History of Toulouse

The history of Toulouse, in Midi-Pyrénées, southern France, can be traced back to ancient times. It was the capital of the County of Toulouse in the Middle Ages and today is the capital of the Midi-Pyrénées region.

Before 118 BC: pre-Roman times

Archaeological evidence dates human settlement in Toulouse to the 8th century BC. The location was very advantageous, at a place where the Garonne River bends westward toward the Atlantic Ocean and can be crossed easily. People gathered on the hills overlooking the river, 9 kilometers south of today's downtown Toulouse. Immediately north of these hills is a large plain suitable for agriculture. The site was a focal point for trade between the Pyrenees, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. The early name of the city was Tolosa. Researchers today agree that the name is probably Aquitanian, related to the old Basque language, but the meaning is unknown. The name of the city has remained almost unchanged over centuries--rare among French cities--despite Celtic, Roman and Germanic invasions.

The first inhabitants seem to have been Aquitanians, of whom little is known. Later came Iberians from the south, who, like the Aquitanians, were non-Indo-European people. In the 3rd century BC there came a Celtic Gallic tribe called the Volcae Tectosages from Belgium or southern Germany, the first Indo-European people to appear in the region. They settled in Tolosa and interbred with the local people. Their Gaulish language became predominant. By 200 BC Tolosa is attested to be the capital of the Volcae Tectosages (coins found), which Julius Caesar later called Tolosates (singular Tolosas) in his famous account of the Gallic wars (De Bello Gallico, 1.10). Archaeologists say Tolosa was one of the most important cities in Gaul, and certainly it was famed in pre-Roman times for being the wealthiest one. There were many gold and silver mines nearby, and the offerings to the holy shrines and temples in Tolosa had accumulated a tremendous wealth in the city.

118 BC–AD 418: Roman period

The Romans started their conquest of southern Gaul (later known as the Provincia) in 125 BC. Moving westward, they founded in 118 BC the colony of Narbo Martius (Narbonne), the Mediterranean city nearest to inland Toulouse, and so they came into contact with the Tolosates, famous for their wealth and the key position of their capital for trade with the Atlantic. Tolosa chose to ally with the daunting Romans, who established a military fort in the plain north of the city, a key position near the border of independent Aquitania, but otherwise left the inhabitants of Tolosa free to rule themselves in semi-independence.

In 109 BC a Germanic tribe, the Cimbri, descending the Rhône Valley, invaded the Provincia and defeated the Romans, whose power was shaken all along the recently conquered Mediterranean coast. The Tolosates rebelled against Rome and murdered the Roman garrison. Soon, however, Rome recovered and defeated the invaders. In 106 BC, General Q. Servilius Caepio was sent to reconquer and punish Tolosa. With the help of some Tolosates who remained faithful to Rome, he captured the city and the immense wealth of the temples and shrines.

Tolosa was then fully incorporated into the Roman Provincia (Provincia Romana—the usual name for what was officially called the province of Transalpine Gaul, with its capital at Narbo Martius). Tolosa was an important military garrison at the western border of the Roman realm. However the city remained a backwater in the Provincia, people were still living in the old Celtic city in the hills. No Roman colony was established; few Roman soldiers settled in the area.

Things changed after the conquest of the rest of Gaul by Julius Caesar. In a sign that Romanization of the people was already well under its way, Tolosa did not take part in the various uprisings against Rome during the Gallic wars. In fact southern France would prove to be the most romanized part of France after the fall of the Roman Empire. Caesar established his camp in the plain of Tolosa in 52 BC, and from there he conquered the western regions of Aquitania. With the conquest of Aquitania and the whole of Gaul, Tolosa was no more a military outpost. It capitalized on its key position for trade between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, now both under Roman control, and the city developed rapidly.

Consequently, the most important event in the history of Toulouse was the decision to relocate the city north of the hills. A typical Roman city of straight streets was founded in the plain on the eastern bank of the river sometime at the end of the reign of Augustus and the start of the reign of Tiberius (around AD 10 –AD 30). The population was forced to relocate to the new city, still named Tolosa, while the old settlement was abandoned. Walls were built around the new city, probably at the initiative of Emperor Augustus, who wanted to create a major city at the junction of the newly built Via Aquitania and the Garonne River. Due to the Pax Romana, walls were not needed around cities, and they were only built as an imperial favor to show the special status of a city. Until the fall of the Roman Empire, the new Tolosa was to be a civitas of the province of Gallia Narbonensis (capital Narbo Martius – Narbonne), the new name of the old Provincia.

With imperial favor and a thriving trade, Tolosa rapidly transformed into one of the major cities of the Roman Empire. During the civil war following Nero's death, Tolosa native M. Antonius Primus led the armies of Vespasian into Italy and entered Rome in AD 69, establishing the Flavian dynasty. Emperor Domitian, son of Vespasian and personal friend of M. Antonius Primus, granted Tolosa the honorific status of Roman colony. Another sign of imperial favor was displayed when Domitian gave Tolosa the title of Palladia, in reference to Pallas Athena, goddess of arts and knowledge, of whom he was very fond.

Palladia Tolosa was by all means a major Roman city, with aqueducts, circus and theaters, thermae, a forum, an extensive sewage system, etc. Protected by its walls and by its far location from the Rhine border, Palladia Tolosa escaped unscathed from the invasions of the 3rd century. With much of Gaul destroyed, Toulouse emerged as the fourth largest city of the western half of the Roman Empire, after Rome, Treves and Arles. Around that time Christianity entered the city, and the Christian community greatly expanded under the first bishop of Toulouse Saint Saturnin (locally known as Saint Sernin), who was martyred in Toulouse around AD 250. In 313 the Edict of Milan established religious freedom in the empire, ending persecution of Christianity. In 403 the Saint-Sernin basilica was opened to serve as a shrine for the relics of Saint Saturnin.

On December 31, 406 the Rhine frontier was breached by a massive invasion of tribes seeking to escape starvation during a brutal winter. In 407 Toulouse was besieged by the Vandals, but under the impulse of its bishop Saint Exuperius the city resisted behind its strong walls, and the Vandals lifted the siege and moved into Spain, and from there into North Africa where they settled. "The provinces of Aquitaine and of the Novempopulana (that is, Gascony), of Lyon and of Narbonne are, with the exception of a few cities, one universal scene of desolation. And those which the sword spares without, famine ravages within. I cannot speak without tears of Toulouse which has been kept from failing hitherto by the merits of its reverend bishop Exuperius." wrote Jerome to a Roman widow in 409 (Letters cxxiii.16 ). In 413, three years after they had sacked Rome, the Visigoths under King Ataulf captured Toulouse. Under pressure from Roman forces, they soon withdrew south of the Pyrenees. After the murder of Ataulf, his successor Wallia resolved to make peace with Rome. In exchange for peace, in 418, Emperor Honorius granted the Visigoths the region of Aquitania as well as the city of Toulouse (in Gallia Narbonensis at the border of Aquitania). The Visigoths chose the prestigious and wealthy Palladia Tolosa as the capital of their kingdom, thus ending Roman rule in Toulouse.

418–508: Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse

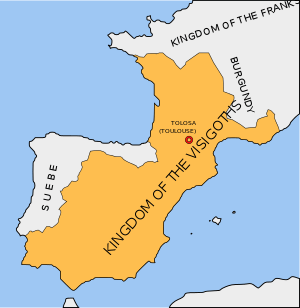

The Visigothic kings of Toulouse, officially one of the foederati (federated allies) of the Roman Empire of the West and limited to Aquitania and Toulouse, soon started to encroach on neighboring territories. As allies of Rome, the Visigoths helped defeat various Germanic invaders in Spain, notably the Suebi, and took advantage of their position to expand their own territory south of the Pyrenees. They tried to conquer the Mediterranean coast of the remaining province of Gallia Narbonensis but were opposed by their Roman ally. In 439 the Roman general Litorius defeated the Visigoths at Narbonne and even succeeded in driving them back to Toulouse. He besieged the city, but was defeated and taken prisoner in a battle outside the city. Avitus, the praetorian prefect of Gaul, who had great influence with King Theodoric I of the Visigoths, was then sent to Toulouse and brought about the conclusion of peace. In 451, under threat of a major invasion of the Huns in Gaul, Avitus again negotiated a treaty between Rome and the Visigoths, and they jointly defeated the Huns. In 455, Avitus, then magister militum (the senior military officer of the Empire) on a diplomatic mission to King Theodoric II of the Visigoths, was proclaimed the new Roman emperor in Toulouse by his Visigothic friends as the news arrived that the Vandals had sacked Rome and that Emperor Petronius Maximus had been murdered. However, his reign in Rome was brief, and he was defeated by his enemies in 456. This antagonized the Visigoths and pushed them into constant warfare with the new Roman leaders. Eventually, a weaker and weaker Rome gave way. The region of Narbonne was finally conquered by the Visigoths in 462.

King Euric of the Visigoths (466–484) was the most adamant enemy of Rome, and he was very successful in extending the Visigothic territory in Gaul and Spain. In 475 he officially broke the treaty with Rome and proclaimed full independence, one year before the Western Roman Empire was to disappear. Toulouse was now the capital of a rapidly expanding Gothic kingdom. By the end of the 5th century, the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse extended from the Loire Valley in the north to the Strait of Gibraltar in the south, and from the Rhône in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. This was the largest extent of land ever to be controlled from a capital at Toulouse.

Unlike most cities in western Europe, Toulouse remained prosperous throughout the period of the Migrations (also known as Great Invasions). Although the Visigoths professed a non-Trinitarian brand of Christianity known as Arianism, and lived segregated from their Gallo-Roman subjects, they were generally well accepted by their subjects, to whom they brought protection and continued prosperity. The city behind its 1st-century walls continued to encompass the same area, whereas most cities of western Europe were hastily building new walls enclosing only a small portion of their former Imperial area. The treasure which the Visigoths seized in Rome in 410 (including the treasure of the Temple in Jerusalem) is said to have been stored in Toulouse at the time. The Visigoths slowly achieved a blend of the Roman and Gothic cultures. They are responsible for the preservation of Roman law through the drafting of the Breviary of Alaric in 506 which applied on this immense territory both to the Visigoths and the local Roman populations. By all accounts, the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse was more Romanized and its state structure more elaborated than the Frankish kingdom north of the Loire Valley.

However, the pagan Franks under their king Clovis converted to Catholicism, and thus received the considerable support of the network of Christian bishops, rapidly becoming the only effective institution of power that was more than local in extent, which strongly opposed the Arianism of the Visigothic aristocrats. Soon enough, the Franks on their march south came into contact with the northern borders of the Visigothic kingdom. War ensued, and eventually the Visigothic king Alaric II was defeated by the Frankish king Clovis at the Battle of Vouillé in 507, a battle important in the psyche of modern-day France (etymologically land of the Franks), where Franks are perceived as "French" and Visigoths have become "foreigners". Following their victory, the Franks moved south, conquered Aquitania, and captured Toulouse in 508. The Visigoths withdrew to their Hispanic dominions, where they later resettled their capital in Toledo. Toulouse became part of Aquitaine— cut from Narbonne and the Mediterranean region where Visigothic rule remained—a diminished capital city within the scarcely integrated Frankish kingdom.

508–768: Merovingian Franks and the duchy of Aquitaine

Following the Frankish conquest, Toulouse entered a period of decline and anarchy. Bad weather, plagues, demographic collapse, decline of schools, education and culture were common features of the Frankish lands in the dark period of the 6th and 7th centuries. Following Clovis' death in 511, Aquitaine was divided between his sons (the Merovingian dynasty) like the rest of the kingdom. The period was extremely complex, with each Merovingian king fighting and murdering each other for the control of the whole of the Frankish realm, which was reunited, then divided again, then reunited, etc. Far from the power base of the Franks, Aquitaine was loosely controlled by one or the other competing Frankish kings, who delegated dukes to control the region in their name. In 680, the Duchy of Vasconia (founded 602) and Aquitaine merged by personal union under the first independent duke of Aquitaine Felix, a patrician of 'Roman' stock from Toulouse. The Merovingian monarchy was so weakened that a local independent dynasty of dukes emerged in Aquitaine. Whether they were blood relatives of the Merovingians, Frankish envoys turned dynastic rulers or local non-Frankish rulers is still a matter of debate. Although not recognized by the Merovingians, they governed as kings in all but name in Aquitaine (including the then Basque speaking area of Gascony south of the Garonne River), and their capital was in Toulouse.

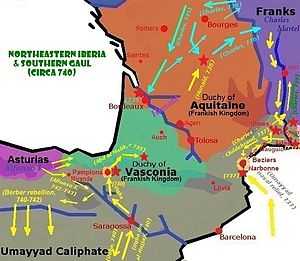

At the beginning of the 8th century, the Arabs appeared in the region. Coming from Spain along the Mediterranean coast they captured Narbonne from the last Visigoths in 719. Then al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, the wali (governor) of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), mustered a strong army (from North Africa, Syria, and Yemen) and set to conquer Aquitaine. Moving west from Narbonne he besieged Toulouse, capital of the duchy of Aquitaine, but after 3 months of siege, just as the city was about to surrender, Duke Odo of Aquitaine (also known as Eudes) who had left the city to find help managed to come back with an army and defeated the Arab army at the Battle of Toulouse on June 9, 721, just outside of the city walls. Noticeably, the Frankish Charles Martel had refused to help, wishing to take advantage of the situation to recover Aquitaine, and Odo is recorded as leading an army of ('Roman' and maybe Basque speaking Gascon) Aquitanians and regional Franks to fight against the Arabs. The Battle of Toulouse was a crushing defeat for the Arabs, who perished in battle by the thousands. The Arab army scattered and most of the soldiers were killed, al-Samh died of his wounds, and the remainder of the Arab troops under second-in-command Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi fled back to Narbonne where Duke Odo decided not to pursue them. This battle is still remembered today among Arab historians as the major check in Arab expansions toward the west.

Sometime before 730, Odo decided to ally with the Muslim ruler of Catalonia, Uthman ibn Naissa (also known as Munuza). The greatest threat to Duke Odo was his Frankish neighbor on the north. Odo married his daughter to Munuza, and Arab raids in Aquitaine temporarily ended, thus enabling Odo to focus on the northern threat. However, in 731 Munuza rebelled against the new wali of al-Andalus, Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi. Abd al-Rahman soon defeated Munuza, and in order to punish Duke Odo for his alliance with Munuza he launched a raid in Aquitaine. With the memory of the Battle of Toulouse looming ominously in his mind, he chose to cross the Pyrenees west of Toulouse, rather than coming from Narbonne, and soon he reached Bordeaux where he defeated Duke Odo's army. Odo seems to have disbanded some of his troops after the peace signed with Munuza, which could account for his failure to stop Abd al-Rahman. With Bordeaux captured, the Arabs set north towards the sacred Frankish abbey of Tours. Odo had no choice but to ask for Frankish help. Charles Martel, then leader of the Franks (Merovingian kings were maintained as puppet kings), finally preoccupied by the Arab threat moving to his land, mustered an army and met the Arabs near Poitiers. On 25 October 732, at the most celebrated Battle of Poitiers, the Arabs were defeated and Abd al-Rahman died on the field. The scholars of Charlemagne, grandson of Charles Martel, made much for the renown of the Battle of Poitiers. In Europe it is still remembered as "the" battle which saved Europe and Christendom from the Arabs.

Following the Battle of Poitiers, Duke Odo was forced to do homage to Charles Martel and recognize the overlordship of the Franks. However, the Franks were busy in Burgundy and did not pursue further south, leaving Odo virtually independent until his death in 735. He was succeeded by his son Duke Hunald of Aquitaine (also known as Hunold, or Hunaud). Hunald refused to recognize the authority of Charles Martel, and this time Charles Martel sent his troops south and captured Bordeaux in 736. Hunald was forced to accept Frankish overlordship, and Charles Martel withdrew his troops from Aquitaine in order to attack the Arab territories on the Mediterranean coast around Narbonne. In 741 Charles Martel died and was followed by his son Pippin the Short (Pépin le Bref). Duke Hunald then rebelled again against Frankish authority in 742, but he was finally defeated in 745 and he retired to a monastery. He was succeeded by his son Duke Waifer of Aquitaine (also known as Waifre, or Gaifier). Pippin, busy at home and also sharing power with his brother, left Waifer in possession of the entirety of Aquitaine, without occupying it. However, in 747 Pippin became the only master of the Frankish realm. In 751 he deposed the last Merovingian king and was elected King of the Franks with the support of the Pope, founding the Carolingian dynasty.

In 752 Pippin resumed the conquest of the Arab territories on the Mediterranean coast where his father had failed. Amidst fierce local resistance, including one intervention of Duke Waifer in the area in 752, it was not until 759 that he finally captured Narbonne and effectively ended Arab rule north of the Pyrenees. Aquitaine was now surrounded by the Frankish kingdom on most sides. In 760, Pippin started the conquest of Aquitaine. It proved a difficult task. It took the Franks eight long years to subdue Aquitaine and Toulouse. Gascony was also submitted. In 768, the last pockets of resistance fell as Duke Waifer was betrayed and murdered in mysterious circumstances. Aquitaine was utterly destroyed after 8 long years of scorched-earth tactics pursued both by Pippin and Waifer. Nonetheless, the region was soon to recover under the long reign of Charlemagne.

768–877: Carolingian Franks and the Kingdom of Aquitaine

Toulouse and Aquitaine (as well as Gascony) were once again part of the kingdom of the Franks. Following his victory, Pippin the Short died in 768 and was followed by his sons Charlemagne and Carloman. With Pippin having died, Hunald, son of the late Duke Waifer, raised an insurrection against Frankish power in Aquitaine. Charlemagne soon intervened and defeated him. In 771, Carloman died and Charlemagne was left as the only ruler of the Frankish realm. In 778, Charlemagne led his army into Spain against the Arabs. On his way back there happened the famous event of Roncesvalles (Roncevaux in French): Charlemagne's rear-guard was attacked in the pass of the same name by some Basque warriors. This led Charlemagne to realize that Frankish power in Gascony and Aquitaine was still feeble, and that the local populations were not entirely loyal to the Franks. Consequently, that same year he completely reorganized the administration of the region: direct Frankish administration was imposed, and Frankish counts (deputies of the Frankish king) were created in key cities, such as Toulouse.

In 781, he set up the Kingdom of Aquitaine, comprising the whole of Aquitaine (including Gascony, formally) plus the Mediterranean coast from Narbonne to Nîmes (area then known as Gothia), and gave the crown of Aquitaine to his three-year-old son Louis. Other such kingdoms were created inside the wider Carolingian empire in places such as Bavaria or Lombardy. They were meant to ensure the loyalty of local populations in territories freshly conquered and with strong local idiosyncrasies. Crowns were given to the sons of Charlemagne. The people of Aquitaine were known in the whole empire for their strong spirit of independence, as well as their wealth. Indeed, the region was quite prosperous during that period, past the recovery from the war of conquest.

Charlemagne in turn saw he could not trust the local nobility of the Vasconia, whose ties and loyalty to the Franks were flimsy. He took to appoint Frankish counts of his trust and create counties (e.g. Fezensac) that could fight the power of regional lords, like the duke Lupus. General supervision of this Basque frontier seems to have been placed in the hands of Chorson, count or duke of Toulouse. These politics displeased the Basques, and in 787 or 789 we learn that Chorson was captured by Odalric "the Basque", probably son of duke Lupus, who forced Chorson to an agreement which Charlemagne considered so shameful that replaced him by the Count William in 790.

The reign of Charlemagne in general saw a great recovery of western Europe after the Dark Ages preceding it, and Toulouse was no exception. Toulouse was a major Carolingian military stronghold in front of Muslim Spain. Military campaigns against the Muslims were launched from Toulouse almost every year during the reign of Charlemagne. Barcelona was conquered in 801, as well as a large part of Catalonia. Together with the northern areas of Aragon and Navarre along the Pyrenees, the region became the southern march (the Spanish March) of the Frankish empire.

In 814, Charlemagne died, and his only surviving son was Louis, king of Aquitaine, who became Emperor Louis the Pious (Louis le Pieux). The Kingdom of Aquitaine was transmitted to Pippin, the second son of Louis the Pious. Gothia was detached from the Kingdom of Aquitaine and administered directly by the emperor, thus recreating the limits of the former duchy of Aquitaine. Problems soon arose. Louis the Pious had three sons, and in 817 he arranged an early allocation of the shares in the future inheritance of the empire: Pippin was confirmed king in Aquitaine (Pippin I of Aquitaine), Louis the German was made king in Bavaria, while the eldest son Lothar was made co-emperor with future authority over his brothers.

In 823, Charles the Bald (Charles le Chauve) was born from the second wife of Louis the Pious. Soon enough, she wished to place her son in the line of succession. Louis the Pious was rather weak, and fight started between the three sons on one side, and their father and his new wife on the other side, which eventually would lead to the total collapse of the Frankish empire. Louis the Pious was toppled from power, then reinstalled, then toppled, then reinstalled again. In 838 Pippin I of Aquitaine died, and Louis the Pious and his wife managed to install Charles the Bald as the new king of Aquitaine. At the Assembly of Worms in 839 the empire was re-divided like this: Charles the Bald was given the western part of the empire, Lothar the central and eastern part, while Louis the German was keeping only Bavaria. Pippin II of Aquitaine, the son of Pippin I, was not going to accept such a decision. He was hailed king by the Aquitanians (but not by the Basques, who by then had seceded and detached Vasconia from Aquitaine), and he resisted his grandfather. Louis the German in Bavaria also opposed the decision of his father.

Eventually Louis the Pious died in 840. Lothar the eldest son claimed the whole empire, general war broke out. First allied with his nephew Pippin II, Louis the German soon allied with his half-brother Charles the Bald and they jointly defeated Lothar. Then in August 843, they signed probably the most important treaty in European history, the Treaty of Verdun. The empire was divided in three: Charles the Bald was given the western part, Francia Occidentalis (Western Frankland, soon to be called France), Louis the German was given the eastern part, Francia Orientalis (Eastern Frankland, soon to become the German Holy Roman Empire), while Lothar was given the central part, soon to be conquered and divided by his two brothers.

The family feud had left the empire weak and undefended. Some invaders rightly analyzed the situation and took advantage of it: the Vikings. Following the Treaty of Verdun, Charles the Bald moved south to defeat Pippin II and add Aquitaine to his territory. First he conquered Gothia over its rebelled count (who had taken advantage of the Carolingian feud) and had him executed. In 844, he set west and was besieging Toulouse, the capital of King Pippin II of Aquitaine. However, he had to withdraw without being able to capture the city. That same year, the Vikings entered the mouth of the Garonne River, took Bordeaux, and sailed up as far as Toulouse, plundering and killing all along the Garonne River valley. They moved back when they reached Toulouse, without attacking the city. It is still a matter of debate among historians whether they were called by Pippin II in his fight against Charles the Bald (as Charles' propaganda later claimed), helped defeat Charles the Bald, and left with due payment from Pippin II, or whether they just took advantage of the war to invade unchecked but moved back at the sight of the strong garrison of Toulouse who had just resisted successfully Charles the Bald.

Following these events, Charles the Bald in 845 signed a treaty with King Pippin II of Aquitaine whereby he recognized him as king of Aquitaine, in exchange of which Pippin II was relinquishing the northern part of Aquitaine (county of Poitiers) to Charles the Bald. However, the Aquitanians grew very unhappy with their king Pippin II, perhaps for his friendliness towards the Vikings who inflicted terrible damage on the population, and so in 848 they called Charles the Bald to topple Pippin II. In 849 Charles the Bald was south again, and he was handed over the capital of Aquitaine, Toulouse, by Frédelon, the count of Toulouse recently appointed by Pippin II. Charles the Bald then officially confirmed Frédelon as count of Toulouse. Soon the whole of Aquitaine was submitting to Charles the Bald, and in 852, Pippin II was made prisoner by the Basques and handed over to his uncle Charles the Bald who put him in a monastery.

In 852, Count Frédelon of Toulouse died, and Charles the Bald appointed Frédelon's brother Raymond (Raimond) as the new count. This was a special favor, normally counts were only administrative agents not chosen in the same family. However, it would prove to be the start of the dynasty of the counts of Toulouse, who were all descendants of Count Raymond I of Toulouse (Raimond I). In 855, following the example of his grandfather Charlemagne, Charles the Bald recreated the kingdom of Aquitaine (without Gothia), and he gave the crown to his son Charles the Child (Charles l'Enfant). Meanwhile, Pippin II of Aquitaine had escaped from his monastery in 854, and he was raising an insurrection in Aquitaine. It did not prove very popular among Aquitanians though, and he was unsuccessful. He then resorted to calling the Vikings for help. In 864, at the head of a Viking army, Pippin II of Aquitaine besieged Toulouse where the count of Toulouse resisted fiercely. The siege failed, and the Vikings left to plunder other areas of Aquitaine. Pippin II, abandoned by all, saw the ruins of his ambitions. He was captured and again put in a monastery by his uncle, where he died soon after.

In 866, Charles the Child died. Charles the Bald then made his other son, Louis the Stammerer (Louis le Bègue), the new king of Aquitaine. By then, the central state in the kingdom of France was rapidly losing authority. Charles the Bald was rather unsuccessful at containing the Vikings, local populations had to rely on their local counts to resist the Vikings, and the counts soon became the main source of authority, challenging the central authority of Charles the Bald in Paris. As they grew in power, they started to be succeeded in the same family and establish local dynasties. Wars between the central power and the counts arose, as well as wars between the competing counts, which further debilitated the defenses against the Vikings. Western Europe, France in particular, were again entering a new dark age, which would prove even more disastrous than the one of the 6th and 7th centuries.

In 877, Charles the Bald had to give in: he signed the Capitulary of Quierzy, which allowed counts to be succeeded by their sons when they died. This was the founding stone of feudalism in western Europe. Charles the Bald died four months later. The new king of France was his son Louis the Stammerer, formally king of Aquitaine. Louis the Stammerer did not choose any of his sons to become the new king of Aquitaine, thus in effect putting an end to the kingdom of Aquitaine, which would never be revived again. Louis the Stammerer died shortly after in 879 and was succeeded by his two sons, Louis III and Carloman. Louis III inherited northwest France, while Carloman inherited Burgundy and Aquitaine. In practice however, during the years 870-890 the central power was so weakened that the counts in southern France achieved complete autonomy. The dynasties they established ruled independently. The central state in Paris would not be able to reassert its authority over the south of France for the next four centuries.

877–10th century

By the end of the 9th century, Toulouse had become the capital of an independent county, the county of Toulouse, ruled by the dynasty founded by Frédelon, who in theory was under the sovereignty of the king of France, but in practice was totally independent. The counts of Toulouse had to fight to maintain their position at first. They were mostly challenged by the dynasty of the counts of Auvergne, ruling over the northeastern part of the former Aquitaine, who claimed the county of Toulouse as their own, and even temporarily ousted the counts of Toulouse from the city of Toulouse. However, in the midst of these Dark Ages, the counts of Toulouse managed to preserve their own, and unlike many local dynasties that disappeared, they achieved survival. Their county was just a small fraction of the former Aquitaine, the southeastern part of it in fact. However, at the death of Count William the Pious of Auvergne (Guillaume le Pieux) in 918 they came into the possession of Gothia which had been in the family of the counts of Auvergne for two generations. Thus they more than doubled their territory, once again reuniting Toulouse with the Mediterranean coast from Narbonne to Nîmes. The county of Toulouse took its definite shape, from Toulouse in the west to the Rhône in the east, a unity that would survive until the French Revolution as the province of Languedoc. Toulouse would never again be part of the Aquitaine polity, whose capital in later times would become Poitiers, then Bordeaux. At first though, the memories of Aquitaine lived strong in Toulouse. Count William the Pious of Auvergne was the first to recreate the title of Duke of Aquitaine for himself in the 890s. Then the count of Poitiers inherited the title in 927. In 932 the king of France Raoul was fighting against the count of Poitiers, and he transferred the title of Duke of Aquitaine to his new ally Count Raymond III Pons of Toulouse (Raimond III). However, the title did not mean much. The various counts of the former Aquitaine were all independents, and did not recognize a superior authority.

Various factions were competing for the throne of France, but since all central authority had disappeared, the position of King of France had become an almost empty title. After Raoul's death, another faction succeeded in establishing an English bred Carolingian prince to the throne, Louis IV from Overseas (Louis IV d'Outremer). Raymond III Pons was from the opposite faction and so when he died in 950 Louis IV awarded the title of Duke of Aquitaine to Count William III Towhead of Poitiers (Guillaume III Tête d'Étoupe) who was an ally of Louis IV. From now on the title of Duke of Aquitaine would be used in the family of the counts of Poitiers, whose power base of Poitou was in the northwestern part of the former Aquitaine. The counts of Toulouse would soon forget any dreams about Aquitaine. Eventually, at the death of the Carolingian king of France Louis V in 987, the Robertian faction succeeded in having its chief, Hugh Capet (Hugues Capet) elected to the French throne. This time, the Carolingian dynasty effectively ended. Hugh Capet was the founder the Capetian dynasty, which would rule in France for the next eight centuries. However, from now on the history of France is irrelevant to Toulouse, at least until the 13th century.

The counts of Toulouse had extended their rule to the Mediterranean coast, but they would not long enjoy the large domain they had succeeded in carving for themselves. The 10th century was perhaps the worst century for western Europe in the last two millennium. Four centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, civilization had declined, arts and education were in a very poor state. There had been momentarily a rebirth of culture and order in the time of Charlemagne, but soon with the return of invasions (especially the Vikings), western Europe was falling again. This conjugated with dramatic civil wars as explained above, as well as bad weather, plagues, population loss. Entire areas of western Europe returned to wilderness. Cities were completely depopulated. Churches were abandoned or plundered, the Church was experiencing a sharp decline in morals. It seemed as if the legacy of the Roman Empire would completely disappear. Culture from the Antiquity only survived in a few scattered monasteries. This was in sharp contrast with the then flourishing emirate of Córdoba in Spain or the Byzantine Empire. Another phenomenon of these times was the complete disappearance of central authority. Power fragmented, falling first in the hands of counts, then viscounts, then in the hands of thousands of local feudal lords. By the end of the 10th century, France was ruled by thousands of local rulers who controlled only one town, or one castle and the few villages around. Toulouse and its county was exactly reflecting this situation. Between 900 and 980 the counts of Toulouse gradually lost control over the county, with the emergence of local dynastic rulers in every part of the county. By the end of the 10th century the counts of Toulouse only had authority over a few estates scattered around the county. Even the city of Toulouse was ruled by a viscount independent from the counts of Toulouse!

Invasions had also returned. The famous ruler of the emirate of Córdoba, Abd al-Rahman III, managed to reunite Muslim Spain, and carried the emirate of Córdoba to its zenith, transforming it into the prestigious caliphate of Córdoba in 929. In the 920s he launched a general offensive against the Christian kingdoms in the north of Spain. In 920 (and possibly also in 929) one of his armies crossed the Pyrenees and went as far north as Toulouse, without capturing the city. In 924, the Magyars (ancestors of the Hungarians) launched an expedition toward the west and went as far as Toulouse, but they were defeated by Count Raymond III Pons of Toulouse. At the end of the 10th century, all the Carolingian wars and subsequent invasions had left the county of Toulouse in disarray. Large expanses of lands were left uncultivated, many farms had been abandoned. Toulouse was perhaps faring a little better than northern France in the sense that its proximity with Muslim Spain meant there was a strong flow of knowledge and culture coming from the schools and printing houses of Córdoba. Toulouse had also retained Roman Law unlike northern France, and had in general kept more of the Roman legacy, even in these troubled times. The ground was there for a recovery of civilization.

11th century

The end of Carolingians marked the beginning of Feudalism.

At the beginning of the millennium, the drifting attitude of the clergy and the confiscation of the Church by the Toulouse administration initiated a degradation of the worship. The Saint-Sernin church, the Daurade basilica and the Saint-Étienne cathedral were not maintained properly. New religious currents appeared, like the Cluniac reform.

Bishop Isarn, helped by Pope Gregory VII, tried to put everything back in order. He gave the Daurade Basilica to the Cluniac abbots in 1077. In Saint-Sernin, he met a strong opposition in the person of Raimond Gayrard, a provost who had just built a hospital for the poor and was proposing to build a basilica.

Supported by count Guilhem IV, Saint Raymond finally gained permission from Pope Urban II to dedicate the building in 1096. The religious quarrels had just awoken the faith of Toulouse. This rebirth was accompanied by a new demographic progression, supported by technically more efficient agriculture.

The suburbs of Saint-Michel and Saint Cyprien were built during this period. The Daurade bridge connected in 1181 the Saint-Cyprien suburb to the gates of the city. The suburbs of Saint-Sernin and Saint-Pierre des Cuisines also had a remarkable expansion.

12th century

The end of the 11th century marked the departure of count Raymond IV to the crusades. Various succession wars followed, besieging Toulouse several times. In 1119, the population of Toulouse proclaimed Alphonse Jourdain count. Alphonse Jourdain, willing to be grateful to his people, reduced the taxes immediately.

With the death of the count, an administration of 8 "capitulaires" was created. Under the direction of the count, they had the responsibility of regulating the exchanges and making sure the laws were applied. These were the Capitouls, whose first acts were dated in 1152.

In 1176, the "chapitre" already had 12 members, each of them representing a district of Toulouse, or a suburb. The consuls quickly opposed count Raimond V. The population of Toulouse was divided on the subject, and after 10 years of fighting, in 1189, the town council finally obtained the submission of the count.

In 1190 began the construction of the future Capitole, the common house, the town council headquarters. With 24 members, probably elected, the Capitouls granted themselves the rights of police, trade, imposition and started some conflicts with the closest cities. Toulouse was usually victorious, extending the domination of the patria tolosana.

Despite the intervention of the King, the administration of the Capitouls gave a relative independence to the city, for nearly 600 years, until the French Revolution.

Anecdotally, the players of the Stade Toulousain, the local Rugby team, today wear the red and black colors of the Capitouls.

13th century

Catharism is a doctrine professing the separation of the material and the spiritual existences, one of its possible inspiration may be Bogomilism of Bulgaria. It conflicts with the orthodox confession. Called "heretics", the Cathars found a strong audience in the south of France, and during the 12th century. Simon de Montfort tried to exterminate them.

Toulouse was reached by the Cathar doctrine too. The orthodox White Brotherhood pursued the hereticals Blacks in the streets of the city. The abbot of Foulques took advantage of this because the heretics were his creditors, and encouraged this inquisition.

Some people joined the white fighters, others chose to assist the besieged population. The consuls did not wish to encourage the division of Toulouse, and defied the pontifical authority, refusing to identify the heretics. Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, a Catholic, who was excommunicated for his dispute with the pope, later sympathised with the heretics because he saw the crusade take an unholy path with the extermination at Bézier.

In 1211, the first siege of Toulouse by Simon de Montfort was unsuccessful but two years later, he successfully defeated the Toulouse army. Under the threat of killing many hostages, he entered the city in 1216, and appointed himself as a count.

Simon de Montfort was killed by a stone at the Siege of Toulouse in 1218. Until the last siege, the "whites" were fought against by the Toulouse populace. Louis VII finally decided to give up in 1219. Raymond VI recognized the support he had received from the population, helping him to preserve his interests, gave up his last prerogatives to the Capitouls.

13th to 14th century

The 13th century went in a political direction opposite to the path drawn by the past centuries. In 1229, the Treaty of Paris introduced the University of Toulouse, intending to teach theology as well as Aristotelian philosophy. Copied from the Parisian model, the teaching was supposed to dissolve the heretic movement.

Various monastic orders, like the congregation of the order of frères prêcheurs (Dominican Order), were started. They found home in Les Jacobins. In parallel, a long period of inquisition began inside the Toulouse walls. The fear of repression obliged the notabilities to exile, or to convert themselves. The inquisition lasted nearly 400 years, making Toulouse its capital.

Count Raimond VII was convicted of heresy and died in 1249 without an heir. The Toulouse county was given to the King of France, who imposed his laws. The power of the Capitouls was reduced.

In 1323 the Consistori del Gay Saber was established in Toulouse to preserve the lyric art of the troubadours. Toulouse became the centre of Occitan literary culture for the next hundred years; the Consistori was last active in 1484.

Reinforcing its place as an administrative center, the city grew richer, participating in the trade of Bordeaux wine with England, as well as cereals and textiles.

Accompanying the inquisition, many threats affected the city. Plague, fire and flood devastated the districts. The Hundred Years' War decimated Toulouse. Despite strong immigration, the population lost 10,000 inhabitants in 70 years. Toulouse only had 22,000 people in 1405.

15th to 16th century

The 15th century began with the creation of the Parlement by Charles VII. Promising an exemption of taxes, the King reinforced his influence and defied the administration of the Capitouls. Invested with the rights of jurisdiction, the Parlement gained its political independence thereafter.

This century is also the stage of many food shortages. The roads were worn and unreliable, and Toulouse experienced a terrible fire in 1463. The dwellings located between the current rue Alsace-Lorraine and the Garonne river were decimated. The city encountered a new demographic expansion, resulting in a true housing shortage.

Continuing the textile activity of the city, the trade of fabric dye woad increased from 1463. This dye was called at the time pastel and triggered the most prosperous period of the Toulouse history. Toulouse used its newfound wealth to build the magnificent homes and public buildings that are today the core of the old city. A rich representative of this era was Pierre D'Assézat.

The prosperity did not last. Woad was to be eclipsed by indigo from the New World, which produced a darker and more colorfast blue.

In the middle of the 16th century, the University of Toulouse comprised nearly 10,000 students. A humanistic tide crossed its walls and the academics were often agitated. The inquisition continued to burn people at the stake.

During the 1562 Riots of Toulouse street battles between Huguenots and Catholics resulted in over 3000 deaths and the purposeful burning of 200 homes in the Saint-Georges quarter.

D'Assézat was expelled, after which 32 years of civil war began.

17th century

With Henry IV acceding to the throne, the Toulouse disorders came to an end. The Parlement recognized the King of France and the edict of Nantes was accepted in 1600. The Capitouls lost the last influence they had. A threat much more serious than La Fronde reached Toulouse in 1629 and 1652, leaving thousands of victims: the plague.

For the first time, the municipality and the local Parlement took measures together to assist the people affected by the epidemic. Most of the clergy left the city. The richest people also fled. Only the doctors were required to stay. Starvation led the remaining Capitouls to prevent the butchers and the bakers from leaving.

The La Grave hospital welcomed the people hit by the epidemic, and placed them in quarantine. The Pré des Sept Deniers also welcomed many patients under precarious conditions. Before closing its gates, the city became a den of beggars attracted by a medical infrastructure which held more hope than the countryside. The money failed to feed the population, and some requisitions were ordered. At the worst moments of the crisis, the rich were responsible for the poor.

In 1654, when the second epidemic ended, the city was devastated. However, during the periods of no plague two major projects were completed: the Pont-Neuf in 1632 and the Canal du Midi in 1682. This troubled century ended with a last starvation, in 1693.

The seventeenth century marked the arrival of a secret association, Aa (associatio amicorum), bringing together members of the clergy and academics, and preaching an exacerbated faith. The influence of this organization became particularly strong during the eighteenth century.

18th century

Various artistic, religious, and architectural currents traversed the city during the 18th century.

Louis de Mondran was the instigator of a new town planning, probably inspired by his stay in the capital. The principal achievements of this period were the Grand Rond, the Cours Dillon, and the frontage of the Capitole.

In 1770, the Cardinal of Brienne inaugurated the first stone of the channel that was named after him. The channel that connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, and the Canal du Midi to the Canal Lateral à la Garonne were finished six years later. The point of junction is known under the name of Ponts-Jumeaux.

The city grew more pecuniary, impoverishing the most stripped, and enriching the nobility and the clergy. The local architects and the sculptors became very busy, thanks to the numerous fortunate individuals. The Reynerie was the summer residence of the husband of the Comtesse du Barry.

Toulouse did not forget its traditional religious enthusiasm, even if the end of the 18th century marks a certain decline. New congregations began to appear—most famously the Blue Penitents—officiating as the Saint-Jérome church. The local Parlement, infiltrated by the Aa group (see 17th century), regulated the religious life, and condemned the Protestants.

The Calas affair began in this difficult context. With Parlement deciding the execution of Jean Calas, they demonstrated their newly acquired control of the city.

Worried for its autonomy, the Toulouse population supported the Parlement when threatened by the monarchy. The Capitouls were now chosen by the Parlement, and only 8 representatives were allowed. A revolution would become necessary for the town to escape from the Parlement lead.

19th century

The French Revolution is a major event in the Toulouse history. It changed the role of the city, as well as its political and social structure.

The city was one of many spectators of the Parisian movement. The on-coming of the protests of July 14, 1789 had minor repercussions, punctuated by some plundering. Five months later, when the Ancien Régime was abolished, a new order took over. The members of the Parlement and the Capitouls fought to preserve their privileges, they demonstrated on September 25, and hardly received any support from a population which did not recognize its former protectors.

The regional influence of Toulouse, formerly ensured by its Parlement, was reduced to a department, Haute-Garonne. The clergy was required to yield to the "Civil Constitution of the Clergy" imposed by the constituent assembly. A new archbishop was named despite the disagreement of Loménie de Brienne. Part of the population was hostile to these reforms and their financial impact.

The prerogatives of the Capitouls were abolished on December 14, 1789. Joseph de Rigaud was the first mayor, elected on February 28, 1790.

In 1793, during the Commune, Toulouse refused to join the Provence and Aquitaine federalists in going to Paris. The prospects of the war against Austria and those of the interior resistance's initiated the Terror, purifying Toulouse from part of the refractors to the Revolution.

In 1799, the fortified city resisted the attack of the British and Spanish royalist armies, during the first battle of Toulouse. The elevation of Napoleon to the head of the new regime, then empire, restored partially the regional statute of the city. The emperor even came to Toulouse in 1808, and gave in particular the Daurade cloister to the tobacco factory.

In 1814, during the battle of Toulouse, the British army entered the city abandoned by the imperial army. Hence 10 April 1814 marks the last battle of the Empire: Napoleon having abdicated eight days earlier (but unfortunately the French commander, Soult, hadn't yet been informed!) The army of Wellington was welcomed there by a great number of royalists, which prepared Toulouse for the Restoration of Louis XVIII.

Modern day

Toulouse suffered the explosion of the AZF chemical plant, owned by the Société nationale des poudres et des explosifs, on September 21, 2001. The plant was totally destroyed and the explosion damaged many houses, schools, churches, monuments and shops. More than 20,000 flats were damaged. The plant is 8 km (5.0 mi) from the centre of Toulouse. Twenty nine people died and several thousand were injured. The root of the explosion was in a building containing ammonium nitrate.[1]

In March 2012, a local Islamic extremist, Mohammed Merah, opened fire at a Jewish school in Toulouse, killing a teacher and three children. One of the slain children, an eight-year-old girl, was shot in the head at point-blank range. A 17-year-old boy was also critically wounded in the shooting. President Nicolas Sarkozy said that it was "obvious" it was an anti-Semitic attack[2] and that, "I want to say to all the leaders of the Jewish community, how close we feel to them. All of France is by their side." The Israeli Prime Minister condemned the "despicable anti-Semitic" murders.[3][4] After a 32-hour siege and standoff with the police outside his house, and a French raid, Merah jumped off a balcony and was shot in the head and killed.[5] Merah had told police during the standoff that he intended to keep on attacking, and he loved death the way the police loved life. He also claimed connections with al-Qaeda.[6][7][8]

See also

- Counts of Toulouse

- Timeline of Toulouse

References

- ↑ Henley, Jon (2001-10-04). "Terrorism link to French explosion". The Guardian (London: GMG). ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ "School Shooting Gun Same As Other Attacks". Sky News. March 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Netanyahu: Murder in French Jewish school a 'despicable anti-Semitic' attack". Haaretz. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Toulouse shooting: Same gun and motorbike used in Jewish and soldier attacks". Daily Telegraph. 19 Mar 2012.

- ↑ Tracy McNicoll (2012-03-22). "Mohamed Merah Dies in French Standoff’s Gory End". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ↑ "Toulouse terrorist was going to keep kil...". The Jerusalem Post. 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ↑ "Toulouse killer: I'm not afraid of death". Ynetnews.com. 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ↑ AFP (2012-07-09). "France probes gunman siege tapes". The Australian. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th-20th century

- "Toulouse", A Handbook for Travellers in France, London: John Murray, 1861

- "Toulouse", The Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910, OCLC 14782424

- "Toulouse", Southern France, including Corsica (6th ed.), Leipzig: Baedeker, 1914

- Published in the 21st century

- Anne Le stang, Histoire de Toulouse illustrée, Toulouse, Le Pérégrinateur Éditeur, 2006, ISBN 2-910352-44-7, in French

- Helen ISAACS and Jeremy KERRISON, The Practical guide to Toulouse, 6th edition, Toulouse, 2008 Le Pérégrinateur Éditeur, ISBN 2-910352-46-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Toulouse. |