Hilt

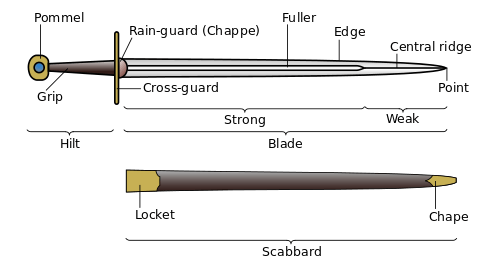

The hilt (rarely called the haft) of a sword is its handle, consisting of a guard, grip and pommel. The guard may contain a crossguard or quillons. A ricasso may also be present, but this is rarely the case. A tassel or sword knot may be attached to the guard or pommel.

Pommel

The pommel (Anglo-Norman pomel "little apple"[1]) is an enlarged fitting at the top of the handle. They were originally developed to prevent the sword slipping from the hand. From around the 11th century in Europe they became a counterweight to the blade.[2] This gave the sword a point of balance closer to the hilt allowing a more fluid fighting style. Depending on sword design and swordsmanship style, the pommel may also be used to strike the opponent (e.g., using the Mordhau technique).

Pommels have appeared in a wide variety of shapes, including oblate spheroids, crescents, disks, wheels, and animal or bird heads. They are often engraved or inlayed with various designs and occasionally gilt and mounted with jewels.

Ewart Oakeshott introduced a system of classification of medieval pommel forms in his The Sword in the Age of Chivalry (1964) to stand alongside his blade typology.[3] Oakeshott pommel types are enumerated with capital letters A–Z, with subtypes indicated by numerals.

- A: the "brazil-nut" pommel derived from the classical Viking sword

- B: a more rounded and shorter form of A. B1 is the variant with a straight lower edge, known as "mushroom" or "tea-cosy"

- C: "cocked-hat" form, derived from the Viking sword

- D: a bulkier and slightly later variant of C

- E: a variant of D with an angular top

- F: a more angular variant of E

- G: a plain disk. G1 and G2 are disk pommels ornamented with flower-shaped or shell-like ornaments, respectively, both particular to Italy

- H: a disk with the edges chamfered off. One of the most common forms, found throughout the 10th to 15th centuries. H1 is an oval variant.

- I: a disk with wide chamfered edges, the inner disk being much smaller than in H. I1 is a hexagonal variant

- J: as I, but with the chamfered edges deeply hollowed out. J1 is an elaborated form of the classic wheel-pommel

- K: a very wide and flat variant of J, popular in the late medieval period

- L: a tall type of trefoil shape; rare and probably limited to Spain in the 12th and 13th centuries

- M: a late derivation of the multi-lobed Viking pommel type, found frequently on tomb effigies during 1250-1350 in southern Scotland and northern England, but with few surviving examples

- N: boat-shaped, rare both in art and in surviving specimens

- O: a rare type of crescent-shape

- P: a rare shield-shaped form only known from a statue at Nuremberg cathedral

- Q: flower-shaped pommels, only known from artistic depictions of swords

- R: rare spherical pommel, mostly seen in the 9th and 10th centuries

- S: a rare type in the form of a cube with the corners cut off

- T: the "fig" or "pear" or "scent-stopper" shape, first found in the early 14th century, but seen with any frequency only after 1360, with numerous derived forms well into the 16th century. T1 to T5 are variants of this basic type

- U: "key-shaped" type of the later half of the 15th century

- V: the "fish-tail" pommel of the 15th century, with variants V1 and V2.

- W: a "misshapen wheel" shape

- Z: the "cat's head" shape, apparently exclusive to Venice

Grip

The grip is the handle of the sword. It was usually of wood or metal, and often covered with shagreen (untanned tough leather or shark skin). Shark skin proved to be the most durable in temperate climates but deteriorated in hot climates, and consequently rubber became popular in the latter half of the 19th century. Alternatively, many sword types opt for ray skin instead, referred to in katana construction as the "same". Whatever material covered the grip, it was usually both glued on and held on with wire wrapped around it in a helix.

Guard

It is a common misconception that the cross-guard protects the user's entire hand from the opponent's sword. Only with the abandonment of the shield and then the armoured gauntlet did a full hand guard become necessary. The crossguard still protected the user from a blade that was deliberately slid down the length of the blade to cut off or injure the hand.

Early swords do not have true guards but simply a form of stop to prevent the hand slipping up the blade when thrusting as they were invariably used in conjunction with a shield.

From the 11th century, European sword guards took the form of a straight crossbar (later called "quillon") perpendicular to the blade.

Beginning in the 16th century in Europe, guards became more and more elaborate, with additional loops and curved bars or branches to protect the hand. Ultimately, the bars could be supplemented or replaced with metal plates that could be ornamentally pierced. The term "basket hilt" eventually came into vogue to describe such designs.

Simultaneously, emphasis upon the thrust attack with rapiers and smallswords revealed a vulnerability to thrusting. By the 17th century, guards were developed that incorporated a solid shield that surrounded the blade out to a diameter of up to two inches or more. Older forms of this guard retained the quillons or a single quillon, but later forms eliminated the quillons, altogether being referred to as a cup-hilt. This latter form is the basis of the guards of modern foils and épées.

Ricasso

The ricasso is a blunt section of blade just below the guard. On developed hilts it is protected by an extension of the guard.[4] On two-handed swords, the ricasso provided a third hand position, permitting the user's hands to be further apart for better leverage.

Sword knot

The sword knot or sword strap, sometimes called a tassel, is a lanyard—usually of leather but sometimes of woven gold or silver bullion, or more often metallic lace—looped around the hand to prevent the sword being lost if it is dropped. Although they have a practical function, sword knots often had a decorative design. For example, the British Army generally adopted a white leather strap with a large acorn knot made out of gold wire for infantry officers at the end of the 19th century; such acorn forms of tassels were said to be 'boxed', which was the way of securing the fringe of the tassel along its bottom line such that the strands could not separate and become entangled or lost. Many sword knots were also made of silk with a fine, ornamental alloy gold or silver metal wire woven into it in a specified pattern.

The art and history of tassels are known by its French name, passementerie, or Posamenten as it was called in German. The military output of the artisans called passementiers (ornamental braid, lace, cord, or trimmings makers) is evident in catalogs of various military uniform and regalia makers of centuries past. The broader art form of passementerie, with its divisions of Decor, Clergy and Nobility, Upholstery, Coaches and Livery, and Military, is covered in a few books on that subject, none of which are in English.

Indian swords had the tassel attached through an eyelet at the end of the pommel.

Chinese swords, both jian and dao, often have lanyards or tassels attached. As with Western sword knots, these serve both decorative and practical functions, and the manipulation of the tassel is a part of some jian performances.

References

- ↑ In Old French of an ornamental knob from the late 11th century, attested for the pommel of a sword in the late 12th century, of the pommel of a saddle in the mid-15th century. Compare Middle Latin pomellum, pomellus "knob, boss" (12th century).

- ↑ Loades, Mike (2010). Swords and Swordsmen. Great Britain: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84884-133-8.

- ↑ See also myarmoury.com for an online summary.

- ↑ David Haring, ed. "The Complete Encyclopedia of Weapons" Gallery Press, 1980, p. 48