Hermite distribution

|

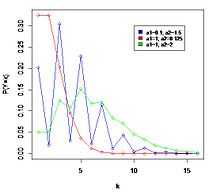

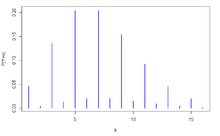

Probability mass function  The horizontal axis is the index k, the number of occurrences. The function is only defined at integer values of k. The connecting lines are only guides for the eye. | |

|

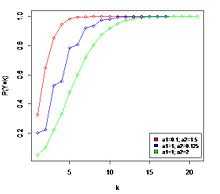

Cumulative distribution function  The horizontal axis is the index k, the number of occurrences. The CDF is discontinuous at the integers of k and flat everywhere else because a variable that is Hermite distributed only takes on integer values. | |

| Notation |

|

|---|---|

| Parameters | a1 ≥ 0, a2 ≥ 0 |

| Support | k ∈ { 0, 1, 2, ... } |

| pmf |

![e^{[-(a_1+a_2)]} \sum_{j=0}^{[n/2]} \frac{a_1^{n-2j}a_2^j}{(n-2j!)j!}](../I/m/571d3e1e5339de0345b331188a963327.png) |

| CDF |

![e^{[-a_1+a_2]} \sum_{i=0}^{\lfloor x\rfloor} \sum_{j=0}^{[i/2]} \frac{a_1^{i-2j}a_2^j}{(i-2j)!j!}](../I/m/027629b8ecada8b9afd873ddf5d91d0b.png) |

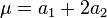

| Mean |

|

| Variance |

|

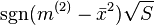

| Skewness |

|

| Ex. kurtosis |

|

| MGF |

|

| CF |

|

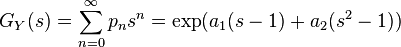

| PGF |

|

In probability theory and statistics, the Hermite distribution, named after Charles Hermite, is a discrete probability distribution used to model count data with more than one parameter. This distribution is flexible in terms of its ability to allow a moderate over-dispersion in the data. The Hermite distribution is a special case of the Poisson binomial distribution, when n = 2.

The authors Kemp and Kemp [1] have called it "Hermite distribution" from the fact its probability function and the moment generating function can be expressed in terms of the coefficients of (modified) Hermite polynomials.

History

The distribution first appeared in the paper Applications of Mathematics to Medical Problems,[2] by Anderson Gray McKendrick in 1926. In this work the author explains several mathematical methods that can be applied to medical research. In one of this methods he considered the bivariate Poisson distribution and showed that the distribution of the sum of two correlated Poisson variables follow a distribution that later would be known as Hermite distribution.

As a practical application, McKendrick considered the distribution of counts of bacteria in leucocytes. Using the method of moments he fitted the data with the Hermite distribution and found the model more satisfactory than fitting it with a Poisson distribution.

The distribution was formally introduced and published by C. D. Kemp and Adrienne W.Kemp in 1965 in their work Some Properties of ‘Hermite’ Distribution. The work is focused on the properties of this distribution for instance a necessary condition on the parameters and their Maximum Likelihood (MLE), the analysis of the probability generating function (PGF) and how it can be expressed in terms of the coefficients of (modified) Hermite polynomials. An example they have used in this publication is the distribution of counts of bacteria in leucocytes that used McKendrick but Kemp and Kemp estimate the model using the maximum likelihood method.

Hermite distribution is is a special case of discrete compound Poisson distribution with only 2 parameters. [3] [4]

The same authors published in 1966 the paper An alternative Derivation of the Hermite Distribution.[5] In this work established that the Hermite distribution can be obtained formally by combining a Poisson distribution with a Normal distribution.

In 1971, Y. C. Patel[6] did a comparative study of various estimation procedures for the Hermite distribution in his doctoral thesis. It included maximum likelihood, moment estimators, mean and zero frequency estimators and the method of even points.

In 1974, Gupta and Jain[7] did a research on a generalized form of Hermite distribution.

In the probabilistic number theory, due to Bekelis's work,[8] when a strongly additive function  only takes value {0,1,2} on prime number p, under some conditions, then the frequent number of

only takes value {0,1,2} on prime number p, under some conditions, then the frequent number of  convergent to a Hermite distribution for

convergent to a Hermite distribution for  .[9]

.[9]

Definition

Probability mass function

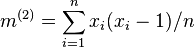

Let X1 and X2 be two independent Poisson variables with parameters a1 and a2. The probability distribution of the random variable Y = X1 + 2X2 is the Hermite distribution with parameters a1 and a2 and probability mass function is given by [10]

where

- n = 0, 1, 2, ...

- a1, a2 ≥ 0.

- (n − 2j)! and j! are the factorial of (n − 2j) and j, respectively.

- [n/2] is the integer part of [n/2].

As a special case of discrete compound Poisson, there are at least ten approaches to proving the probability mass function of Hermite distribution.[9]

The probability generating function of the probability mass is,[10]

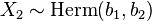

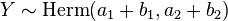

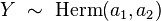

Notation

When a random variable Y = X1 + 2X2 is distributed by an Hermite distribution, where X1 and X2 are two independent Poisson variables with parameters a1 and a2, we write

Properties

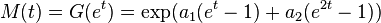

Moment and cumulant generating functions

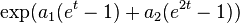

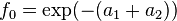

The moment generating function of a random variable X is defined as the expected value of et, as a function of the real parameter t. For an Hermite distribution with parameters X1 and X2, the moment generating function exists and is equal to

The cumulant generating function is the logarithm of the moment generating function and is equal to [4]

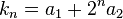

If we consider the coefficient of (it)rr! in the expansion of K(t) we obtain the r-cumulant

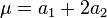

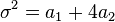

Hence the mean and the succeeding three moments abouit it are

| Order | Moment | Cumulant |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |  |

| 2 |  |  |

| 3 |  |  |

| 4 |  |  |

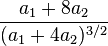

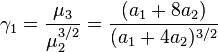

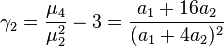

Skewness

The skewness is the third moment centered around the mean divided by the 3/2 power of the standard deviation, and for the hermite distribution is,[4]

- Always

, so the mass of the distribution is concentrated on the left.

, so the mass of the distribution is concentrated on the left.

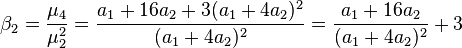

Kurtosis

The kurtosis is the fourth moment centered around the mean, divided by the square of the variance, and for the Hermite distribution is,[4]

The excess kurtosis is just a correction to make the kurtosis of the normal distribution equal to zero, and it is the following,

- Always

, or

, or  the distribution has a high acute peak around the mean and fatter tails.

the distribution has a high acute peak around the mean and fatter tails.

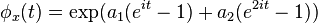

Characteristic function

In a discrete distribution the characteristic function of any real-valued random variable is defined as the expected value of  , where i is the imaginary unit and t ∈ R

, where i is the imaginary unit and t ∈ R

This function is related to the moment-generating function via  . Hence for this distribution the characteristic function is,[1]

. Hence for this distribution the characteristic function is,[1]

Cumulative distribution function

The cumulative distribution function is,[1]

Other properties

- This distribution can have any number of modes. As an example, the fitted distribution for McKendrick’s [2] data has an estimated parameters of

,

,  . Therefore, the first five estimated probabilities are 0.899, 0.012, 0.084, 0.001, 0.004.

. Therefore, the first five estimated probabilities are 0.899, 0.012, 0.084, 0.001, 0.004.

- This distribution is closed under addition or closed under convolutions.[11] As the Poisson distribution, the Hermite distribution has this property. Given 2 random Hermite variables

and

and  , then Y = X1 + X2 follows an Hermite distribution,

, then Y = X1 + X2 follows an Hermite distribution,  .

.

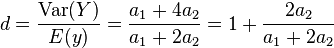

- This distribution allows a moderate overdispersion, so it can be used when data has this property.[11] A random variable has overdispersion, or it is overdispersed with respect the Poisson distribution, when its variance is greater than its expected value. The Hermite distribution allows a moderate overdispersion because the coefficient of dispersion is always between 1 and 2,

Parameter estimation

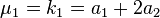

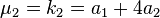

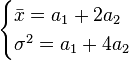

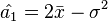

Method of moments

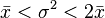

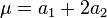

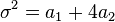

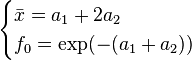

The mean and the variance of the Hermite distribution are  and

and  , respectively. So we have these two equation,

, respectively. So we have these two equation,

Solving these two equation we get the moment estimators  and

and  of a1 and a2.[6]

of a1 and a2.[6]

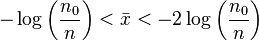

Since a1 and a2 both are positive, the estimator  and

and  are admissible (≥ 0) only if,

are admissible (≥ 0) only if,  .

.

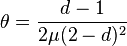

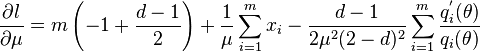

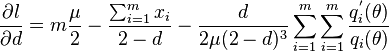

Maximum likelihood

Given a sample X1 ... Xm are independent random variables each having an Hermite distribution we wish to estimate the value of the parameters  and

and  . We know that the mean and the variance of the distribution are

. We know that the mean and the variance of the distribution are  and

and  , respectively. Using these two equation,

, respectively. Using these two equation,

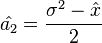

We can parameterize the probability function by μ and d

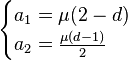

Hence the log-likelihood function is,[11]

where

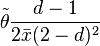

From the log-likelihood function, the likelihood equations are,[11]

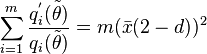

Straightforward calculations show that,[11]

-

- And d can be found by solving,

where

- It can be shown that the log-likelihood function is strictly concave in the domain of the parameters. Consequently, the MLE is unique.

The likelihood equation does not always have a solution like as it shows the following proposition,

Proposition:[11] Let X1, ..., Xm come from a generalized Hermite distribution with fixed n. Then the MLEs of the parameters are  and

and  if only if

if only if  , where

, where  indicates the empirical factorial momement of order 2.

indicates the empirical factorial momement of order 2.

- Remark 1: The condition

is equivalent to

is equivalent to  where

where  is the empirical dispersion index

is the empirical dispersion index

- Remark 2: If the condition is not satisfied, then the MLEs of the parameters are

and

and  , that is, the data are fitted using the Poisson distribution.

, that is, the data are fitted using the Poisson distribution.

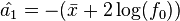

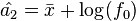

Zero frequency and the mean estimators

A usual choice for discrete distributions is the zero relative frequency of the data set which is equated to the probability of zero under the assumed distribution. Observing that  and

and  . Following the example of Y. C. Patel (1976) the resulting system of equations,

. Following the example of Y. C. Patel (1976) the resulting system of equations,

We obtain the zero frequency and the mean estimator a1 of  and a2 of

and a2 of  ,[6]

,[6]

where  , is the zero relative frequency, n > 0

, is the zero relative frequency, n > 0

It can be seen that for distributions with a high probability at 0, the efficiency is high.

- For admissible values of

and

and  , we must have

, we must have

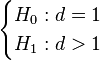

Testing Poisson assumption

When Hermite distribution is used to model a data sample is important to check if the Poisson distribution is enough to fit the data. Following the parametrized probability mass function used to calculate the maximum likelihood estimator, is important to corroborate the following hypothesis,

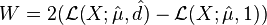

Likelihood-ratio test

The Likelihood-ratio test statistic [11] for hermite distribution is,

Where  is the log-likelihood function. As d = 1 belongs to the boundary of the domain of parameters, under the null hypothesis, W does not have an asymptotic

is the log-likelihood function. As d = 1 belongs to the boundary of the domain of parameters, under the null hypothesis, W does not have an asymptotic  distribution as expected. It can be established that the asymptotic distribution of W is a 50:50 mixture of the constant 0 and the

distribution as expected. It can be established that the asymptotic distribution of W is a 50:50 mixture of the constant 0 and the  . The α upper-tail percentage points for this mixture are the same as the 2α upper-tail percentage points for a

. The α upper-tail percentage points for this mixture are the same as the 2α upper-tail percentage points for a  ; for instance, for α=0.01,0.05, and 0.10 they are 5.41189, 2.70554 and 1.64237.

; for instance, for α=0.01,0.05, and 0.10 they are 5.41189, 2.70554 and 1.64237.

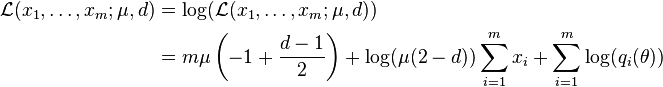

The "score" or Lagrange multiplier test

The score statistic is,[11]

where m is the number of observations.

The asymptotic distribution of the score test statistic under the null hypothesis is a  distribution. It may be convenient to use a signed version of the score test, that is,

distribution. It may be convenient to use a signed version of the score test, that is,  , following asympotically a standard normal.

, following asympotically a standard normal.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kemp, C.D; Kemp, A.W (1965). "Some Properties of the "Hermite" Distribution". Biometrika 52 (3-4): 381–394. doi:10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.381.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McKendrick, A.G. (1926). "Applications of Mathematics to Medical Problems". Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society 44: 98–130. doi:10.1017/s0013091500034428.

- ↑ Huiming, Zhang; Yunxiao Liu; Bo Li (2014). "Notes on discrete compound Poisson model with applications to risk theory". Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 59: 325–336. doi:10.1016/j.insmatheco.2014.09.012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Johnson, N.L., Kemp, A.W., and Kotz, S. (2005) Univariate Discrete Distributions, 3rd Edition, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-27246-5.

- ↑ Kemp, ADRIENNE W.; Kemp C.D (1966). "An alternative derivation of the Hermite distribution". Biometrika 53 (3-4): 627–628. doi:10.1093/biomet/53.3-4.627.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Patel, Y.C (1976). "Even Point Estimation and Moment Estimation in Hermite Distribution". Biometrics 32 (4): 865–873. doi:10.2307/2529270.

- ↑ Gupta, R.P.; Jain, G.C. (1974). "A Generalized Hermite distribution and Its Properties". SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 27: 359–363. doi:10.1137/0127027.

- ↑ Bekelis, D. (1996). "Convolutions of the Poisson laws in number theory". In Analytic & Probabilistic Methods in Number Theory: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference in Honour of J. Kubilius, Lithuania 4: 283–296.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Zhang, H.; He, J.; Huang, H. (2013). "On Nonnegative Integer-Valued Lévy Processes and Applications in Probabilistic Number Theory and Inventory Policies". American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 2: 110–121. doi:10.11648/j.ajtas.20130205.11.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kotz, Samuel (1982–1989). Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. John Wiley. ISBN 0471055522.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Puig, P. (2003). "Characterizing Additively Closed Discrete Models by a Property of Their Maximum Likelihood Estimators, with an Application to Generalized Hermite Distributions". Journal of the American Statistical Association 98: 687–692. doi:10.1198/016214503000000594.

![p_n = P(Y=n) = e^{[-a_1+a_2]} \sum_{j=0}^{[n/2]} \frac{a_1^{n-2j}a_2^j}{(n-2j)!j!}](../I/m/c78a51f24b7b1b6d224d56e96e63ce87.png)

![\phi(t)= E[e^{itX}] = \sum_{j=0}^\infty e^{ijt}P[X=j]](../I/m/951d6637a38b8bb539d20c8b8f77ae96.png)

![\begin{align}

F(x;a_1,a_2)& = P(X \leq x)\\

& = \exp (-(a_1+a_2)) \sum_{i=0}^{\lfloor x\rfloor} \sum_{j=0}^{[i/2]} \frac{a_1^{i-2j}a_2^j}{(i-2j)!j!}

\end{align}](../I/m/8c62a84656567abc864881de47ac3971.png)

![P(X=x)= \exp\left(-\left(\mu(2-d)+ \frac{\mu(d-1)}{2}\right)\right) \sum_{j=0}^{[x/2]} \frac{(\mu(2-d))^{x-2j}\left(\frac{\mu(d-1)}{2}\right)^j}{(x-2j)!j!}](../I/m/a6b2a0ec48115d25f49183cad3d1017a.png)

![q_i(\theta) = \sum_{j=0}^{[x_i/2]} \frac{\theta^j}{(x_i-2j)!j!}](../I/m/5886e05909b7643ac22c63a5bd1dfd44.png)

![S_2 = 2m \left[\frac{m^{(2)}-\bar{x}^2}{2\bar{x}}\right]^2 = \frac{m(\tilde{d}-1)^2}{2}](../I/m/7bae76174ace7ce6f710e64e4960e3d1.png)