History of Guernsey

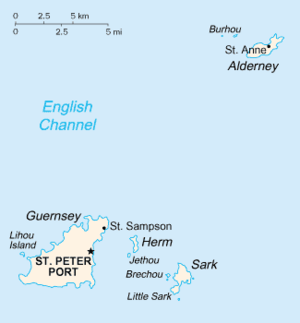

The history of Guernsey stretches back to evidence of prehistoric habitation and settlement and encompasses the development of its modern society.

Prehistory

Around 6000 B.C., rising sea created the English Channel and separated the Norman promontories that became the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey from continental Europe.[1] Neolithic farmers then settled on its coast and built the dolmens and menhirs found on the islands today. The island of Guernsey contains two sculpted menhirs of great archaeological interest, while the dolmen known as L'Autel du Dehus contains a dolmen deity known as Le Gardien du Tombeau.[2]

The arrival of Christianity

During their migration to Brittany, Britons occupied the Lenur islands (the former name of the Channel Islands[3]) including Sarnia or Lisia (Guernsey) and Angia (Jersey). It was formerly thought that the island's original name was Sarnia, but recent research indicates that this might have been the Latin name for Sark. (Sarnia nonetheless remains the island's traditional designation.) Travelling from the Kingdom of Gwent, Saint Sampson, later the abbot of Dol in Brittany, is credited with the introduction of Christianity to Guernsey.[4]

A chapel, dedicated to St Magloire, stood in the Vale. St Magloire was a nephew of St Samson of Dol, and was born about the year 535. The chapel in his name was mentioned in a bull of Pope Adrian IV as being in the patronage of Mont Saint-Michel, in Normandy; all traces of the chapel have gone. While the chapel would probably be of a much later date, St Magloire, the British missionary, may well have set up a centre of Christian worship before A.D. 600.

Somewhere around A.D. 968, monks, from the Benedictine monastery of Mont Saint-Michel, came to Guernsey to establish a community in the North of the Island. The Priory of Mont Saint-Michel was a dependency of the famous Abbey of Mont Saint-Michel.

The Duchy of Normandy

In 933 the islands, formerly under the control of William I, then Duchy of Brittany were annexed by the Duchy of Normandy. The island of Guernsey and the other Channel Islands represent the last remnants of the medieval Duchy of Normandy.[4] In the islands, Elizabeth II's traditional title as head of state is Duke of Normandy.[5] (The masculine nomenclature "Duke" is retained even when the monarch is female.)

According to tradition, Robert II, Duke of Normandy (the father of William the Conqueror) was journeying to England in 1032, to help Edward the Confessor. He was obliged to take shelter in Guernsey and gave land, now known as the Clos du Valle, to the monks. Furthermore, in 1061, when pirates attacked and pillaged the Island, a complaint was made to Duke William. He sent over Sampson D'Anneville, who succeeded, with the aid of the monks, in driving the pirates out. For this service, Sampson D' Anneville and the monks were rewarded with a grant of half the Island between them. The portion going to the monastery being known as Le Fief St Michel, and included the parishes of St Saviour, St Pierre du Bois, Ste. Marie du Catel, and the Vale.

During the Middle Ages, the island was repeatedly attacked by continental pirates and naval forces. This intensified during the Hundred Years War, when, starting in 1339, the island was occupied by the Capetians on several occasions.[4]

In 1372, the island was invaded by Aragonese mercenaries under the command of Owain Lawgoch (remembered as Yvon de Galles), who was in the pay of the French king. Lawgoch and his dark-haired mercenaries were later absorbed into Guernsey legend as an invasion by fairies from across the sea.[6]

The Reformation

.jpg)

In the mid-16th century, the island was influenced by Calvinist reformers from Normandy. During the Marian persecutions, three local women, the Guernsey Martyrs, were burned at the stake for their Protestant beliefs.[7]

Civil War

During the English Civil War, Guernsey sided with the Parliamentarians, while Jersey remained Royalist. Guernsey's decision was mainly related to the higher proportion of Calvinists and other Reformed churches, as well as Charles I's refusal to take up the case of some Guernsey seamen who had been captured by the Barbary corsairs. The allegiance was not total, however; there were a few Royalist uprisings in the southwest of the island, while Castle Cornet was occupied by the Governor, Sir Peter Osborne, and Royalist troops. Castle Cornet, which had been built to protect Guernsey, was turned on by the town of St. Peter Port, who constantly bombarded it. It was the last Royalist stronghold to capitulate (in 1651)[8] and was also the focus of a failed invasion attempt by Louis XIV of France in 1704.

Trade and emigration

Wars against France and Spain during the 17th and 18th centuries gave Guernsey shipowners and sea captains the opportunity to exploit the island's proximity to mainland Europe by applying for Letters of Marque and turning their merchantmen into privateers.

By the beginning of the 18th century, Guernsey's residents were starting to settle in North America.[9] The 19th century saw a dramatic increase in prosperity of the island, due to its success in the global maritime trade, and the rise of the stone industry. One notable Guernseyman, William Le Lacheur, established the Costa Rican coffee trade with Europe and the Corbet Family who created the Fruit Export Company[10]

Fort George was a former garrison for the British Army. Construction started in 1780, and was completed in 1812. It was built to accommodate the increase in the number of troops stationed in the island in anticipation of a French invasion during the Napoleonic Wars.

Le Braye du Valle was a tidal channel that made the northern extremity of Guernsey, Le Clos du Valle, a tidal island. Le Braye du Valle was drained and reclaimed in 1806 by the British Government as a defence measure. The eastern end of the former channel became the town and harbour (from 1820) of St. Sampson's, now the second biggest port in Guernsey. The western end of La Braye is now Le Grand Havre. The roadway called The Bridge across the end of the harbour at St. Sampson's recalls the bridge that formerly linked the two parts of Guernsey at high tide.

World War I

During World War I, approximately 3,000 island men served in the British Expeditionary Force. Of these, about 1,000 served in the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry regiment formed from the Royal Guernsey Militia in 1916.[11]

World War II

For most of World War II, the Bailiwick was occupied by German troops. Before the occupation, many Guernsey children had been evacuated to England to live with relatives or strangers during the war. Some children were never reunited with their families.[12]

The occupying German forces deported some of the Bailiwick's residents to camps in the southwest of Germany, notably to the Lager Lindele (Lindele Camp) near Biberach an der Riß. Among those deported was Ambrose (later Sir Ambrose) Sherwill, who, as the President of the States Controlling Committee, was de facto head of the civilian population. Sir Ambrose, who was Guernsey-born, had served in the British Army during the First World War and later became Bailiff of Guernsey. Three islanders of Jewish descent were deported to Auschwitz, never to return.[13] In Alderney, a concentration camp was built to house forced labourers, mostly from Eastern Europe. It was the only concentration camp built on British soil and is commemorated on memorials under Alderney's French name Aurigny.

Certain laws were passed at the insistence of the occupying forces. A reward, for example, was offered to informants who reported anyone for painting "V-for Victory" signs on walls and buildings, a practice that had become popular among islanders wishing to express their loyalty to Britain.

Guernsey was very heavily fortified during World War II out of all proportion to the island's strategic value, including by four 1911-vintage Russian 305 mm guns.[14] German defences and alterations remain visible, including additions made to Castle Cornet and a windmill. Hitler had become obsessed with the idea that the Allies would try to regain the islands at any price, so over 20% of the materials used to construct the "Atlantic Wall" (the Nazi attempt to defend continental Europe from seaborne invasion) was committed to the Channel Islands, including 47,000 sq m of concrete used for gun bases.[14] Most of the German fortifications remain intact and although the majority of them stand on private property, several are open to the public.[15][16]

Further Reading

Johnston, Peter, A Short History of Guernsey, 6th edition, Guernsey Society, (2014) ISBN 9780992886004

References

- ↑ "La Cotte Cave, St Brelade". Société Jersiaise. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ Evendon, J (11 February 2001). "Le Dehus – Burial Chamber (Dolmen)". The Megalithic Portal.

- ↑ "Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK". BBC. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Marr, J., The History of Guernsey – the Bailiwick's story, Guernsey Press (2001).

- ↑ "Channel Islands". The Royal Household Royal.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ de Garis, Marie (1986). Folklore of Guernsey. OCLC 19840362.

- ↑ Darryl Mark Ogier, Reformation And Society In Guernsey, Boydell Press, 1997, p.62.

- ↑ Portrait of the Channel Islands, Lemprière, London 1970 ISBN 0-7091-1541-5

- ↑ Guernsey's emigrant children. BBC – Legacies.

- ↑ Sharp, Eric (1976). "A very distinguished Guernseyman – Capt William le Lacheur, his ships and his impact on the early development, both economic and spiritual of Costa Rica". Transactions of La Société Guernesiaise (Guernsey) XX (1): 127ff.

- ↑ Parks, Edwin (1992). Diex Aix: God Help Us – The Guernseymen who marched away 1914–1918. Guernsey: States of Guernsey. ISBN 1-871560-85-3.

- ↑ "Evacuees from Guernsey recall life in Scotland". BBC News. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ↑ Janie Corbet I escaped the Nazi Holocaust, 9 July 2005, www.thisisguernsey.com.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Русские пушки на службе германского вермахта". NVO.ng.ru. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Channel Islands Occupation Society (Jersey)". CIOS Jersey. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ "Fortifications". CIOS Guernsey. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||