History of Solomon Islands

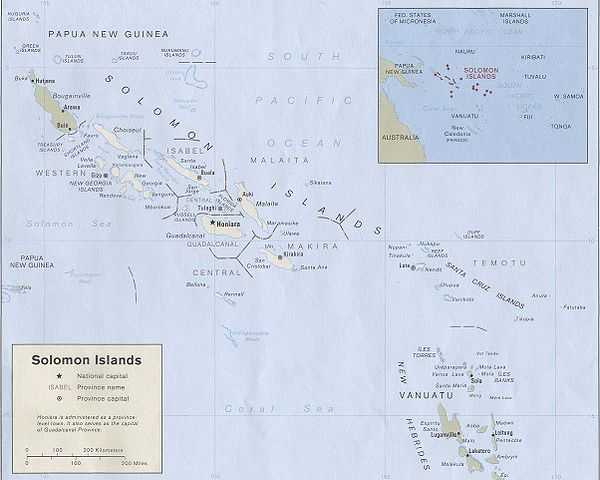

Solomon Islands is a sovereign state in the Melanesia subregion of Oceania in the western Pacific Ocean. This page is about the history of the nation state rather than the broader geographical area of the Solomon Islands archipelago, which covers both Solomon Islands and Bougainville Island, a province of Papua New Guinea. For the history of the archipelago not covered here refer to the former administration of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, the North Solomon Islands and the History of Bougainville.

Earliest inhabitants

The human history of Solomon Islands begins with the first Papuan settlement at least 30,000 years ago from New Guinea. They represented the furthest expansion of humans into the Pacific until the expansion of Austronesian-language speakers through the area around 4000 BC, bringing new agricultural and maritime technology. Most of the languages spoken today in Solomon Islands derive from this era, but some thirty languages of the pre-Austronesian settlers survive (see East Papuan languages).

There are preserved numerous pre-European cultural monuments in Solomon Islands, notably Bao megalithic shrine complex (13th century AD), Nusa Roviana fortress and shrines (14th - 19th century), Vonavona Skull island - all in Western province. Nusa Roviana fortress, shrines and surrounding villages served as a hub of regional trade networks in 17th - 19th centuries. Skull shrines of Nusa Roviana are sites of legends. Better known is Tiola shrine - site of legendary stone dog which turned towards the direction where enemy of Roviana was coming from.[1] This complex of archaeological monuments characterises fast development of local Roviana culture, through trade and head hunting expeditions turning into regional power in 17th - 18th centuries.[2]

European contact

Ships of the Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira first sighted Santa Isabel island on 6 February 1568. Finding signs of alluvial gold on Guadalcanal, Mendaña believed he had found the source of King Solomon's wealth, and consequently named the islands "The Islands of Solomon".

In 1595 and 1605 Spain again sent several expeditions to find the islands and establish a colony, however these were unsuccessful. In 1767 Captain Philip Carteret rediscovered the Santa Cruz Islands and Malaita. Later, Dutch, French and British navigators visited the islands; their reception was often hostile.

Colonization

Sikaiana, then known as the Stewart Islands, was annexed to the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1856. Hawai'i did not formalize the annexation, and the United States refused to recognize Hawaiian sovereignty over Sikaiana when the United States annexed Hawai'i in 1898.

Missionary activity then started at the mid 19th century and European colonial ambitions led to the establishment of a German Protectorate over the North Solomon Islands, which covered parts of what is now Solomon Islands, following an Anglo-German Treaty of 1886. A British Solomon Islands Protectorate over the southern islands was proclaimed in June 1893. German interests were transferred to the United Kingdom under the Samoa Tripartite Convention of 1899, in exchange for recognition of the German claim to Western Samoa.

World War II

Japanese forces occupied the Solomon Islands in January 1942. The counter-attack was led by the United States; the 1st Division of the US Marine Corps landed on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August 1942. Some of the most bitter fighting of World War II took place on the islands for almost three years.

Tulagi, the seat of the British administration on the island of Nggela Sule in Central Province was destroyed in the heavy fighting following landings by the US Marines. Then the tough battle for Guadalcanal, which was centred on the capture of the airfield, Henderson field, led to the development of the adjacent town of Honiara as the United States logistics centre.

Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana

Islanders Biuku Gasa (deceased 2005) and Eroni Kumana (Gizo) were Allies scouts during the war. They became famous when they were noted by National Geographic for being the first men to find the shipwrecked John F. Kennedy and his crew of the PT-109 using a traditional dugout canoe. They suggested the idea of using a coconut which was later kept on the desk of the president to write a rescue message for delivery. Their names had not been credited in most movie and historical accounts, and they were turned back before they could visit President Kennedy's inauguration, though the Australian coastwatcher would also meet the president. They were visited by a member of the Kennedy family in 2002, where they lived in traditional huts without electricity.

War consequences

The impact of the war on islanders was profound. The destruction caused by the fighting and the longer-term consequences of the introduction of modern materials, machinery and western cultural artefacts, transformed traditional isolated island ways of life. The reconstruction was slow in the absence of war reparations and with the destruction of the pre-war plantations, formerly the mainstay of the economy. Significantly, Solomon Islanders experience as labourers with the Allies led some to a new appreciation of the importance of economic organisation and trade as the basis for material advancement. Some of these ideas were put into practice in the early post-war political movement "Maasina Ruru" - often corrupted to "Marching Rule".17

Post war (1945-1978)

Stability was restored during the 1950s, as the British colonial administration built a network of official local councils. On this platform Solomon Islanders with experience on the local councils started participation in central government, initially through the bureaucracy and then, from 1960, through the newly established Legislative and Executive Councils. Positions on both Councils were initially appointed by the High Commissioner of the British Protectorate but progressively more of the positions were directly elected or appointed by electoral colleges formed by the local councils. The first national election was held in 1964 for the seat of Honiara, and by 1967 the first general election was held for all but one of the 15 representative seats on the Legislative Council (the one exception was the seat for the Eastern Outer Islands, which was again appointed by electoral college).

Elections were held again in 1970 and a new constitution was introduced. The 1970 constitution replaced the Legislative and Executive Councils with a single Governing Council. It also established a 'committee system of government' where all members of the Council sat on one or more of five committees. The aim of this system was to reduce divisions between elected representatives and the colonial bureaucracy, provide opportunities for training new representatives in managing the responsibilities of government.

It was also claimed that this system was more consistent with the Melanesian style of government, however this was quickly undermined by opposition to the 1970 constitution and the committee system by elected members of the council. As a result, a new constitution was introduced in 1974 which established a standard Westminster form of government and gave the Islanders both Chief Ministerial and Cabinet responsibilities. Solomon Mamaloni became the country's first Chief Minister in July 1974.

Independence (1978)

As late as 1970, the British Protectorate did not envisage independence for Solomon Islands in the foreseeable future. Shortly thereafter, the financial costs of supporting the Protectorate became more trying, as the world economy was hit by the first oil price shock of 1973. The imminent independence of Papua New Guinea (in 1975) was also thought to have influenced the Protectorate's administrators.

Outside of a very small educated elite in Honiara, there was little in the way of an indigenous independence movement in the Solomons. Self-government was granted in January 1976 and after July 1976, Sir Peter Kenilorea became the Chief Minister who would lead the country to independence. Independence was granted on 7 July 1978, and Kenilorea automatically became the country's first Prime Minister.

Ethnic violence (1999-2003)

In early 1999 long-simmering tensions between the local Gwale people on Guadalcanal and more recent migrants from the neighbouring island of Malaita erupted into violence. The ‘Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army’, later called Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM), began terrorising Malaitans in the rural areas of the island to make them leave their homes. About 20,000 Malaitans fled to the capital and others returned to their home island; Gwale residents of Honiara fled. The city became a Malaitan enclave.

Meanwhile, the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF) was formed to uphold Malaitan interests. The Government appealed to the Commonwealth Secretary General for assistance. The Honiara Peace Accord was agreed on 28 June 1999. Despite this apparent success the underlying problems remained unresolved and had already resulted in the death or serious injury of 30,000 civilians. The accord soon broke down and fighting broke out again in June 2000.

Malaitans took over some armouries at their home island and Honiara and helped by that, on 5 June 2000 the MEF seized the parliament by force. Through their spokesman Andrew Nori, they claimed that the government of the then Prime Minister, Bartholomew Ulufa'alu, had failed to secure compensation for loss of Malaitan life and property. Ulufa’alu was forced to step down.

On 30 June 2000 Parliament elected by a narrow margin a new Prime Minister, Manasseh Sogavare. He established a Coalition for National Unity, Reconciliation and Peace, which released a program of action focused on resolving the ethnic conflict, restoring the economy and distributing the benefits of development more equally. However, Sogavare’s government was deeply corrupt and its actions led to the downward economic spiral and the deterioration of law and order.

The conflict was foremost about access to land and other resources and was centered around Honiara. Since the beginning of the civil war it is estimated that 100 have been killed. About 30,000 refugees, mainly Malaitans, had to leave their homes, and economic activity on Guadalcanal was severely disrupted.

Continuing civil unrest led to an almost complete breakdown in normal activity: civil servants remained unpaid for months at a time, and cabinet meetings had to be held in secret to prevent local warlords from interfering. The security forces were unable to reassert control, largely because many police and security personnel are associated with one or another of the rival gangs.

In July 2003 the Governor General of Solomon Islands issued an official request for international help, which was subsequently endorsed by a unanimous vote of the parliament. Technically, only the Governor General's request for troops was necessary. However, the government then passed legislation to provide the international force with greater powers and resolve some legal ambiguities.

On 6 July 2003, in response to a proposal to send 300 police and 2,000 troops from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Papua New Guinea to Guadalcanal, warlord Harold Keke announced a ceasefire by faxing a signed copy of the announcement to the Solomons Prime Minister, Allan Kemakeza. Keke ostensibly leads the Guadalcanal Liberation Front, but has been described as marauding bandit based on the isolated southwestern coast (Weather Coast) of Guadalcanal. Despite this ceasefire, on 11 July 2003 the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation broadcast unconfirmed reports that supporters of Harold Keke razed two villages.

In mid-July 2003, the Solomons parliament voted unanimously in favour of the proposed intervention. The international force began gathering at a training facility in Townsville. In August 2003, an international peacekeeping force, known as the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) and Operation Helpem Fren, entered the islands. Australia committed the largest number of security personnel, but with substantial numbers also from other South Pacific Forum countries such as New Zealand, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea (PNG). It acts as an interim police force and is responsible for restoring law and order in the country because the Royal Solomon Islands Police force failed to do so for a variety of reasons. Peacekeeping forces have been successful in improving the country's overall security conditions, including brokering the surrender of a notorious warlord Harold Keke in August 2003.

In 2009, the government is scheduled to set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with the assistance of South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, to "address people’s traumatic experiences during the five year ethnic conflict on Guadalcanal".[3][4]

The government continues to face serious problems, including an uncertain economic outlook, deforestation, and malaria control. At one point, prior to the deployment of RAMSI forces, the country was facing a serious financial crisis. While economic conditions are improving, the situation remains unstable.

Cyclones

In 1992, Cyclone Tia struck the island of Tikopia, wiping out most housing and food crops. In 1997, the Government asked for help from the USA and Japan to clean up more than 50 sunken World War II shipwrecks polluting coral reefs and killing marine life.

In December 2002, Severe Tropical Cyclone Zoe struck the island of Tikopia and Anuta, cutting off contact with the 3,000 inhabitants. Due to funding problems, the Solomon Islands government could not send relief until the Australian government provided funding.

Cyclone Ita

In April 2014 the islands were struck by the tropical low that later became Cyclone Ita.

Throughout the Solomons, at least 23 people were killed while up to 40 others remained unaccounted for as of 6 April. An estimated 49,000 people were affected by the floods, of whom 9,000 were left homeless.[5][6]

As the precursor tropical low to Ita affected the Islands, local authorities issued heavy flood warnings, tropical disturbance and cyclone watches.[7]

Nearly two days of continuous heavy rains from the storm caused flash flooding in the Islands.[8] Over a four-day span, more than 1,000 mm (39 in) fell at the Gold Ridge mine in Guadalcanal, with 500 mm (20 in) falling in a 24 hour-span.[9] The Matanikau River, which runs through the capital city Honiara, broke its banks on 3 April and devastated nearby communities. Thousands of homes along with the city's two main bridges were washed away, stranding numerous residents.[8] The national hospital had to evacuate 500 patients to other facilities due to flooding.[10] Graham Kenna from Save the Children stated that, "the scale of destruction is like something never seen before in the Solomon Islands."[11] According to Permanent Secretary Melchoir Mataki, the majority of homes destroyed in Honiara were built on a flood plain where construction was not allowed.[5]

Severe flooding took place on Guadalcanal.[8] Immediately following the floods, Honiara and Guadalcanal were declared disaster areas by the Solomon Government.[12] Debris left behind by the floods initially hampered relief efforts, with the runway at Honiara International Airport blocked by two destroyed homes. Food supplies started running low as the Red Cross provided aid to the thousands homeless. The airport was reopened on 6 April, allowing for supplies from Australia and New Zealand to be delivered.[6] Roughly 20 percent of Honiara's population relocated to evacuation centers as entire communities were swept away.[13] There were fears that the flooding could worsen an already ongoing dengue fever outbreak and cause outbreaks of diarrhea and conjunctivitis.[5]

New Zealand offered an immediate NZ$300,000 in funds and deployed a C-130 Hercules with supplies and emergency response personnel.[13] Australia donated A$250,000 on 6 April and sent engineers and response teams to aid in relief efforts.[14] On 8 April, Australia increased its aid package to A$3 million while New Zealand provided an additional NZ$1.2 million.[5][15] Taiwan provided US$200,000 in funds.[16]

On 4 April (5 April local time[8]) a 6.0 MW earthquake, with its epicenter on Makira island, struck the Islands.[17] Though no reports of damage were received in relation to it, officials were concerned about possible landslides.[8]

See also

- History of Oceania

- List of Prime Ministers of Solomon Islands

- Politics of Solomon Islands

References

- ↑ "Nusa Roviana hillfort and shrines". Wondermondo.

- ↑ Peter J. Sheppard, Richard Walter, Takuya Nagaoka. "The Archaeology of Head-Hunting in Roviana Lagoon, New Georgia". The Journal of Polynesian Society.

- ↑ "Solomon Islands moves closer to establishing truth and reconciliation commission". Radio New Zealand International. 4 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ "Archbishop Tutu to Visit Solomon Islands", Solomon Times, 4 February 2009

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Sean Dorney (8 April 2014). "Solomon Islands National Disaster Council issues all clear in wake of deadly Honiara floods". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Solomon Islands floods: search continues for missing". Sydney Morning Herald. Agence France-Presse. 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ http://www.pacificdisaster.net/pdnadmin/data/original/SLB_FL_20140403__Homes_inundated.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Michael Field (5 April 2014). "Kiwis join Solomons flood clean up". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ "Future of Gold Ridge Mining Uncertain After Floods". Solomon Times Online. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "Solomon Islands Humanitarian Situation Report #1, 1- 4 April 2014" (PDF). United Nations Children's Fund. ReliefWeb. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ "Fears for deadly outbreak of dengue fever in flood and quake hit Solomons". Save the Children. ReliefWeb. 5 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ "OCHA Flash Update 1: Solomon Islands Flash Floods, 4 April 2014". United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. ReliefWeb. 5 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rebecca Quilliam; Audrey Young (6 April 2014). "Solomon Islands disaster: Thousands left homeless". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ "Aust boosts aid to flooded Solomon Islands". 9 News. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ "NZ sends aid after Solomon Islands deadly floods". ONE News. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ Elaine Hou (8 April 2014). "Taiwan donates US$200,000 to flood-ravaged Solomon Islands". Focus Taiwan. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "M6.0 - 28km WSW of Kirakira, Solomon Islands". United States Geological Survey. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

Further reading

- Miller, Jr., John (1995) [1949]. Guadalcanal: The First Offensive. United States Army in World War II The War in the Pacific. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 5-3.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||