Hiram M. Chittenden Locks

|

Chittenden Locks and Lake Washington Ship Canal | |

|

| |

|

An aerial view of the locks, facing west | |

| Location | Salmon Bay, Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

| Built | 1906 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Other |

| Governing body | Army Corps of Engineers |

| NRHP Reference # | 78002751[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 14, 1978 |

The Hiram M. Chittenden Locks is a complex of locks that sits at the west end of Salmon Bay, part of Seattle, Washington's Lake Washington Ship Canal.[2] They are known locally as the Ballard Locks[3][4] after the neighborhood to the north. (Magnolia lies to the south.)

The locks and associated facilities serve three purposes:

- To maintain the water level of the fresh water Lake Washington and Lake Union at 20–22 feet (6.1–6.7 m) above sea level[2][3] (Puget Sound's mean low tide).

- To prevent the mixing of sea water from Puget Sound with the fresh water of the lakes (saltwater intrusion).[5]

- To move boats from the water level of the lakes to the water level of Puget Sound, and vice versa.[6]

The complex includes two locks, 30 ft × 150 ft (9.1 m × 45.7 m) (small) and 80 ft × 825 ft (24 m × 251 m) (large).[7] The complex also includes a 235 ft (72 m) spillway with six 32 ft × 12 ft (9.8 m × 3.7 m) gates to assist in water-level control.[7] A fish ladder is integrated into the locks for migration of anadromous fish, notably salmon.[6][8]

The grounds feature a visitors center,[9] as well as the Carl S. English, Jr., Botanical Gardens.[10]

Operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,[11] the locks were formally opened on July 4, 1917,[12] although the first ship passed on August 3, 1916.[13] They were named after U.S. Army Major Hiram Martin Chittenden, the Seattle District Engineer for the Corps of Engineers from April 1906 to September 1908.[9] They were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.[1]

The locks proper

As noted above, the complex includes two locks.[7] Using the small lock when boat traffic is low conserves fresh water during summer, when the lakes receive less inflow. Having two locks also allows one of the locks to be drained for maintenance without blocking all boat traffic. The large lock is drained for approximately 2-weeks, usually in November, and the small lock is drained for about the same period, usually in March.

The locks can elevate a 760-by-80-foot (232 m × 24 m) vessel 26 ft (7.9 m), from the level of Puget Sound at a very low tide to the level of freshwater Salmon Bay, in 10–15 minutes. The locks handle both pleasure boats and commercial vessels, ranging from kayaks to fishing boats returning from the Bering Sea to cargo ships. Over 1 million tons of cargo, fuel, building materials, and seafood products pass through the locks each year.[4]

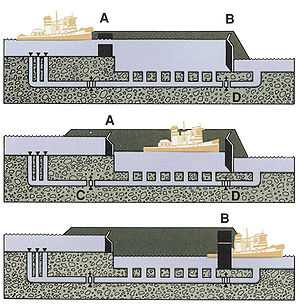

How the locks work

Vessels passing from the freshwater Lakes Washington and Union to Puget Sound enter the lock chamber through the open upper gates (A in the accompanying diagram). The lower gates (B) and the draining valve (D) are closed. The vessel is assisted by the lockwall attendants who assure it is tied down and ready for the chamber to be drained.[2]

Next, the upper gates (A) and the filling valve (C) are closed and the draining valve (D) is opened allowing water to drain via gravity out to Puget Sound.[2]

When the water pressure is equal on both sides of the gate, the lower gates (B) are opened, allowing the vessels to leave the lock chamber.[2]

The process is reversed for upstream locking.[2]

Spillway

South of the small lock is a spillway dam with tainter gates used to regulate the freshwater levels of the ship canal and lakes. The gates on the dam release or store water to maintain the lake within a 2 ft (0.61 m) range of 20 to 22 ft (6.1 to 6.7 m) above sea level. Maintaining this lake level is necessary for floating bridges, mooring facilities, and vessel clearances under bridges.[2]

"Smolt flumes" in the spillway help young salmon to pass safely downstream.[15] Higher water levels are maintained in the summer to accommodate recreation as well as to allow the lakes to act as a water storage basin in anticipation of drought conditions.[2]

Salt water barrier

If excessive salt water were allowed to migrate into Salmon Bay, the salt could eventually damage the freshwater ecosystem. To prevent this, a basin was dredged just above (east of) the large lock. The heavier salt water settles into the basin and drains through a pipe discharging downstream of the locks area. In 1975, the saltwater drain was modified to divert some salt water from the basin to the fish ladder, where it is added via a diffuser to the fish ladder attraction water; see below.[5]

To further restrict saltwater intrusion, in 1966, a hinged barrier was installed just upstream of the large lock. This hollow metal barrier is filled with air to remain in the upright position, blocking the heavier salt water. When necessary to accommodate deep-draft vessels, the barrier is flooded and sinks to the bottom of the chamber.[6]

Fish ladder

The fish ladder at the Chittenden locks is unusual—materials published by the federal government say "unique"—in being located where salt and fresh water meet. Normally, fish ladders are located entirely within fresh water.[16]

Pacific salmon are anadromous; they hatch in lakes, rivers, and streams—or, nowadays fish hatcheries—migrate to sea, and only at the end of their life return to fresh water to spawn. When the Corps of Engineers first built the locks and dam, they changed the natural drainage route of Lake Washington. The locks and dam blocked all salmon runs out of the Cedar River watershed. To correct this problem, the Corps built a fish ladder as the locks were constructed to allow salmon to pass around the locks and dam.[16]

The ladder was designed to use attraction water: fresh water flowing swiftly out the bottom of the fish ladder, in the direction opposite which anadromous fish migrate at the end of their lives. However, the attraction water from this first ladder was not effective. Instead, most salmon used the locks. This made them an easy target for predators; also, many were injured by hitting the walls and gates of the locks, or by hitting boat propellers.[16]

The Corps rebuilt the fish ladder in 1976 by increasing the flow of attraction water and adding more weirs: most weirs are now one foot higher than the previous one. The old fish ladder had only 10 "steps"; the new one has 21. A diffuser well mixes salt water gradually into the last 10 weirs. As a part of the rebuilding, the Corps also added an underground chamber with a viewing gallery.[15][16][17]

The fish approaching the ladder smell the attraction water, recognizing the scent of Lake Washington and its tributaries. They enter the ladder, and either jump over each of the 21 weirs or swim though tunnel-like openings. They exit the ladder into the fresh water of Salmon Bay. They continue following the waterway to the lake, river, or stream where they were born. Once there, the females lay eggs, which the males fertilize. Most salmon die shortly after spawning.[16][18]

The offspring remain in the fresh water until they are ready to migrate to the ocean as smolts. In a few years, the surviving adults return, climb the fish ladder, and reach their spawning ground to continue the life cycle.[18] Of the millions of young fish born, only a relative few survive to adulthood. Causes of death include natural predators, commercial and sport fishing, disease, low stream flows, poor water quality, flooding, and concentrated developments along streams and lakes.[19]

Visitors to the locks can observe the salmon through windows as they progress along their route. Although the viewing area is open year-round, the "peak" viewing time is during spawning season, from about the beginning of July through mid-August. A public art work, commissioned by the Seattle Arts Commission, provides literary interpretation of the experience through recordings of Seattle poet Judith Roche's "Salmon Suite," a sequence of five poems tied to the annual migratory sequence of the fish.

Gallery: Migratory fish

Among the species of salmonids migrating routinely through the ladder at the Chittenden Locks are Chinook (king) salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), Coho (silver) salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), Sockeye (red) salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), and steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss).[20]

Seattle salmon-run viewing schedule at the Seattle Fish Ladder. Sockeye – June, July; Chinook and Coho – Sept, Oct; steelhead – late fall and winter

-

Chinook: ocean phase

-

Chinook: male - freshwater phase

-

Sockeye: ocean phase

-

Sockeye: male - freshwater phase

-

Coho: ocean phase

-

Coho: male - freshwater phase

-

Steelhead: ocean phase

-

Steelhead: male - freshwater phase

Gallery: the facility

-

Dedication on 4 July 1917

-

The locks and the adjacent Commodore Park

-

Boat and barge in the large lock

-

Control tower

-

Boat entering the small lock

-

Tying off at the small lock

-

Fish ladder

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", p. 2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Ballard Locks". CityOfSeattle,net. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Lake Washington Ship Canal: Hiram M. Chittenden Locks" (2006), p. 6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", p. 2–3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", p. 3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", p. 8.

- ↑ "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder", passim.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", p. 4.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", p. 5.

- ↑ Sherrill Mausshardt and Glen Singleton, "Mitigating Salt-Water Intrusion through Hiram M. Chittenden Locks", Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal and Ocean Engineering, Vol. 121, No. 4, July/August 1995, pp. 224-227 , (doi 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(1995)121:4(224)). Abstract on site of American Society of Civil Engineers mentions that the locks are operated by the Corps. Accessed 21 September 2007.

- ↑ Walt Crowley, Turning Point 11: Borne on 4 July: The Saga of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, HistoryLink.org Essay 3425, July 3, 2001. Accessed 21 September 2007.

- ↑ Gordy Holt, Short Trips: Fascinating history sets the stage for a Ballard Locks outing, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Last updated August 15, 2007. Accessed 21 September 2007.

- ↑ "Chittenden Locks small chamber closing 12 days for annual maintenance (press release)" (Press release). US Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District. March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Lake Washington Ship Canal: Hiram M. Chittenden Locks" (2006), p. 8.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder", p. 2. This document is in the public domain, and some of the wording here is almost verbatim from the pamphlet.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder", p. 6.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder", p. 3.

- ↑ "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder", p. 4.

- ↑ "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder", p. 5–6.

References

- "Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks" (pamphlet), U.S. Government Printing Office: 1999-791-887. As work of the Federal Government, this document is in the public domain, and some of the wording in this article is almost verbatim from the pamphlet.

- "The Lake Washington Ship Canal Fish Ladder" (pamphlet), U.S. Government Printing Office: 1996-792-501. As work of the Federal Government, this document is in the public domain, and some of the wording in this article is almost verbatim from the pamphlet.

- "Lake Washington Ship Canal: Hiram M. Chittenden Locks" (pamphlet), US Army Corps of Engineers, 2006. As work of the Federal Government, this document is in the public domain, and some of the wording in this article is almost verbatim from the pamphlet.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hiram M. Chittenden Locks. |

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District: Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks

- Chittenden Locks on SeattleWiki

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 47°39′55.68″N 122°23′49.56″W / 47.6654667°N 122.3971000°W