High Speed 2

| High Speed 2 | |

|---|---|

|

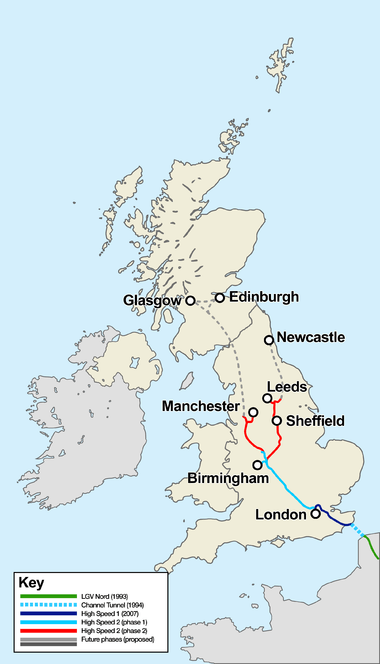

Preliminary High Speed 2, High Speed 1 and Channel Tunnel Rail links | |

| Overview | |

| Type | High-speed railway |

| System | National Rail |

| Status | Planned for 2026 (phase 1) and 2032-3 (phase 2) |

| Locale |

England Phase 1: Greater London, West Midlands Phase 2: North West, Yorkshire Potential future phases: North East, Scotland |

| Termini |

London Euston Phase 1: Birmingham Curzon Street & WCML connection near Rugeley Phase 2: Manchester Piccadilly & Leeds New Lane Potential future termini: Newcastle Central, Edinburgh Waverley and Glasgow Central |

| Stations | 4 (phase 1) |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 192 kilometres (119 mi) (phase 1, to WCML connection) |

| No. of tracks | Double track throughout |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Loading gauge | GC |

| Electrification | 25 kV AC overhead |

| Operating speed | Up to 400 km/h (250 mph)[1] |

| High Speed 2 route diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

High Speed 2 (HS2) is a planned[2][3] high-speed railway between London Euston, the English Midlands, North West England, Yorkshire, and potentially North East England and the Central Belt of Scotland.

The project is being developed by High Speed Two (HS2) Ltd, a company limited by guarantee and established by the UK government. The line, if fully approved, is anticipated to be built in two phases. The first phase will be between London and Birmingham. The second phase is to complete the sections from Birmingham each side of the Pennines to Manchester and Leeds. The western leg is to Manchester Piccadilly running under Crewe railway station via a tunnel bypassing the rail junction completely and via a new Manchester Airport station. The eastern leg is to Leeds via the East Midlands Hub and Sheffield Meadowhall. Four city centres will be served directly: Birmingham, Leeds, London and Manchester. Services to Liverpool, Crewe, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Preston, Lancaster and Carlisle are to be accessed using HS2 trains running on existing slower classic tracks or edge-of-town HS2 stations.

High-speed rail is officially supported in principle by the Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties, and opposed by UK Independence Party and the Green Party. Some Labour and Conservative politicians do not support their party line, and oppose the HS2 scheme in detail; some reject the whole principle of high-speed rail. The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government formed in May 2010 stated in its initial programme for government its commitment to creating a high-speed rail network.[4] In January 2012 the construction of phase 1 between London and Birmingham was approved. Construction is set to begin in 2017 with an indicated opening date of 2026. In January 2013 the preliminary phase 2 route was announced with a planned completion date of 2032. The cost is estimated by the Department for Transport to be £43 billion; a study by the Institute of Economic Affairs suggested a total cost of £80 billion. On English soil a comparable development is HS1.

Although parliamentary approval has been given for the phases of construction, precise details of the plan, and route, have not been formalised being still open to negotiation. For example, the spur to Heathrow airport was dropped from phases one and two in March 2015.[5]

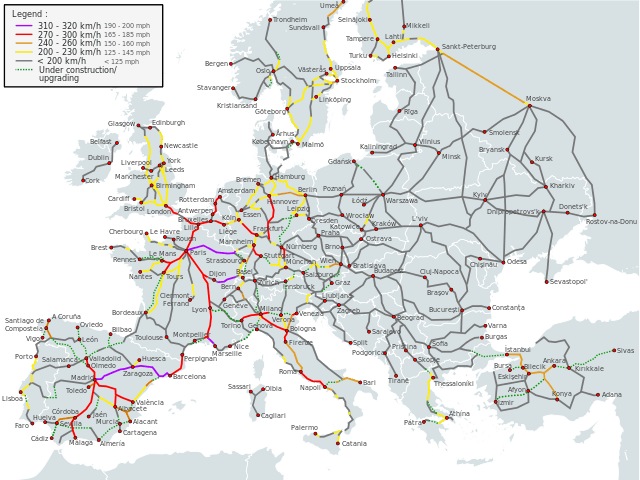

History

High-speed rail has been expanding across the European Union since the 1980s, with several member countries – notably France, Spain and Germany – investing heavily in new lines capable of operating at over 270 kilometres per hour (170 mph). In 2009 there were reportedly 5,600 kilometres (3,480 mi) of high-speed line in operation in Europe; a further 3,480 kilometres (2,160 mi) were under construction and another 8,500 kilometres (5,280 mi) were planned.[6]

High-speed rail arrived in the United Kingdom with the opening in 2003 of the first part of High Speed 1 (then known as the 108-kilometre (67 mi) Channel Tunnel Rail Link) between London and the Channel Tunnel. The development of a second high-speed line was proposed in 2009 by the United Kingdom Government to address capacity constraints on the West Coast Main Line railway, which is forecast to be at full capacity in 2025.[7] Most of the rail network in Britain consists of lines constructed during the Victorian era, which are limited to speeds no greater than 200 kilometres per hour (125 mph). A document published by the Department for Transport in January 2009 described an increase of 50% in rail passenger traffic and an increase of 40% in freight in the preceding 10 years in the UK and detailed several infrastructure problems. The report proposed that new high-speed lines be constructed to address these issues and, following assessment of various options,[8] concluded that the most appropriate initial route for a new line was from London to the West Midlands.[9]

High Speed Two Limited

In January 2009 the Labour government established High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd), chaired by Sir David Rowlands,[10] to examine the case for a new high-speed line and present a potential route between London and the West Midlands.[11] The government report suggested that the line could be extended to reach Scotland.[12]

Drawing on consultations carried out for the Department for Transport (DfT) and Network Rail, HS2 Ltd would provide advice on options for a Heathrow International interchange station, access to central London, connectivity with HS1 and the existing rail network, and financing and construction,[13] and report to the government on the first stage by the end of 2009.[14]

In August 2009 Network Rail published its own study independent of HS2's work, outlining somewhat different proposals for the expansion of the railway network, which included a new high-speed rail line between London and Glasgow/Edinburgh, following a route through the West Midlands and the North-West of England.[15]

For the HS2 report, a route was investigated to an accuracy of 0.5 metres (18 in).[16] In December 2009 HS2 presented its report to the government. The study investigated the possibility of links to Heathrow Airport and connections with Crossrail, the Great Western Main Line, and the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (HS1), as displayed in the map shown.

On 11 March 2010 the HS2 report and supporting studies were published, together with the government's command paper on high-speed rail.[17][18]

Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government review

The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition, on taking office in May 2010, undertook a review of HS2 plans inherited from the previous government. The Conservative Party in opposition had backed the idea of a high-speed terminus at St Pancras with a direct link to Heathrow Airport[19] and had adopted a policy to connect London, Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham with Heathrow by high-speed rail with construction starting in 2015.[20] In March 2010 Theresa Villiers had stated "The idea that some kind of Wormwood Scrubs International station is the best rail solution for Heathrow is just not credible".[21]

The new Secretary of State for Transport, Philip Hammond, asked Lord Mawhinney, a former Conservative Transport Secretary, to conduct an urgent review of the proposed route. The coalition government wished the high-speed line to be routed via Heathrow Airport, an idea rejected by HS2 Ltd.[22]

Mawhinney's conclusions contradicted Villiers' view and Conservative policy in opposition, stating that HS2 should not go to Heathrow Airport until it reaches northern England. Routing the whole line via Heathrow would add seven minutes to the journey time of all services.[23]

In December 2008 an article in The Economist noted the increasing political popularity of high-speed rail in Britain as a solution to transport congestion, and as an alternative to unpopular schemes such as road-tolls and runway expansion, but concluded that its future would depend on it being commercially viable.[24] In November 2010 Philip Hammond stated that government support for HS2 did not require it to break even directly (financially), what The Economist had called the "financial viability" test for new rail infrastructure:

If we used financial accounting we would never have any public spending, we would build nothing ... Financial accounting would strike a dagger through the whole case for public sector investment.[25]

Public consultation

On 20 December 2010 the government published a slightly revised line of route for public consultation,[26][27] based on a Y-shaped route from London to Birmingham with branches to Leeds and Manchester, as originally put forward by Lord Adonis as Secretary of State for Transport under the previous government,[28] with alterations designed to minimise the visual, noise, and other environmental impacts of the line.[26] In a statement to parliament, the Secretary of State confirmed that the first phase of construction would include a high-speed line from London to Birmingham as well as a connection to High Speed 1. High-speed lines north of the West Midlands would be built in later stages, and a link to Heathrow Airport would be initially provided by a connection at Old Oak Common, with a high-speed link to the airport to be added later. The high-speed line would connect to the existing network, allowing through trains from London to northern destinations.[29][30] The consultation documents were published on 11 February 2011 and the consultation period was set to run until July 2011.[31] When the results were published, they revealed that over 90% of respondents to the consultation were against HS2.

Decision to proceed with HS2

In January 2012 the Secretary of State for Transport announced that HS2 would go ahead. It would comprise a 'Y-shaped' network with stations at London, Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield and the East Midlands conveying up to 26,000 people each hour at speeds of up to 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph). It would be built in two stages. Phase one would be a 225 km (140 mi) route from London to the West Midlands which would be constructed by 2026. Phase two, from Birmingham to both Leeds and Manchester, would be constructed by 2033. Consultation on this phase would begin in early 2014 with a final route chosen by the end of 2014. Additional tunnelling and other measures to meet local communities' and environmental concerns were also announced.[3] The legislative process would be achieved through two hybrid bills, one for each phase.[32]

Legal challenges

At the end of March 2012 the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust (BBOWT) announced that it had submitted a complaint to the European Commission that the UK government, in failing to carry out a strategic environmental assessment ahead of deciding on the route of Phase 1 of HS2, was in breach of European Union legislation. BBOWT said that the complaint would only be considered by the EU Commission after the UK Courts had concluded consideration of various judicial reviews submitted to them.[33]

In April 2012 five requests for judicial review were submitted, two by HS2 Action Alliance (HS2AA) and one each by the 51m Group, Aylesbury Park Golf Club, and Heathrow Hub Ltd. In its applications HS2AA claimed that the government failed to carry out a proper strategic environmental assessment and that it provided inadequate information to the public during the public consultation. As a consequence the HS2AA claimed that the Secretary of State's decision to approve Phase 1 of HS2 was made without proper justification, that it ignored the government's own processes and assessment criteria, and relied on undisclosed material.[34] In a separate judicial review request the 51m Group challenged the government on several grounds. Firstly, that it failed to consult properly on the original or the revised route. Secondly, that it failed to consider the impact of HS2 on the London Underground network. Thirdly, that it did not take proper account of the environmental impact on the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and several important wildlife habitats, and finally that the hybrid bill approach was 'incompatible with the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive.[35][36] Aylesbury Park Golf Club's proceedings are based on the impact of the proposed route which will pass through part of the club.[37] Heathrow Hub Ltd, a company owned by Arup, announced it has also started proceedings on the grounds that the UK Government could choose an alternative route which would provide an improved connection between HS2 and Crossrail via a transport hub built on land owned by the company.[38]

At the end of July 2012 a High Court Judge gave permission for the five judicial reviews to proceed with individual hearings set for an eight-day period in early December 2012. The judge confirmed that the cases of the HS2AA, 51M and Heathrow Hub, whose consultation responses had been lost by HS2 Ltd, could be amended to incorporate this defect in their claims. A further hearing was set for October 2012 for the Government to explain its continued refusal to release passenger data relating to the West Coast Main Line.[39]

On 15 March 2013 Mr Justice Ouseley rejected all but one of the claims. In paragraph 843 of the judgment he concluded that "The consultation process in respect of blight and compensation was all in all so unfair as to be unlawful."[40] Permission to appeal has been granted on two grounds: applicability of Strategic Environmental Assessment to the project and re-consultation of 'optimised alternative'.[41]

A further rebuff by the court of appeal in July 2013 meant the prospect of a showdown at the Supreme Court.[42]

Route

Phase 1 – London to the West Midlands

As proposed in March 2010, the line would run from London Euston, mainly in a tunnel, to an interchange with Crossrail west of London Paddington, then along the New North Main Line (Acton-Northolt Line) past West Ruislip and alongside the Chiltern Main Line with a 4.0-kilometre (2.5 mi) viaduct over the Grand Union Canal and River Colne, and then from the M25 to Amersham in a new 9.7-kilometre (6 mi) tunnel. After emerging from the tunnel, the line would run parallel to the existing A413 road and London to Aylesbury Line, through the 47-kilometre (29 mi) wide Chiltern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, passing close by Great Missenden to the east, alongside Wendover immediately to the west, then on to Aylesbury. After Aylesbury, the line would run alongside the Aylesbury – Verney Junction line, joining it north of Quainton Road and then striking out to the north-west across open countryside through North Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, South Northamptonshire, Warwickshire and Staffordshire. Several alignments were studied, and in September 2010 HS2 Ltd set out recommendations for altering the course at certain locations.[43]

In December 2010 the Transport Secretary announced several amendments to the route aimed at mitigating vibration, noise, or visual impact. These changes include, at Primrose Hill, in north London, moving the tunnel 100 metres (330 ft) further north, and in west London reducing the width of the Northolt Corridor; lowering the alignment and creating a 900-metre (3,000 ft) green tunnel in Buckinghamshire at South Heath; at nearby Amersham, where two footpaths would otherwise be severed, at Chipping Warden in Northamptonshire and Burton Green in Warwickshire, green bridges would be constructed; the alignment would be moved away from the settlements of Brackley, in Northamptonshire, Ladbroke and Stoneleigh in Warwickshire and Lichfield in southern Staffordshire, and from the Grade I listed buildings Hartwell House in Buckinghamshire and Edgcote House in Northamptonshire.[44]

In January 2012 the Transport Secretary announced further revisions to the Phase 1 route. The key revisions included a new 4.3-kilometre (2.7 mi) tunnel at South Ruislip avoiding the Chiltern Line and mitigating the impact in the Ruislip area; realignment of the route and extension of the continuous tunnel, originally from the M25 to Amersham, to near Little Missenden; at Wendover and nearby South Heath extension to the green tunnels to reduce impact on local communities; an extension to the green tunnel beside Chipping Warden and Aston Le Walls; and realignment to avoid heritage sites around Edgcote. The revised route would comprise 36.2 kilometres (22.5 mi) in tunnel or green tunnel compared to 23.3 kilometres (14.5 mi), a 55% increase. Overall, 127 km (79 mi) of the 230-kilometre (140 mi) route will be in tunnel or cutting, while 64 kilometres (40 mi) will be on viaduct or embankment, a reduction of 16 kilometres (10 mi) from the route in the original consultation documents.[2][3]

In April 2013 a decision by HS2 Ltd and the Department for Transport to recommend further bore tunnelling under the 9-kilometre (6 mi) 'Northolt Corridor' in the London Borough of Ealing was announced in an HS2 Ltd press release. The tunnel will minimise blight for residents and businesses and eliminate the substantial impact of traffic which a surface route would otherwise have caused.[45] The further bore tunnelling will link up the tunnels already planned beneath South Ruislip and Ruislip Gardens and Old Oak Common to North Acton. HS2 Ltd found in a study they had undertaken that bore tunnelling this specific stretch of the HS2 route will take 15 months less time than constructing a surface HS2 route through this area would have done, and in addition will be at least cost neutral. The cost neutrality is due to the fact that 20 bridge replacements, including three and a half years to replace both road bridges at the Hanger Lane Gyratory System, amenity disruption, the construction of two tunnel portals and the likelihood of substantial compensation payments will all be avoided.[46] The proposed tunnel will be included as the preferred option in the draft Environmental Statement for the first phase of HS2. The decision to recommend tunnelling the section of HS2 route through the London Borough of Ealing has been well received and has been billed as a victory for local residents and local grassroots activism.[47][48] In addition to preventing blight to homes, schools and businesses the decision will also help to preserve the tranquility of Perivale Wood, an ancient wood, bird sanctuary and Britain's second oldest nature reserve,[49] Tunnelling HS2 in this section of the route will additionally free up the New North Main Line for future local rail services.

Heathrow access

Proposals have been considered for several years for the construction of a spur connecting the HS2 route to Heathrow Airport.

While in opposition, the Conservative Party outlined plans in their 2009 policy paper to construct a high-speed line connecting London to Birmingham, Leeds and Manchester, with connections to cities on the Great Western main line (Bristol and Cardiff) and a long-term aim of linking to Scotland. It also expressed support for a plan put forward by the engineering firm Arup for a new Heathrow Hub which would include a link connecting Heathrow Airport to the new high-speed rail route and to the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, with the possibility of connections to European destinations.[50]

Arup had previously suggested in Heathrow Hub Arup Submission to HS2 that a 80-hectare (200-acre) site at the Thorney part of Iver, north-east of the intersection of the M25 and M4, could house a railway station of 12 or more platforms, as well as a coach and bus station and a 6th airport terminal. Under this proposal, the high-speed line would then follow a different route to Birmingham, running parallel to existing motorways and railways as with HS1 in Kent.[51]

According to Lord Mawhinney's July 2010 report, the Heathrow station should be directly beneath Heathrow Central station (not at Iver, as proposed by Arup) and the London terminus for HS2 should be at the 2018 Crossrail station Old Oak Common, not Euston.[52] This plan, properly named "A Heathrow Hub with Old Oak Common terminus", was initially supported by the Conservative Party,[53] although in the final consultation plan, HS2 was proposed to terminate at Euston with a high-speed spur to Heathrow.[54]

In December 2010 the government announced that a high-speed connection with Heathrow Airport would be built as part of the second phase of the project and that until then connections would be made at Old Oak Common, where HS2 would have an interchange station with the Heathrow Express and Crossrail. However, in March 2015 transport minister Patrick McLoughlin stated to the House of Commons that the proposed Heathrow spur would no longer be considered as part of Phase 1 or Phase 2 of the HS2 scheme.[55]

Phase 2 – West Midlands to Manchester and Leeds

Phase 2 envisages a Y-shaped route extending north of Birmingham to Manchester and Leeds.[56][57] Consultation on the route is planned to take place in 2014, and the line is expected to be built by 2033.[3] The Leeds branch would diverge just north of Coleshill and head in a north-easterly direction roughly parallel to the M42 motorway. A high speed spur line will serve the new Leeds New Lane railway station, with the main line of the branch heading north-east to meet the East Coast Main Line near York.[58]

The Manchester branch would be an extension of the Phase 1 line north of Lichfield beyond the connecting spur to the West Coast Main Line (WCML). The line will continue north, with a second connection to the WCML at Crewe, although there will be no high-speed station there.[59] At Millington in Cheshire, the line will divide at a triangular junction, with the Manchester branch veering east, a connecting spur to the West Coast Main Line and a third line linking the Manchester branch to the West Coast route. Close to Manchester Airport, the route will enter a 16-kilometre (10 mi) tunnel, emerging at Ardwick where the line will continue to its terminus at Manchester Piccadilly.

The route to the West Midlands will be the first stage of a line to Scotland,[60] and passengers travelling to or from Scotland will be able to use through trains with a saving of 45 minutes from day one.[61] It was recommended by a Parliamentary select committee on HS2 in November 2011 that a statutory clause should be in the bill that will guarantee HS2 being constructed beyond Birmingham so that the economic benefits are spread farther.[62]

Future phases – Scotland / Newcastle / Liverpool

In Scotland, business and governmental organisations including Network Rail, CBI Scotland and Transport Scotland (the transport agency of the Scottish Government) formed the Scottish Partnership Group for High-Speed Rail in 2001 to campaign for the extension of the HS2 project north to Edinburgh and Glasgow.[63] The Scottish Partnership Group published a study which outlined a case for extending high-speed rail to Scotland, proposing a route north of Manchester to Edinburgh and Glasgow as well as an extension to Newcastle.[64] At present there are no DfT proposals to extend high-speed lines north of either Leeds or Manchester or to Liverpool.

In November 2012 the Scottish Government announced plans to build a 74 km (46 mi) high-speed rail link between Edinburgh and Glasgow. The proposed link would reduce journey times between the two cities to under 30 minutes and is planned to open by 2024, eventually connecting to the high-speed network being developed in England.[65]

Proposed service pattern

The Department for Transport's economic case for HS2, updated for Phase 2, gives a provisional service pattern:[66]

| Start | Destination | Trains per hour | Intermediate stations |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Euston and Old Oak Common | Birmingham Curzon Street | Three | Birmingham Interchange |

| Start | Destination | Trains per hour | Intermediate stations |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Euston and Old Oak Common | Curzon Street | Three | Birmingham Interchange (2tph) |

| Manchester Piccadilly | Three | Birmingham Interchange and Manchester Airport (1tph), Manchester Airport only (1tph) | |

| Leeds New Lane | Three | Birmingham Interchange, East Midlands Hub and Meadowhall (1tph), East Midlands Hub only (1tph), East Midlands Hub and Meadowhall (1tph)[lower-alpha 1] |

Connection to other lines

Existing main lines

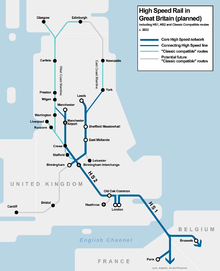

A key feature of the HS2 proposals is that the new lines will include connections to existing, standard-speed main lines. It is proposed that these connections will allow the running of special "classic compatible" trains which are capable of operating on both high-speed lines - at the same speed as "captive" trains - and on "classic" lines – at speeds of 200 kph (125 mph) or below. This will enable rail services to operate via HS2 which will run directly to destinations beyond the high speed network such as Liverpool, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Newcastle. The proposed connections will be at junctions on the phase 2 network at the following locations:[67]

- West Coast Main Line[67]

- east of Lichfield Trent Valley, 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) north-west of Lichfield

- south of Crewe

- south of Wigan North Western

- East Coast Main Line

- at Ulleskelf 5 miles (8.0 km) south east York, joining the existing Church Fenton line

- 2 miles (3.2 km) north of that the line meets the East Coast Main Line at Colton Junction near Colton, North Yorkshire.[58]

High Speed 1

The proposed route of HS2 into London will bring the line very close to the existing High Speed 1 line which terminates at St Pancras station; at their closest points, the two high-speed lines will be only 0.4 miles (0.64 km) apart. The Department for Transport has outlined plans to link the two high-speed lines in order to allow HS2 trains from the North of England to bypass London Euston and connect straight to HS1. This connection would enable direct rail services to be run from Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham to Paris, Brussels and other continental European destinations, realising the aims of the Regional Eurostar scheme, first proposed in the 1980s.[68]

Several possible solutions were considered. In 2010 the Government command paper stated:

…the new British high speed rail network should be connected to the wider European high speed rail network via High Speed One and the Channel Tunnel, subject to cost and value for money. This could be achieved through either or both of a dedicated rapid transport system linking Euston and St Pancras and a direct rail link to High Speed One.[69]

The March 2010 engineering study conducted by Arup for HS2 Ltd costed a "classic speed" GC loading gauge direct HS2-HS1 rail link at £458m (single track) or £812m (double track). This link would go from Old Oak Common feeding into the High Speed 1 network at St Pancras, via tunnel and the North London Line with a high-level junction north of St Pancras station for non-stopping services. The study found that double-track high-speed connection on the same route would cost £3.6bn (4.4 times greater than for classic speed).[70] The Department for Transport HS2 report of the same date recommended that, if a direct rail link is built, it should be the classic-speed, double-track option.[71]

This route proposal was supported by Arup's final report in December 2010, which concluded the best option would be to construct a tunnel between Old Oak Common and Chalk Farm, and then to use existing widened lines along the North London Line to connect to HS1 north of St Pancras.[29][30] The proposed connection would be built to GC loading gauge and would not be suitable for trains running at high speed.[72] Detailed route plans published in January 2012 indicate a 2-kilometre (1.2 mi) link which runs from a tunnel exit just west of the former Primrose Hill railway station, eastwards along the route of the North London Line and joining HS2 at a bridge junction on the west side of York Way.[73]

Concerns were raised by Camden London Borough Council about the impact on housing, Camden Market and other local businesses from construction work and bridge widening along the proposed railway link.[74][75] In August 2012 the Secretary of State for Transport, Justine Greening, asked HS2 Ltd to consider alternative routes for connecting HS2 and HS1. An alternative scheme for the HS1-HS2 link was put forward by TfL, who proposed incorporating the link into the projected Crossrail 2 route (see below).[76] Prior to the debate on the HS2 Bill in Parliament, Sir David Higgins, chairman of HS2 Ltd, expressed the view that the Camden railway link was "sub-optimal" and recommended that it should be omitted from the parliamentary bill. He stated that HS2 passengers travelling from the North of England to continental Europe would be able to transfer easily from Euston to St Pancras by London Underground in order to continue their journey on HS1. He also recommended that alternative plans should be drawn up to link the high-speed lines in the future.[77][78] The Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, proposed that an HS1-HS2 link should be provided by boring a tunnel under Camden to reduce the impact on the local area.[79]

In order to mitigate the problems foreseen in Camden and to save £700 million from the budget, the 2 km HS1-HS2 link was removed from the High Speed Rail (London – West Midlands) Bill at the second reading stage.[80]

An alternative solution to the issue of linking HS1 and HS2 was suggested by a former director of projects at British Rail, Dick Keegan, who recommended in January 2013 that HS2 should not terminate at Euston but at Stratford International instead, offering direct links to HS1 and on to continental Europe and greater capacity. Rapid transit into central London would be provided from Stratford Regional station.[81]

Crossrail

After leaving Euston, some HS2 services are planned to connect with Crossrail (opening 2018) at Old Oak Common.[76]

Possible Crossrail 2

Should proposals for the north-south Crossrail 2 achieve funding, Transport for London have expressed an interest in constructing this to mitigate the distribution of arriving passengers from HS2 at Euston. TfL have examined route options for Crossrail 2 which could potentially incorporate a direct link to HS2, and the Mayor's Office suggested that a direct link between HS1 and HS2 could be achieved by modifying the Crossrail 2 route proposals and providing a direct rail link between the termini for the two high-speed rail lines at Euston and St Pancras stations.[76]

As a consequence of Crossrail 2 coming to Euston, major modifications would need to be made to the current redevelopment plans for Euston, geared solely to HS2 which does not provide sufficient capacity to deal with the additional passenger demand from its becoming a stop of Crossrail 2 as well as for certain HS2 services.[76]

High-speed Crewe hub

David Higgins the chairman of HS2 Ltd proposed a high-speed hub at Crewe. Crewe is currently a major rail junction with six radiating classic lines from the junction to: Scotland/Liverpool, Birmingham/London, Chester, Shrewsbury, Stoke and Manchester. The high-speed hub is to be sited to the south of the current Crewe station taking advantage of the classic lines radiating from the Crewe junction. Many more regions and cities can be accessed via a combination of HS2 and classic lines, giving overall superior journey times. The intention is for high-speed trains to run off the northbound HS2 line into the high-speed hub and out onto classic lines without passing though the bottleneck of the existing Crewe station, keeping line speeds as fast as possible. A new station is proposed as a part of the hub. David Higgins aims to have the HS2 line from Birmingham to Crewe and the high-speed Crewe Hub incorporated in the Phase 1 construction plan.[82][83][84]

Journey times

The DfT's latest revised estimates of journey times for some major destinations once the line has been built as far as Leeds and Manchester, set out in the January 2012 document High Speed Rail: Investing in Britain's Future – Decisions and Next Steps, are as follows:[85] The intermediate timings given after the section to Birmingham has been built (Phase 1) are taken from an earlier document. Times given for Manchester and Leeds are for trains via Birmingham: until Phase 2 almost all trains from these cities to/from London will continue to use direct 'classic' lines.

| London to/from: | Standard journey time before HS2: | Fastest journey time before HS2: | Standard journey time after HS2 Phase 1: | Standard journey time after HS2 Phase 2: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | 1:24 | 1:12[t 1] | 0:49 | no change |

| Manchester | 2:08 | 1:58[t 2] | 1:40 | 1:08 |

| Leeds | 2:20 | 1:59[t 3] | no change | 1:28 |

Estimated journey times for direct trains running between British cities and Paris were published by HS2 Ltd in 2012.[86] These estimates assume a high speed rail journey using both HS1 and both completed phases of HS2:

| Paris to/from: | Standard journey time before HS2: | Fastest journey time using HS1 & HS2: |

|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | 4:42 | 3:07 |

| Manchester | 5:37 | 3:38 |

| Leeds | 5:47 | 3:38 |

Faster journey times than those estimated for HS2 have been claimed by advocates of an alternative proposal to build a high-speed magnetic levitation train line, UK Ultraspeed. However, this scheme has not received any governmental support.[87]

Planned stations

London and Birmingham

Central London

Under the March 2010 scheme, HS2 will start from a rebuilt London Euston. The station will be extended to the south and west with significant construction above. Twenty-four platforms will serve High Speed and classic lines to the Midlands, with six underground lines. The connection with Crossrail at Old Oak Common in West London is designed to mitigate the extra burden on Euston, although Euston too would see its underground station rebuilt and integrated with Euston Square.[31][88] A rapid transit 'people mover' link between Euston and St Pancras might be provided[89] and it is proposed to route the proposed Crossrail 2 (Chelsea-Hackney line) via Euston to cope with increased passenger demand.[90][91]

A review by Lord Mawhinney suggested that HS2 should terminate at Old Oak Common, not Euston.[23] He questioned the sense of HS2 terminating at Euston, with HS1 at St Pancras and no through running connection between them.[23] The plans proposed a link via an upgraded section of the North London Line to enable three trains per hour to run through to High Speed 1 and towards the Channel Tunnel, bypassing Euston.[31]

West London

A report published in March 2010 proposed that all trains would stop at a "Crossrail interchange" near Old Oak Common, between Paddington and Acton Main Line, with connections for Crossrail, Heathrow Express, and the Great Western Main Line to Heathrow Airport, Reading, South West England and South Wales. The station might also have interchange with London Overground and Southern on the North London and West London Lines and also with London Underground's Central line.[92]

Mawhinney recommended that HS2 should terminate at Old Oak Common because of its good connections and to save the cost of tunnelling to Euston.[23]

The HS2 route published on 10 January 2012 included stations at both Euston and Old Oak Common.[93]

Bickenhill ("Birmingham Interchange")

The March 2010 report proposed that a new "Birmingham Interchange" station in rural Solihull, on the other side of the M42 motorway from the National Exhibition Centre, Birmingham International Airport and Birmingham International Station.[94] The interchange will be connected by a people mover to the other sites; the AirRail Link people mover already operates between Birmingham International station and the airport.

According to Birmingham Airport's chief executive Paul Kehoe, HS2 is a key element in increasing the number of flights using the airport, and patronage by inhabitants of London and the South-East, as HS2 will reduce travelling times to Birmingham Airport from London to under 40 minutes.[95]

Birmingham city centre

New Street station, the main station serving central Birmingham, has been described as operating at full capacity and being unable to accommodate new high-speed services. A new terminus for HS2, termed "Birmingham Curzon Street" in the government's command paper[96] and "Birmingham Fazeley Street" in the report produced by High Speed 2 Ltd, would be built on land between Moor Street Queensway and the site of Curzon Street Station. It would be reached via a spur line from a triangular junction with the HS2 main line at Coleshill.[97]

There are no plans for the Curzon Street/Fazeley Street terminus to be used by other rail services, but the station would be adjacent to Moor Street station and could be directly linked. A link to New Street station via a people mover with a journey time of two minutes is possible.[98] The walking route between New Street and Moor Street has been considered in the redevelopment of New Street station, which will have a new footbridge at its east entrance[99] The other city-centre station, Snow Hill, is just a couple of minutes' train journey from Moor Street station.

Development planning for the Fazeley Street quarter of Birmingham has changed as a result of HS2. Prior to announcement of the HS2 station, Birmingham City University had planned to build a new campus in Eastside.[100][101] The proposed Eastside development will now include a new museum quarter, with the original stone Curzon Street station building becoming a new museum of photography, fronting on to a new Curzon Square, which will also be home to Ikon 2 a museum of contemporary art.[102]

In addition, the Government proposes that there will be a depot at Washwood Heath, where 30 homes will be demolished to enable the development.[103]

Birmingham and Manchester (Phase 2)

Proposals for the station locations were announced on 28 January 2013.

Crewe

HS2 will pass through Staffordshire and Cheshire, in tunnel under Crewe station but not stopping there.[104] However, the HS2 line will be linked to the West Coast Main Line via a grade-separated junction just south of Crewe, enabling "classic compatible" trains exiting the high-speed line to call at the existing Crewe station.[59][105] The Crewe & Nantwich Guardian reported on 17 March 2014 that the chairman of HS2 has advocated a dedicated hub station in Crewe.[106]

Manchester Airport

A Manchester Interchange station is planned to serve Manchester Airport on the southern boundary of Manchester, next to Junction 5 of the M56 motorway on the northern side of the airport and approximately 2.4 kilometres (1.5 mi) north-west of Manchester Airport railway station.[104][107] Manchester Airport is the busiest airport outside the London region and offers more destinations than any British airport. An airport station was recommended by local authorities during the consultation stage.[108][109] The government agreed in January 2013 for an airport station but agreed only on the basis that private investment was involved, such as funding from the Manchester Airports Group to build the station. The average journey from London Euston to Manchester Airport would be 59 minutes.

Manchester city centre

The route will continue from the airport into Manchester city centre via a 12.1-kilometre (7.5 mi) bored tunnel under the dense urban districts of south Manchester before surfacing at Ardwick.[110][111][112] If built, it will represent one of the major engineering feats of HS2 and will be the longest rail tunnel to be built in the United Kingdom, surpassing the 10.0-kilometre (6.2 mi) High Speed 1 tunnel completed in 2004.[113] The 12.2 km (7.6 mi) twin-bore tunnel be at an average depth of 108 ft (33 m) and trains will travel at 228 kilometres per hour (142 mph) through the tunnel. The diameter size of the tunnel is dependent on the train speed and length of the tunnel.[114] It is envisaged both tunnels will be, as an 'absolute minimum', at least 7.25 metres in diameter to accommodate the high-speed trains.[115]

Up to 15 sites were put forward, including Sportcity, Pomona Island, expanding Deansgate railway station and re-configuring the grade-II listed Manchester Central into a station.[116] Three final sites made the long list: Manchester Piccadilly station, Salford Central station and a newly built station at Salford Middlewood Locks.[117] Three approaches were considered, one via the M62, one via the River Mersey and the other through south Manchester. Both Manchester and Salford City Council recommended routing High Speed 2 to Manchester Piccadilly to maximise economic potential and connectivity rather than building a new station at a greater cost and which could be isolated from existing transport links.[118]

HS2 will terminate at an upgraded Manchester Piccadilly station.[104] At least four new 1,300-foot-long (400 m) platforms will be built to accommodate the new high-speed trains in addition to the two platforms which are currently planned as part of the Northern Hub proposal.[109] It is envisaged Platform 1 under the existing listed train shed will also be converted to a fifth HS2 platform. The HS2 concourse will be connected to the existing concourse at Piccadilly. HS2 will reduce the average journey time from central Manchester to central London from 2 hours 8 minutes to 1 hour 8 minutes.

Birmingham and Leeds branch (Phase 2)

HS2 will reduce the average journey time from central Leeds to London from 2 hours 20 minutes to 1 hour 28 minutes.

East Midlands Hub

A new station – the East Midlands Hub – at Toton sidings in the East Midlands is proposed, which would be a parkway station,[note 1] to serve Nottingham, Derby and Leicester.[119] The Derbyshire and Nottingham Chamber supported high-speed rail coming to the East Midlands but was concerned that a parkway station instead of centrally located city stations would result in no overall net benefit in journey times.[119] East Midlands Parkway railway station was recently constructed on the Midland Main Line south of Derby and Nottingham – close to the proposed site in Toton – and is failing to hit its passenger targets by a substantial margin.[120]

Sheffield Meadowhall

HS2 would continue north to a station at Meadowhall Interchange in South Yorkshire, serving Sheffield and surrounding large towns such as Rotherham.

Leeds New Lane

HS2 would then continue north from Meadowhall through West Yorkshire toward York, with a spur to central Leeds with a new station called Leeds New Lane. This new station will link with Leeds railway station by a walkway, with the possibility of moving walkways.[58]

Development

Infrastructure

The Department for Transport report on High Speed Rail published in March 2010 sets out the specifications for a high-speed line. It will be built to a European structure gauge (as was HS1) and will conform to European Union technical standards for interoperability for high-speed rail[121] (EU Directive 96/48/EC). HS2 Ltd's report assumed a GC structure gauge for passenger capacity estimations,[122] with a maximum design speed of 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph).[1] Initially, trains would run at a maximum speed of 360 kilometres per hour (225 mph).[123]

The new line would release capacity for freight and more local, regional and commuter services on both the West Coast Main Line, East Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line.[124]

Signalling would be based on the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) with in-cab signalling, to resolve the visibility issues associated with lineside signals at speeds over 200 kilometres per hour (125 mph).

Platform height will be at the European standard of 760 millimetres (2 ft 6 in).[125]

Rolling stock

The rolling stock for HS2 has not yet been specified in any detail. The 2010 DfT government command paper outlined some requirements for the train design among its recommendations for design standards for the HS2 network. A photograph of a French AGV (Automotrice à grande vitesse) was used as an example of the latest high-speed rail technology. The paper addressed the particular problem of designing trains to continental European standards, which use taller and wider rolling stock, requiring a larger structure gauge than the rail network in Great Britain.

The report proposed the development of two new types of train to make best use of the line:[123]

- Wider and taller trains built to a European loading gauge, which would be confined to the high-speed network (including HS1 and HS2) and other lines cleared to their loading gauge.

- 'Classic compatible' trains, capable of high speed but built to a British loading gauge to permit them to leave the high-speed line to join conventional routes such as the West Coast Main Line, Midland Main Line and East Coast Main Line.[note 2] Such trains would allow running of HS2 services to the north of England and Scotland. HS2 Ltd has stated that, because of their non-standard nature, these classic-compatible trains were expected to be more expensive.[126]

Both types of train would have a maximum speed of at least 350 km/h (220 mph) and length of 200 metres (660 ft). Two units could be joined together for a 400-metre (1,300 ft) train, but only platforms specially built or rebuilt would be able to accommodate such long trains.[123]

The DfT report also considered the possibility of 'gauge clearance' work on non-high-speed lines as an alternative to 'classic compatible' trains. This work would involve extensive reconstruction of stations, tunnels and bridges and widening of clearances to allow European-profile trains to run beyond the high-speed network. The report concluded that although initial outlay on commissioning new rolling stock would be high, it would cost less than the widespread disruption of rebuilding large tracts of Britain's rail infrastructure.[123]

Maintenance depot

In April 2010 Arup was asked to develop proposals for the location, engineering specification and site layout of the Infrastructure Maintenance Depot (IMD). The general location of the IMD was identified as adjacent to, or within 10k of the intersection of HS2 and the East West Rail (EWR) route near Steeple Claydon/Calvert in Buckinghamshire. The feasibility of using the MoD site at Bicester as the IMD was also considered. Six potential sites were shortlisted and rated against the specification. The preferred site, called 'Thame Road' (at Claydon Junction), and a fall-back site, 'Great Pond' were announced in December 2010.[127] The nearby Calvert Waste Plant has also been identified for heat and power generation.[127]

Cost

The first 190-kilometre (120 mi) section, from London to Birmingham, was originally costed at between £15.8 and £17.4 billion,[128] and the entire Y-shaped 540-kilometre (335 mi) network at £30 billion.[128]

Upgrading existing lines from London to Birmingham instead of building HS2 would cost more (£20bn) and would provide only two-thirds the extra capacity of HS2, according to Adonis.[129]

June 2013 saw the projected cost rise by £10bn to £42.6bn[130] and, less than a week later, it was revealed that the DfT had been using an outdated model to estimate the productivity increases associated with the railway, which meant the project's economic benefits were overstated.[131] Peter Mandelson, a key advocate of HS2 when the Labour Party was in government, declared shortly thereafter that HS2 would be an "expensive mistake",[132] and also admitted that the inception of HS2 was "politically driven" to "paint an upbeat view of the future" following the financial crash. He further admitted that the original cost estimates were "almost entirely speculative" and that "[p]erhaps the most glaring gap in the analysis presented to us at the time were the alternative ways of spending £30bn."[133] Boris Johnson similarly warned that the costs of the scheme would be in excess of £70 billion.[134] The Institute of Economic Affairs estimates that it will cost more than £80 billion.[135]

Timeline to opening

HS2 Ltd suggested[136] that, following ministerial approval, public consultation, parliamentary approval through a hybrid bill, and detailed design, construction of the London-Birmingham section could begin in mid-2018. This is estimated to require six-and-a-half years, with a further year to finish testing.[137] Reconstruction of Euston station and preparation of related infrastructure is expected to require the full duration of the construction period to complete. Other major construction elements include the Old Oak Common and Birmingham stations (over four years), and the tunnelling work (Old Oak to Euston, Little Missenden, Ufton Wood, Chalfont and Amersham), all estimated to require over four years for construction.[138] Opening would be at the end of 2025.[137]

The command paper suggested that opening to Birmingham should be possible by the end of 2026.[139] The timetable included the additional work of preparing the routes to Leeds and Manchester, for approval by Parliament in the hybrid bill. The initial Y-shaped network was to be presented in one bill to simplify planning and minimise the parliamentary time required for the bill.[140]

Perspectives

New political and financial dynamics

Until the start of the Great Recession, high-speed rail did not feature high among the priorities of British policy makers and institutional investors: “Britain’s best rail transportation network, the High-Speed 1 line (HS1 or ‘Channel Tunnel Rail Link’) connecting the country to Paris, [is] a strategic infrastructure asset designed by French engineers, and owned and operated by Canadian pension funds.” [141] But policy attitudes towards modern transport infrastructure started to change in the early 2010s, notably with renewed interest for the notion of UK pension investment in domestic infrastructure projects jointly with the state [142]

Government rationale

A 2008 paper, 'Delivering a Sustainable Transport System'[143] identified fourteen strategic national transport corridors in England, and described the London – West Midlands – North West England route as the "single most important and heavily used" and also as the one which presented "both the greatest challenges in terms of future capacity and the greatest opportunities to promote a shift of passenger and freight traffic from road to rail".[144] They noted that railway passenger numbers had been growing significantly in recent years[145] and that the Rugby – Euston section was already operating at up to 80% of capacity in the 2009 morning peak,[146] also that the DfT expected the WCML to have insufficient capacity south of Rugby some time around 2025.[147] This is despite the major WCML upgrade, which was completed in 2008, lengthened trains and an assumption that plans to upgrade the route with cab signalling would be realised.[148]

According to the DfT, the primary purpose of HS2 is to provide additional capacity on the rail network from London to the Midlands and North.[149] It says the new line "would improve rail services from London to cities in the North of England and Scotland,[150] and that the chosen route to the west of London will improve passenger transport links to Heathrow Airport".[151] Additionally, if the new line were connected to the Great Western Main Line (GWML) and Crossrail, it would provide links with East and West London, and the Thames Valley.[152]

In launching the project, the DfT announced that HS2 between London and the West Midlands would follow a different alignment from the WCML, rejecting the option of further upgrading or building new tracks alongside the WCML as being too costly and disruptive, and because the Victorian-era WCML alignment was not suitable for very high speeds.[153]

The Government expects that over the next 30 years, HS2 will cost £32 billion to build, provide £43.7 billion of economic benefits and generate £27 billion in fares.[154]

Support

Organisations that support the HS2 project include:

- The three major UK political parties: Conservative,[155] Labour (albeit with some criticism of the proposed route)[156] and the Liberal Democrats.[157]

- Greengauge 21, a not-for-profit research company which focuses on investigating high-speed rail technology,[158]

- The Campaign for HSR,[159] a campaign group led by Professor David Begg which aims to canvas support from businesses across the UK to promote the case for proposed high-speed rail. The campaign currently has support from over 400 UK businesses.

- HSR:UK, a group of city councils: Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham, and Sheffield.[160]

- Go-HS2,[161] a group comprising Centro, Birmingham City Council, Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, Birmingham Airport and the NEC Group. The objective of the group is to promote the benefits that its members believe HS2 will bring to Birmingham and the West Midlands.

- The Passenger Transport Executives Group (PTEG), which represents six Passenger Transport Executives.[162]

- The Scottish Government, which is generally supportive of the HS2 project and has been engaged in discussions with the UK Government about the development of a Scottish high-speed railway connecting to London and continental Europe, with the aim of reducing journey times to London from Scotland to under 3 hours.[163]

- The North East Chamber of Commerce and the Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce. Support has been confirmed by local authorities in the North of England such as Manchester and Leeds City Councils[164]

- Hammersmith and Fulham Council, which reaffirmed its support for the project in January 2012. The council's cabinet member for strategy was reported as saying "HS2 is the fastest way to deliver much-needed new homes, jobs and opportunities in one of London's poorest areas."[165]

Opposition

High Speed 2 is opposed by:

- The 51m group, which consists of 19 local authorities along or adjacent to the route. It suggests the project will cost each Parliamentary Constituency £51 million.[166] Constituent members of 51m include Buckinghamshire County Council,[167] London Borough of Hillingdon,[168] Warwickshire County Council,[169] Leicestershire County Council,[170] Oxfordshire County Council,[171] Coventry City Council[172] and Camden Borough Council.[173] The other councils that have declared their opposition are Northamptonshire[174] and Staffordshire[175] County Councils.

- The HS2 Action Alliance,[178] an umbrella group for opposition groups[179] including ad hoc entities, residents' associations, and parish councils.[180] The Alliance's primary aim is to prevent HS2 from happening; secondary aims include evaluating and minimising the impacts of HS2 on individuals, communities and the environment, and communication of facts about HS2, and its compensation scheme.[178] Even after the latest changes made to the scheme to mitigate concerns, it continues to be opposed by some MPs and personalities on the line of route.[181] A member of the 'HS2 Action Alliance' has criticised the Department of Transport's demand forecasts as being too high, as well as having other shortcomings in the assessment methodology.[182][183]

- The UK Independence Party (UKIP), which is fully opposed nationally and locally to the proposed HS2 plans. UKIP says there is no business case, no environment case and no money to pay for it.[184] UKIP has been campaigning against HS2 as it is also part of the EU's Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) Policy. It had previously proposed a much larger and more expensive three-line high-speed network running from London to Newcastle (and on to Scotland), London to Bristol (and on to Wales) and London to Birmingham along with upgrading several other sections of the WCML and Scottish rail to high speed in its 2010 manifesto.[185]

- The Green Party, which voted to oppose the HS2 plans at its Spring 2011 conference on environmental and economic grounds.[186] Alan Francis, the party transport spokesperson, had previously outlined its support for high-speed rail in principle in terms of benefits to capacity, reduced journey times and reduced carbon emissions, but recommended a line restricted to 300 to 320 kilometres per hour (190 to 200 mph) which would enable it to use existing transport corridors to a greater extent and increase efficiency.[187]

- The New Economics Foundation, a think-tank promoting environmentalism, localism and anti-capitalism. It published a formal response to the public consultation on 5 August 2011[188] which concluded that the case for a high-speed rail link was incomplete and that the benefits of the scheme had been "over-emphasised" by its promoters.[184]

- The Taxpayers Alliance, an anti-tax pressure group, which describes the project as a white elephant.[189][190]

- The Independent newspaper, which considers the costs excessive and the benefits uncertain.[191] An investigation published on 3 February 2013 claimed that 350 wildlife sites would be destroyed by the new HS2 line[192] and an accompanying editorial argued that environmentalists should oppose the project.[193] A separate investigation published on 10 March 2013 suggests that the project was unlikely to keep within its £33bn budget.[194]

- Lord Mandelson, a supporter of HS2 when in office, admitted in July 2013 that the cost estimates were "almost entirely speculative" and said the Labour Government had only proposed it to "paint an upbeat view of the future" during the financial crash.[195]

- Alistar Darling, former Labour chancellor and transport secretary, withdrew support for the project, stating to go ahead would be "foolish".[196]

- Boris Johnson, Mayor of London, and who has a large house just 10m from the new track, has repeatedly criticised the project, and stated that the costs would spiral over £70 billion.[197][198]

Other

Organisations with noncommittal, ambiguous or dissatisfied positions include:

- The Right Lines Charter, an umbrella group established in 2011 for several environmental and other organisations that support the principle of a high-speed rail network but believe that the current HS2 scheme is unsound. Members include the Campaign for Better Transport,[199] the Campaign to Protect Rural England, Friends of the Earth,[200] Greenpeace, and Railfuture.[201]

- Arup, which did the engineering work to identify routes for HS2 Ltd., has opposed the chosen route for HS2 (route 3) calling it "deeply flawed"[202] It says the route should link to Heathrow and then follow the M40 motorway and Chiltern railway line, improving the business case, lowering construction costs and creating less impact on the countryside.[203]

- Railfuture, a railway campaigning organisation, which supports high-speed rail in principle, but stated in its submission to the Transport Select Committee Inquiry that it sees no benefit in trains running at up to 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph) and therefore is not in favour of the current proposal and route, and suggests that alternatives be investigated.[204]

- The Campaign to Protect Rural England,[205] which believes that lower speeds would increase journey times only slightly, while allowing the line to run along existing motorway and railway corridors, reducing intrusion.[205]

- The Woodland Trust opposes the current route of the proposed High Speed 2 rail link because of its impact on ancient woodland. It reports that 33 ancient woods – areas continuously wooded since 1600 – face destruction, with 34 more indirectly at risk from disturbance, noise and pollution.[206]

- The Wildlife Trusts, which have criticised the proposals, stating that the former Government's policy on High Speed Rail (March 2010) underestimated the effect on wildlife habitats (with 4 SSSIs and over 50 of other types of nature site affected), as well as noting that the proposals had not comprehensively shown any significant effect on transport carbon emissions and questioning the economic benefits of a line. The trusts called for additional research to be done on the effects of a high-speed line.[207]

- The Federation of Small Businesses, which has expressed scepticism over the need for high-speed rail, stating that roads expenditure was more useful for its members.[208]

- The Coventry and Warwickshire Chamber of Commerce, which opined that HS2 offered no benefit to its area.[209]

- Derby City Council was disappointed at the chosen location for the East Midlands Hub station in Toton, preferring a route that would make use of the existing Derby railway station.[210] These plans are opposed by Derbyshire County Council,[211] Nottingham City Council,[212] and Rushcliffe Borough Council.[213]

- The Commons Transport Committee, which in November 2011 reported that the scheme had "a good case" and offered "a new era of inter-urban travel in Britain."[215] However, it also said there should be a firm commitment made now to extend the line to Manchester and Leeds and that other investment in rail should not suffer, and noted a poor level of public debate which had failed to address the facts and had resorted to name-calling and accusations of nimbyism.[216] While questioning some data, it found a good economic case for the project bringing more benefits than a conventional rail line, that the noise impact would be less than feared and that while it would not reduce carbon dioxide emissions they would be smaller than under further motorway or air traffic expansion and that the business case for diverting via Heathrow had not been made. The report's findings were welcomed by the Association of Train Operating Companies, the Campaign for Better Transport, the Countryside Alliance and the Campaign to Protect Rural England. Action Groups Against High Speed Two (AGHAST) condemned the authors as a 'partisan committee' though they welcomed some of the findings, saying it poked holes in the Government's arguments.

Hybrid bill

To implement the HS2 proposals the government will introduce on behalf of HS2 Ltd two hybrid bills, one for each phase, as the railway will impact on private individuals and organisations along the route or elsewhere. Each bill is required to address the environmental impact and how this will be mitigated, and to allow individuals affected to petition parliament to seek amendments or assurances.[32] The timeline requires for the legislation relating to the construction and operation of phase 1 to be introduced to parliament towards the end of 2013 and to pass into law by the spring of 2015. Parliament's second reading of the hybrid bill for phase 1 took place on 28 April 2014 and was approved by 452 votes to 41.[217] The hybrid bill for phase 2 will be prepared for January 2015.[218]

A legal requirement of the hybrid bill is the production and deposition of an Environmental impact assessment (EIA) to identify the significant impacts on the community, property, landscape, visual amenity, biodiversity, surface and ground water, archaeology, traffic, transport, waste and resources. Proposals to avoid, reduce or remedy significant adverse impacts through mitigation measures are also required. HS2 Ltd announced its intention to consult on the 'scope and methodology' of the EIA in April 2012 and based on this will publish a draft environmental statement on which it intends to consult with national bodies and local authorities and community forums along the route, in the spring of 2013.[219]

Preparation bill

The High Speed Rail (Preparation) Bill was passed by 350 votes to 34 in the House of Commons on 31 October 2013. The bill will undergo further scrutiny in the House of Lords. This legislation releases funds to pay for surveys, buy property and compensate evicted residents.[220]

Community engagement

HS2 Ltd announced in March 2012 that it will conduct consultations with local people and organisations along the London to West Midlands route through community forums, planning forums and an environment forum. Between them the forums will discuss the development of the route, the identification of potential impacts and look at the best approaches to mitigate these.[221] HS2 has also confirmed that the consultations will be conducted in line with the terms of the Aarhus Convention which commits organisations to provide access to environmental information they hold, and enable participation and challenge as part of decision making processes.[222]

Community forums

HS2 Ltd set up 25 community forums along Phase 1 in March 2012. The forums provide for representatives of local authorities, residents associations, special interest groups and environment bodies in each community forum area to 'engage' with HS2 Ltd to:- "discuss potential ways to avoid and mitigate the environmental impacts of the route, such as screening views of the railway; managing noise and reinstating highways; highlight local priorities for the route design; identify possible community benefits."[223] Forum meetings will take place every 2–3 months and will have an independent chairman appointed by HS2.

Planning forums

Six planning forums aligned to local council boundaries along Phase 1 of the route were announced by HS2 in April 2012. Membership would comprise HS2 Ltd and officers from highway and planning authorities. Meeting every two months, their particular focus would include, location specific constraints, design and impacts, including construction; spatial planning considerations; the planning regime to be set out in the hybrid bill; and proposals for mitigations.[224]

Environment forum

An environment forum involving HS2 Ltd and national representatives of environmental organisations and government departments has been formed to assist with the development of the HS2 environmental policy.[225]

Environmental and community impact

Land value

Currently the impact of HS2 is land value – values of homes close to the route have already fallen, by as much as 40 per cent,[135] and despite expectations that property prices would increase close to proposed stations on the route, evidence suggests this has not happened although the government has pointed to the number of businesses relocating their headquarters from London to Birmingham as having a positive impact on property prices.[226]

Visual impact

The visual impact of HS2 has received particular attention in the Chilterns, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[228] The Government announced in January 2011 that 2m trees would be planted along sections of the route to mitigate the visual impact.[229]

Property demolition and land take

Phase 1 would result in the demolition of more than 400 houses; 250 around Euston station, 20–30 between Old Oak Common and West Ruislip, a number in Ealing, around 50 in Birmingham, and the remainder in pockets along the route.[230] This includes nine Grade II listed buildings and possibly a Grade II* listed farmhouse at Hampton in Arden. It is unknown if the historic building will be moved, and owners get more compensation that lower value of house.[231]

Near Nottingham, Trent Cottages, a row of railway workers housing built in the 1860s would also have to be demolished.[232]

In Birmingham, the new Curzon Gate student residence would have to be demolished[233] and Birmingham City University wanted a £30 million refund after the plans were revealed.[100]

Ancient Woodland impact

High Speed Rail: woods, trees and wildlife published by Woodland Trust explains that 33 ancient woods may be bisected or reduced in area due to HS2, with 34 more near enough to suffer secondary effects from disturbance, noise and pollution. Ancient woods are areas that have been continuously wooded since at least 1600 and are our richest land-based habitat. These ancient woods under threat have had relatively little disturbance over centuries and have therefore developed complex and diverse ecological communities of plants and animals. Only 2% of the UK is covered in ancient woodland and ancient woods are home to 256 species of conservation concern.[234]

Loss of wildlife habitat, and recreation space

David Lidington, MP for Aylesbury, raised concerns that the route could damage the 47 kilometres (29 mi)-wide Chiltern Hills area of outstanding natural beauty, the Colne Valley regional park on the outskirts of London, and other areas of green belt.[235]

The route passes through the Chilterns in Buckinghamshire via the Misbourne Valley. Initially through a tunnel beneath Chalfont St Giles[236] emerging just after Amersham, then past Wendover and Stoke Mandeville.[237] Its proposals include a re-alignment of more than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) of the River Tame, and construction of a 0.63 kilometres (0.39 mi) long viaduct and a cutting[238] through ancient woodland at a nature reserve at Park Hall on the edge of Birmingham.[239]

Carbon emissions

In 2007 the DfT commissioned a report, Estimated Carbon Impact of a New North South Line, from Booz Allen Hamilton to investigate the likely overall carbon impact associated with the construction and operation of a new rail line to either Manchester or Scotland including the extent of carbon reduction or increase from population shift to rail use, and the comparison with the case in which no new high-speed lines were built.[240] The report concluded that there was no net carbon benefit in the foreseeable future taking only the route to Manchester. Additional carbon from building a new rail route would be larger in the first ten years at least than a model were no new rail line was built.[241]

The High Speed Rail Command paper published in March 2010 stated that the project was likely to be roughly carbon neutral.[242]

The Eddington Report cautioned against the common argument of modal shift from aviation to high-speed rail as a carbon-emissions benefit, since only 1.2% of UK carbon emissions are due to domestic commercial aviation, and since rail transport energy efficiency is reduced as speed increases.[243]

The Government White Paper Delivering a Sustainable Railway states trains that travel at a speed of 350 kilometres per hour (220 mph) currently use 90% more energy than at 200 kilometres per hour (125 mph); which results in carbon emissions for a London to Edinburgh journey of approximately 14 kilograms (31 lb) per passenger for high-speed rail compared to 7 kilograms (15 lb) per passenger for conventional rail. Air travel uses 26 kilograms (57 lb) per passenger for the same journey. The paper questioned the value for money of high-speed rail as a method of reducing carbon emissions, but noted that with a switch to carbon-free or neutral energy production the case becomes much more favourable.[244]

The House of Commons Transport Select Committee Report in November 2011 (paragraph 77) concluded that the Government's claim that HS2 would have substantial carbon reduction benefits did not stand up to scrutiny. At best, the Select Committee found, HS2 could make a small contribution to the Government's carbon-reduction targets. However this was dependent on the government making rapid progress on reducing carbon emissions from UK electricity generation.[32]

Noise

HS2 Ltd stated that 21,300 dwellings could experience a noticeable increase in rail noise and 200 non-residential receptors (community, education, healthcare, and recreational/social facilities) within 300 metres (980 ft) of the preferred route have the potential to experience significant noise impacts.[230] The Government has announced that trees planted to create a visual barrier will reduce noise pollution.[229]

Geology and water supply

Research presented by Dr Haydon Bailey, geological adviser to the Chiltern Society, showed that HS2 tunnelling could cause long-term damage to the chalk aquifer system responsible for water supply for the North Western Home Counties and North London.[245]

Compensation

From the beginning of the HS2 consultation period, the government has factored in several plans to compensate people who will or may be affected. Once original plans had been released in 2010, the Exceptional Hardship Scheme (EHS) was set up, however this was at the government's discretion and Phase 1 came to an end on 17 June 2010. With EHS Phase 2 running throughout 2013. Both EHS are intended to compensate homeowners who have difficulty selling their home because of the HS2 route announcement, to protecting those whose property value may be seriously affected by the 'preferred route option' and who urgently need to sell.[246]

Exceptional Hardship Scheme criteria

With Phase 1 applications intended to run from about August 2010 until the route was chosen in 2012 and Phase 2 throughout 2013; homeowners are/were advised to apply to the Secretary of State to buy their home, as long as all of the following criteria are met:

- Residential owner-occupier.

- Pressing need to sell. This means a change in employment location, extreme financial pressure, to accommodate enlarged family, move into sheltered accommodation, or medical condition of a family member.

- On or in 'close vicinity' of the 'preferred route' (that is mainly those who will later on be covered by statutory blight provisions).

- Have tried to sell – been on the market for at least three months with no offers within 15% of full market value (as if no HS2).

- Can demonstrate inability to sell is due to HS2.

- No knowledge of HS2 before acquiring the property.

Decisions on individual applications will by made by a panel of experts.[247]

Public consultations

Since the announcement of Phase 1 the government has had plans to create an overall 'Y shaped' line with termini in Manchester and Leeds. Since the intentions to further extend were announced an additional compensation scheme was set up.[248] Consultations with those affected were set up over late 2012 and January 2013, to allow homeowners to express their concerns within their local community.[249]

The results of the consultations are not yet known, but Alison Munro, chief executive of HS2 Ltd, has stated that it is also looking at other options, including property bonds.[250] The statutory blight regime would apply to any route confirmed for a new high-speed line following the public consultations, which took place between 2011 and January 2013.[251][249]

The government has said it plans to introduce a new discretionary hardship scheme to ensure the housing market along the route is not unduly disrupted.

HS2 Action Alliance's alternative compensation solution for property blight was presented to DfT/HS2 Ltd and Secretary of State for Transport Philip Hammond, in response to the consultation on the EHS. The Alliance also presented DfT and HS2 Ltd with a pilot study on property blight.[252]

Alternative plans

Upgrade existing lines

A Department for Transport-commissioned study into alternatives identified the following options:

- lengthen existing trains and platforms, cost £3.5bn

- remodel infrastructure to increase service frequency, cost £13bn

- increase capacity and reduce journey times by bypassing slow track sections, cost £24bn

According to Network Rail, these options would cause massive disruption to passengers for limited improvement.[253]

Great Central option

Kelvin Hopkins MP, together with some hauliers and supermarket groups, has drawn up plans to reopen the former Great Central Main Line as an alternative to HS2.[254][255] The cost of the Great Central option has been estimated by supporters at £6 billion, compared with £42.6 billion for HS2.[256] A previous attempt to re-open the Great Central as an intermodal freight transport railway under the name Central Railway was made in about 1990. Much of the former Great Central railway alignment has been built on where it passes through towns and cities, so any reopening would require extensive demolition.

Incorporating HS2 and HS3