History of Tuva

Tuva is named after the Turkic Tuvan (Tuva) people, also known as Tuba, Toba, Tubalars, Old Turkic Tabgach, Ch. Tuoba (拓拔). The other appellation of the Tuvan people is Uriankhai, extensively used during the Russian colonization period and in the first Russian scientific reports on the Zungaria populations. A main source with a rough outline of the Tuvan people remains the work of L.P. Potapov (1969).[1] In the recent past, Tuvan territory has been of roughly the same geographical area.

Early history

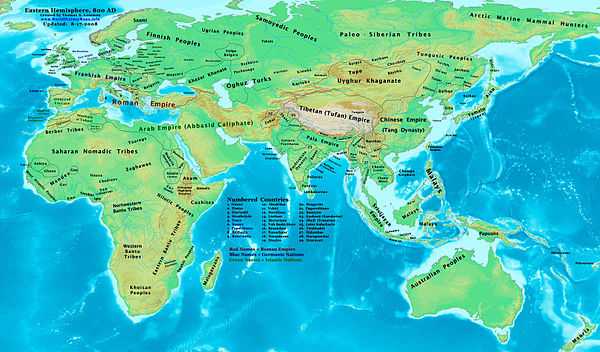

The history of Tannu Uriankhai prior to the mid-18th century is poorly understood. There are few written sources; moreover, these sources often do not distinguish between the Tannu Uriankhai, the Altai Uriankhai, or the Altainor Uriankhai. In general, the land has played only a passive role in the history of Inner Asia, passed from one conqueror to another more as a legacy than as a conquest. It was dominated by a series of Turkic khanates of northern Mongolia—Turks, Uighurs, and Kirghiz—although it appears that the real Turkicisation of the region began with the flight of Turkic tribes into this area after the rise of Genghis Khan in the 13th century.

Probably the most spectacular Scythian finds known to archaeologists have been discovered in northern Tuva near Arzhaan. Dating from the 7th and 6th centuries BC they are also among the earliest known, as well as the easternmost. Following restoration in St Petersburg, the sumptuous gold treasure hoard is now on display in the new National Museum in Kyzyl.

The Xiongnu (BC 209-93 AD) ruled over the area of Tuva prior to 200 AD. The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses and proposals by scholars including Mongolic and Turkic. At this time a people known to the Chinese as Dingling inhabited the region. The Chinese recorded the existence of a tribe of Dingling origin named Dubo in the eastern Sayans. This name is recognized as being associated with the Tuvan people and is the earliest written record of them. The Xianbei defeated the Xiongnu and they in turn were defeated by the Rouran. From around the end of the 6th century, the Göktürks held dominion over Tuva up until the 8th century when the Uyghurs took over.

The indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Tuva Republic are a Turkic-speaking people of South Siberia, whose language shows strong Samoyedic and Mongolian influences.[2] The name "Tuva" probably derives from a Samoyedic tribe, referred to in 7th-century Chinese sources as Dubo or Tupo, who lived in the upper Yenisei region. These people were known to the Chinese and Mongolians as Uriankhai. Most scholarly opinion seeks the name in the Uriankhai of northern Manchuria, a Jurched people who as a result of extensive migrations gave their name to several peoples living in the region from east Siberia and Manchuria to the Altai mountains.[3] They are to be distinguished from the Altai Uriankhai (ethnic Mongolians living in western Mongolia), the Altainor Uriankhai (a Turkic-speaking people in the Altai Republic within the Russian Federation), and the Khovsgolnor Uriankhai (reindeer herders in the eastern Tuva Republic).

Tuvans were subjects of the Uyghur Khanate during the 8th and 9th centuries. The Uyghurs established several fortifications within Tuva as a means of subduing the population. Uyghur dominance was broken by the Yeniseian Kyrgyz in 840 AD, who came from the upper reaches of the Yenisei.

Mongol rule

In 1207, the Oirat prince Quduqa-Beki led Mongol detachments under Jochi to a tributary of the Kaa-Khem river. They encountered the Tuvan Keshdims, Baits, and Teleks. This was the beginning of Mongol suzerainty over the Tuvans. Tuvans came to be ruled for most of the 17th century by the Khalka Mongol leader Sholoi Ubashi's Altyn-Khan Khanate.

The state of the Altyn-Khan disappeared due to constant warring between the Oirats and the Khalka of Jasaghtu Khan Aimak. The Tuvans became part of the Dzungarian state ruled by the Oirats. The Dzungars ruled over all the Sayano-Altay Plateau until 1755.

The historic region of Tannu Uriankhai, of which Tuva is a part, was controlled by the Mongols from 1207 to 1757, when it was brought under Manchu rule (Qing Dynasty, the last dynasty of China) until 1911.

It then came under the dominion of the Yuan Dynasty in China (1279-1368), and with the fall of the Yuan it was controlled by the Oirots (western Mongolians, also known as Zungars until the end of the 16th and early 17th centuries.[4] Thereafter, the history of western Mongolia, and by extension Tannu Uriankhai (more as a spectator than as a participant), is a story of the complex military relations between the Altan Khanate (Khotogoit tribe) and the Oirots, both competing for supremacy in western Mongolia.[5] The territory of current Tuva has been ruled by the Mongolic Xianbei state (93-234), Rouran Khaganate (330-555), Mongol Empire (1206-1368), Northern Yuan (1368-1691) and Zunghar Khanate (1634-1758).

Qing rule

The Qing dynasty established its dominion over Mongolia as a result of intervening in a war between the Oirots and the Khalkhas, the dominant tribe in the eastern half of Mongolia. In 1691 the Emperor Kangxi accepted the submission of the Khalkhas at Dolon Nor in Inner Mongolia, and then personally led an army into Mongolia, defeating the Oirots near Ulaanbaatar (the capital of present-day Mongolia] in 1696. Mongolia was now part of the Qing state. Qing rule over Tuva came more peacefully, not by conquest but by threat: In 1726 the Emperor Yongzheng ordered the Khotogoit Khan Buuvei Beise to accompany a high Qing official ("amban") to "inform the Uriankhais of [Qing] edicts" in order to prevent "something untoward from happening." [6] The Uriankhais appear to have accepted this arrangement without dispute, at least none is recorded. Qing subjugation of the Altai Uriankhai and the Altainor Uriankhai occurred later, in 1754, as part of a broader military offensive against the Oirots.

Tannu Uriankhai

The Tannu Uriankhai were reorganized into an administrative system similar to that of Mongolia, with five khoshuns ("banner") and 46 or 47 sumuns ("arrow") (Chinese and Russian sources differ on the number of khoshuns and sumuns). Each khoshun was governed by an hereditary prince nominally appointed by the Qing military governor at Uliastai. In the latter half of the 18th century, one of the khoshun princes was placed in charge of the others as governor ("amban-noyon") in recognition of his military service to the dynasty.

Tannu Uriankhai (as well as Altai and Altainor Uriankhai) occupied a unique position in the Qing Dynasty’s frontier administration system. If Qing statutes rigorously defined procedures to be followed by the nobles of Outer and Inner Mongolia, Zungaria, and Qinghai for rendering tribute, receiving government stipends, and participating in imperial audiences, they are silent regarding Tannu Uriankhai.[7] After the demarcation of the Sino-Russian border by the Treaty of Kyakhta (1727), the Qing inexplicably placed border guards ("yurt pickets," Mongolian: ger kharuul) south of the Tannu-ola Mountains separating Tannu Uriankai from Outer Mongolia, not along the Sayan Mountains separating the region from Russia. (This fact was used by 19th-century Russian polemicists, and later Soviet writers, to prove that Tuva had historically been "disputed" territory between Russia and China.) The Qing military governor at Uliastiai, on his triennial inspection tours of the 24 pickets under his direct supervision, never crossed the Tannu-ola mountains to visit Uriankhai. When problems occurred meriting official attention, the military governor would send a Mongol from his staff rather than attend to the matter himself.[7]

Indeed, there is no evidence that Tannu Uriankhai was ever visited by a senior Qing official (except perhaps in 1726). Chinese merchants were forbidden to cross the pickets, a law not lifted until the turn of the 20th century. Instead, a few days were set aside for trade at Uliastai when Uriankhai nobles delivered their annual fur tribute to the military governor and received their salaries and other imperial gifts (primarily bolts of satin and cotton cloth) from the emperor.[8] Thus, Tannu Uriankhai enjoyed a degree of political and cultural autonomy unequalled on the Chinese frontier.[7]

Russian colonists

During the 19th century, Russians began to settle in Tuva, resulting in an 1860 Chinese-Russian treaty, in which the Qing Dynasty allowed Russians to settle providing that they lived in boats or tents. Russian gold prospectors came as early as 1838 to mine gold from the upper Systyg-Khem.[9] In the following decades, gold mining was to be found on the Khüt, Öök, Serlig, and northern tributaries of the Bii-Khem and Ulug-Khem. By 1885, almost 9,000 kilograms of gold had been extracted.[9]

In 1881 Russians were allowed to live in permanent buildings. By that time a sizeable Russian community had been established, whose affairs were managed by an official in Russia. (These officials also settled disputes and checked on Tuvan chiefs.) By 1883 the total number of Russian miners had reached 485.[10]

Russian merchants from Minusinsk followed, especially after the Treaty of Peking in 1860, which opened China to foreign trade. They were lured by the "wild prices," as one 19th-century Russian writer described them, that Tuvans were willing to pay for Russian manufactured goods—cloth, haberdashery, samovars, knives, tobacco, etc. By the end of the 1860s there were already sixteen commercial "establishments" (zavedenie) in Tannu Uriankhai.[11] The Tuvans paid for these goods in livestock-on-the-hoof, furs, and animal skins (sheep, goat, horse, and cattle). But crossing the Sayan Mountains was a journey not without hardships, and even peril; thus, by 1880-85 there were perhaps no more than 50 (or fewer) Russian traders operating in Tannu Uriankhai during the summer, when trade was most active.[7]

Russian colonization followed. It started in 1856 with a sect of Old Believers called the "Seekers of White Waters," a place which according to their tradition was isolated from the rest of the world by impassable mountains and forests, where they could obtain refuge from government authorities and where the Nikon rites of the Russian Orthodox Church were not practiced.[12] In the 1860s a different kind of refugee arrived, those fleeing from penal servitude in Siberia. More Russians came. Small settlements were formed in the northern and central parts of Tuva.

The formal beginning of Russian colonization in Tannu Uriankhai occurred in 1885, when a merchant received permission from the Governor-General of Irkutsk to farm at present-day Turan. Other settlements were formed, and by the first decade of the 20th century there were perhaps 2,000 merchants and colonists.[13]

By the late 1870s and in the 1880s the Russian presence had acquired a political content. In 1878 Russians discovered gold in eastern Uriankhai. There were rumors of fabulous wealth to be gained from this area, and the Russian provincial authorities at Yeniseisk were deluged with petitions from gold miners to mine (permission was granted). Merchants and miners petitioned the Russian authorities for military and police protection.[10] In 1886 the Usinsk Frontier Superintendent was established, its primary function to represent Russian interests in Tannu-Uriankhai with Tuvan nobles (not Qing officials) and to issue passports to Russians traveling in Uriankhai. Over the years this office was to quietly but steadily claim the power of government over at least the Russians in the region—taxation, policing, administration, and justice—powers that should have belonged to, but were effectively relinquished by, the Qing.[12] Shortly after the office of Superintendent was created, the "Sibirskaya gazeta" brought out a special edition, congratulating the government on its creation, and predicting that all Tannu Uriankhai would someday become part of the Russian state.[10]

As a general observation, the Tsarist government had been reluctant to act precipitously in Uriankhai for fear of arousing the Qing. It generally preferred a less obvious approach, one that depended on colonization (encouraged quietly) rather than military action. And it is this that fundamentally distinguished ultimate Russian dominion over Tannu Uriankhai from that of Outer Mongolia, with which it has often been compared. In the former, the Russians were essentially colonists; in the latter, they were traders. The Russians built permanent farm houses in Uriankhai, opened land for cultivation, erected fences, and raised livestock. They were there to stay. What gave the Russian presence added durability was its concentration in the northern and central parts of Tannu Uriankhai, areas sparsely populated by the natives themselves. It was Russian colonization, therefore, rather than purposeful Tsarist aggression, that resulted in Tannu Uriankhai ultimately becoming part of Russia in the following century.

Qing reaction

The Qing government was not oblivious to the Russian presence. In the 1860s and 1870s the Uliastai military governor on a number of occasions reported to Peking on the movement of Russians into Uriankhai.[14] Its suspicions were further aroused by other events. At negotiations between it and Russia resulting in the Tarbagatai Protocol of 1864, which defined a part of the Sino-Russian border, the Russian representative insisted that all territory to the north of the Qing frontier pickets fall to Russia. Moreover, the Uliastai military governor obtained a Russian map showing the Tannu-ola Mountains as the Sino-Russian border.[15]

But in the second half of the 19th century the Qing government was far too distracted by internal problems to deal with this. Instead, it was left to local officials on the frontier to manage the Russians as best they could, an impossible task without funds or troops. The military governors at Uliastai had to be content with limp protests and inconclusive investigations.

End of Qing rule

By the early 20th century the Uriankhai economy had seriously deteriorated, resulting in the increasing poverty of its people. The causes were varied: declining number of fur-bearing animals probably due to over-hunting by both Uriankhais and Russians; declining number of livestock as a result of the export market to Siberia; and periodic natural disasters (especially droughts and plagues), which took a fearful toll on livestock herds.

There was another reason. Uriankhai trade with Russians was conducted on credit using a complex system of valuation principally pegged to squirrel skins. As the number of squirrels declined because of over-hunting, the price of goods increased. The Russians also manipulated the trade by encouraging credit purchases at usurious rates of interest. If repayment were not forthcoming, Russian merchants would drive off the livestock either of the debtor or his relatives or friends. This resulted in retaliatory raids by the Uriankhai.

The situation worsened when the Chinese came. Although the Qing had been successful in keeping Chinese traders out of Uriankhai (unlike in Mongolia and other parts of the frontier), in 1902 they were allowed the cross the border to counter Russian domination of the Uriankhai economy. By 1910 there were 30 or so shops, all branches of Chinese firms operating in Uliastai. For a host of reasons—more aggressive selling, easier credit terms, cheaper and more popular goods for sale—the Chinese were soon able to dominate commerce just as they had in Mongolia. Soon, the Uriankhais, commoners and princes alike, had accumulated large debts to the Chinese.[16]

The end of Qing rule in Tannu Uriankhai came quickly. On 10 October 1911 the revolution to overthrow the Qing broke out in China, and soon afterwards Chinese provinces followed one another in declaring their independence. The Outer Mongolians declared their own independence of China on 1 December and expelled the Qing viceroy four days later.[17] In the second half of December bands of Uriankhai began plundering and burning Chinese shops.

Uriankhai nobles were divided on their course of political action. The Uriankhai governor (amban-noyon), Gombo-Dorzhu, advocated becoming a protectorate of Russia, hoping that the Russians in turn would appoint him governor of Uriankhai. But the princes of two other khoshuns preferred to submit to the new Outer Mongolian state under the theocratic rule of the Jebstundamba Khutukhtu of Urga.[18]

Undeterred, Gombu-Dorzhu sent a petition to the Frontier Superintendent at Usinsk stating that he had been chosen as leader of the independent Tannu Uriankhai state. He asked for protection, and proposed that Russian troops be sent immediately into the country to prevent China from restoring its rule over the region. There was no reply—three months earlier the Tsarist Council of Ministers had already decided on a policy of gradual, cautious absorption of Uriankhai by encouraging Russian colonization. Precipitous action by Russia, the Council feared, might provoke China.[19]

This position changed, however, as a result of genuine concern for the safety of Russian lives and property in Uriankhai, pressure from commercial circles in Russia for a more activist approach, and a petition from two Uriankhai khoshuns in the fall of 1913 requesting to be accepted as a part of Russia. Other Uriankhai khoshuns soon followed suit. In April 1914 Tannu Uriankhai was formally accepted as a protectorate of Russia.[20]

Russian interests in Tuva continued into the twentieth century.

Annexation to Czarist Russia

During the 1911 revolution in China, tsarist Russia formed a separatist movement among the Tuvans. Tsar Nicholas II ordered Russian troops into Tuva in 1912, as Russian settlers were allegedly being attacked. Tuva became nominally independent as the Urjanchai Republic before being brought under Russian protectorate. The Uryankhay Kray joined the Yeniseysk Governorate under Tsar Nicholas II on 17 April 1914. This move was apparently requested by a number of prominent Tuvans, including the High Lama, although it is possible they were actually acting under the coercion of Russian soldiers. A Tuvan capital was established, called Belotsarsk (Белоца́рск; literally, "Town of White Tsar"). Meanwhile, in 1911, Mongolia became independent, though under Russian protection.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 which ended the imperial autocracy, most of Tuva was occupied from 5 July 1918 to 15 July 1919 by Aleksandr Kolchak's "White" Russian troops. Pyotr Ivanovich Turchaninov was named governor of the territory. In the autumn of 1918 the southwestern part was occupied by Chinese troops and the southern part by Mongol troops led by Khatanbaatar Magsarjav.

Independence

From July 1919 to February 1920 the communist Red Army controlled Tuva, but from 19 February 1920 to June 1921 it was occupied by China (governor was Yan Shichao [traditional, Wade–Giles transliteration: Yan Shi-chao]). On 14 August 1921 the Bolsheviks (supported by Russia) established a Tuvan People's Republic, popularly called Tannu-Tuva. In 1926, the capital (Belotsarsk; Khem-Beldyr since 1918) was renamed Kyzyl, meaning "Red"). Tuva was de jure an independent state between the World Wars.

The state's first ruler, Prime Minister Donduk, sought to strengthen ties with Mongolia and establish Buddhism as the state religion. This unsettled the Kremlin, which orchestrated a coup carried out in 1929 by five young Tuvan graduates of Moscow's Communist University of the Toilers of the East. In 1930 the pro-Soviet region began to reform the writing system, first replacing Mongol script with a Latin script, then adopting a Cyrillic script in 1943. Under the leadership of Party Secretary Salchak Toka, ethnic Russians were granted full citizenship rights and Buddhist and Mongol influences on the Tuvan state and society were systematically reduced.[21]

In World War II the state contributed infantry, armored, and cavalry troops to fight against Germany. Under Soviet command a number of units distinguished themselves and received Tuvan medals.[22]

Annexation to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union annexed Tuva outright in 1944, apparently with the approval of Tuva's Little Khural (parliament), though there was no Tuva-wide vote on the issue. The exact circumstances surrounding Tannu-Tuva's incorporation into the USSR in 1944 remain obscure. Salchak Toka, the leader of Tuvan communists, was given the title of First Secretary of the Tuvan Communist Party, and became the de facto ruler of Tuva until his death in 1973. Tuva was made the Tuvan Autonomous Oblast and then became the Tuva ASSR on 10 October 1961. The Soviet Union kept Tuva closed to the outside world for nearly fifty years.

Modern history

In February 1990, the Tuvan Democratic Movement was founded by Kaadyr-ool Bicheldei, a philologist at Kyzyl University. The party aimed to provide jobs and housing (both were in short supply), and also to improve the status of Tuvan language and culture. Later on in the year there was a wave of attacks against Tuva's sizeable Russian community, resulting in 88 deaths. Russian troops eventually were called in. Many Russians moved out of the republic during this period. To this day, Tuva remains remote and difficult to access.[23]

Tuva was a signatory to the 31 March 1992 treaty that created the Russian Federation. A new constitution for the republic was drawn up on 22 October 1993. This created a 32-member parliament (Supreme Khural) and a Grand Khural, which is responsible for foreign policy and any possible changes to the constitution, and ensures that Tuvan law is given precedence. The constitution also allowed for a referendum if Tuva ever sought independence. This constitution was passed by 53.9% (or 62.2%, according to source) of Tuvans in a referendum on 12 December 1993.[24]

References

- ↑ Potapov L.P., 1969, "Ethnic composition and origin of Altaians. Historical ethnographical essay", p. 88

- ↑ Karl Menges, Die sibirischen Türksprachen [The Siberian Turkic Languages] in Handbuch der Orientalistic, (Leiden/Cologne, 1963), v. 5, pp. 73-74.

- ↑ Helmut Welhelm, A Note on the Migration of the Urianghai, in Ural-Altaische Bibliothek, (Wiesbaden, 1957), v. 4, pp. 172-75.

- ↑ Iakinf (Bichurin), Sobranie svedenii o narodakh obitgavsikh v srednei Asii v drevniya vremena [Collected Information on the Peoples of Central Asia] (St. Petersburg, 1851), v. 1, p. 439; M.G. Levin and L.P. Potapov, The Peoples of Siberia (Chicago and London, 1961), pp. 382-83.

- ↑ For a history of this period, see Ewing, The Forgotten Frontier, pp. 176-184.

- ↑ Chi Yunshi, comp., Huangchao fanbu yaolue [Essential Information Regarding the Imperial Dependencies on the Frontier], (1845; rpr. Taipei 1966), v. 1, p. 213.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Thomas E. Ewing, The Forgotten Frontier: South Siberia (Tuva) in Chinese and Russian History, 1600-1920, Central Asiatic Journal (1981), v. XXV, p. 176.

- ↑ Yang Jialo, ed., Zhongguo jingchi shiliao [Sources on the Economic History of China] (Taipei, 1977), p. 447.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mänchen-Helfen, Otto (1931). Journey to Tuva. Los Angeles: Ethnographics Press, University of Southern California. ISBN 1-878986-04-X.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 V.I. Dulov, Russko-tuvinskie ekonomicheskie svyazi v. XIX stoletii, [Russian-Tuvin economic relations in the 19th century] in Uchenye zapiski tuvinskogo nauchno-issledovatel’skogo instituta yazyka, literatury I istorii (Kyzyl, 1954), no. 2, p. 104.

- ↑ V.M. Rodevich, Ocherki Uriankhaiskogo kraya [Essays on the Uriankhai Region] (St. Petersburg, 1910), p. 104.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 F.Ya. Kon, Usinskii krai [Usinsk Region] (Krasnoyarsk 1914) pp. 29-38.

- ↑ V.L. Popov, "Vtoroe puteshestvie v Mongoliyu, [Two Travels to Mongolia], (Irkutsk 1910) p. 12.

- ↑ Qingdai chouban iwu shimo [Complete Records of the Management of Barbarian Affairs] (Peiping, 1930), Xienfeng 5:30b.

- ↑ Liu Jinzao, ed., Qingchao xu wenxien tongkao [Encyclopedia of the Historical Records of the Qing Dynasty, Continued] (Shanghai, 1935; repr. Taipei, 1966), pp. 10, 828-30.

- ↑ M.I. Bogolepov, M.N. Sobolev, Ocherki russko-mongol’skoi torgovli [Essays on Russian-Mongolian Commerce] (Tomsk 1911), p. 42.

- ↑ Thomas E. Ewing, Revolution on the Chinese Frontier: Outer Mongolia in 1911, Journal of Asian History (1978), v. 12., pp. 101-19.

- ↑ L. Dendev, Mongolyn tovch tüükh [Brief History of Mongolia] (Ulan Bator, 1934), p. 55.

- ↑ N.P. Leonov, Tannu Tuva (Moscow, 1927), p. 42.

- ↑ Istoriya Tuvy [History of Tuva], v. 1, pp. 354-55.

- ↑ Tuva: Russia's Tibet or the Next Lithuania?

- ↑ Medals of the Second World War, TUVINIAN ARAT REPUBLIC

- ↑ "Tuva and Sayan Mountains". Geographic Bureau — Siberia and Pacific. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ Reuters News, 16 Dec, 1993 ”Tuva republic approves own constitution” or BBC Monitoring Service, 15 Dec, 1993 “Figures from Ingushetia, Tyva, Yaroslavl and parts of Urals and Siberia”

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||