Herbrand's theorem

Herbrand's theorem is a fundamental result of mathematical logic obtained by Jacques Herbrand (1930).[1] It essentially allows a certain kind of reduction of first-order logic to propositional logic. Although Herbrand originally proved his theorem for arbitrary formulas of first-order logic,[2] the simpler version shown here, restricted to formulas in prenex form containing only existential quantifiers became more popular.

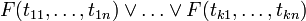

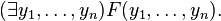

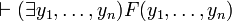

Let

be a formula of first-order logic with

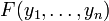

quantifier-free.

quantifier-free.

Then

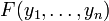

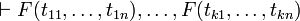

is valid if and only if there exists a finite sequence of terms:  , with

, with

and

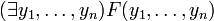

and  ,

,

such that

is valid. If it is valid,

is called a Herbrand disjunction for

Informally: a formula  in prenex form containing existential quantifiers only is provable (valid) in first-order logic if and only if a disjunction composed of substitution instances of the quantifier-free subformula of

in prenex form containing existential quantifiers only is provable (valid) in first-order logic if and only if a disjunction composed of substitution instances of the quantifier-free subformula of  is a tautology (propositionally derivable).

is a tautology (propositionally derivable).

The restriction to formulas in prenex form containing only existential quantifiers does not limit the generality of the theorem, because formulas can be converted to prenex form and their universal quantifiers can be removed by Herbrandization. Conversion to prenex form can be avoided, if structural Herbrandization is performed. Herbrandization can be avoided by imposing additional restrictions on the variable dependencies allowed in the Herbrand disjunction.

Proof Sketch

A proof of the non-trivial direction of the theorem can be constructed according to the following steps:

- If the formula

is valid, then by completeness of cut-free sequent calculus, which follows from Gentzen's cut-elimination theorem, there is a cut-free proof of

is valid, then by completeness of cut-free sequent calculus, which follows from Gentzen's cut-elimination theorem, there is a cut-free proof of  .

. - Starting from above downwards, remove the inferences that introduce existential quantifiers.

- Remove contraction-inferences on previously existentially quantified formulas, since the formulas (now with terms substituted for previously quantified variables) might not be identical anymore after the removal of the quantifier inferences.

- The removal of contractions accumulates all the relevant substitution instances of

in the right side of the sequent, thus resulting in a proof of

in the right side of the sequent, thus resulting in a proof of  , from which the Herbrand disjunction can be obtained.

, from which the Herbrand disjunction can be obtained.

However, sequent calculus and cut-elimination were not known at the time of Herbrand's theorem, and Herbrand had to prove his theorem in a more complicated way.

Generalizations of Herbrand's Theorem

- Herbrand's theorem has been extended to arbitrary higher-order logics by using expansion-tree proofs.[3] The deep representation of expansion-tree proofs correspond to Herbrand disjunctions, when restricted to first-order logic.

- Herbrand disjunctions and expansion-tree proofs have been extended with a notion of cut. Due to the complexity of cut-elimination, herbrand disjunctions with cuts can be non-elementarily smaller than a standard herbrand disjunction.

- Herbrand disjunctions have been generalized to Herbrand sequents, allowing Herbrand's theorem to be stated for sequents: "a skolemized sequent is derivable iff it has a Herbrand sequent".

See also

- Herbrand structure

- Herbrand interpretation

- Herbrand universe

- Compactness theorem

Notes

- ↑ J. Herbrand: Recherches sur la theorie de la demonstration. Travaux de la Societe des Sciences et des Lettres de Varsovie, Class III, Sciences Mathematiques et Physiques, 33, 1930.

- ↑ Samuel R. Buss: "Handbook of Proof Theory". Chapter 1, "An Introduction to Proof Theory". Elsevier, 1998.

- ↑ Dale Miller: A Compact Representation of Proofs. Studia Logica, 46(4), pp. 347--370, 1987.

References

- Buss, Samuel R. (1995), "On Herbrand's Theorem", in Maurice, Daniel; Leivant, Raphaël, Logic and Computational Complexity, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 195–209, ISBN 978-3-540-60178-4.