History of Spain (1814–73)

| Kingdom of Spain | ||||||

| Reino de España | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Motto Plus Ultra "Further Beyond" | ||||||

| Anthem Marcha Real "Royal March" (1813–1822; 1823–1873) Himno de Riego "Anthem of Riego" (1822–1823) | ||||||

The Kingdom of Spain in 1850. | ||||||

| Capital | Madrid | |||||

| Languages | Spanish | |||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | |||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1813–1820; 1823–1833) Constitutional monarchy (1820–1823; 1833–1871) Parliamentary monarchy (1871–1873) | |||||

| King | ||||||

| - | 1813–1833 | Ferdinand VII | ||||

| - | 1833–1868 | Isabella II | ||||

| - | 1870–1873 | Amadeo I | ||||

| Regent | ||||||

| - | 1813–1814 | Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga | ||||

| - | 1869–1871 | Francisco Serrano | ||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||

| - | 1813–1814 | José Luyandoa | ||||

| - | 1872–1873 | Manuel Ruiz Zorrillab | ||||

| Legislature | Cortes Generales | |||||

| - | Upper house | Senate | ||||

| - | Lower house | Congress of Deputies | ||||

| Historical era | 19th century | |||||

| - | Treaty of Valençay | 11 December 1813 | ||||

| - | Amadeo I abdicates | 11 February 1873 | ||||

| Currency | Spanish escudo (1813–1869) Spanish peseta (1869–1873) | |||||

| a. | as First Secretary of State | |||||

| b. | as President of the Council of Ministers | |||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Spain |

.svg.png) |

|

|

| Timeline |

| Spain portal |

Spain in the 19th century was a country in turmoil. Occupied by Napoleon from 1808 to 1814, a massively destructive "war of independence" ensued, driven by an emergent Spanish nationalism. An era of reaction against the liberal ideas associated with revolutionary France followed the war, personified by the rule of Ferdinand VII and – to a lesser extent – his daughter Isabella II. Ferdinand's rule included the loss of the Spanish colonies in the New World, except for Cuba and Puerto Rico, in the 1810s and 1820s. A series of civil wars then broke out in Spain, pitting Spanish liberals and then republicans against conservatives, culminating in the Carlist Wars between the moderate Queen Isabella and her uncle, the reactionary Infante Carlos. Disaffection with Isabella's government from many quarters led to repeated military intervention in political affairs and to several revolutionary attempts against the government. Two of these revolutions were successful, the moderate Vicalvarada or "Vicálvaro Revolution" of 1854 and the more radical la Gloriosa (Glorious Revolution) in 1868. The latter marks the end of Isabella's monarchy. The brief rule of the liberal king Amadeo I of Spain ended in the establishment of the First Spanish Republic, only to be replaced in 1874 by the popular, moderate rule of Alfonso XII of Spain, which finally brought Spain into a period of stability and reform.

Reaction (1814–1820)

_by_Goya.jpg)

King Ferdinand VII's refusal to agree to the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812 on his accession to the throne in 1814 came as little surprise to most Spaniards; the king had signed on to agreements with the clergy, the church, and with the nobility in his country to return to the earlier state of affairs even before the fall of Napoleon. The decision to abrogate the Constitution was not welcomed by all, however. Liberals in Spain felt betrayed by the king who they had decided to support, and many of the local juntas that had pronounced against the rule of Joseph Bonaparte lost confidence in the king's rule. The army, which had backed the pronouncements, had liberal leanings that made the king's position tenuous. Even so, agreements made at the Congress of Vienna (where Spain was represented by Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador) starting a year later would cement international support for the old, absolutist regime in Spain.

The Spanish Empire in the New World had largely supported the cause of Ferdinand VII over the Bonapartist pretender to the throne in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars. Joseph had promised radical reform, particularly the centralization of the state, which would cost the local authorities in the American empire their autonomy from Madrid. The Spanish Americans, however, did not support absolutism and wanted auto-governance. The juntas in the Americas did not accept the governments of the Europeans, neither the French or Spaniards.

Already in 1810, the Caracas and Buenos Aires juntas declared their independence from the Bonapartist government in Spain and sent ambassadors to the United Kingdom. The British blockade against Spain had also moved most of the Latin American colonies out of the Spanish economic sphere and into the British sphere, with whom extensive trade relations were developed. When Ferdinand's rule was restored, these juntas were cautious of abandoning their autonomy, and an alliance between local elites, merchant interests, nationalists, and liberals opposed to the abrogation of the Constitution of 1812 rose up against the Spanish in the New World.

Although Ferdinand was committed to the reconquest of the colonies, along with many of the Continental European powers, Britain was ostensibly opposed to the move which would limit her new commercial interests. Latin American resistance to Spanish reconquest of the colonies was compounded by uncertainty in Spain itself, over whether or not the colonies should be reconquered; Spanish liberals – including the majority of military officers – already disdainful of the monarchy's rejection of the constitution, were opposed to the restoration of an empire that they saw as an obsolete antique, as against the liberal revolutions in the New World with which they sympathized.

The arrival of Spanish forces in the American colonies began in 1814, and was briefly successful in restoring central control over large parts of the Empire. Simón Bolívar, the leader of revolutionary forces in New Granada, was briefly forced into exile in British-controlled Jamaica, and independent Haiti. In 1816, however, Bolívar found enough popular support that he was able to return to South America, and in a daring march from Venezuela to New Granada (Colombia), he defeated Spanish forces at the Battle of Boyacá in 1819, ending Spanish rule in Colombia. Venezuela was liberated June 24, 1821 when Bolívar destroyed the Spanish army on the fields of Carabobo on the Battle of Carabobo. Argentina declared its independence in 1816 (though it had been operating with virtual independence as a British client since 1810 after successfully resisting a British invasion). Chile was retaken by Spain in 1814, but lost permanently in 1817 when an army under José de San Martín, crossed the Andes Mountains from Argentina to Chile, and went on to defeat Spanish royalist forces at the Battle of Chacabuco in 1817.

Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and Central America still remained under Spanish control in 1820. King Ferdinand, however, was dissatisfied with the loss of so much of the Empire and resolved to retake it; a large expedition was assembled in Cadiz with the aim of reconquest. However the army was to create political problems of its own.

Liberal Triennium (1820–1823)

A conspiracy of liberal mid-ranking officers in the expedition being outfitted at Cadiz mutinied before they were shipped to the Americas. Led by Rafael del Riego, the conspirators seized their commander and led their army around Andalusia hoping to gather support; garrisons across Spain declared their support for the would-be revolutionaries. Riego and his co-conspirators demanded that the liberal Constitution of 1812 be restored. Before the coup became an outright revolution, King Ferdinand agreed to the demands of the revolutionaries and swore by the constitution. A "Progresista" (liberal) government was appointed, though the king expressed his disaffection with the new administration and constitution.

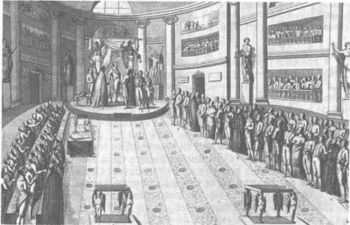

Three years of liberal rule (the Trienio Liberal) followed. The Progresista government reorganized Spain into 52 provinces, and intended to reduce the regional autonomy that had been a hallmark of Spanish bureaucracy since Habsburg rule in the 16th and 17th centuries. The opposition of the affected regions – in particular, Aragon, Navarre, and Catalonia – shared in the king's antipathy for the liberal government. The anticlerical policies of the Progresista government led to friction with the Roman Catholic Church, and the attempts to bring about industrialization alienated old trade guilds. The Inquisition—which had been abolished by both Joseph Bonaparte and the Cádiz Cortes during the French occupation—was ended again by the Progresista government, summoning up accusations of being nothing more than afrancesados (Francophiles), who only six years before had been forced out of the country. More radical liberals attempted to revolt against the entire idea of a monarchy, constitutional or otherwise, in 1821; these republicans were suppressed, though the incident served to illustrate the frail coalition that bound the Progresista government together.

The election of a radical liberal government in 1823 further destabilized Spain. The army – whose liberal leanings had brought the government to power – began to waver when the Spanish economy failed to improve, and in 1823, a mutiny in Madrid had to be suppressed. The Jesuits (who had been banned by Charles III in the 18th century, only to be rehabilitated by Ferdinand VII after his restoration) were banned again by the radical government. For the duration of liberal rule, King Ferdinand (though technically head of state) lived under virtual house arrest in Madrid.

The Congress of Vienna ending the Napoleonic Wars had inaugurated the "Congress system" as an instrument of international stability in Europe. Rebuffed by the "Holy Alliance" of Russia, Austria, and Prussia in his request for help against the liberal revolutionaries in 1820, by 1822 the "Concert of Europe" was at sufficient unease with Spain's liberal government and its surprising hardiness that they were prepared to intervene on Ferdinand's behalf. In 1822, the Congress of Verona authorized France to intervene. Louis XVIII of France – himself an arch-reactionary – was only too happy to put an end to Spain's liberal experiment, and a massive army – the "100,000 Sons of Saint Louis" – was dispatched across the Pyrenees in April 1823. The Spanish army, fraught by internal divisions, offered little resistance to the well organised French force, who seized Madrid and reinstalled Ferdinand as absolute monarch. The liberals' hopes for a new Spanish War of Independence were not to be fulfilled.

Although Mexico had been in revolt in 1811 under Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, resistance to Spanish rule had largely been confined to small guerrilla bands in the countryside. The coup in Spain did not change the centralized policies of the government of Trieno Liberal in Madrid and many Mexicans were disappointed. In 1821, Mexico led by Agustin de Iturbide and Vincente Guerrero presented the Plan de Iguala, calling for an independent Mexican monarchy, in response to the centralism and fears of the liberalism and anticlericalism in Spain. The liberal government of Spain showed less interest in the military reconquest of the colonies than Ferdinand, although it rejected the independence of Mexico in the failed Treaty of Córdoba. The last bastion of San Juan de Ulúa resisted to 1825, and Isidro Barradas tried to recapture Mexico from Cuba in 1829.

José de San Martín, who had already helped to liberate Chile and Argentina, entered Peru in 1820. In 1821, the inhabitants of Lima invited him and his soldiers to the city. The viceroy fled into the interior of the country. From there he resisted successfully, and it was only with the arrival of Simón Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre in 1823 that the Spanish royalist forces were defeated at the battles of Junin and Ayacucho, where the entire Spanish Army of Peru and the Viceroy were captured. The Battle of Ayacucho signified the end of the Spanish Empire on the American mainland.

The Ominous Decade (1823–1833)

.jpg)

Immediately following the restoration of absolutist rule in Spain, King Ferdinand embarked on a policy intended to restore old conservative values to government; the Jesuit Order and the Spanish Inquisition were reinstated once more, and some autonomy was again devolved to the provinces of Aragon, Navarre, and Catalonia. Although he refused to accept the loss of the American colonies, Ferdinand was prevented from taking any further action against the rebels in the Americas by the opposition of the United Kingdom and the United States, who voiced their support of the new Latin American republics in the form of the Monroe Doctrine. The recent betrayal of the army demonstrated to the king that his own government and soldiers were untrustworthy, and the need for domestic stability proved to be more important than the reconquest of the Empire abroad. As a result, the destinies of Spain and her empire on the American mainland were to permanently take separate paths.

Although in the interests of stability Ferdinand issued a general amnesty to all those involved in the 1820 coup and the liberal government that followed it, the original architect of the coup, Rafael del Riego, was executed. The liberal Partido Progresista, however, continued to exist as a political force, even if it was excluded from actual policy-making by Ferdinand's restored government. Riego himself was hanged, and he would become a martyr for the liberal cause in Spain and would be memorialized in the anthem of the Second Spanish Republic, El Himno de Riego, more than a century later.

The remainder of Ferdinand's reign was spent restoring domestic stability and the integrity of Spain's finances, which had been in ruins since the occupation of the Napoleonic Wars. The end of the wars in the Americas improved the government's financial situation, and by the end of Ferdinand's rule the economic and fiscal situation in Spain was improving. A revolt in Catalonia was crushed in 1827, but at large the period saw an uneasy peace in Spain.

Ferdinand's chief concern after 1823 was how to solve the problem of his own succession. He was married four times in his life, and bore two daughters in all his marriages; the succession law of Philip V of Spain, which still stood in Ferdinand's time, excluded women from the succession. By that law, Ferdinand's successor would be his brother, Carlos. Carlos, however, was a reactionary and an authoritarian who desired the restoration of the traditional moralism of the Spanish state, the elimination of any traces of constitutionalism, and a close relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. Though surely not a liberal, Ferdinand was fearful of Carlos's extremism. War had broken out in neighboring Portugal in 1828 as a result of just such a conflict between reactionary and moderate forces in the royal family – the War of the Two Brothers.

In 1830, at the advice of his wife, Maria Christina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Ferdinand decreed a Pragmatic Sanction that had the effect of fundamental law in Spain. As a result of the sanction, women were allowed to accede to the Spanish throne, and the succession would fall on Ferdinand's infant daughter, Isabella, rather than to his brother Carlos. Carlos – who disputed the legality of Ferdinand's ability to change the fundamental law of succession in Spain – left the country for Portugal, where he became a guest of Dom Miguel, the absolutist pretender in that country's civil war.

Ferdinand died in 1833, at the age of 49. He was succeeded by his daughter Isabella under the terms of the Pragmatic Sanction, and his wife, Maria Christina, became regent for her daughter, who at that time was only three years of age. Carlos disputed the legitimacy of Maria Christina's regency and the accession of her daughter, and declared himself to be the rightful heir to the Spanish throne. A half-century of civil war and unrest would follow.

The Carlist War and the Regencies (1833–1843)

After their fall from grace in 1823 at the hands of a French invasion, Spanish liberals had pinned their hopes on Ferdinand VII's wife, Maria Cristina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, who bore some marks as a liberal and a reformer. However, when she became regent for her daughter Isabella in 1833, she made it clear to the court that she intended no such reforms. Even still, an alliance of convenience was formed with the progresista faction at court against the conservatives, who backed the rebel Infante Carlos of Spain.

Carlos, who declared his support for the ancient, pre-Bourbon privileges of the fueros, received considerable support from the Basque country, Aragon, and Catalonia, which valued their ancient privileges from Madrid. The insurrection seemed, at first, a catastrophic failure for the Carlists, who were quickly driven out of most of Aragon and Catalonia, and forced to cling to the uplands of Navarre by the end of 1833. At this crucial moment, however, Carlos named the Basque Tomás de Zumalacárregui, a veteran guerrilla of the Peninsular War, to be his commander-in-chief. Within a matter of months, Zumalacárregui reversed the fortunes of the Carlist cause and drove government forces out of most of Navarre, and launched a campaign into Aragon. By 1835, what was once a band of defeated guerrillas in Navarre had turned into an army of 30,000 in control of all of Spain north of the Ebro River, with the exception of the fortified ports on the northern coast.

.jpg)

The position of the government was growing increasingly desperate. Rumors of a liberal coup to oust Maria Cristina abounded in Madrid, compounding the danger of the Carlist army which was now within striking distance of the capital. Appeals for aid did not fall on deaf ears; France, which had replaced the reactionary monarchy of Charles X with the liberal monarchy of Louis-Philippe in 1830, was sympathetic to the Cristino cause. The Whig governments of Viscount Melbourne were similarly friendly, and organized volunteers and material aid for Spain. Still confident of his successes, however, Don Carlos joined his troops on the battlefield. While Zumalacárregui agitated for a campaign to take Madrid, Carlos ordered his commander to take a port on the coast. In the subsequent campaign, Zumalacárregui died after being shot in the calf. There was suspicion that Carlos, jealous of his general's successes and politics, conspired to have him killed.

Having failed to take Madrid, and having lost their popular general, the Carlist armies began to weaken. Reinforced with British equipment and manpower, Isabella found in the progressista general Baldomero Espartero a man capable of suppressing the rebellion; in 1836, he won a key victory at the Battle of Luchana that turned the tide of the war. After years of vacillation on the issue of reform, events compelled Maria Cristina to accept a new constitution in 1837 that substantively increased the powers of the Spanish parliament, the cortes. The constitution also established state responsibility for the upkeep of the church, and a resurgence of anti-clerical sentiment, led to the disbandment of some religious orders which considerably reduced the strength of the Church in Spain. The Jesuits – expelled during the Trienio Liberal and readmitted by Ferdinand – were once again expelled by the wartime regency in 1835.

The Spanish government was growing deeper in debt as the Carlist war dragged on, nearly to the point that it became insolvent. In 1836, the president of the government, Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, offered a program of desamortización, the Ecclesiastical Confiscations of Mendizábal, that involved the confiscation and sale of church, mainly monastic, property. Many liberals, who bore anti-clerical sentiments, saw the clergy as having allied with the Carlists, and thus the desamortización was only justice. Mendizábal recognized, also, that immense amounts of Spanish land (much of it given as far back as the reigns of Philip II and Philip IV) were in the hands of the church lying unused – the church was Spain's single largest landholder in Mendizábal's time. The Mendizábal government also passed a law guaranteeing freedom of the press.

After Luchana, Espartero's government forces successfully drove the Carlists back northward. Knowing that much of the support for the Carlist cause came from supporters of regional autonomy, Espartero convinced the Queen-Regent to compromise with the fueros on the issue of regional autonomy and retain their loyalty. The subsequent Convention of Vergara in 1839 was a success, protecting the privileges of the fueros and recognizing the defeat of the Carlists. Don Carlos once again went into exile.

Freed from the Carlist threat, Maria Cristina immediately embarked on a campaign to undo the Constitution of 1837, provoking even greater ire from the liberal quarters of her government. Failing in the attempt to overthrow her own constitution, she attempted to undermine the rule of the municipalities in 1840; this proved to be her undoing. She was forced to name the progressista hero of the Carlist War, General Espartero, president of the government. Maria Cristina resigned the regency after Espartero attempted a program of reform.

In the absence of a regent, the cortes named Espartero to that post in May 1841. Although a noted commander, Espartero was inexperienced with politics and his regency was markedly authoritarian; it was arguably Spain's first experience with military rule. The government wrangled with Espartero over the choice of Agustín Argüelles, a radical liberal politician, as the young queen's tutor. From Paris, Maria Cristina railed against the decision and attracted the support of the moderados in the Cortes. The war heroes Manuel de la Concha and Diego de León attempted a coup in September 1841, attempting to seize the queen, only months after Espartero was named regent. The severity with which Espartero crushed the rebellion led to considerable unpopularity; the Cortes, increasingly rebellious against him, selected an old rival, José Ramón Rodil y Campillo, as their chief minister. Another uprising in Barcelona in 1842 against his free trade policies prompted him to bombard the city, serving only to loosen his tenuous grip on power. On 20 May 1843, Salustiano Olózaga delivered his famous "Dios salve al país, Dios salve a la reina!" (God save the country, God save the queen!) speech that led to a strong moderate-liberal coalition that opposed Espartero. This coalition sponsored a third and final uprising led by generals Ramón Narváez and Francisco Serrano, who finally overthrew Espartero in 1843, after which the deposed regent fled to England.

Moderado rule (1843–1849)

The cortes, now exasperated by serial revolutions, coups, and counter-coups, decided not to name another regent, and instead declared that the 13 year-old Isabella II was of age. Isabella, now inundated with the competing interests of courtiers espousing an array of ideologies and interests, vacillated as her mother did between them, and served to aggravate those genuinely interested in progress and reform. Salustiano Olózaga was named the first president of the government after Espartero's fall. His commission to form a government was, however, highly unpopular with the cortes; he allegedly received the authority to dissolve the cortes from the queen, but the queen within days withdrew her support for the plan, and cast her lot behind Olózaga's opponent in the cortes, the Minister of State Luis González Bravo. Olózaga was accused of obtaining the order of dissolution by forcing Queen Isabella to sign against her will. Olózaga had to resign, having only been President of the Government for an ephemeral fifteen days. Olózaga, a liberal, was succeeded by Luis González Bravo, a moderate, inaugurating a decade of moderado rule. President Luis González Bravo was Isabella's first stable president during her effective kingdom, ruling for 6 straight months (from that moment on he would remain loyal to the queen until the end of her kingdom, acting as her very last president decades later at the outbreak of the 1868 Revolution). Isabella's kingdom was to include unstable administration, policies, and governments, due to the various opposition parties that continuously wanted to take over her government – in 1847, for instance, she went through five Presidents of the Government.

Luis González Bravo, leading the moderate faction, dissolved the cortes himself and ruled by royal decree. He declared Spain to be in a state of siege and dismantled a number of institutions that had been set up by the progressista movement such as elected city councils. Fearing another Carlist insurrection in northern Spain, he established the Guardia Civil, a force merging police and military functions to retain order in the mountainous regions that had been the Carlists' base of support and strength, so as to defend Isabella's rightful kingdom from her enemies.

A new constitution, authored by the moderados was written in 1845. It was backed by the new Narváez government begun in May 1844, led by General Ramón Narváez, one of the original architects of the revolution against Espartero. A series of reforms promulgated by Narváez's government attempted to stabilize the situation. The cortes, which had been uneasy with the settlement with the fueros at the end of the First Carlist War, were anxious to centralize the administration. The law of 8 January 1845 did just that, stifling local autonomy in favor of Madrid; the act contributed to the revolt of 1847 and the revival of Carlism in the provinces. The Electoral Law of 1846 limited the suffrage to the wealthy and established a property bar for voting. In spite of Bravo and Narváez's efforts to suppress the unrest in Spain, which included lingering Carlist sentiments and progressista supporters of the old Espartero government, Spain's situation remained uneasy. A revolt led by Martín Zurbano in 1845 included the support of key generals, including Juan Prim, who was imprisoned by Narváez.

Narváez ended the sale of church lands promoted by the progresistas. This put him into a difficult situation, as the progresistas had had some progress in improving Spain's financial situation through those programs. The Carlist War, the excesses of Maria Cristina's regency, and the difficulties of the Espartero government left the finances in a terrible situation. Narváez entrusted the finances to the minister Alejandro Mon, who embarked on an aggressive program to restore solvency to Spain's finances; in this he was remarkably successful, reforming the tax system which had been badly neglected since the reign of Charles IV. With its finances more in order, the government was able to rebuild the military and, in the 1850s and 1860s, embark on successful infrastructure improvements and campaigns in Africa that are often cited as the most productive aspects of Isabella's reign.

Isabella was convinced by the Cortes to marry her cousin, a Bourbon prince, Francis, Duke of Cádiz. Her younger sister Maria Louisa Fernanda was married to the French king Louis-Philippe's son Antoine, Duke of Montpensier. The Affair of the Spanish Marriages threatened to break the alliance between Britain and France, which had come to a different agreement over the marriage. France and Britain nearly went to war over the issue before it was resolved; the affair contributed to the fall of Louis-Philippe in 1848. Fury raged in Spain over the queen's nonchalance with the national interest and worsened her public image.

Partly as a result of this, a major rebellion broke out in northern Catalonia in 1846, the Second Carlist War. Rebels led by Rafael Tristany launched a guerilla campaign against government forces in the region and pronounced themselves in favor of Carlos, Conde de Montemolin, carrier of the Carlist cause and son of Infante Carlos of Spain. The rebellion grew, and by 1848 it was relevant enough that Carlos sponsored it himself and named Ramón Cabrera as commander of the Carlist armies in Spain. A force of 10,000 men was raised by the Carlists; in response to fears of further scalation Narváez was once again named President of the Government in Madrid in October 1847. The biggest battle of the war, the Battle of Pasteral (January 1849) was inconclusive; Cabrera, however, was wounded and lost confidence. His departure from Spain caused the rebellion dissolve by May 1849. The Second Carlist War, though contemporaneous with the revolutions of 1848, is rarely included as part of the same phenomenon, since the rebels in Spain were not fighting for liberal or socialist ideas, but rather conservative and even absolutist ones.

Rule by pronunciamento (1849–1856)

Ramón Narváez was succeeded by Juan Bravo Murillo, a practical man and a seasoned politician. Murillo carried the same authoritarian tendencies as Narváez but made serious efforts to advance Spanish industry and commerce. He surrounded himself with technocrats who attempted to take an active role in the advancement of the Spanish economy. An aggressive policy of financial reform was coupled with an equally aggressive policy of infrastructure improvement enabled by Alejandro Mon's financial reforms in the preceding decade. A serious effort to build a rail network in Spain was begun by the Murillo government.

Murillo, facing the issue of anti-clericalism, signed a concordat with the Vatican on the issue of religion in Spain; it was conclusively decided that Roman Catholicism remained the state religion of Spain, but that the contribution of the church in education would be regulated by the state. In addition, the state renounced desamortización, the process of selling church lands. Murillo's negotiations with the Papacy were aided by Narváez's role in the Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states, where he had led Spanish soldiers in the pope's defense against revolutionaries.

Murillo, flush with economic and international successes, announced a series of policies on 2 December 1852 to the cortes. Prominent among the reforms he suggested were the reduction of the powers of the cortes as a whole in favor of Murillo's office as president of the government, and the ability for the executive to legislate by decree in times of crisis. Twelve days later, the cortes successfully convinced the queen to sack Murillo and find a new minister.

The next president of the government, Federico Roncali, governed briefly, and did well to maintain a civil atmosphere with the cortes after Murillo's flamboyance. The army, dissatisfied with Roncali a few months later, convinced the queen to oust him, replacing him with General Francisco Lersundi. The cortes, which by then were unsatisfied with the army's intervening in government affairs, arranged for Luis José Sartorius, the Count of San Luis, to be named president of the government. Sartorius – who had gained power only by betraying Luis González Bravo and following the fortunes of General Narváez – was notorious for falsifying election results in favor of his co-conspirators and himself. His appointment as President of the Government drew violent agitation from the liberal wing of the Spanish government.

In July 1854, a major rebellion broke out bringing together a wide coalition of outrages against the state. The Crimean War, which had broken out in March of that year, had led to an increase in grain prices across Europe and a famine in Galicia. Riots against the power loom erupted in the cities, and progresistas outraged at a decade of moderado dictatorship and the corruption of the Sartorius government broke out in revolution. General Leopoldo O'Donnell took the lead in the revolution; after the indecisive Battle of Vicálvaro, he issued the Manifesto of Manzanares that pronounced himself in favor of Spain's former progresista dictator, Baldomero Espartero, the man that O'Donnell had actively rebelled against in 1841. The moderado government collapsed before them and Espartero returned to politics at the head of an army.

Espartero was named president of the government once again, this time by the very queen for whom he had been regent ten years before. Espartero, indebted to O'Donnell for restoring him to power but concerned about having to share power with another man, tried to get him installed to a post as far away from Madrid as possible – in this case, in Cuba. The attempt failed and only alienated Espartero's colleague; instead, O'Donnell was given a seat in Espartero's cabinet as war minister, though his influence was greater than his portfolio.

The two caudillos, who came into power with immense popularity, attempted to reconcile their differences and form a coalition party that crossed the progresista-moderado lines that had dominated and restricted Spanish politics since the Peninsular War. The "Unión Liberal", as it was called, attempted to forge a policy based on progress in industry, infrastructure, public works, and a national compromise on constitutional and social issues.

Espartero attempted to rebuild the progresista government after ten years of moderado reform. Most of Espartero's tenure was absorbed into promulgating the new constitution he intended to replace the moderado constitution of 1845. The resistance of the cortes, however, meant that most of his term was spent deadlocked; the coalition that Espartero relied on was built on both liberals and moderates, who disagreed fundamentally on the ideology of the new constitution and policies. Espartero's constitution included provisions for the freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and, most importantly, a more liberal suffrage than the Constitution of 1845 allowed for. Even before the constitution had been passed, Espartero endorsed Pascual Madoz's desamortización against communal lands in Spain; the plan was strongly opposed not only by the moderados in the cortes, but also by the queen and General O'Donnell. Espartero's coalition with O'Donnell collapsed, and the queen named O'Donnell president of the government. He too proved unable to work with the government in any meaningful way; he attempted to compromise Espartero's constitution with the 1845 document by, in a bald assertion of power, declaring the 1845 constitution restored with certain specified exceptions, with or without the approval of the cortes. The act led to O'Donnell's ousting; the "Constitution of 1855" was never successfully put into place.

The end of the old order (1856–1868)

Once again, Ramón María Narváez, the symbol of reaction, returned to politics and was named president of the government by Isabella in 1856, who switched her favor to the moderados; Espartero, frustrated and bitter with political life, retired permanently to Logroño. Narváez's new government undid what little Espartero had been able to accomplish while in office; the Constitution of 1845 was restored in its entirety and the legislation that Espartero had put forward was entirely reversed in a matter of months. Isabella grew weary of this, too, and a moderate conservative with a less offensive authoritarian character was found in Francisco Armero Peñaranda, who took power in October 1857. Without Narváez's authoritarian touch, however, Peñaranda found that it was now as difficult for conservative policies to be successfully enacted by the cortes as it was for Espartero's progresista policies; the moderado faction was now divided, with some favoring O'Donnell's Unión Liberal ideal. Isabella then sacked Peñaranda – to the ire of the moderados – and replaced him with Francisco Javier Istúriz. Istúriz, though Isabella admired him, lacked any support from the conservative wing of the government, and was adamantly opposed by Bravo Murillo. Isabella was then disgusted with the moderados in any form; O'Donnell's faction was able to give the Unión Liberal another chance in 1858.

This government – the longest-lasting of all of Isabella's governments – lasted nearly five years before it was deposed in 1863. O'Donnell, reacting against the extremism that came from Espartero's government and the moderado governments that followed it, managed to pull some results from a functional Unión Liberal coalition of centrist, conciliatory moderados and progresistas, all of whom were exhausted from partisan bickering. O'Donnell's ministry was successful enough in restoring stability at home that they were able to project power abroad, which also helped to pull popular and political attention away from the cortes; Spain supported the French expedition to Cochinchina, the allied expedition sent in support of the French intervention in Mexico and Emperor Maximilian, an expedition to Santo Domingo, and most importantly, a successful campaign into Morocco that earned Spain a favorable peace and new territories across the Strait of Gibraltar. O'Donnell, even while president of the government, personally took command of the army in this campaign, for which he was named Duque de Tetuán. A new agreement was made with the Vatican in 1859 that reopened the possibility of legal desamortizaciones of church property. The previous year, Juan Prim, whilst a general, had either allowed Jews back onto Spanish territory for the first time since the Alhambra Decree in 1492,[1] or he would do so in 1868.[2][3]

The coalition broke apart in 1863 when old factional lines broke O'Donnell's cabinet: the issue of desamortización, brought up once again, antagonized the two wings of the Unión Liberal. The moderados, sensing an opportunity, attacked O'Donnell for being too liberal, and succeeded in turning the queen and cortes against him; his government collapsed on 27 February 1863.

The moderados immediately took to undoing O'Donnell's legislation but Spain's economic situation took a turn for the worse; when Alejandro Mon, who had already saved Spain's finances, proved ineffectual, Isabella turned to her old warhorse, Ramón Narváez, in 1864 to make certain that things did not get out of hand; this only infuriated the progresistas, who were promptly rewarded for their agitation by another O'Donnell government. General Juan Prim launched a major uprising against the government during O'Donnell's administration that prefigured future events; the rebellion was crushed brutally by O'Donnell, prompting the same sort of criticism that had toppled Espartero's government years earlier. The queen, listening to the opinion of the cortes, again sacked O'Donnell, and replaced him with Narváez, who had just been sacked two years earlier.

Narváez's support for the queen by this time was lukewarm; he had been sacked and seen enough governments thrown out by the queen in his lifetime that he, and much of the cortes had great doubts about her ability. The consensus spread; since 1854, a Republican party had been growing in strength, roughly in step with the fortunes of the Unión Liberal, and indeed, the Unión had been in coalition with the Republicans at times in the cortes.

La Gloriosa (1868–1873)

The 1866 rebellion led by Juan Prim and the revolt of the sergeants at San Gil sent a signal to Spanish liberals and republicans that there was serious unrest with the state of affairs in Spain that could be harnessed if it were properly led. Liberals and republican exiles abroad made agreements at Ostend in 1866 and Brussels in 1867. These agreements laid the framework for a major uprising, this time not merely to replace the president of the government with a liberal, but to overthrow Isabella herself, whom Spanish liberals and republicans began to see as the source of Spain's ineffectuality.

Her continual vacillation between liberal and conservative quarters had, by 1868, outraged moderados, progresistas, and members of the Unión Liberal and enabled, ironically, a front that crossed party lines. Leopoldo O'Donnell's death in 1867 caused the Unión Liberal to unravel; many of its supporters, who had crossed party lines to create the party initially, joined the growing movement to overthrow Isabella in favor of a more effective regime.

The die was cast in September 1868, when naval forces under admiral Juan Bautista Topete mutinied in Cadiz – the same place that Rafael del Riego had launched his coup against Isabella's father a half-century before. Generals Juan Prim and Francisco Serrano denounced the government and much of the army defected to the revolutionary generals on their arrival in Spain. The queen made a brief show of force at the Battle of Alcolea, where her loyal moderado generals under Manuel Pavía were defeated by General Serrano. Isabella then crossed into France and retired from Spanish politics to Paris, where she would remain until her death in 1904.

The revolutionary spirit that had just overthrown the Spanish government lacked direction; the coalition of liberals, moderates, and republicans were now faced with the incredible task of finding a government that would suit them better than Isabella. Control of the government passed to Francisco Serrano, an architect of the revolution against Baldomero Espartero's dictatorship. The cortes initially rejected the notion of a republic; Serrano was named regent while a search was launched for a suitable monarch to lead the country. A truly liberal constitution was written and successfully promulgated by the cortes in 1869 – the first such constitution in Spain since 1812.

The search for a suitable king proved to be quite problematic for the Cortes. The republicans were, on the whole, willing to accept a monarch if he was capable and abided by a constitution. Juan Prim, a perennial rebel against the Isabelline governments, was named chief of the government in 1869 and remarked that "to find a democratic king in Europe is as hard as to find an atheist in Heaven!" The aged Espartero was brought up as an option, still having considerable sway among the progresistas; even after he rejected the notion of being named king, he still gained eight votes for his coronation in the final tally. Many proposed Isabella's young son Alfonso (the future Alfonso XII of Spain), but many thought that he would invariably be dominated by his mother and would inherit her flaws. Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg, the former regent of neighboring Portugal, was sometimes raised as a possibility. A nomination offered to Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen would trigger the Franco-Prussian War.

In August 1870, an Italian prince, Amadeo of the House of Savoy, Duke of Aosta, was selected. The younger son of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, Amadeo had less of the troublesome political baggage that a German or French claimant would bring, and his liberal credentials were strong. He was duly elected King as Amadeo I of Spain on November 3, 1870. He landed in Cartagena on 27 November, the same day that Juan Prim was assassinated while leaving the Cortes. Amadeo swore upon the general's corpse that he would uphold Spain's constitution.

However, Amadeo had no experience as king, and what experience his father as King of Italy could offer was nothing compared to the extraordinary instability of Spanish politics. Amadeo was instantly confronted with a Cortes that regarded him as an outsider, even after it had elected him King; politicians conspired with and against him; and a Carlist uprising was taking place. In February 1873, he declared the people of Spain to be "ungovernable" and abandoned his kingdom, leaving rebel Republicans and Carlists to battle over the country.

Economic and social conditions

The loss of Spain's vast colonial empire greatly deprived the country of much wealth and it was soon reduced to one of Europe's poorest and least-developed nations. Over three-quarters of the population were illiterate and there was little industry except textile production in Catalonia. Although Spain possessed the iron and coal needed for industrial development, most was in the north and northeast and difficult to transport across the vast arid plain of the central Iberian Peninsula. Worsening matters were the lack of navigable rivers and a very rudimentary road network. British industrialists taught Spaniards how to extract iron ore while others studied the possibility of constructing a railroad system. Railroad pioneer George Stephenson, after conducting a survey of Spain, commented that "I have not seen enough people of the sort to fill even a single train." By the time a railroad network eventually got built, it merely radiated from Madrid outward and bypassed the major centers of natural resources.

High tariffs also dogged Spanish development, especially grain, of which imports were almost completely barred. The eastern provinces had to pay high costs for domestic cereals transported with the greatest difficulty across the peninsula while cheap Italian grain could have been easily imported from ship. Although Spain had been a major textile exporter in earlier times, the country could no longer compete with British and other producers and by the 19th century, most of its exports consisted of agricultural products. Catalonia was the only part of the country with any significant industry, but Castile remained the political and cultural center, barring major change.

See also

References

- Pierson, Peter (1999). The History of Spain. London: Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30272-3.

- Carr, Raymond (2000). Spain: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820619-4.

- Esdaile, Charles S. (2000). Spain in the Liberal Age: From Constitution to Civil War, 1808–1939. ISBN 0-631-14988-0.

- Gallardo, Alexander (1978). Britain and the First Carlist War. Darby, PA: Norwood Editions.

- ↑ Jews in Spain in the Second Half of the Fifteenth Century

- ↑ The Jewish Virtual History Tour: Spain

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=BNWvt4i2NRIC&pg=PA12&lpg=PA12&dq=juan+prim+jews&source=bl&ots=tYWnofIZSc&sig=rBnLHPkhPOyJ9TUaU3xWV3LOsxw&hl=en&ei=4viRSqL9E9HclAfG5PWjDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2#v=onepage&q=juan%20prim%20jews&f=false The Spanish Right and the Jews, 1898-1945: Antisemitism and Opportunism

Further reading

- Bowen, Wayne H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0826219381. OCLC 711050963.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

_Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png)