History and traditions of Harvard commencements

What was originally called Harvard Colledge (around which Harvard University eventually grew) held its first Commencement in September 1642, when nine degrees were conferred.[1] Today some 1700 undergraduate degrees, and 5000 advanced degrees from the university's various graduate and professional schools, are conferred each Commencement Day.

Each degree candidate attends three ceremonies: the Morning Exercises, at which degrees are conferred verbally en masse; a smaller midday ceremony (at the candidate's professional or graduate school, or upperclass House) in which actual diplomas are given in hand; and in the afternoon the annual meeting of the Harvard Alumni Association's, at which Harvard's President and the day's featured speaker deliver their addresses.[2]

Several hundred Harvard honorary degrees (which with few exceptions must be accepted in person) have been awarded since the first was bestowed on Benjamin Franklin in 1753.[3] In 1935 playwright George Bernard Shaw declined nomination for a Harvard honorary degree, suggesting instead that Harvard celebrate its three-hundredth anniversary by "burning itself to the ground ... as an example to all the other famous old corrupters of youth" such as Yale.

The ceremonies shifted from late summer to late June in the nineteenth century,[upper-alpha 1] and a number of unusual traditions have attached to them over the centuries, including the arrival of certain dignitaries on horseback, occupancy by Harvard's president of the Holyoke Chair (an awkward sixteenth-century contraption prone to tipping over) and the welcoming of newly minted bachelors to "the fellowship of educated men and women."

Daybreak rituals

Most upperclass Houses have rituals of their own. At Lowell House, for example, a perambulating bagpiper alerts seniors at 6:15 am for a 6:30 breakfast in the House dining hall with members of the Senior Common Room, after which all process (along with members of Eliot House, who have been similarly roused) to Memorial Church for a chapel service at 7:45.[6][7]

Morning Exercises

Morning Exercises are held in the central green of Harvard Yard (known as Tercentenary Theatre),[2] the dais at the steps of Memorial Church, facing Widener Library.[upper-alpha 2] Some 32,000 people attend the event, including university officials, civic dignitaries, faculty, honorees, alumni, family and guests. Degree candidates wear cap and gown or other academic regalia (see Academic regalia of Harvard University).[9]

Academic Parade

The first to enter are candidates for graduate and professional degrees, followed by alumni and alumnae. Candidates for undergraduate degrees enter next, traditionally removing headgear as they pass the John Harvard statue en route.[10][11] Finally comes the President's Procession, as follows:[1][12]

|

|

Holyoke Chair

At Cambridge. Is kept in the College there.

Seems but little the worse for wear.

That's remarkable when I say

It was old in President Holyoke's day.

On the dais the President occupies the Holyoke Chair, an uncomfortable[5] and precarious Jacobean cathedra reserved for such ceremonies since at least 1770 (when it was already some two hundred years old). Called "bizarre ... with a complex frame and top-heavy superstructure", its "square framework set on the single rear post makes [it] tip over easily to either side."[20] Said the Harvard Gazette in 2007, "When the chair holds its robed occupant, onlookers cannot detect the odd geometry by which its triangular seat points toward a square back rippling with knobby dowels and finials. Perhaps by striking their own precarious balance in this strange seat of authority, the successors of Edward Holyoke [Harvard's president 1737–69] come to sense what the job is all about."[upper-alpha 6]

Ceremonies

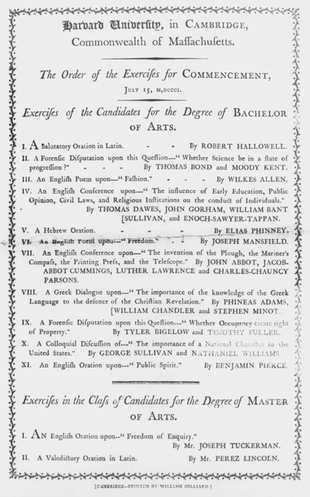

At the University Marshal's call ("Mister Sheriff, pray give us order") the Middlesex Sheriff takes to the dais, strikes it thrice with the butt of his staff, and intones, "The meeting will be in order."[5] Three student speakers (Undergraduate English, Undergraduate Latin, and Graduate English) are introduced and deliver their addresses.

Then, according to the order in which the various graduate and professional schools were created, the dean of each school steps forward to present, en masse, that school's degree candidates. Each group stands for the President's incantation conferring their degrees, which is followed by a traditional welcome or exhortation: doctoral graduates, for example, are welcomed "to the ancient and universal company of scholars", while law graduates are reminded to "aid in the shaping and application of those wise restraints that make us free." Last to be graduated are the Bachelor's candidates, who are then welcomed to "the fellowship of educated men and women."[1]

Honorary degrees are then bestowed. Finally, all rise to sing "The Harvard Hymn",[22][23] expressing the hope (Integri sint curators, Eruditi professores, Largiantur donatores—printed lyrics are supplied)[24] that the trustees, faculty and benefactors will manifest (respectively) integrity, wisdom, and generosity.[25] After a benediction is said, the Middlesex Sheriff declares the ceremony closed and the President's Procession departs.

Once the dais is clear the Harvard Band strikes up and the Memorial Church bell commences to peal,[23] joined by bells throughout Cambridge for most of the following hour.[upper-alpha 7]

Mid-day ceremonies

After the Morning Exercises, each graduate or professional school, and each upperclass House, holds a more intimate ceremony (with luncheon) at which its member-graduates are called forward by name to receive their diplomas in hand.

Alumni Association meeting and afternoon addresses

At the afternoon meeting of the Harvard Alumni Association, the President and the Commencement Day speaker deliver their addresses.

US Secretary of State (and former Army general) George C. Marshall's 1947 address as Commencement Day Speaker famously outlined a plan (soon known as the Marshall Plan, and for which he would later be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize) for the economic revival of post-World War II Europe.[26]

Historical notes

Sheriffs

"Our fathers ... closely associated the thirst for learning and that for beer", a 1924 Harvard history observed,[27] so that (a modern survey continued) the sheriffs' presence at Commencements "has a practical origin. Feasting, drinking, and merrymaking at earlier commencements often got out of hand. Fights were not unheard of", and commencements in various years have featured two-headed calves, an elephant, and Indians-versus-scholars archery competitions.[5] Such goings-on were sufficiently common knowledge that in 1749, Bostonian William Douglass explained to a general readership that the siege and capture of Louisbourg had been "carried on in a tumultuary random Manner, and resembled a Cambridge Commencement."[27]

Thus in 1781,

For the preservation of Disorders on Commencement day, [the Corporation] voted that the Honble Henry Gardner Esq: and the Honble Abraham Fuller Esq: Justices of the Peace thro' the State, and Loammi Baldwin Esq: Sheriff of the County of Middlesex, be requested to give their attendance on that day ...[15]

Earlier measures had included the 1693 banning of plum cake—the enjoyment of which, officials asserted, was unknown at other universities, "dishonourable to ye Colledge, not gratefull to Wise men, and chargable to [i.e. the fault of] ye Parents". This was one of many efforts by Increase Mather (Harvard's president from 1692 to 1701) toward "Reformation of those excesses ... [of] Commencement day and weeke at the Colledge, [sic] so that I might [prevent] disorder and profaneness"[1]—for Harvard officials a recurring headache.[upper-alpha 8]

Sartorial regulations

To curb unseemly sartorial displays of wealth and social status the 1807 Laws of Harvard College provided that, on Commencement day,

[E]very Candidate for a first degree shall be clothed in a black gown, or in a coat of blue grey, a dark blue, or a black color; and no one shall wear any silk nightgown, on said day, nor any gold or silver lace, cord, or edging upon his hat, waistcoat, or any other part of his clothing, in the College, or town of Cambridge.[25]

George Bernard Shaw

Responding to the prospect of being nominated for an honorary degree on the occasion of Harvard's Tercentenary in 1936, George Bernard Shaw wrote:

Dear Sir, I have to thank you for your proposal to present me as a candidate for an honorary degree of D.L. of Harvard University at its tri-centenary celebration. But I cannot pretend that it would be fair for me to accept university degrees when every public reference of mine to our educational system, and especially to the influence of the universities on it, is fiercely hostile. If Harvard would celebrate its three hundredth anniversary by burning itself to the ground and sowing its site with salt, the ceremony would give me the greatest satisfaction as an example to all the other famous old corrupters of youth, including Yale, Oxford, Cambridge, the Sorbonne, etc. Under these circumstances I should let you down very heavily if you undertook to sponsor me.

A handwritten postscript read: "I appreciate the friendliness of your attitude."[28]

See also

Notes

- ↑ [4][1] "The first Commencement took place in 1642," noted Harvard's Commencement director in 2007. "The difference between 365 years and 356 commencements is accounted for by wars and plagues that cancelled the event."[5]

- ↑ [8] Degree-granting exercises were held in Sanders Theatre from the late nineteenth century through the early twentieth centuries, and prior to that in a succession of locations.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The governor and sheriffs are among several public officials, not otherwise affiliated with Harvard, who have long taken part in the ceremonies.[15] By tradition the Middlesex Sheriff closes the ceremony by crying, "The meeting is adjourned," though in 1997 Sheriff James DiPaola, "in his first Harvard Commencement and clearly enjoying his role, wanted more lines. At the end he boomed, 'Marshal! As the sheriff of Middlesex County, I have news! The meeting is adjourned!'"[16] Not all outside participants have been wholeheartedly enthusiastic. In the 1930s Governor Paul Dever, to the chagrin of Harvard officials and alumni, shunned the prescribed morning coat for a regular tuxedo and straw hat, and Governor James Michael Curley appeared in silk stockings, knee britches, powdered wig, and a tricorn hat with plume. (When challenged by Harvard officials—"the story goes", according to the Harvard Crimson—Curley produced the Massachusetts Bay Colony's statutes covering Harvard Commencement dress, and on the basis of its authority claimed to be the only person present who was properly attired.) In 1970 Middlesex Sheriff John J. Buckley objected to the traditional costume he would be required to wear. After Suffolk Sheriff Thomas S. Eisenstadt was asked to open and close in Buckley's stead, Cambridge mayor Alfred Vellucci mused, "Now I see they're going to have Tom Eisenstadt march with the sword. Where is he going to get a sword unless he borrows one from the Don Juan Drum and Bugle Corps?"[17]

- ↑ "[Morris Hicky Morgan] was the first regular University Marshal, with the title of Marshal of Commencement from 1896 to 1908 and of University Marshal until his death in March 1910. A Chief Marshal had been appointed for the Bicentennial Celebration in 1836 and for the 250th Celebration in 1886. It has not been discovered who ran ordinary academic exercises before 1896; probably an ad hoc Marshal was appointed," wrote Mason Hammond in the Harvard Library bulletin.[14]

- ↑ "As recently as Francis Sargent's 1970 attendance, the Governor of Massachusetts traditionally arrived at Commencement with 17th-century mounted, scarlet-coated guard, which escorted him from the State House to the Johnston Gate. The guard bore pikes, somewhat less useful today than when Governor Thomas Dudley rode to the first Commencement despite warnings of possible ambush by Indians."[1]

- ↑ [19] Measuring 46.5 in (118 cm) high and 32.5 in (83 cm) wide, its seat about 20 inches (51 cm) from the floor and about as deep, the Holyoke Chair is thought to have been made in England or Wales between 1550 and 1600.[20] "[A] display of virtuoso turning," it was bought for Harvard by Holyoke, who saw it as "suitable to the authority of the president and establishing an iconographic link between Harvard College and its late-medieval English prototypes, Oxford and Cambridge," in the words of Jonathan Fairbanks and Robert Trent. Although the "thronelike quality [lends] an official air, [chairs of this design] were undoubtedly domestic chairs originally",[20] and indeed (according to a 1903 New York Times article) its use by Holyoke was at first "merely as a serviceable piece of every-day furniture."[21] Even after its first recorded ceremonial use (at the 1770 installation of President Samuel Locke) the President's Chair "used to stand in the Harvard library [Gore Hall], where, according to tradition, it gave a student the right to kiss any young woman whom he was showing through the college and who throughtlessly sat down on it. Whether or not the privilege was often or ever taken advantage of the present generation has no means of knowing."[21] The Fogg Museum now has custody between ceremonial uses.[19]

- ↑ The other participating bells are those of Lowell House, the Harvard Business School's Baker Hall, Christ Church Cambridge, the Harvard Divinity School's Andover Hall, the Church of the New Jerusalem, First Church Congregational, First Parish Unitarian Universalist, St. Paul Roman Catholic Church, St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, University Lutheran Church, Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church, North Prospect United Church of Christ, and St. Anthony's Church.[13]

- ↑ In 1721, "For the preventing Extravagencies at Commencemts. [The Corporation voted] 1. That the Order ... phibiting any Scholar to have Plum-cake &c in his Study or Chamber [at] Commencement be strictly observed. 2. That all mix'd drink make with distill'd Spts be also phibited on the Same Penalty. 3. That the Presidt and Fellows be desired to exhort & direct the Scholars to be more moderate and frugall in the Entertainmts. 4. And that the publick dinner usual on the day after Commencmt be lessen'd or laid aside, as the Presidt and Fellows of the House [i.e. the Tutors] shall think most convenient." In 1722, the Corporation "took more stringent action still": "Whereas the Countrey in general and the College in Particular have bin under Such Circumstances, as call aloud for Humiliation, and all due manifestations of it; and that a Suitable retrenchmt of every thing that has the face of Exorbitance or [extravegence] in Expences, especially at Commencmt out to be endeavrd. And Whereas the preparations & pvisions that have bin wont to be made at those ties have bin the Occasin of no Small disorders; It is Agreed, and Voted, That henceforth no preparation nor Provision either of Plumb-Cake or rosted, boiled or baked Meats & Pyes of any kind shalbe made by any Commencer, nore shal any such have any distilled Liquors, or any Composition made therewth." "These regulations proving ineffectual," in 1726 the Corporation, "having now had some Discourse about the great Disorders & Immoralities yt have attended ye Publick Commencements; it is agreed yt ye Several Members of ye Corporation will Jndeavour to think of wt may be a proper method for ye preventing of such Disorders & Immoralities ..."[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Hightower, Marvin. "The Spirit & Spectacle of Harvard Commencement". Harvard University.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Morning Exercises". Harvard University Commencement Office. 2013.

- ↑ "Honorary Degrees". Harvard University. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ↑ Matthews, Albert (1917). "Harvard Commencement Days 1642–1916". Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts: 309–84.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Cromie, William J. (May 31, 2007). "Commencement feasting, customs, color date to medieval Europe". Harvard Gazette.

- ↑ "Yard Ceremony". Lowell House.

- ↑ Ireland, Corydon; Koch, Katie; Walsh, Colleen (May 26, 2011). "Moments that make Commencement". Harvard Gazette.

- ↑ "2013 Commencement Seating, Tercentenary Theater, Morning Exercises". Harvard University Commencement Office. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Graduate and Professional Schools". Harvard University Commencement Office.

- ↑ Callan, Richard L. (April 28, 1984). "100 Dears of Solitude: John Harvard Finishes His First Century". Harvard Crimson.

- ↑ Rose, Cynthia (May 1999). "Reading the Regalia: A guide to deciphering the academic dress code". Harvard Magazine.

- ↑ "Locations, Maps and Directions". Harvard University Commencement Office. 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sweeney, Sarah (May 26, 2010). "Commencement wonderment". Harvard Gazette.

- ↑ Hammond, Mason (Summer 1987). "Official Terms in Latin and English for Harvard College or University". Harvard Library bulletin XXXV (3) (Harvard University). pp. 294–310.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Matthews, Albert (1917). Harvard Commencement Days 1642–1916. Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. XVIII. Transactions 1915–1916 (April 1916). pp. 309–384.

- ↑ "John Harvard's Journal: Commencement Confetti". Harvard Magazine. July–August 1997.

- ↑ Epps, Garrett (June 10, 1970). "Sheriff Cops out on Commencement". Harvard Crimson.

- ↑ "The Charter of the President and Fellows of Harvard College".

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Hightower, Marvin (September 24, 2007). "The President's Chair". Harvard Gazette.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Fairbanks, Jonathan L; Trent, Robert (1982). New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century 3. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Department of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture. p. 512.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Harvard's Old Colonial Chair – Thirteen Presidents Have Used It in Turn". New York Times. February 22, 1903.

- ↑ James Bradstreet Greenough; John Knowles Paine. "The Harvard Hymn".

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Rossano, Cynthia W. (May–June 2000). "Grace Notes". Harvard Magazine.

- ↑ "John Harvard's Journal: Center of Attention". Harvard Magazine. July–August 2011.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Rossano, Cynthia (May 1997). "These Festival Rites". Harvard Magazine.

- ↑ Bethell, John T. (May 1997). "The Ultimate Commencement Address: The Making of George C. Marshall's "routine" speech"". Harvard Magazine.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Batchelder, Samuel F. (June 1921). "'The Student in Arms'—Old Style". The Harvard Graduates' Magazine XXIX (cxvi): 549–571,551.

- ↑ Bethell, John T. (1998). Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780674377332.