Heun's method

In mathematics and computational science, Heun's method may refer to the improved[1] or modified Euler's method (that is, the explicit trapezoidal rule[2]), or a similar two-stage Runge–Kutta method. It is named after Karl Heun and is a numerical procedure for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with a given initial value. Both variants can be seen as extensions of the Euler method into two-stage second-order Runge–Kutta methods.

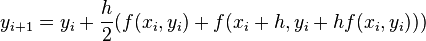

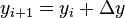

The procedure for calculating the numerical solution to the initial value problem via the improved Euler's method is:

by way of Heun's method, is to first calculate the intermediate value  and then the final approximation

and then the final approximation  at the next integration point.

at the next integration point.

where  is the step size and

is the step size and  .

.

Description

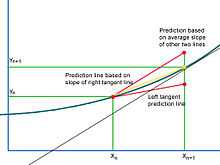

Euler’s method is used as the foundation for Heun’s method. Euler's method uses the line tangent to the function at the beginning of the interval as an estimate of the slope of the function over the interval, assuming that if the step size is small, the error will be small. However, even when extremely small step sizes are used, over a large number of steps the error starts to accumulate and the estimate diverges from the actual functional value.

Where the solution curve is concave up, its tangent line will underestimate the vertical coordinate of the next point and vice versa for a concave down solution. The ideal prediction line would hit the curve at its next predicted point. In reality, there is no way to know whether the solution is concave-up or concave-down, and hence if the next predicted point will overestimate or underestimate its vertical value. The concavity of the curve cannot be guaranteed to remain consistent either and the prediction may overestimate and underestimate at different points in the domain of the solution. Heun’s Method addresses this problem by considering the interval spanned by the tangent line segment as a whole. Taking a concave-up example, the left tangent prediction line underestimates the slope of the curve for the entire width of the interval from the current point to the next predicted point. If the tangent line at the right end point is considered (which can be estimated using Euler’s Method), it has the opposite problem [3] The points along the tangent line of the left end point have vertical coordinates which all underestimate those that lie on the solution curve, including the right end point of the interval under consideration. The solution is to make the slope greater by some amount. Heun’s Method considers the tangent lines to the solution curve at both ends of the interval, one which overestimates, and one which underestimates the ideal vertical coordinates. A prediction line must be constructed based on the right end point tangent’s slope alone, approximated using Euler's Method. If this slope is passed through the left end point of the interval, the result is evidently too steep to be used as an ideal prediction line and overestimates the ideal point. Therefore, the ideal point lies approximately half way between the erroneous overestimation and underestimation, the average of the two slopes.

Euler’s Method is used to roughly estimate the coordinates of the next point in the solution, and with this knowledge, the original estimate is re-predicted or corrected.[4] Assuming that the quantity  on the right hand side of the equation can be thought of as the slope of the solution sought at any point

on the right hand side of the equation can be thought of as the slope of the solution sought at any point  , this can be combined with the Euler estimate of the next point to give the slope of the tangent line at the right end-point. Next the average of both slopes is used to find the corrected coordinates of the right end interval.

, this can be combined with the Euler estimate of the next point to give the slope of the tangent line at the right end-point. Next the average of both slopes is used to find the corrected coordinates of the right end interval.

Derivation

Using the principle that the slope of a line equates to the rise/run, the coordinates at the end of the interval can be found using the following formula:

,

,

The accuracy of the Euler method improves only linearly with the step size is decreased, whereas the Heun Method improves accuracy quadratically

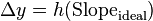

.[5] The scheme can be compared with the implicit trapezoidal method, but with  replaced by

replaced by  in order to make it explicit.

in order to make it explicit.  is the result of one step of Euler's method on the same initial value problem. So, Heun's method is a predictor-corrector method with forward Euler's method as predictor and trapezoidal method as corrector.

is the result of one step of Euler's method on the same initial value problem. So, Heun's method is a predictor-corrector method with forward Euler's method as predictor and trapezoidal method as corrector.

Runge–Kutta method

The improved Euler's method is a two-stage Runge–Kutta method, and can be written using the Butcher tableau (after John C. Butcher):

| 0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1/2 | 1/2 |

The other method referred to as Heun's method (also known as Ralston's method) has the Butcher table:[6]

| 0 | |||

| 2/3 | 2/3 | ||

| 1/4 | 3/4 |

This method minimizes the truncation error.

References

- ↑ Süli, Endre; Mayers, David (2003), An Introduction to Numerical Analysis, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-00794-1.

- ↑ Ascher, Uri M.; Petzold, Linda R. (1998), Computer Methods for Ordinary Differential Equations and Differential-Algebraic Equations, Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-89871-412-8.

- ↑ "Numerical Methods for Solving Differential Equations". San Joaquin Delta College. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12.

- ↑ Chen, Wenfang.; Kee, Daniel D. (2003), Advanced Mathematics for Engineering and Science, MA, USA: World Scientific, ISBN 981-238-292-5.

- ↑ "The Euler-Heun Method". LiveToad.org.

- ↑ Leader, Jeffery J. (2004), Numerical Analysis and Scientific Computation, Boston: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-73499-0.

| |||||||||||||

![y_{i+1} = y_i + \frac{h}{2}[f(t_i, y_i) + f(t_{i+1},\tilde{y}_{i+1})],](../I/m/1893fee94201b9cb5e5a0ff7e2f37d7b.png)