History of Punic-era Tunisia: culture

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Tunisia | ||||||||||||

| Prehistory | ||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

| Early modern | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Modern | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Tunisia portal | ||||||||||||

History of Punic-era Tunisia: culture addresses various institutions and social organizations created by the people of the city-state of Carthage and surrounding regions. Very few Punic writings from that era survived. Most of existing written works that discuss civic and religious life in Punic-era Carthage come from Greek and Roman authors, whose own people were generally hostile to Carthage.

Finding evidence of Punic-era Carthage is very difficult, due to the severe damage suffered by the city during the Third Punic War, followed by its wholesale reconstruction during Roman times. From ancient written descriptions and from meager on-site findings, certain features of the ancient city are known or surmised, as well as the rural life-style and culture of the people living on the nearby agricultural lands.

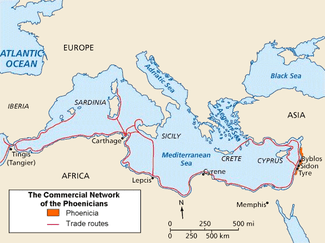

Carthage was originally founded as a Phoenician base for Mediterranean-wide trade, and was renowned among contemporaries for its great prosperity. Cooperative commercial ventures organized the creation of this wealth. Urban industries produced many of the commodities sold or bartered. Key was the city's far-flung trading empire, backed by the maritime power of the state. Ships and crews were largely run by family-operated companies, functioning among wider merchant associations.

The constitution of the city-state of Carthage drew admiring commentary by foreigners, including Aristotle, the Greek philosopher of the 4th century BCE. The city-state's government at the time had already undergone significant developments since the first state institutions of earliest Carthage. The city at its founding was probably based on Phoenician models. Aristotle describes the unique constitution of Carthage in terms of the political thinking of the ancient Greeks, yet ancient sources leave many questions unanswered, allowing room for differing interpretations of its history.

The Punic religion also had its origins in Phoenicia, which shared several Semitic features in common with the religious history of its neighbor Ancient Israel, although with significant differences. As religion at Carthage developed in its new African environment, some mutual influences arose between the Punic and the native Berber views of worship and deity. Carthaginians understood themselves as a religious people. At the peak of the city's fame and prosperity, Tanit was recognized as the queen goddess of Carthage.[1]

Extant writings

Most ancient literature concerning Carthage comes from Greek and Roman sources. Considering the rivalry of the political-economies of Hellenic Sicily versus Carthage, and of Republican Rome versus Carthage, it is not surprising that both Greek and Roman authors generally viewed Carthage as an antagonist. Only in this light may many of the subtleties of the Punic city's history and culture be perceived, that is, as illuminated by various ancient Greek and Roman commentators.[2][3]

Apart from inscriptions, hardly any Punic literature has survived, and none in its own language and script.[4] A brief catalogue would include:[5]

- three short treaties with Rome (Latin translations);[6][7][8]

- several pages of Hanno the Navigator's log-book concerning his fifth century maritime exploration of the Atlantic coast of west Africa (Greek translation);[9]

- fragments quoted from Mago's fourth/third century 28-volume treatise on agriculture (Latin translations);[10][11]

- the Roman playwright Plautus (c. 250 – 184) in his Poenulus incorporates a few fictional speeches delivered in Punic, whose written lines are transcribed into Latin letters phonetically;[12][13]

- the thousands of inscriptions made in Punic script, thousands, but many extremely short, e.g., a dedication to a deity with the personal name(s) of the devotee(s).[14][15]

"[F]rom the Greek author Plutarch [(c. 46 – c. 120)] we learn of the 'sacred books' in Punic safeguarded by the city's temples. Few Punic texts survive, however."[16] Once "the City Archives, the Annals, and the scribal lists of suffets" existed, but evidently these were destroyed in the horrific fires during the Roman capture of the city in 146 BC.[17]

Yet some Punic books (Latin: libri punici) from the libraries of Carthage reportedly did survive the fires.[18] These works were apparently given by Roman authorities to the newly augmented Berber rulers.[19][20] Over a century after the fall of Carthage, the Roman politician-turned-author Gaius Sallustius Crispus or Sallust (86–34) reported his having seen volumes written in Punic, which books were said to be once possessed by the Berber king, Hiempsal II (r. 88–81).[21][22][23] By way of Berber informants and Punic translators, Sallust had used these surviving books to write his brief sketch of Berber affairs.[24][25]

Probably some of Hiempsal II's libri punici, that had escaped the fires that consumed Carthage in 146 BC, wound up later in the large royal library of his grandson Juba II (r.25 BC-AD 24).[26] Juba II not only was a Berber king, and husband of Cleopatra's daughter, but also a scholar and author in Greek of no less than nine works.[27] He wrote for the Mediterranean-wide audience then enjoying classical literature. The libri punici inherited from his grandfather surely became useful to him when composing his Libyka, a work on North Africa written in Greek. Unfortunately, only fragments of Libyka survive, mostly from quotations made by other ancient authors.[28] It may have been Juba II who 'discovered' the five-centuries-old 'log book' of Hanno the Navigator, called the Periplus, among library documents saved from fallen Carthage.[29][30][31]

In the end, however, most Punic writings that survived the destruction of Carthage "did not escape the immense wreckage in which so many of Antiquity's literary works perished."[32] Accordingly, the long and continuous interactions between Punic citizens of Carthage and the Berber communities that surrounded the city have no local historian. Their political arrangements and periodic crises, their economic and work life, the cultural ties and social relations established and nourished (infrequently as kin), are not known to us directly from ancient Punic authors in written accounts. Neither side has left us their stories about life in Punic-era Carthage.[33]

Regarding Phoenician writings, few remain and these seldom refer to Carthage. The more ancient and most informative are cuneiform tablets, ca. 1600–1185, from ancient Ugarit, located to the north of Phoenicia on the Syrian coast; it was a Canaanite city affiliated with the Hittites. The clay tablets tell of myths, epics, rituals, medical and administrative matters, and also correspondence.[34][35][36] The highly valued works of Sanchuniathon, an ancient priest of Beirut, who reportedly wrote on Phoenician religion and the origins of civilization, are themselves completely lost, but some little content endures twice removed.[37][38] Sanchuniathon was said to have lived in the 11th century, which is considered doubtful.[39][40] Much later a Phoenician History by Philo of Byblos (64–141) reportedly existed, written in Greek, but only fragments of this work survive.[41][42] An explanation proffered for why so few Phoenician works endured: early on (11th century) archives and records began to be kept on papyrus, which does not long survive in a moist coastal climate.[43] Also, both Phoenicians and Carthaginians were well known for their secrecy.[44][45]

Thus, of their ancient writings we have little of major interest left to us by Carthage, or by Phoenicia the country of origin of the city founders. "Of the various Phoenician and Punic compositions alluded to by the ancient classical authors, not a single work or even fragment has survived in its original idiom." "Indeed, not a single Phoenician manuscript has survived in the original [language] or in translation."[46] We cannot therefore access directly the line of thought or the contour of their worldview as expressed in their own words, in their own voice.[47] Ironically, it was the Phoenicians who "invented or at least perfected and transmitted a form of writing [the alphabet] that has influenced dozens of cultures including our own."[48][49][50]

As noted, the celebrated ancient books on agriculture written by Mago of Carthage survives only via quotations in Latin from several later Roman works. His books are discussed in the City and country section below.

City and country

The original Punic settlements here were merely enclaves, started to service the trans-Mediterranean trading network created by the Phoenician mother-city, Tyre. The merchant harbor at Carthage was developed, after settlement of the nearby Punic town of Utica.[51] Eventually the surrounding countryside was brought into the orbit of the Punic urban centers, first commercially, then politically. Direct management over cultivation of neighboring lands by Punic owners followed.[52]

A widely admired, 28-volume work on agriculture was authored in Punic by Mago (c. 300). After the fall of Carthage (in 146), it was translated into Latin by Decimus Silanus (a Roman expert in the Punic language), and later into Greek; yet the original and both translations were lost. Mago's text, however, was quoted in Latin by Varro (116–27), a acclaimed Roman polymath, in his De re rustica, and by Columella (1st century AD), a Roman writer on agriculture. Mago was praised by Pliny the Elder (23–79), the Roman encyclopedist, for his knowledge of farming techniques.[53][54] Mago was known to be a retired army general. Olive trees (e.g., grafting), fruit trees (pomegranate,[55] almond, fig, date palm), viniculture, bees, cattle, sheep, poultry, implements, and farm management were among the ancient topics which Mago discussed. As well, Mago addresses the wine-maker's art (here a type of sherry).[56][57][58]

In Punic farming society, according to Mago, the small estate owners were the chief producers. They were, two modern historians write, not absent landlords. Rather, the likely reader of Mago was "the master of a relatively modest estate, from which, by great personal exertion, he extracted the maximum yield." Mago counseled the rural landowner, for the sake of their own 'utilitarian' interests, to treat carefully and well their managers and farm workers, or their overseers and slaves.[59] Yet elsewhere these writers suggest that rural land ownership provided also a new power base among the city's nobility, for those resident in their country villas.[60][61] By many, farming was viewed as an alternative endeavor to an urban business. Another modern historian opines that more often it was the urban merchant of Carthage who owned rural farming land to some profit, and also to retire there during the heat of summer.[62] It may seem that Mago anticipated such an opinion, and instead issued this contrary advice (as quoted by the Roman writer Columella):

"The man who acquires an estate must sell his house, lest he prefer to live in the town rather than in the country. Anyone who prefers to live in a town has no need of an estate in the country."[63] "One who has bought land should sell his town house, so that he will have no desire to worship the household gods of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes greater delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate."[64]

The issues involved in rural land management also reveal underlying features of Punic society, its structure and stratification. The hired workers might be considered 'rural proletariate', drawn from the local Berbers.[65] Whether or not there remained Berber landowners next to Punic-run farms is unclear. Some Berbers became sharecroppers. Slaves acquired for farm work were often prisoners of war. In lands outside Punic political control, independent Berbers cultivated grain and raised horses on their lands. Yet within the Punic domain that surrounded the city-state of Carthage, there were ethnic divisions in addition to the usual quasi feudal distinctions between lord and peasant, or master and serf. This inherent instability in the countryside drew the unwanted attention of potential invaders.[66] Yet for long periods Carthage was able to manage these social difficulties.[67]

The many amphorae with Punic markings subsequently found about ancient Mediterranean coastal settlements testify to Carthaginian trade in locally made olive oil and wine.[68] Carthage's agricultural production was held in high regard by the ancients, and rivaled that of Rome—they were once competitors, e.g., over their olive harvests. Under Roman rule, however, grain production (corn and barley) for export increased dramatically in 'Africa'; yet these later fell with the rise in Roman Egypt's grain exports. Thereafter olive groves and vineyards were re-established around Carthage. Visitors to the several growing regions that surrounded the city wrote admiringly of the lush green gardens, orchards, fields, irrigation channels, hedgerows (as boundaries), as well as the many prosperous farming towns located across the rural landscape.[69][70]

Accordingly, the Greek author and compilor Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BCE), who enjoyed access to ancient writings later lost, and on which he based most of his writings, described agricultural land near the city of Carthage circa 310 BC:

"It was divided into market gardens and orchards of all sorts of fruit trees, with many streams of water flowing in channels irrigating every part. There were country homes everywhere, lavishly built and covered with stucco. ... Part of the land was planted with vines, part with olives and other productive trees. Beyond these, cattle and sheep were pastured on the plains, and there were meadows with grazing horses."[71][72]

The Chora (farm lands of Carthage) encompassed a limited area: the north coastal tell, the lower Bagradas river valley (inland from Utica), Cape Bon, and the adjacent sahel on the east coast. Punic culture here achieved the introduction of agricultural sciences first developed for lands of the eastern Mediterranean, and their adaptation to local African conditions.[73]

The urban landscape of Carthage is known in part from ancient authors,[74] augmented by modern digs and surveys conducted by archeologists. The "first urban nucleus" dating to the seventh century, in area about ten hectares (or four acres), was apparently located on low lying lands along the coast (north of the later harbors). As confirmed by archaeological excavations, Carthage was a "creation ex nihilo," built on 'virgin' land, and situated at the end of a peninsula (per the ancient coastline). Here among "mud brick walls and beaten clay floors" (recently uncovered) were also found extensive cemeteries, which yielded evocative grave goods, e.g., clay masks. "Thanks to this burial archaeology we know more about archaic Carthage than about any other contemporary city in the western Mediterranean." Already in the eighth century fabric dyeing operations had been established, evident from crushed shells of murex (from which the 'Phoenician purple'). Nonetheless only a "meager picture" of the cultural life of the earliest pioneers in the city can be conjectured, and nothing about housing, nor monuments, nor defenses.[75][76] The Roman poet Virgil imagined early Carthage, when his legendary character Aeneas arrived there:

"Aneneas found, where lately huts had been,marvelous buildings, gateways, cobbled ways, and din of wagons. There the Tyrians were hard at work: laying courses for walls, rolling up stones to build the citadel, while others picked out building sites and plowed a boundary furrow. Laws were being enacted, magistrates and a sacred senate chosen. Here men were dredging harbors, there they laid the deep foundations of a theatre,

and quarried massive pillars... ."[77][78]

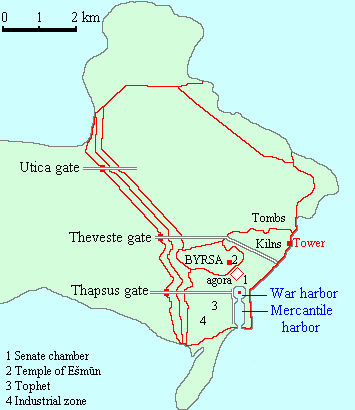

What follows here is a description most appropriate to the city-state of Carthage, circa 150 BC (just before the Third Punic War in which it was destroyed), with some mention of the city's earlier stages.[79] The two inner harbors [called in Punic cothon] were located in the southeast; one being commercial, and the other for war. Their definite functions are not entirely known, probably for the construction, outfitting, or repair of ships, perhaps also loading and unloading cargo.[80][81][82] Larger anchorages existed to the north and south of the city.[83] North and west of the cothon were located several industrial areas, e.g., metalworking and pottery (e.g., for amphora), which could serve both inner harbors, and ships anchored to the south of the city.[84]

About the Byrsa, the citadel area to the north,[85] considering its importance our knowledge of it is patchy, due to the fiery fall of the city in 146. The Byrsa heights were the reported site of the Temple of Eshmun (the healing god), at the top of a stairway of sixty steps.[86][87] A temple of Tanit (the queen goddess) was likely situated on the slope of the 'lesser Byrsa' immediately to the east.[88] Also situated on the Byrsa were luxury homes.[89]

South of the citadel, near the cothon, the inner harbors, was the tophet, a special and very old cemetery, which when begun lay outside the city's boundaries. Here the Salammbô was located, the Sanctuary of Tanit, not a temple but an enclosure for placing stone stelae. Evidence from here may indicate the occurrence of child sacrifice. Probably it was "dedicated at an early date, perhaps by the first settlers."[90][91]

Between the sea-filled cothon for shipping and the Byrsa heights lay the agora [Greek: "market"], i.e., the central marketplace for business and commerce. The agora was also an area of public squares and plazas, where the people might formally assemble, or gather for festivals. It was the site of religious shrines, and the location of whatever were the major municipal buildings of Carthage. Here beat the heart of civic life. In this district of the city-state, more probably, the ruling suffets presided, the council of elders convened, the tribunal of the 104 met, and justice was dispensed at trials in the open air.[92][93]

Early residential districts wrapped around the Byrsa from the south to the north east. Houses usually were whitewashed and blank to the street, but within were courtyards open to the sky.[94] In these neighborhoods multistory construction later became common, some up to six stories tall according to an ancient Greek author.[95][96] Several architecutural floorplans of homes have been revealed by recent excavations, as well as the general layout of several city blocks. Stone stairs were set in the streets, and drainage was planned, e.g., in the form of soakways leaching into the sandy soil.[97] Along the Byrsa's southern slope were located not only fine old homes, but also many of the earliest gravesites, interspersed with the living, juxtaposed.[98]

Artisan workshops were located in the city at sites north and west of the harbors. The location of three metal workshops (implied from iron slag and other vestiges of such activity) were found adjacent to the naval and commercial harbors, and another two were further up the hill toward the Byrsa citadel. Sites of pottery kilns have been identified, between the agora and the harbors, and further north. Earthenware often used Greek models. A fuller's shop for preparing woolen cloth (shrink and thicken) was evidently situated further to the west and south, then by the edge of the city.[99] Carthage also produced very refined objects. During the 4th and 3rd centuries, the sculptures of the sarcophagi became works of art. "Bronze engraving and stone-carving reached their zenith."[100]

The elevation of the land at the promontory on the seashore to the northeast (now called Sidi Bou Saïd), was twice as high above sea level as that at the Byrsa (roughly 100 meters versus 50). In between runs a ridge that several times reaches 50 meters; this ridge continues northward along the seashore, and forms the edge of a plateau-like area between the Byrsa and the sea).[101] Newer urban developments lay here in these northern districts.[102]

Surrounding Carthage were walls "of great strength" said in places to rise above forty feet (13 m), being nearly thirty feet (10 m) thick, according to ancient authors. To the west three parallel walls were built. The walls altogether ran for about thirty-three kilometers to encircle the city.[103][104] The heights of the Byrsa were additionally fortified; this area being the last to succumb to the Romans in 146 BC. The Romans had landed their army on the strip of land extending southward from the city.[105][106]

Trade and business

Maritime trade was the original raison d'être of the city, its commercial lifeblood. Carthage, of course, drew upon the business experience, the range of commodities, and the navigation lore of the Phoenicians. To distinguish: Phoenicia excelled more as a trading nation, than as producers of goods for sale. Yet they crafted quality textiles, including the development of a purple dye from marine life [the murex shellfish], which became famous throughout the ancient Mediterranean for its regal color and endurance (fade resistance).[107] Jewelry, glass, and ceramics were also fabricated and entered the flow of commerce.[108] Later, agricultural products were added.[109] Yet at the beginning of their Mediterranean ventures, which led to the founding of Carthage, the Phoenicians had "travelled westward not as true colonists but as traders." [110]

In establishing commercial relations with native peoples, communication became an issue due to language differences, especially in more distant and less developed lands along the western Mediterranean and Atlantic. To be avoided was any chance of armed conflict, which was bad for business. The Phoenicians, and later the merchants of Carthage, came to use a procedure of silent barter. The Greek author Herodotus (born in 484 BC) wrote that it was employed in Africa (for example, among "Libyans beyond the Pillars of Heracles"), where gold dust was used in trade. Herodotus in his Istorion tells us of the way it was done—which is here summarized:[111][112]

Merchants took their ship-borne wares and placed them on the beach for inspection, then withdrew to "raise a smoke". Locals would come to see and, beside the goods desired, leave an amount of gold; then withdraw. The traders would return, and if a "fair price" take it; otherwise, they would withdraw again. The local then might add more gold, and so back and forth. There was, wrote the ancient Greek, "perfect honesty" on both sides.[113]

The merchants of Carthage were in part heirs of the Mediterranean trade developed by Phoenicia, and so also heirs of the rivalry with Greek merchants. Business activity was accordingly both stimulated and challenged. Cyprus had been an early site of such commercial contests. The Phoenicians then had ventured into the western Mediterranean, founding trading posts, including Utica and Carthage. The Greeks followed, entering the western seas where the commercial rivalry continued. Eventually it would lead, especially in Sicily, to several centuries of intermittent war.[114][115]

Although Greek-made merchandise was generally considered superior in design, Carthage also produced trade goods in abundance. That Carthage came to function as a manufacturing colossus was shown during the Third Punic War with Rome. Carthage, which had previously disarmed, then was made to face the fatal Roman siege. The city "suddenly organised the manufacture of arms" with great skill and effectiveness. According to Strabo (63 BC – AD 21) in his Geographica:

"[Carthage] each day produced one hundred and forty finished shields, three hundred swords, five hundred spears, and one thousand missiles for the catapults... . Furthermore, [Carthage although surrounded by the Romans] built one hundred and twenty decked ships in two months... for old timber had been stored away in readiness, and a large number of skilled workmen, maintained at public expense."[116]

The textiles industry in Carthage probably started in private homes, but the existence of professional weavers indicates that a sort of factory system later developed. Products included embroidery, carpets, and use of the purple murex dye (for which the Carthaginian isle of Djerba was famous). Metalworkers developed specialized skills, i.e., making various weapons for the armed forces, as well as domestic articles, such as knives, forks, scissors, mirrors, and razors (all articles found in tombs). Artwork in metals included vases and lamps in bronze, also bowls, and plates. Other products came from such crafts as the potters, the glassmakers, and the goldsmiths. Inscriptions on votive stele indicate that many were not slaves but 'free citizens'.[117]

Phoenician and Punic merchant ventures were often run as a family enterprise, putting to work its members and its subordinate clients. Such family-run businesses might perform a variety of tasks: (a) own and maintain the ships, providing the captain and crew; (b) do the negotiations overseas, either by barter or buy and sell, of (i) their own manufactured commodities and trade goods, and (ii) native products (metals, foodstuffs, etc.) to carry and trade elsewhere; and (c) send their agents to stay at distant outposts in order to make lasting local contacts, and later to establish a warehouse of shipped goods for exchange, and eventually perhaps a settlement. Over generations, such activity might result in the creation of a wide-ranging network of trading operations. Ancillary would be the growth of reciprocity between different family firms, foreign and domestic.[118][119]

State protection was extended to its sea traders by the Phoenician city of Tyre and later likewise by the daughter city-state of Carthage.[120] Stéphane Gsell, the well-regarded French historian of ancient North Africa, summarized the major principles guiding the civic rulers of Carthage with regard to its policies for trade and commerce:

- (1) to open and maintain markets for its merchants, whether by entering into direct contact with foreign peoples using either treaty negotiations or naval power, or by providing security for isolated trading stations;

- (2) the reservation of markets exclusively for the merchants of Carthage, or where competition could not be eliminated, to regulate trade by state-sponsored agreements with its commercial rivals;

- (3) suppression of piracy, and promotion of Carthage's ability to freely navigate the seas.[121]

Both the Phoenicians and the Cathaginians were well known in antiquity for their secrecy in general, and especially pertaining to commercial contacts and trade routes.[122][123][124] Both cultures excelled in commercial dealings. Strabo (63BC-AD21) the Greek geographer wrote that before its fall (in 146 BC) Carthage enjoyed a population of 700,000, and directed an alliance of 300 cities.[125] The Greek historian Polybius (c.203–120) referred to Carthage as "the wealthiest city in the world".[126]

Constitution of State

The government of Carthage was undoubtedly patterned after the Phoenician model, especially that of the mother city Tyre, but Phoenician cities had kings and Carthage apparently did not.[127] An important office was called in Punic the Suffets (a Semitic word agnate with the Old Hebrew Shophet, usually translated as Judges as in the Book of Judges). Yet the Suffet at Carthage was more an executive leader, although he also served in a judicial role; birth and wealth were the initial qualifications.[128] It appears that the Suffet was elected by the citizens, and held office for a one-year term; probably there were two of them at a time—hence quite comparable to the Roman Consulship. A crucial difference was that the Suffet had no military power. Carthaginian generals marshalled mercenary armies and were separately elected. From about 550 to 450 the Magonid family monopolized the top military position; later the Barcid family acted similarly. Eventually it came to be that, after a war, the commanding general had to testify justifying his actions before a court of 104 judges.[129]

Aristotle (384–322) discusses Carthage in his work, Politica; he begins: "The Carthaginians are also considered to have an excellent form of government." He briefly describes the city as a "mixed constitution", a political arrangement with cohabiting elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, i.e., a king (Gk: basileus), a council of elders (Gk: gerusia), and the people (Gk: demos).[130] Later Polybius of Megalopolis (c.204–122, Greek) in his Istoria would describe the Roman Republic in more detail as a mixed constitution in which the Consuls were the monarchy, the Senate the aristocracy, and the Assemblies the democracy.[131]

Evidently Carthage also had an institution of elders who advised the Suffets, similar to a Greek gerusia or the Roman Senate. We do not have a Punic name for this body. At times its members would travel with an army general on campaign. Members also formed permanent committees. The institution had several hundred members drawn from the wealthiest class who held office for life. Vacancies were probably filled by recruitment from among the elite, i.e., by co-option. From among its members were selected the 104 Judges mentioned above. Later the 104 would come to evaluate not only army generals but other office holders as well. Aristotle regarded the 104 as most important; he compared it to the ephorate of Sparta with regard to control over security. In Hannibal's time, such a Judge held office for life. At some stage there also came to be independent self-perpetuating boards of five who filled vacancies and supervised (non-military) government administration.[132]

Popular assemblies also existed at Carthage. When deadlocked the Suffets and the quasi-senatorial institution of elders might request the assembly to vote; also, assembly votes were requested in very crucial matters in order to achieve political consensus and popular coherence. The assembly members had no legal wealth or birth qualification. How its members were selected is unknown, e.g., whether by festival group or urban ward or another method.[133][134][135]

The Greeks were favorably impressed by the constitution of Carthage; Aristotle had a separate study of it made which unfortunately is lost. In his Politica he states: "The government of Carthage is oligarchical, but they successfully escape the evils of oligarchy by enriching one portion of the people after another by sending them to their colonies." "[T]heir policy is to send some [poorer citizens] to their dependent towns, where they grow rich."[136][137] Yet Aristotle continues, "[I]f any misfortue occurred, and the bulk of the subjects revolted, there would be no way of restoring peace by legal means." Aristotle remarked also:

"Many of the Carthaginian institutions are excellent. The superiority of their constitution is proved by the fact that the common people remain loyal to the constitution; the Carthaginians have never had any rebellion worth speaking of, and have never been under the rule of a tyrant."[138]

Here one may remember that the city-state of Carthage, who citizens were mainly Libyphoenicians (of Phoenician ancestry born in Africa), dominated and exploited an agricultural countryside composed mainly of native Berber sharecroppers and farmworkers, whose affiliations to Carthage were open to divergent possibilities. Beyond these more settled Berbers and the Punic farming towns and rural manors, lived the independent Berber tribes, who were mostly pastoralists.[139]

In the brief, uneven review of government at Carthage found in his Politica Aristotle mentions several faults. Thus, "that the same person should hold many offices, which is a favorite practice among the Carthaginians." Aristotle disapproves, mentionting the flute-player and the shoemaker. Also, that "magistrates should be chosen not only for their merit but for their wealth." Aristotle's opinion is that focus on pursuit of wealth will lead to oligarchy and its evils.

"[S]urely it is a bad thing that the greatest offices... should be bought. The law which allows this abuse makes wealth of more account than virtue, and the whole state becomes avaricious. For, whenever the chiefs of the state deem anything honorable, the other citizens are sure to follow their example; and, where virtue has not the first place, their aristocracy cannot be firmly established."[140]

In Carthage the people seemed politically satisfied and submissive, according to the historian Warmington. They in their assemblies only rarely exercised the few opportunities given them to assent to state decisions. Popular influence over government appears not to have been an issue at Carthage. Being a commercial republic fielding a mercenary army, the people were not conscripted for military service, an experience which can foster the feel for popular political action. But perhaps this misunderstands the society; perhaps the people, whose values were based on small-group loyalty, felt themselves sufficiently connected to their city's leadership by the very integrity of the person-to-person linkage within their social fabric. Carthage was very stable; there were few openings for tyrants. Only after defeat by Rome devastated Punic imperial ambitions did the people of Carthage seem to question their governance and to show interest in political reform.[141]

In 196, following the Second Punic War (218–201), Hannibal Barca, still greatly admired as a Barcid military leader, was elected Suffet. When his reforms were blocked by a financial official about to become a Judge for life, Hannibal rallied the populace against the 104 Judges. He proposed a one-year term for the 104, as part of a major civic overhaul. Additionally, the reform included a restructuring of the city's revenues, and the fostering of trade and agriculture. The changes rather quickly resulted in a noticeable increase in prosperity. Yet his incorrigible political opponents cravenly went to Rome, to charge Hannibal with conspiracy, namely, plotting war against Rome in league with Antiochus the Hellenic ruler of Syria. Although the Roman Scipio Africanus resisted such maneuver, eventually intervention by Rome forced Hannibal to leave Carthage. Thus, corrupt city officials efficiently blocked Hannibal Barca in his efforts to reform the government of Carthage.[142][143]

The above discussion about the constitution basically follows the scholarship of Warmington. The sources for the early descriptions are largely by Greek foreigners, who likely would see in Carthage reflections of their own institutions. How strong was the Hellenizing influence within Carthage? The basic difficulty is the lack of adequate writings due not only to the secretive nature of the Punic state, but also to the utter destruction of the capital city and its records.[144] Another view of the constitution of Carthage is given by the historian Picard as follows.

Mago (6th century) was King of Carthage, Punic MLK or malik (Greek basileus), not merely a SFT or Suffet, which then was only a minor official. Mago as MLK was head of state and war leader; being MLK was also a religious office. His family was considered to possess a sacred quality. Mago's office was somewhat similar to that of Pharaoh, but although kept in a family it was not hereditary, it was limited by legal consent. Picard, accordingly, believes that the council of elders and the popular assembly are late institutions. Carthage was founded by the King (MLK) of Tyre who had a royal monopoly on this trading venture. Thus it was the royal authority stemming from this traditional source of power that the MLK of Carthage possessed. Later, as other Phoenician ship companies entered the trading region, and so associated with the city-state, the MLK of Carthage had to keep order among a rich variety of powerful merchants in their negotiations among themselves and over risky commerce across the Mediterranean. Under these circumstance, the office of MLK began to be transformed. Yet it was not until the aristocrats of Carthage became wealthy owners of agricultural lands in Africa that a council of elders was institutionalized at Carthage.[145]

Punic religion

The Phoenicians of Tyre brought their inherited customs and habitual understandings with them to north Africa. The religious practices and beliefs of Phoenicia were cognate generally to their neighbors in Canaan, which in turn shared characteristics common throughout the ancient Semitic world.[146][147][148] "Canaanite religion was more of a public institution than of an individual experience." Its rites were primarily for city-state purposes; payment of taxes by citizens was considered in the category of religious sacrifices.[149] Unfortunately, much of the Phoenician sacred writings known to the ancients have been lost.[150][151]

Like their Hebrew cousins the Phoenicians were known for being very religious. While there remain favorable aspects regarding Canaanite religion,[152][153][154] several of its reported practices have been widely criticized, in particular, temple prostitution,[155] and child sacrifice.[156] The tradition of temple prostitution became forbidden in Hebrew religion, e.g., by the reforms instituted under King Josiah.[157] In the foundation story of Abraham and Isaac,[158] it is shown that the ancient, regional, religious practice of child sacrifice was not required by the Hebrew Deity.[159][160] Notwithstanding these and other important differences, cultural religious similarities between the ancient Hebrews and the Phoenicians persisted.[152][161]

Canaanite religious mythology does not appear as elaborated compared with existent literature of their cousin Semites in Mesopotamia. In Canaan the supreme god was called El, which means "god" in common Semitic.[162][163] The storm god Baal, meaning "master".[164] Other gods were called by royal titles, as in Melqart meaning "king of the city",[165] or Adonis for "lord".[166] On the other hand the Phoenicians, notorious for being secretive in business, might use these non-descript words as cover for the secluded name of the god,[167] known only to a select few initiated into the inmost circle, or not even used by them, much as their neighbors the ancient Hebrews used the word Adonai (Heb: "Lord") to place a cover over the name of their God.[168]

The Semitic pantheon was well-populated; which god became primary evidently depended on the exigencies of a particular city-state or tribal locale.[169][170] Due perhaps to the leading role of the city-state of Tyre, its reigning god Melqart was prominent throughout Phoenicia and overseas. Also of great general interest was Astarte (Heb: Ashtoreth), (Bab: Ishtar), a fertility goddess who also enjoyed regal and matronly aspects. The prominent deity Eshmun of Sidon developed from a chthonic nature for agriculture into a god of health and healing. Associated with the fertility and harvest myth widespread in the region, in this regard Eshmun was linked with Astarte; other like pairings included Ishtar and Tammuz in Babylon, and Isis and Osiris in Egypt.[171]

Religious institutions of great antiquity in Tyre, called marzeh (MRZH, "place of reunion"), did much to foster social bonding and "kin" loyalty.[172] These institutions held banquets for their membership on festival days. Various marzeh societies developed into elite fraternities, becoming very influential in the commercial trade and governance of Tyre. As now understood, each marzeh originated in the congeniality inspired and then nurtured by a series of ritual meals, shared together as trusted "kin", all held in honor of the deified ancestors.[173] Later, at the Punic city-state of Carthage, the "citizen body was divided into groups which met at times for common feasts." Such festival groups may also have composed the voting cohort for selecting members of the city-state's Assembly.[174][175]

Religion in Carthage was based on inherited Phoenician ways of devotion. In fact, until its fall embassies from Carthage would regularly make the journey to Tyre to worship Melqart, bringing material offerings.[176][177] Transplanted to distant Carthage, these Phoenician ways persisted, but naturally acquired distinctive traits: perhaps influenced by a spiritual and cultural evolution, or synthesizing Berber tribal practices, or transforming under the stress of political and economic forces encountered by the city-state. Over time the original Phoenician exemplar developed distinctly, becoming the Punic religion at Carthage.[178] "The Carthaginians were notorious in antiquity for the intensity of their religious beliefs."[179] "Besides their reputation as merchants, the Carthaginians were known in the ancient world for their superstition and intense religiousity. They imagined themselves living in a world inhabited by supernatural powers which were mostly malevolent. For protection they carried amulets of various origins and had them buried with them when they died."[180]

At Carthage as at Tyre religion was integral to the city's life. A committee of ten elders selected by the civil authorities regulated worship and built the temples with public funds. Some priesthoods were hereditary to certain families. Punic inscriptions list a hierarchy of cohen (priest) and rab cohenim (lord priests). Each temple was under the supervision of its chief priest or priestess. To enter the Temple of Eshmun one had to abstain from sexual intercourse for three days, and from eating beans and pork.[181] Private citizens also nurtured their own destiny, as evidenced by the common use of theophoric personal names, e.g., Hasdrubal, "he who has Baal's help" and Hamilcar [Abdelmelqart], "pledged to the service of Melqart".[182]

The city's legendary foundress, Elissa or Dido, was the widow of Acharbas the high priest of Tyre in service to its principal deity Melqart.[183] Dido was also attached to the fertility goddess Astarte. With her Dido brought not only ritual implements for the worship of Astarte, but also her priests and sacred prostitutes (taken from Cyprus).[184] The agricultural turned healing god Eshmun was worshipped at Carthage, as were other dieities. Melqart became supplanted at the Punic city-state by the emergent god Baal Hammon, which perhaps means "lord of the altars of incense" (thought to be an epithet to cloak the god's real name).[185][186] Later, another newly arisen deity arose to eventually reign supreme at Carthage, a goddess of agriculture and generation who manifested a regal majesty, Tanit.[187]

The name Baal Hammon (BL HMN) has attracted scholarly interest. The more accepted etymology is to "heat" (Sem: HMN). Modern scholars at first associated Baal Hammon with the Egyptian god Ammon of Thebes, both the Punic and the Egyptian being gods of the sun. Both also had the ram as a symbol. The Egyptian Ammon was known to have spread by trade routes to Libyans in the vicinity of modern Tunisia, well before arrival of the Phoenicians. Yet Baal Hammon's derivation from Ammon no longer may considered the most likely, as Baal Hammon has since been traced also to Syrio-Phoenician origins, confirmed by recent finds at Tyre.[188] Baal Hammon is also presented as a god of agriculture: "Baal Hammon's power over the land and its fertility rendered him of great appeal to the inhabitants of Tunisia, a land of fertile wheat- and fruit-bearing plains."[189][190]

"In Semitic religion El, the father of the gods, had gradually been shorn of his power by his sons and relegated to a remote part of his heavenly home; in Carthage, on the other hand, he became, once more, the head of the pantheon, under the enigmatic title of Ba'al Hammon."[185]

Prayers of individual Carthaginians were often addressed to Baal Hammon. Yet this deity was recipient of the very troubling practice of child sacrifice.[191][192][193] Diodorus (late 1st century BCE) wrote that when Agathocles had attacked Carthage (in 310) several hundred children of leading families were sacrificed to regain the god's favor.[194] Modernly, the French novelist Gustave Flaubert's 1862 work Salammbô graphically featured this god as accepting such sacrifice.[195]

The goddess Tanit during the 5th and 4th centuries became queen goddess, supreme over the city-state of Carthage, thus outshining the former chief god and her associate, Baal Hammon.[197][198] Tanit was represented by "palm trees weighed down with dates, ripe pomegranates ready to burst, lotus or lilies coming into flower, fish, doves, frogs... ." She gave to mankind a flow of vital energies.[199][200] Tanit may be Berbero-Libyan in origin, or at least assimilated to a local deity.[201][202]Another view, supported by recent finds, holds that Tanit originated in Phoenicia, being closely linked there to the goddess Astarte.[203][204] Tanit and Astarte: each one was both a funerary and a fertility goddess. Each was a sea goddess. As Tanit was associated with Ba'al Hammon the principal god in Punic Carthage, so Astarte was with El in Phoenicia. Yet Tanit was clearly distinguished from Astarte. Astarte's heavenly emblem was the planet Venus, Tanit's the crescent moon. Tanit was portrayed as chaste; at Carthage religious prostitution was apparently not practiced.[205][206] Yet temple prostitution played an important role in Astarte's cult at Phoenicia. Also, the Greeks and Romans did not compare Tanit to the Greek Aphrodite nor to the Roman Venus as they would Astarte. Rather the comparison of Tanit would be to Hera and to Juno, regal goddesses of marriage, or to the goddess Artemis of child-birth and the hunt.[207] Tertullian (c.160 – c.220), the Christian theologian and native of Carthage, wrote comparing Tanit to Ceres, the Roman mother goddess of agriculture.[208]

Tanit has also been identified with three different Canaanite goddesses (all being sisters/wives of El): the above 'Astarte; the virgin war goddess 'Anat; and the mother goddess 'Elat or Asherah.[209][210][211] Her being a goddess, or symbolizing a psychic archetype, accordingly it is difficult to assign a single nature to Tanit, or to clearly represent her to consciousness.[212]

A problematic theory derived from sociology of religion proposes that as Carthage passed from being a Phoenician trading station into a wealthy and sovereign city-state, and from a monarchy anchored to Tyre into a native-born Libyphoenician oligarchy, Carthaginians began to turn away from deities associated with Phoenicia, and slowly to discover or synthesize a Punic deity, the goddess Tanit.[213] A parallel theory posits that when Carthage acquired as a source of wealth substantial agricultural lands in Africa, a local fertility goddess, Tanit, developed or evolved to eventually became supreme.[180] A basis for such theories may well be the religious reform movement that emerged and prevailed at Carthage during the years 397-360. The catalyst for such dramatic change in Punic religious practice was their recent defeat in war when led by their king Himilco (d. 396) against the Greeks of Sicily.[214]

Such transformation of religion would have been instigated by a faction of wealthy land owners at Carthage, including these reforms: overthrow of the monarchy; elevation of Tanit as queen goddess and decline of Baal Hammon; allowance of foreign cults of Greek origin into the city (Demeter and Kore); decline in child sacrifice, with most votive victims changed to small animals, and with the sacrifice not directed for state purposes but, when infrequently done, performed to solicit the deity for private, family favors. This bold historical interpretation understands the reformer's motivation as "the reaction of a wealthy and cultured upper class against the primitive and antiquated aspects of the Canaanite religion, and also a political move intended to break the power of a monarchy which ruled by divine authority." The reform's popularity was precarious at first. Later, when the city was in danger of immanent attack in 310, there would be a marked regression to child sacrifice. Yet eventually the cosmopolitan religious reform and the popular worship of Tanit together contributed to "breaking through the wall of isolation which had surrounded Carthage."[215][216][217]

"When the Romans conquered Africa, Carthaginian religion was deeply entrenched even in Libyan areas, and it retained a great deal of its character under different forms." Tanit became Juno Caelestis, "and Caelestis was supreme at Carthage itself until the triumph of Christianity, just as Tanit had been in pre-Roman times." [218] Regarding Berber (Libyan) religious beliefs, it has also been said:

"[Berber] belief in the powers of the spirits of the ancestors was not eclipsed by the introduction of new gods--Hammon, or Tanit--but existed in parallel with them. It is this same duality, or readiness to adopt new cultural forms while retaining the old on a more intimate level, which characterizes the [Roman era]."[219]

Such Berber ambivalence, the ability to entertain multiple mysteries concurrently, apparently characterized their religion during the Punic era also. After the passing of Punic power, the great Berber king Masinissa (r. 202–148), who long fought and challenged Carthage, was widely venerated by later generations of Berbers as divine.[220]

See also

- Phoenicia

- Phoenician languages

- Utica

- Carthage

- Hanno the Great

- Hannibal Barca

- Syphax

- Masinissa

- Scipio Africanus

- Jugurtha

- Juba I of Numidia

- Berber people

- Berber languages

- Ancient Libya

- North Africa during the Classical Period

- History of Tunisia

- Outlines of early Tunisia

- History of Punic-era Tunisia: chronology

- Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia

- History of Roman-era Tunisia

Reference notes

- ↑ References to sources are found in the notes to the text that follows.

- ↑ Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 40–41 (Greeks), .

- ↑ Cf., Warmington, Carthage (1960; Penguin 1964) at 24–25 (Greeks), 259–260 (Romans).

- ↑ B.H.Warmington, "The Carthiginian Period" at 246–260, 246 ("No Carthaginian literature has survived."), in General History of Africa, volume III. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990) Abridged Edition.

- ↑ R. Bosworth Smith, Carthage and the Carthaginians (London: Longmans, Green 1878, 1902) at 12. Smith's catalogue has not been appreciably augmented since, but for newly found inscriptions.

- ↑ Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 72-73: translation of Romano-Punic Treaty, 509 BC; at 72–78: discussion.

- ↑ Polybius (c. 200 – 118), Istorion at III, 22-25, selections translated as Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin 1979) at 199–203. Nota bene: Polybius died well over 70 years before the start of the Roman Empire.

- ↑ Cf., Arnold J. Toynbee, Hannibal's Legacy (1965) at I: 526, Appendix on the treaties.

- ↑ Hanno's log translated in full by Warmington, Carthage (1960) at 74–76.

- ↑ E.g., by Varro (116–27) in his De re rustica; by Columella (fl. AD 50–60) in his On trees and On agriculture, and by Pliny (23–79) in his Naturalis Historia. See below, paragraph on Mago's work.

- ↑ Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 122–123 (28 books), 140 (quotation of paragraph).

- ↑ Cf., H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Lanin Literature (London: Methuen 1930, 3d ed. 1954; reprint Dutton, New York 1960) at 51-52, where a plot summary of Poenulus (i.e., "The Man from Carthage") is given. Its main characters are Punic.

- ↑ Eighteen lines from Poenulus are spoken in Punic by the character Hanno in Act 5, scene 1, beginning "Hyth alonim vualonuth sicorathi si ma com sith... ." Plautus gives a Latin paraphrase in the next ten lines. The gist is a prayer seeking divine aid in his quest to find his lost kin. The Comedies of Plautus (London: G. Bell and Sons 1912), translated by Henry Thomas Riley. The scholar Bochart considered the first ten lines to be Punic, but the last eight to be 'Lybic'. Another scholar, Samuel Petit, translated the text as if it were Hebrew, a sister-language of Punic. This according to notes accompanying the above scene by H. T. Riley.

- ↑ Soren, Ben Khader, Slim, Carthage (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990) at 42 (over 6000 inscriptions found), at 139 (many very short, on religious stele).

- ↑ An example of a longer inscription (of about 279 Punic characters) exists at Thugga, Tunisia. It concerns the dedication of a temple to the late king Masinissa. A translated text appears in Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1997) at 39.

- ↑ Glenn E. Markoe, Carthage (2000) at 114.

- ↑ Picard and Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 30.

- ↑ Cf., Victor Matthews, "The libri punici of King Hiempsal" in American Journal of Philology 93: 330–335 (1972); and, Véronique Krings, "Les libri Punici de Sallust" in L'Africa Romana 7: 109–117 (1989). Cited by Roller (2003) at 27,n110.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (23–79), Naturalis Historia at XVIII, 22–23.

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 358-360. Lancel here remarks that, following the fall of Carthage, there arose among the Romans there a popular reaction against the late Cato the Elder (234–149), the Roman censor who had notoriously lobbied for the destruction of the city. Lancel (1995) at 410.

- ↑ Ronald Syme, however, in his Sallust (University of California, 1964, 2002) at 152–153, discounts any unique value of the libri punici mentioned in his Bellum Iugurthinum.

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 359, raises questions concerning the provenance of these books.

- ↑ Hiempsal II was the great-grandson of Masinissa (r. 202–148), through Mastanabal (r. 148–140) and Gauda (r. 105–88). D. W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (2003) at 265.

- ↑ Sallust, Bellum Iugurthinum (ca. 42) at ¶17, translated as The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1963) at 54.

- ↑ R. Bosworth Smith, in his Carthage and the Carthaginians (London: Longmans, Green 1878, 1908) at 38, laments that Sallust declined to directly address the history of the city of Carthage.

- ↑ Duane W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene. Royal scholarship on Rome's African frontier (New York: Routledge 2003), at 183, 191, in his Chapter 8: "Libyka" (183–211) [cf., 179]; also at 19, 27, 159 (Juba's library described), 177 (per his book on Hanno).

- ↑ Juba II's literary works are reviewed by D. W. Roller in The World of Jube II and Kleopatra Selene (2003) at chapters 7, 8, and 10.

- ↑ Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker (Leiden 1923-), ed. Felix Jacoby, re "Juba II" at no. 275 (per Roller (2003) at xiii, 313).

- ↑ Duane W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (2003) at 189,n22; cf., 177.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (23–79), Naturalis Historia V, 8; II, 169.

- ↑ Cf., Picard and Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (Paris: Hachette [1968]; New York: Taplinger 1969) at 93–98, 115–119.

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage. A History (Paris 1992; Oxford 1995) at 358–360.

- ↑ See section herein on Berber relations. See Early History of Tunisia for both indigenous and foreign reports concerning the Berbers, both in pre-Punic and Punic times.

- ↑ Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (London: British Museum, Berkely: University of California 2000) at 21–22 (affinity), 95–96 (economy), 115–119 (religion), 137 (funerals), 143 (art).

- ↑ David Diringer, Writing (London: Thames and Hudson 1962) at 115–116. The Ugarit tablet were discovered in 1929.

- ↑ Allen C. Myers, editor, The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids: 1987) at 1027–1028.

- ↑ Markoe, Phoenicians (2000) at 119. Eusebius of Caesarea (263–339), the Church Historian, quotes the Greek of Philo of Byblos whose source was the Phoenician writings of Sanchuniathon. Some doubt the existence of Sanchuniathon.

- ↑ Cf., Attridge & Oden, Philo of Byblos (1981); Baumgarten, Phoenician History of Philo of Byblos (1981). Cited by Markoe (2000).

- ↑ Donald Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 83–84.

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati, Il Mondo dei Fenici (1966), translated as The World of the Phoenicians (London: Cardinal 1973) at 55. Prof. Moscati offers the tablets found at ancient Ugarit as independent substantiation for what we know about Sanchuniathon's writings.

- ↑ Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 128–129.

- ↑ The ancient Romanized Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37–100s) also mentions a lost Phoenician work; he quotes from a Phoenician History of one "Dius". Josephus, Against Apion (c.100) at I:17; found in The Works of Josephus translated by Whiston (London 1736; reprinted by Hendrickson, Peabody, Massachusetts 1987) at 773–814, 780.

- ↑ Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (Univ.of California 2002) at 11, 110. Of course, this also applies to Carthage. Cf., Markoe (2000) at 114.

- ↑ Strabo (c. 63 B.C. – A.D. 20s), Geographia at III, 5.11.

- ↑ "He knows all lingos, but pretends he doesn't. He must be Punic; need we labor it?" From Poenulus at 112–113, by the Roman playwright Plautus (c. 250–184). Cited by Hardon, The Phoenicians (1963) at 228, n102.

- ↑ Markoe, Phoenicians (2000) at 110, at 11. Inserted in second Markoe quote: [language].

- ↑ Cf., Harden, The Phoenicians (1963) at 123. [Ancient Peoples and Places]

- ↑ Soren, Ben Khader, Slim, 'Carthage (New York: Simon and Schuster 1990) at 34–35 (script), at 42 (inserted in quote: [the alphabet]).

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer, A History of Writing (London: Reaktion 2001) at 82–93. Facsimiles of early alphabetical writing from ancient inscriptions are given for: Proto-Canaanite in the Levant of the 2nd millennium (at 88), Phoenician (Old Hebrew) in Moab of 842 (at 91), Phoenician (Punic) in Marseilles [France] circa 300 BC (at 92). Also given (at 92) is a bilingual (Punic and Numidian) inscription from Thugga [Tunisia] circa 218–201, which regards a temple being dedicated to king Masinissa.

- ↑ David Diringer, Writing (London: Thames and Hudson 1962) at 112–121.

- ↑ See section "Founding of the City" in History of Punic-era Tunisia.

- ↑ Cf., the lengthy discussion in Stéphanie Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord, volume four (Paris 1920).

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage. A History (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 273–274 (Mago quoted by Columella), 278–279 (Mago and Cato's book), 358 (translations).

- ↑ Pliny the Elder praises Mago's agricultural works in his Naturalis Historia XVIII,5.

- ↑ The pomegranate was called the "Punic apple" by the Romans: malum Punicum. Lancel Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 277.

- ↑ Gilbert and Colette Charles-Picard, La vie quotidienne à Carthage au temps d'Hannibal (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1958), translated as Daily Life in Carthage (London: George Allen & Unwin 1961; reprint Macmillan, New York 1968) at 83–93: 88 (Mago as retired general), 89–91 (fruit trees), 90 (grafting), 89–90 (vineyards), 91–93 (livestock and bees), 148–149 (wine making). Elephants also, of course, were captured and reared for war (at 92).

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati, Il mondo dei Fenici (1966), translated as The World of the Phoenicians (London: Cardinal 1973) at 219–223. Hamilcar is named as another Carthaginian writing on agriculture (at 219).

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995), discussion of wine making and its 'marketing' at 273–276. Lancel says (at 274) that about wine making, Mago was silent. Punic agriculture and rural life are addressed at 269–302.

- ↑ G. and C. Charles-Picard, La vie quotidienne à Carthage au temps d'Hannibal (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1958) translated as Daily Life in Carthage (London: George Allen and Unwin 1961; reprint Macmillan 1968) at 83–93: 86 (quote); 86–87, 88, 93 (management); 88 (overseers).

- ↑ G. C. and C. Picard, Vie et mort de Carthage (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1970) translated (and first published) as The Life and Death of Carthage (New York: Taplinger 1968) at 86 and 129.

- ↑ Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 83–84: the development of a "landed nobility".

- ↑ B. H. Warmington, in his Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 155.

- ↑ Mago, quoted by Columella at I,i,18; in Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 87, 101,n37.

- ↑ Mago, quoted by Columella at I,i,18; in Moscati, The World of the Phoenicians (1966; 1973) at 220, 230,n5.

- ↑ See section "Berber relations" in History of Punic-era Tunisia.

- ↑ Gilbert and Colette Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 83–85 (invaders), 86–88 (rural proletariat).

- ↑ E.g., Gilbert Charles Picard and Colette Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (Paris 1970; New York 1968) at 168–171, 172–173 (invasion of Agathocles in 310 BC). The mercenary revolt (240–237) following the First Punic War was also largely and actively, though unsuccessfully, supported by rural Berbers. Picard (1970; 1968) at 203–209.

- ↑ Plato (c. 427 – c. 347) in his Laws at 674, a-b, mentions regulations at Carthage restricting the consumption of wine in specified circumstances. Cf., Lancel, Carthage (1997) at 276.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960, 2d ed. 1969) at 136–137.

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992) translated by Antonia Nevill (Oxford: Blackwell 1997) at 269–279: 274–277 (produce), 275–276 (amphora), 269–270 & 405 (Rome), 269–270 (yields), 270 & 277 (lands), 271–272 (towns).

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Bibleoteca, at XX, 8, 1–4, transl. as Library of History (Harvard University 1962), vol.10 [Loeb Classics, no.390); per Soren, Khader, Slim,, Carthage (1990) at 88.

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 277.

- ↑ Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 85 (limited area), at 88 (imported skills).

- ↑ e.g., the Greek writers: Appian, Diodorus Siculus, Polybius; and, the Latin: Livy, Strabo.

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992), as translated by A. Nevill (Oxford 1997), at 38–45 and 76–77 (archaic Carthage): maps of early city at 39 and 42; burial archaeology quote at 77; short quotes at 43, 38, 45, 39; clay masks at 60-62 (photographs); terracotta and ivory figurines at 64–66, 72–75 (photographs). Ancient coastline from Utica to Cartage: map at 18.

- ↑ Cf., B. H. Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; 2d ed. 1969) at 26–31.

- ↑ Virgil (70-19 BC), The Aeneid [19 BC], translated by Robert Fitzgerald [(New York: Random House 1983), at 18–19 (Book I, 576–586), or I, 421–424 (these two distinct line notations are unexplained). Cf., Lancel, Carthage (1997) at 38. Here capitalized as prose.

- ↑ Virgil here, however, does innocently inject his own Roman cultural notions into his imagined description, e.g., Punic Carthage evidently built no theaters per se. Cf., Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968).

- ↑ City maps in Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997), at 39, 42, 138, 145, 416.

- ↑ The harbors, often mentioned by ancient authors, remain an archeological problem due to the limited, fragmented evidence found. Lancel, Carthage (1992; 1997) at 172–192 (the two harbors).

- ↑ Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 32, 130–131.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 138.

- ↑ Sebkrit er Riana to the north, and El Bahira to the south [their modern names]. Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 31-32. Ships then could also be beached on the sand.

- ↑ Cf., Lancel, Carthage (1992; 1997) at 139-140, city map at 138.

- ↑ The lands immediately south of the hill is often also included by the term Byrsa.

- ↑ Serge Lancel, Carthage. A history (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 148–152; 151 and 149 map (leveling operations on the Byrsa, circa 25 BC, to prepare for new construction), 426 (Temple of Eshmun), 443 (Byrsa diagram, circa 1859). The Byrsa had been destroyed during the Third Punic War (149–146).

- ↑ Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (Paris 1958; London 1961, reprint Macmillan 1968) at 8 (city map showing the Temple of Eshmoun, on the eastern heights of the Byrsa).

- ↑ E. S. Bouchier, Life and Letters in Roman Africa (Oxford: B. H. Blackwell 1913) at 17, and 75. The Roman temple to Juno Caelestis is said to be later erected on the site of the ruined temple to Tanit.

- ↑ On the Byrsa some evidence remains of quality residential construction of 2nd century BC. Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 117.

- ↑ B. H. Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 15 (quote), 25, 141; (London: Robert Hale, 2d ed. 1969) at 27 (quote), 131–132, 133 (enclosure).

- ↑ See the section on Punic religion below.

- ↑ Cf., Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 141.

- ↑ Modern archeologists on the site have not yet 'discovered' the ancient agora. Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 141.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 142.

- ↑ Appian of Alexandria (c.95 – c.160s), Pomaika known as the Roman History, at VII (Libyca), 128.

- ↑ Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 133 & 229n17 (Appian cited).

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 152–172, e.g., 163–165 (floorplans), 167–171 (neighborhood diagrams and photographs).

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 139 (map of city, re the tophet), 141.

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 138–140. These findings mostly relate to the 3rd century BC.

- ↑ Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (Paris 1970; New York 1968) at 162–165 (carvings described), 176–178 (quote).

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (1992; 1997) at 138 and 145 (city maps).

- ↑ This was especially so, later in the Roman era. E.g., Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 187–210.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1964) at 138–140, map at 139; at 273n.3, he cites the ancients: Appian, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, Polybius.

- ↑ Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963), text at 34, maps at 31 and 34. According to Harden, the outer walls ran several kilometers to the west of that indicated on the map here.

- ↑ Picard and Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 395–396.

- ↑ For an ample discussion of the ancient city: Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995, 1997) at 134–172, ancient harbors at 172–192; archaic Carthage at 38-77.

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati, Il mundo de Fenici (1966); translated as The World of the Phoenicians (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson 1968; reprinted by Cardinal, London 1973) at 113–114.

- ↑ Baramki, Phoenicia and the Phoenicians (Bierut: Khayats 1961) at 62–64, 64–67 (jewelry), 69–75 (glass), 63, 75–77 (ceramics).

- ↑ See above section, "City and country" section.

- ↑ Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 158.

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; London 1995) at 100–101.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (London 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 73–74.

- ↑ Herodotus, Istorion, IV, [196], translated as The Histories (Penguin 1954, rev'd ed. 1972) at 336.

- ↑ Cf., Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (Paris 195; Oxford 1961, reprint Macmillan 1968) at 165, 171–177.

- ↑ Donald Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 57–62 (Cyprus and Aegean), 62–65 (western Mediterranean); 157–170 (trade); 67–70, 84–85, 160–164 (the Greeks).

- ↑ Strabo, Geographica, XVII,3,15; as translated by H. L. Jones (Loeb Classic Library 1932) at VIII: 385.

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati, The World of the Phoenicians (1966; 1973) at 223–224.

- ↑ Richard J. Harrison, Spain at the Dawn of History (London: Thames and Hudson 1988), "Phoenician colonies in Spain" at 41–50, 42.

- ↑ Cf., Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 157–166.

- ↑ E.g., during the reign of Hiram (tenth century) of Tyre. Sabatino Moscati, Il Mondo dei Fenici (1966), translated as The World of the Phoenicians (1968, 1973) at 31–34.

- ↑ Stéphane Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1924) at volume IV: 113.

- ↑ Strabo (c.63 B.C. – A.D. 20s), Geographia at III, 5.11.

- ↑ Walter W. Hyde, Ancient Greek Mariners (Oxford Univ. 1947) at 45–46.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 81 (secretive), 87 (monopolizing).

- ↑ Strabo, Geographica, XVII,3,15; in the Loeb Classic Library edition of 1932, translated by H. L. Jones, at VIII: 385.

- ↑ Cf., Theodor Mommsen, Römische Geschicht (Leipzig: Reimer and Hirzel 1854–1856), translated as the History of Rome (London 1862-1866; reprinted by J. M. Dent 1911) at II: 17–18 (Mommsen's Book III, Chapter I).

- ↑ This discussion first follows Warmington in essence, then turns to Picard's substantially different results.

- ↑ A circa 2nd century BC bilingual inscription from Thugga (modern Dougga, Tunisia), describes Berber political office holders, one of the offices being the Suffet (SFT], which indicates influence by Carthage on Berber state institutions. Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996) at 39.

- ↑ Warmington, B. H. (1960, 1964). Carthage. Robert Hale, Pelican. pp. 144–147. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Aristotle, Politica at Book II, Chapter 11, (1272b–1274b); in The Basic Works of Aristotle edited by R. McKeon, translated by B. Jowett (Random House 1941), Politica at pages 1113–1316, "Carthage" at 1171–1174.

- ↑ Polybius, Histories VI, 11–18, translated as The Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin 1979) at 311–318.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960; Penguin 1964) at 147–148.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960; Penguin 1964) at 148.

- ↑ Aristotle presents a slightly more expansive interpretation of the role of assemblies. Politica II, 11, (1273a/6–11); McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1172.

- ↑ Compare Roman assemblies.

- ↑ Aristotle, Politica at II, 11, (1273b/17–20), and at VI, 5, (1320b/4–6) re colonies; in McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1173, and at 1272.

- ↑ "Aristotle said that the oligarchy was careful to treat the masses liberally and allow them a share in the profitable exploitation of the subject territories." Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 149, citing Aristotle's Politica as here.

- ↑ Aristotle, Politica at II, 11, (1273b/23–24) re misfortune and revolt, (1272b/29–32) re constitution and loyalty; in McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1173, 1171.

- ↑ Refer to History of Punic-era Tunisia: chronology.

- ↑ Aristotle, Politica at II, 11, (1273b/8–16) re one person many offices, and (1273a/22–1273b/7) re oligarchy; in McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1173, 1172–1273.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 143–144, 148–150. "The fact is that compared to Greeks and Romans the Carthaginians were essentially non-political." Ibid. at 149.

- ↑ H. H. Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753–146 BC (London: Methuen 1935, 4th ed. 1980; reprint Routledge 1991) at 306–307.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage at 240–241, citing the Roman historian Livy.

- ↑ See above: Extant writings.

- ↑ Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968) at 80–86

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati, Ancient Semitic Civilizations (London 1957), e.g., at 40 & 113.

- ↑ W. Robertson Smith, Lectures on the Religion of the Semites (Edinburgh: A. & C. Black 1889; 2d ed. 1894; 3d ed. 1927); reprint by Meridian Library, New York, 1956, at 1–15.

- ↑ Cf. Julian Baldick, who posits an even greater and more ancient sweep of a common religious culture in his Black God. Afroasiatic roots of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim religions (London: Tauris 1998).

- ↑ Theodor H. Gaster, "The Religion of the Canaanites" at 113–143, 114–115, in Ancient Religions (New York: Philosophical Library 1950; reprint by Citadel Press, New York 1965), edited by Vergilius Ferm.

- ↑ Donald Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Frederick A. Praeger 1962) at 83–84.

- ↑ Much of what is now known about Canaanite religion comes from one source: cuneiform tablets found in 1928 at temple ruins of Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit). Gaster, "The Religion of the Canaanites" at 113–143, 114–115, in Ancient Religions (1950, 1965), ed. by Ferm.

- ↑ 152.0 152.1 S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "Canaanite Religion" at 173.

- ↑ Dmitri Baramki, Phoenicia and the Phoenicians (Beirut: Khayats 1961) at 55–58.

- ↑ Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (Univ.of California 2000) at 115–142.

- ↑ S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "Sacred Prostitution" at 512–513.

- ↑ S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "Molech" at 448.

- ↑ 2nd Kings 23:7. Cf., Deuteronomy 23:17.

- ↑ In Islam, Ishmael not Isaac is almost sacrificed by Abraham.

- ↑ Genesis 22:1–19. Also, Leviticus 18:21, & 20:2–5, forbidding the giving of "children to devote them by fire to Moloch." Contrast: Exodus 13:2, & 23:29, where the Deity commands: "The first born of your sons you shall give to me."

- ↑ "Tophets" built "to burn their sons and their daughters in the fire" are condemned by the Hebrew Deity in Jeremiah 7:30-32, and in 2nd Kings 23:10 (also 17:17).

- ↑ E.g., like the early Hebrews, in Carthage little importance was attached to the idea of life after death. Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 162.

- ↑ Cf., S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "El" at 258.

- ↑ Cf., Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Harvard Univ. 1973) at 10–75, i.e., "'El and the God of the Fathers" (13–43), "Yahweh and 'El" (44–75); and 177–186, i.e., "'El's modes of revelation" in "Yahweh and Ba'l" (147–194).

- ↑ Here, Baal was used instead of the storm god's name Hadad. S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "Hadad" at 315, "Adad" (Mesopotamia) at 28, ""Baal" at 124.

- ↑ Moscati, Ancient Semitic Civilizations at 113–114.

- ↑ S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "Adonis" at 29–30.

- ↑ B.H.Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 156: as an epithet to hide a god's real name.

- ↑ S.G.F.Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion (Scribners 1970), "YHVH" at 655; "Canaanite Religion" at 173.

- ↑ In Phoenicia and Canaan: the rejuvenating Melqart was the chief god of Tyre, Eshmun the god of healing at Sidon, Dagon (his son was Baal) at Ashdod, Terah the moon god of the Zebulun. In Mesopotamia: the moon god at Ur was called Sin (Sum: Nanna), the sun god Shamash at Larsa, the fertility goddess of Uruk being Ishtar, and the great god of Babylon being Marduk. Brandon (ed.), Dictionary of Comparative Religion re "Canaanite Religion" at 173, and "Phoenician Religion" at 501.

- ↑ Richard Carlyon, A Guide to the Gods (New York 1981) at 311, 315, 320, 324, 326, 329, 332, 333.

- ↑ Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962) at 85–86, 86, 87–88.

- ↑ Kinship status was not infrequently granted to genetically unrelated persons. Cf., Meyer Fortes, Kinship and the Social Order. The Legacy of Lewis Henry Morgan (Chicago: Aldine 1969) at 256.

- ↑ Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (Univ.of California 2000) at 120 (MRZH, marzeh).

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 148.

- ↑ Cf., William Robertson Smith, Lectures on The Religion of the Semites. Second and Third Series. {1890-1891} (Sheffield Academic Press 1995), "Feasts" at 33–43.

- ↑ Serge Lance, Carthage (Paris: Librairie Artheme Fayard 1992), translated as Carthage. A History (Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 193.

- ↑ Similarly, diaspora Jews also sent material support for the second Temple in Jerusalem until its fall in 70 CE. Cf., Allen C. Myers, editor, The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans 1987), "Temple" at 989–992, 991.

- ↑ Gilbert Charles Picard and Colette Picard, Vie et mort de Carthage (Paris: Hatchette 1968) translated as The Life and Death of Carthage (New York: Taplinger 1968) at 45.

- ↑ B.H.Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 155.

- ↑ 180.0 180.1 Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (1971) at 22.

- ↑ Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 161 (ten elders, priesthood, Temple of Eshmun).

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 193-194.

- ↑ Markoe, Phoenicians (Univ.of California 2000) at 129–130.

- ↑ Warmington (1960, 1964) at 157.

- ↑ 185.0 185.1 Picard and Picard, "The Life and Death of Carthage (1969) at 45.

- ↑ B. H. Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; Penguin 1964) at 155–158. Warmington associates Melqart with the pan-Semitic father god El. Regarding Baal Hammon, "the epithet [was] being used to avoid naming the name of the god." Warmington (1960, 1964) at 156.

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 199–204.

- ↑ Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992), translated as Carthage. A History (1995) at 195, 196. Lancel entertains other etymologies for BL HMN. If instead of HMN, one reads HM-N it would signify "protector". One author finds his origin in the name of a mountain to the north of Phoenicia, Amanus. Or the name may signify a small chapel, related to continuity, hence safety. Lancel (1992, 1995) at 194–199.

- ↑ Markoe, Phoenicians (University of California 2000) at 130. Markoe understands Baal Hammon as similar to Dagon, i.e., an agricultural god.

- ↑ Cf., Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Frederick A. Praeger 1962) at Plate 41, "Stele of Baal enthroned from Hadrumetum" (Sousse, Tunisia). Said by Markoe Phoenicians (2000) to represent Baal Hammon.