turkestan.[170]

Kashgar and the other cities of the Tarim basin remained under Yakub Beg's rule until December 1877. Yakub Beg's rule lasted until General Zuo Zongtang (also known as General Tso) reconquered the region in 1877 for Qing China. In 1881, Qing China recovered the Gulja region through diplomatic negotiations (Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881)).

Yaqub Beg and his Turkic Uyghur Muslims also declared a Jihad against Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang. Yaqub went as far as to enlist Han Chinese to help fight against Chinese Muslim forces.[171] Turkic Muslims also massacred Chinese Muslims in Ili.[172]

Conversion of Xinjiang into a province

In 1884, Qing China renamed the conquered region, established Xinjiang ("new frontier") as a province, formally applying onto it the political system of China proper. For the 1st time the name "Xinjiang" replaced old historical names such as "Western Regions", "Chinese Turkestan", "Eastern Turkestan", "Uyghuristan", "Kashgaria", "Uyghuria", "Alter Sheher" and "Yetti Sheher".

The two separate regions, Dzungaria, known as Zhunbu 準部 (Dzungar region) or Tianshan Beilu 天山北路 (Northern March),[107][173][174] and the Tarim Basin, which had been known as Altishahr, Huibu (Muslim region), Huijiang (Muslim-land) or "Tianshan Nanlu 天山南路 (southern March),[113][175] were combined into a single province called Xinjiang by in 1884.[176] Before this, there was never one administrative unit in which North Xinjiang (Zhunbu) and Southern Xinjiang (Huibu) were integrated together.[177]

A lot of the Han Chinese and Chinese Hui Muslim population who had previously settled northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria) after the Qing genocide of the Dzungars, had died in the Dungan revolt (1862–77). As a result, new Uyghur colonists from Southern Xinjiang (the Tarim Basin) proceeded to settle in the newly empty lands and spread across all of Xinjiang.

After Xinjiang was converted into a province by the Qing, the provincialisation and reconstruction programs initiated by the Qing resulted in the Chinese government helping Uyghurs migrate from southern Xinjiang to other areas of the province, like the area between Qitai and the capital, which was formerly nearly completely inhabited by Han Chinese, and other areas like Urumqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor, and the Tarim River's lower reaches.[178] It was during Qing times that Uyghurs were settled throughout all of Xinjiang, from their original home cities in the western Tarim Basin. The Qing policies after they created Xinjiang by uniting Zungharia and Altishahr (Tarim Basin) led Uyghurs to believe that the all of Xinjiang province was their homeland, since the annihilation of the Zunghars (Dzungars) by the Qing, populating the Ili valley with Uyghurs from the Tarim Basin, creating one political unit with a single name (Xinjiang) out of the previously separate Zungharia and the Tarim Basin, the war from 1864-1878 which led to the killing of much of the original Han Chinese and Chinese Hui Muslims in Xinjiang, led to areas in Xinjiang with previously had insignificant amounts of Uyghurs, like the southeast, east, and north, to then become settled by Uyghurs who spread through all of Xinjiang from their original home in the southwest area. There was a major and fast growth of the Uyghur population, while the original population of Han Chinese and Hui Muslims from before the war of 155,000 dropped, to the much lower population of 33,114 Tungans (Hui) and 66,000 Han.[179]

A regionalist style nationalism was fostered by the Han Chinese officials who came to rule Xinjiang after its conversion into a province by the Qing, it was from this ideology that the later East Turkestani nationalists appropriated their sense of nationalism centered around Xinjiang as a clearly defined geographic territory.[75]

20th Century and after the Qing Dynasty

In 1912 the Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. Yuan Dahua, the last Qing governor of Xinjiang, fled. One of his subordinates Yang Zengxin, acceded to the Republic of China in March of the same year, and maintained control of Xinjiang until his death in 1928.

Mongols have at times advocated for the historical Oirat Dzungar Mongol area of Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang, to be annexed to the Mongolian state in the name of Pan-Mongolism.

Legends grew among the remaining Oirats that Amursana had not died after he fled to Russia, but was alive and would return to his people to liberate them from Manchu Qing rule and restore the Oirat nation. Prophecies had been circulating about the return of Amursana and the revival of the Oirats in the Altai region.[180][181] The Oirat Kalmyk Ja Lama claimed to be a grandson of Amursana and then claimed to be a reincarnation of Amursana himself, preaching anti-Manchu propaganda in western Mongolia in the 1890s and calling for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.[182] Ja Lama was arrested and deported several times. However, he returned to the Oirat Torghuts in Altay (in Dzungaria) in 1910 and in 1912 he helped the Outer Mongolians mount an attack on the last Qing garrison at Kovd, where the Manchu Amban was refusing to leave and fighting the newly declared independent Mongolian state.[183][184][185][186][187][188] The Manchu Qing force was defeated and slaughtered by the Mongols after Khovd fell.[189][190]

Ja Lama told the Oirat remnants in Xinjiang: "I am a mendicant monk from the Russian Tsar's kingdom, but I am born of the great Mongols. My herds are on the Volga river, my water source is the Irtysh. There are many hero warriors with me. I have many riches. Now I have come to meet with you beggars, you remnants of the Oirats, in the time when the war for power begins. Will you support the enemy? My homeland is Altai, Irtysh, Khobuk-sari, Emil, Bortala, Ili, and Alatai. This is the Oirat mother country. By descent, I am the great-grandson of Amursana, the reincarnation of Mahakala, owning the horse Maralbashi. I am he whom they call the hero Dambijantsan. I came to move my pastures back to my own land, to collect my subject households and bondservants, to give favour, and to move freely."[191][192]

Ja Lama built an Oirat fiefdom centered around Kovd,[193] he and fellow Oirats from Altai wanted to emulate the original Oirat empire and build another grand united Oirat nation from the nomads of western China and Mongolia,[194] but was arrested by Russian Cossacks and deported in 1914 on the request of the Monglian government after the local Mongols complained of his excesses, and out of fear that he would create an Oirat separatist state and divide them from the Khalkha Mongols.[195] Ja Lama returned in 1918 to Mongolia and resumed his activities and supported himself by extorting passing caravans,[196][197][198] but was assassinated in 1922 on the orders of the new Communist Mongolian authorities under Damdin Sükhbaatar.[199][200][201]

The part Buryat Momgol Transbaikalian Cossack Ataman Grigory Semyonov declared a "Great Mongol State" in 1918 and had designs to unify the Oirat Mongol lands, portions of Xinjiang, Transbaikal, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Tannu Uriankhai, Khovd, Hu-lun-pei-erh and Tibet into one Mongolian state.[202]

The Buryat Mongol Agvan Dorzhiev tried advocating for Oirat Mongol areas like Tarbagatai, Ili, and Altai to get added to the Outer Mongolian state.[203] Out of concern that China would be provoked, this proposed addition of the Oirat Dzungaria to the new Outer Mongolian state was rejected by the Soviets.[204]

Following insurgencies against Governor Jin Shuren in the early 1930s, a rebellion in Kashgar led to the establishment of the short-lived First East Turkistan Republic (First ETR) in 1933. The ETR claimed authority around the Tarim Basin from Aksu in the north to Khotan in the south, and was suppressed by the armies of the Chinese Muslim warlord Ma Zhongying in 1934.

In 1933, Sheng Shicai, a Chinese warlord, seized control of Xinjiang with support from the Soviet Union, which helped him defeat Ma Zhongying. Sheng ruled the region for a decade during which he permitted greater Soviet influence on Xinjiang's ethnic, economic and security policies. Sheng invited a group of Chinese Communists to Xinjiang including Mao Zedong's brother Mao Zemin, but in 1943, fearing a conspiracy against him, Sheng killed all Chinese Communists, including Mao Zemin. In the summer of 1944, during the Ili Rebellion, a Second East Turkistan Republic (Second ETR) was established, this time, with Soviet support, in what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in northern Xinjiang. The Three Districts Revolution, as it is known in China, threatened the Nationalist provincial government in Ürümqi. Sheng Shicai fell from power and Zhang Zhizhong was sent from Nanjing to negotiate a truce with the Second ETR and the USSR. An uneasy coalition provincial government was formed and brought nominal unity to Xinjiang with separate administrations.

The coalition government came to an end at the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War when the victorious Chinese Communists entered Xinjiang in 1949. The leadership of the Second ETR was persuaded by the Soviet Union to negotiate with the Chinese Communists. Most were killed in an airplane crash en route to a peace conference in Beijing in late August. The remaining leadership under Saifuddin Azizi agreed to join the newly founded People's Republic of China. The Nationalist military commanders in Xinjiang, Tao Zhiyue and provincial governor Burhan Shahidis surrendered to the People's Liberation Army (PLA) in September. Kazak militias under Osman Batur resisted the PLA into the early 1950s. The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the PRC was established on October 1, 1955, replacing Xinjiang Province.

PRC rule

Uyghur nationalists often incorrectly claim that 5% of Xinjiang's population in 1949 was Han, and that the other 95% was Uyghur, erasing the presence of Kazakhs, Xibes, and others, and ignoring the fact that Hans were around one third of Xinjiang's population at 1800, during the time of the Qing Dynasty.[153]

In 1955 (the first modern census in China was taken in 1953), Uyghurs were counted as 73% of Xinjiang's total population of 5.11 million.[205] Although Xinjiang as a whole is designated as a "Uyghur Autonomous Region", since 1954 more than 50% of Xinjiang's land area are designated autonomous areas for 13 native non-Uyghur groups.[206] The modern Uyghur people experienced ethnogenesis especially from 1955, when the PRC officially recognized that ethnic category - in opposition to the Han - of formerly separately self-identified oasis peoples.[207]

The People's Republic of China has directed the majority of Han migrants towards the sparsely populated Dzungaria (Junggar Basin), before 1953 most of Xinjiang's population (75%) lived in the Tarim Basin, so the new Han migrants resulted in the distribution of population between Dzungaria and the Tarim being changed.[208][209][210] Most new Chinese migrants ended up in the northern region, in Dzungaria.[211] Han and Hui made up the majority of the population in Dzungaria's cities while Uighurs made up most of the population in Kashgaria's cities.[212] Eastern and Central Dzungaria are the specific areas where these Han and Hui are concentrated.[213] China made sure that new Han migrants were settled in entirely new areas uninhabited by Uyghurs so as to not disturb the already existing Uyghur communities.[214] Lars-Erik Nyman noted that Kashgaria was the native land of the Uighurs, "but a migration has been in progress to Dzungaria since the 18th century".[215]

Both Han economic migrants from other parts of China and Uyghur economic migrants from southern Xinjiang have been flooding into northern Xinjiang since the 1980s.[216]

Southern Xinjiang is where the majority of the Uyghur population resides, while it is in Northern Xinjiang cities where the majority of the Han (90%) population of Xinjiang reside.[217] Southern Xinjiang is dominated by its nine million Uighur majority population, while northern Xinjiang is where the mostly urban Han population holds sway.[218] This situation has been followed by an imbalance in the economic situation between the two ethnic groups, since the Northern Junghar Basin (Dzungaria) has been more developed than the Uighur south.[219]

From the 1950s to 1970s, 92% of migrants to Xinjiang were Han and 8% were Hui. Most of these migrants were unorganized settlers - "as [they are still] now", coming from neighboring Gansu province to seek trading opportunities.[220]

The Soviet Union incited separatist activities in Xinjiang through propaganda, encouraging Kazakhs to flee to the Soviet Union and attacking China. China responded by reinforcing the Xinjiang-Soviet border area specifically with Han Bingtuan militia and farmers.[221] The Soviets massively intensified their broadcasts inciting Uyghurs to revolt against the Chinese via Radio Tashkent since 1967 and directly harbored and supported separatist guerilla fighters to attack the Chinese border, in 1966 the amount of Soviet sponsored separatist attacks on China numbered 5,000.[222] The Soviets transmitted a radio broadcast from Radio Tashkent into Xinjiang on 14 May 1967, boasting of the fact that the Soviets had supported the Second East Turkestan Republic against China.[223] In addition to Radio Tashkent, other Soviet media outlets aimed at disseminating propaganda towards Uyghurs urging that they proclaim independence and revolt against China included Radio Alma-Ata and the Alma-Ata published Sherki Türkistan Evazi ("The Voice of Eastern Turkestan") newspaper.[224] After the Sino-Soviet split in 1962, over 60,000 Uyghurs and Kazakhs defected from Xinjiang to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, in response to Soviet propaganda which promised Xinjiang independence. Uyghur exiles later threatened China with rumors of a Uyghur "liberation army" in the thousands that were supposedly recruited from Sovietized emigres.[225]

The Soviet Union was involved in funding and support to the East Turkestan People's Revolutionary Party (ETPRP), the largest militant Uyghur separatist organization in its time, to start a violent uprising against China in 1968.[226][227][228][229][230] In the 1970s, the Soviets also supported the United Revolutionary Front of East Turkestan (URFET) to fight against the Chinese.[231]

"Bloody incidents" in 1966-67 flared up as Chinese and Soviet forces clashed along the border as the Soviets trained anti-Chinese guerillas and urged Uyghurs to revolt against China, hailing their "national liberation struggle".[232] In 1969, Chinese and Soviet forces directly fought each other along the Xinjiang-Soviet border.[233][234][235][236]

The Soviet Union supported Uyghur nationalist propaganda and Uyghur separatist movements against China. The Soviet historians claimed that the Uyghur native land was Xinjiang and Uyghur nationalism was promoted by Soviet versions of history on turcology.[237] Soviet turcologists like D.I. Tikhonov wrote pro-independence works on Uyghur history and the Soviet supported Uyghur historian Tursun Rakhimov wrote more historical works supporting Uyghur independence and attacking the Chinese government, claiming that Xinjiang was an entity created by China made out of the different parts of East Turkestan and Zungharia.[238] These Soviet Uyghur historians were waging an "ideological war" against China, emphasizing the "national liberation movement" of Uyghurs throughout history.[239] The Soviet Communist Party supported the publication of works which glorified the Second East Turkestan Republic and the Ili Rebellion against China in its anti-China propaganda war.[240] Soviet propaganda writers wrote works claiming that Uyghurs lived better lives and were able to practice their culture only in Soviet Central Asia and not in Xinjiang.[241] In 1979 Soviet KGB agent Victor Louis wrote a thesis claiming that the Soviets should support a "war of liberation" against the "imperial" China to support Uighur, Tibetan, Mongol, and Manchu independence.[242][243] The Soviet KGB itself supported Uyghur separatists against China.[244]

Uyghur nationalist historian Turghun Almas and his book Uyghurlar (The Uyghurs) and Uyghur nationalist accounts of history were galvanized by Soviet stances on history, "firmly grounded" in Soviet Turcological works, and both heavily influenced and partially created by Soviet historians and Soviet works on Turkic peoples.[245] Soviet historiography spawned the rendering of Uyghur history found in Uyghurlar.[246] Almas claimed that Central Asia was "the motherland of the Uyghurs" and also the "ancient golden cradle of world culture".[247]

Xinjiang's importance to China increased after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, leading to China's perception of being encircled by the Soviets.[248] The China supported the Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet invasion, and broadcast reports of Soviet atrocities on Afghan Muslims to Uyghurs in order to counter Soviet propaganda broadcasts into Xinjiang, which boasted that Soviet minorities lived better and incited Muslims to revolt.[249] Chinese radio beamed anti-Soviet broadcasts to Central Asian ethnic minorities like the Kazakhs.[233] The Soviets feared disloyalty among the non-Russian Kazakh, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz in the event of Chinese troops attacking the Soviet Union and entering Central Asia. Russians were goaded with the taunt "Just wait till the Chinese get here, they'll show you what's what!" by Central Asians when they had altercations.[250] The Chinese authorities viewed the Han migrants in Xinjiang as vital to defending the area against the Soviet Union.[251] China opened up camps to train the Afghan Mujahideen near Kashgar and Khotan and supplied them with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of small arms, rockets, mines, and anti-tank weapons.[252][253]

Since the Chinese economic reform from the late 1970s has exacerbated uneven regional development, more Uyghurs have migrated to Xinjiang cities and some Hans have also migrated to Xinjiang for independent economic advancement. Increased ethnic contact and labor competition coincided with Uyghur separatist terrorism from the 1990s, such as the 1997 Ürümqi bus bombings.[254]

In the 1980s, 90% of Xinjiang Han lived in north Xinjiang (Jiangbei, historical Dzungaria). In the mid-1990s, Uyghurs consisted of 90% of south Xinjiang (Nanjiang, historical Tarim)'s population.[220] In 1980, the liberal reformist Hu Yaobang announced the expulsion of ethnic Han cadres in Xinjiang to eastern China. Hu was purged in 1987 for a series of demonstrations that he is said to have provoked in other areas of China. The prominent Xinjiang and national official Wang Zhen criticized Hu for destroying Xinjiang Han cadres' "sense of security", and for exacerbating ethnic tensions.[255]

In the 1990s, there was a net inflow of Han people to Xinjiang, many of whom were previously prevented from moving because of the declining number of social services tied to hukou (residency permits).[256] As of 1996, 13.6% of Xinjiang's population was employed by the publicly traded Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Bingtuan) corporation. 90% of the Bingtuan's activities relate to agriculture, and 88% of Bingtuan employees are Han, although the percentage of Hans with ties to the Bingtuan has decreased.[257] Han emigration from Xinjiang has also resulted in an increase of minority-identified agricultural workers as a total percentage of Xinjiang's farmers, from 69.4% in 1982 to 76.7% in 1990.[258] During the 1990s, about 1.2 million temporary migrants entered Xinjiang every year to stay for the cotton picking season.[259] Many Uyghur trading communities exist outside of Xinjiang; the largest in Beijing is one village of a few thousand.[259]

A chain of aggressive and belligerent press releases in the 1990s making false claims about violent insurrections in Xinjiang, and exaggerating both the number of Chinese migrants and the total number of Uyghurs in Xinjiang were made by the former Soviet supported URFET leader Yusupbek Mukhlisi.[260][261]

In 2000, Uyghurs "comprised 45 per cent of Xinjiang's population, but only 12.8 per cent of Urumqi's population." Despite having 9% of Xinjiang's population, Urumqi accounts for 25% of the region's GDP, and many rural Uyghurs have been migrating to that city to seek work in the dominant light, heavy, and petrochemical industries.[262] Hans in Xinjiang are demographically older, better-educated, and work in higher-paying professions than their Uyghur cohabitants. Hans are more likely to cite business reasons for moving to Urumqi, while some Uyghurs also cite trouble with the law back home and family reasons for their moving to Urumqi.[263] Hans and Uyghurs are equally represented in Urumqi's floating population that works mostly in commerce. Self-segregation within the city is widespread, in terms of residential concentration, employment relationships, and a social norm of endogamy.[264] As of 2010, Uyghurs constitute a majority in the Tarim Basin, and a mere plurality in Xinjiang as a whole.[265]

Han and Hui mostly live in northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria), and are separated from areas of historical Uyghur dominance south of the Tian Shan mountains (southwestern Xinjiang), where Uyghurs account for about 90% of the population.[266]

Continued tensions

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch speculate that Uyghur resentment towards alleged repression of Uyghur culture may explain some of the ethnic riots that have occurred in Xinjiang during the PRC period.

Conversely, Han Chinese are treated as second class citizens by PRC policies, in which many of the ethnic autonomy policies are discriminatory against them (see autonomous entities of China) and previous Chinese dynasties owned Xinjiang before the Uyghur Empire. Independence advocates view Chinese rule in Xinjiang, and policies like the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps as Chinese imperialism.

In the 1980s there was a scattering of student demonstrations and riots against police action that took on an ethnic aspect; and the Baren Township riot in April, 1990, an abortive uprising, resulted in more than 50 deaths.

A police round-up and execution of 30 suspected separatists[267] during Ramadan resulted in large demonstrations in February 1997 which were characterised as riots in the Chinese state media,[268] which western have described as peaceful.[269] These demonstrations culminated in the Gulja Incident on 5 February, where a PLA crackdown on the demonstrations led to at least 9 deaths and perhaps more than 100.[267] The Ürümqi bus bombs of February 25, 1997, killed 9 and injured 68. The situation in Xinjiang was relatively quiet from the late nineties through mid-2006, though inter-ethnic tensions no doubt remained.[270]

Recent incidents include the 2007 Xinjiang raid,[271] a thwarted 2008 suicide bombing attempt on a China Southern Airlines flight,[272] and the 2008 Xinjiang attack which resulted in the deaths of sixteen police officers four days before the Beijing Olympics.[273][274] Further incidents include the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, the September 2009 Xinjiang unrest, and the 2010 Aksu bombing that led to the trials of 376 people.[275] The 2011 Hotan attack in July led to the deaths of 18 civilians. Although all of the attackers were Uyghur,[276] both Han and Uyghur people were victims.[277]

See also

- Indo-Aryan migration hypothesis

- Turkic migration

Notes

This article incorporates text from Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China, by Robert Samuel Maclay, a publication from 1861 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China, by Robert Samuel Maclay, a publication from 1861 now in the public domain in the United States.