Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt

The Egyptian hieroglyphics text Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt is one of the modern primers on the Egyptian language hieroglyphs, from the late 20th to early 21st century. The text is authored by Maria Carmela Betrò, c. 1995, (English 1996).[1]

The standard version of analytic Egyptian hieroglyphs is based upon the 26 categories of the Gardiner's Sign List, (about 700 signs). That categorization is still the basic standard. The approach in Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt is to use some of the Gardiner sign categories, to focus on specific major-use signs. The end of a thematic chapter then has synoptic write-ups for additional lesser used signs, or a sign from another category that is 'related'. it is related to the ancient Egypt

Betrò's book has the following standard categories, as chapters:

- Mankind

- Gods

- Animals

- Trees and Plants

- Sky, Earth, Water

- The House

- The City, Palace, and Temples

- Arts and Religion

As can be seen the 26 categories of Gardiner's Sign List has been reduced to 7. There is no specific category for the Unclassified signs, Signs from Demotic, or the problematic signs.

With the older styles and outlines of hieroglyphs being redone and rethought by modern Egytologists, new approaches to books on the Egyptian language and the hieroglyphs have been tried.

Origins of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

The ancient Egyptians believed that writing was invented by the god Thoth and called their hieroglyphic script "mdwt ntr" (god's words). The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek hieros (sacred) plus glypho (inscriptions) and was first used by Clement of Alexandria.

The earliest known examples of writing in Egypt have been dated to 3,400 BC. The latest dated inscription in hieroglyphs was made on the gate post of a temple at Philae in 396 AD.

The hieroglyphic script was used mainly for formal inscriptions on the walls of temples and tombs. In some inscriptions the glyphs are very detailed and in full colour, in others they are simple outlines. For everyday writing the hieratic script was used.

After the Emperor Theodsius I ordered the closure of all pagan temples throughout the Roman empire in the late 4th century AD, knowledge of the hieroglyphic script was lost. decipher the script.

Decipherment Many people have attempted to decipher the Egyptian scripts since the 5th century AD, when Horapollo provided explanations of nearly two hundred glyphs, some of which were correct. Other decipherment attempts were made in the 9th and 10th by Arab historians Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya, and in the 17th century by Athanasius Kircher. These attempts were all based on the mistaken assumption that the hieroglyphs represented ideas and not sounds of a particular language.

The discovery, in 1799, of the Rosetta Stone, a bilingual text in Greek and the Egyptian Hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts enabled scholars such as Silvestre de Sacy, Johan David Åkerblad and Thomas Young to make real progress with their decipherment efforts, and by the 1820s Jean-François Champollion had made the complete decipherment of the Hieroglyphic script. He reaslised that the Coptic language, a descendent of Ancient Egyptian used as a liturgical language in the Coptic Church in Egypt, could be used to help understand the language of the hieroglyphic inscriptions.

Notable features Possibly pre-dates Sumerian Cuneiform writing - if this is true, the Ancient Egyptian script is the oldest known writing system. Another possibility is that the two scripts developed at more or less the same time. The direction of writing in the hieroglyphic script varied - it could be written in horizontal lines running either from left to right or from right to left, or in vertical columns running from top to bottom. You can tell the direction of any piece of writing by looking at the way the animals and people are facing - they look towards the beginning of the line. The arrangement of glyphs was based partly on artistic considerations. A fairly consistent core of 700 glyphs was used to write Classical or Middle Egyptian (ca. 2000-1650 BC), though during the Greco-Roman eras (332 BC - ca. 400 AD) over 5,000 glyphs were in use. The glyphs have both semantic and phonetic values. For example, the glyph for crocodile is a picture of a crocodile and also represents the sound "msh". When writing the word for crocodile, the Ancient Egyptians combined a picture of a crocodile with the glyphs which spell out "msh". Similarly the hieroglyphs for cat, miw, combine the glyphs for m, i and w with a picture of a cat.

By combining the following glyphs, any number could be constructed. The higher value signs were always written in front of the lower value ones.

Numerals

Sample texts Sample text in Ancient Egyptian

Transliteration: iw wnm msh nsw, this means "The crocodile eats the king".

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Translation All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Text specifics

The text starts with a history, and The Origins; also The Gardiner List, Chronological Table, and the The Principles of Hieroglyphic Writing.[2]

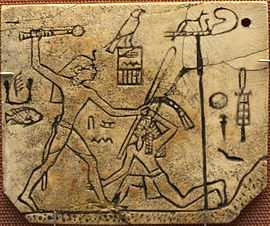

The Origins section contains photos of the Libyan Palette, sides A, B; also the Narmer Palette, sides A, B, and the "Four Dogs Palette" at the Louvre. The Min Palette is also referenced in the text pages, as well as items specific to the cosmetic palettes of Ancient Egypt. It also explains the Old Kingdom label (Ancient Egypt), (for Pharaoh Den), with some of the oldest used hieroglyph sign examples, and also discusses the signs upon pottery.

The English text is 251 pages, and contains a short word glossary for 29 entries, a one-page bibliography, and a five-page index.[3]

The Gardiner sign list covers five pages,[4] with the 650+ signs, with hieroglyph topic pages in the red color for the glyph and a page number-adjacent, as a location .

References

- Betrò, Maria Carmela. Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt, c. 1995, 1996-(English), Abbeville Press Publishers, New York, London, Paris (hardcover, ISBN 0-7892-0232-8)