Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa 24 November 1864 Albi, Tarn, France |

| Died |

9 September 1901 (aged 36) Saint-André-du-Bois, France |

Resting place | Cimetière de Verdelais |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painter, printmaker, draughtsman, illustrator |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau |

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (24 November 1864 – 9 September 1901), also known as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French: [ɑ̃ʁi də tuluz lotʁɛk]) was a French painter, printmaker, draughtsman and illustrator whose immersion in the colourful and theatrical life of Paris in the late 19th century yielded a collection of exciting, elegant and provocative images of the modern and sometimes decadent life of those times. Toulouse-Lautrec is among the best-known painters of the Post-Impressionist period, a group which includes Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. In a 2005 auction at Christie's auction house, a new record was set when La blanchisseuse, an early painting of a young laundress, sold for US$22.4 million.[1]

Early life

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was born at the Hotel du Bosc in Albi, Tarn in the Midi-Pyrénées region of France, the firstborn child of Comte Alphonse Charles de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (1838–1913)[2] and wife Adèle Zoë Tapié de Celeyran (1841–1930).[3] He was therefore a member of an aristocratic family (descendants of the Counts of Toulouse and Lautrec and the Viscounts of Montfa, a village and commune of the Tarn department of southern France). A younger brother was born in 1867, but died the following year.

After the death of his brother his parents separated and a nanny took care of Henri.[4] At the age of eight, Henri went to live with his mother in Paris where he drew sketches and caricatures in his exercise workbooks. The family quickly realised that Henri's talent lay in drawing and painting. A friend of his father, René Princeteau, visited sometimes to give informal lessons. Some of Henri's early paintings are of horses, a speciality of Princeteau, and a subject Lautrec revisited in his 'Circus Paintings'.[4][5]

In 1875, Toulouse-Lautrec returned to Albi because his mother had recognised his health problems. He took thermal baths at Amélie-les-Bains and his mother consulted doctors in the hope of finding a way to improve her son's growth and development.[4]

Disability and health problems

Toulouse-Lautrec's parents, the Comte and Comtesse, were first cousins (his two grandmothers were sisters)[4] and he suffered from congenital health conditions sometimes attributed to a family history of inbreeding.[6]

At the age of 13, Toulouse-Lautrec fractured his right thigh bone and, at 14, the left.[7] The breaks did not heal properly. Modern physicians attribute this to an unknown genetic disorder, possibly pycnodysostosis (also sometimes known as Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome),[8] or a variant disorder along the lines of osteopetrosis, achondroplasia, or osteogenesis imperfecta.[9] Rickets aggravated with praecox virilism has also been suggested. His legs ceased to grow, so that as an adult he was extremely short (he stood at 4 ft 8 in (1.42 m)).[10] He had developed an adult-sized trunk, while retaining his child-sized legs.[11] He is reported to have had hypertrophied genitals.[12]

Physically unable to participate in many activities typically enjoyed by men of his age, Toulouse-Lautrec immersed himself in art. He became an important Post-Impressionist painter, art nouveau illustrator, and lithographer, and recorded in his works many details of the late-19th-century bohemian lifestyle in Paris. Toulouse-Lautrec contributed a number of illustrations to the magazine Le Rire during the mid-1890s.

After initially failing college entrance exams, he passed at his second attempt and completed his studies. During a stay in Nice his progress in painting and drawing impressed Princeteau, who persuaded his parents to let him return to Paris and study under the acclaimed portrait painter Léon Bonnat. Toulouse-Lautrec's mother had high ambitions and, with the aim of her son becoming a fashionable and respected painter, used the family influence to get him into Bonnat's studio.[4]

Paris

Toulouse-Lautrec was drawn to Montmartre, the area of Paris famous for its bohemian lifestyle and the haunt of artists, writers, and philosophers. Studying with Bonnat placed Henri in the heart of Montmartre, an area he rarely left over the next 20 years. After Bonnat took a new job, Henri moved to the studio of Fernand Cormon in 1882 and studied for a further five years and established the group of friends he kept for the rest of his life. At this time he met Émile Bernard and Vincent van Gogh. Cormon, whose instruction was more relaxed than Bonnat's, allowed his pupils to roam Paris, looking for subjects to paint. In this period Toulouse-Lautrec had his first encounter with a prostitute (reputedly sponsored by his friends), which led him to paint his first painting of prostitutes in Montmartre, a woman rumoured to be called Marie-Charlet.[4]

With his studies finished, in 1887 he participated in an exposition in Toulouse using the pseudonym "Tréclau", the verlan of the family name 'Lautrec'. He later exhibited in Paris with Van Gogh and Louis Anquetin.[4] The Belgian critic Octave Maus invited him to present eleven pieces at the Vingt (the Twenties) exhibition in Brussels in February. Van Gogh's brother, Theo bought 'Poudre de Riz' (Rice Powder) for 150 francs for the Goupil & Cie gallery.

From 1889 until 1894, Toulouse-Lautrec took part in the "Independent Artists' Salon" on a regular basis. He made several landscapes of Montmartre. At this time the 'Moulin Rouge' opened.[4] Tucked deep into Montmartre was the garden of Monsieur Pere Foret, where Toulouse-Lautrec executed a series of pleasant plein-air paintings of Carmen Gaudin, the same red-headed model who appears in The Laundress (1888). When the Moulin Rouge cabaret opened, Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to produce a series of posters. His mother had left Paris and, though he had a regular income from his family, making posters offered him a living of his own. Other artists looked down on the work, but Toulouse-Lautrec ignored them.[13] The cabaret reserved a seat for him and displayed his paintings.[14] Among the well-known works that he painted for the Moulin Rouge and other Parisian nightclubs are depictions of the singer Yvette Guilbert; the dancer Louise Weber, known as the outrageous La Goulue ("The Glutton"), who created the "French Can-Can"; and the much more subtle dancer Jane Avril.

London

_-_Henri_de_Toulouse-Lautrec.jpg)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's family were Anglophiles.[15] Though not as fluent as he pretended to be, he spoke English well enough to travel to London.[13] While there, he was commissioned by the J.& E. Bella company to make a poster advertising their confetti, (which was later banned after the 1892 Mardi Gras)[16] and the bicycle advert 'La Chaîne Simpson'.[17]

While in London he met and befriended Oscar Wilde.[13] When Wilde faced imprisonment in Britain, Toulouse-Lautrec became a very vocal supporter of his. Toulouse-Lautrec's portrait of Wilde was painted the same year as Wilde's trial.[13][18]

Alcoholism

Toulouse-Lautrec was mocked for his short stature and physical appearance, which led him to drown his sorrows in alcohol.[19]

He initially only drank beer and wine, but his tastes expanded into hard liquor namely absinthe.[20] The cocktail "Earthquake" or Tremblement de Terre is attributed to Toulouse-Lautrec: a potent mixture containing half absinthe and half cognac (in a wine goblet, three parts absinthe and three parts cognac, sometimes served with ice cubes or shaken in a cocktail shaker filled with ice).[21] To ensure he was never without alcohol, Toulouse-Lautrec hollowed out his cane (which he needed to walk due to his underdeveloped legs) which he filled with liquor.[13][22]

In addition to his growing alcoholism, Toulouse-Lautrec also had a fondness for frequenting prostitutes.[20] Toulouse-Lautrec was also fascinated by their lifestyle and the lifestyles of the "urban underclass" and later incorporated them into his paintings.[23] Fellow painter Édouard Vuillard later said that while Toulouse-Lautrec did engage in sex with prostitutes, "[...] the real reasons for his behavior were moral ones...Lautrec was too proud to submit to his lot, as a physical freak, an aristocrat cut off from his kind by his grotesque appearance. He found an affinity between his own condition and the moral penury of the prostitute."[24]

Death

By February 1899, Toulouse-Lautrec's alcoholism began to take its toll, and he collapsed due to exhaustion and the effects of alcoholism. His family had him committed to Folie Saint-James, a sanatorium in Neuilly for three months.[25] While he was committed, Toulouse-Lautrec drew 39 circus portraits. After his release, Toulouse-Lautrec returned to Paris studio for a time and then traveled throughout France.[26] His physical and mental health began to decline rapidly due to alcoholism and syphilis which he reportedly contracted from Rosa La Rouge, a prostitute that was the subject of several of his paintings.[27]

On 9 September 1901, he died from complications due to alcoholism and syphilis at the family estate, Château Malromé, in Saint-André-du-Bois at the age of 36. He is buried in Cimetière de Verdelais, Gironde, a few kilometres from his family's estate.[27][28] Toulouse-Lautrec's last words reportedly were: "Le vieux con!" ("The old fool!"). This was his goodbye to his father.[13] Although in another version he used the word "hallali", a term used by huntsmen for the moment the hounds kill their prey, "I knew, papa, that you wouldn't miss the death." ("Je savais, papa, que vous ne manqueriez pas l'hallali").[29]

After Toulouse-Lautrec's death, his mother, the Comtesse Adèle Toulouse-Lautrec, and Maurice Joyant, his art dealer, promoted his art. His mother contributed funds for a museum to be created in Albi, his birthplace, to house his works. The Toulouse-Lautrec Museum owns the world's largest collection of works by the painter.

Art

Throughout his career, which spanned less than 20 years, Toulouse-Lautrec created 737 canvases, 275 watercolours, 363 prints and posters, 5,084 drawings, some ceramic and stained glass work, and an unknown number of lost works.[8] His debt to the Impressionists, in particular the more figurative painters Manet and Degas, is apparent. His style was influenced by the classical Japanese woodprints which became popular in art circles in Paris. In his works can be seen parallels to Manet's detached barmaid at A Bar at the Folies-Bergère and the behind-the-scenes ballet dancers of Degas.

He excelled at depicting people in their working environments, with the colour and movement of the gaudy night-life present but the glamour stripped away, and was masterful when painting crowd scenes in which the figures are highly individualized. At the time that they were painted, the individual figures in his larger paintings could be identified by silhouette alone, and the names of many of these characters have been recorded. His treatment of his subject matter, whether as portraits, scenes of Parisian night-life, or intimate studies, has been described as both sympathetic and dispassionate.

Toulouse-Lautrec's skilled depiction of people relied on his painterly style which is highly linear and gives great emphasis to contour. He often applied the paint in long, thin brushstrokes which would often leave much of the board on which they are painted showing through. Many of his works may best be described as drawings in coloured paint.

Selected works

- See also Category:Paintings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Paintings

-

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh (1887), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

-

_1887-8.jpg)

Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) (1888)

-

The Laundress (1889)

-

At the Moulin Rouge (1890)

-

Portrait of Gabrielle (1891)

-

La Goulue arriving at the Moulin Rouge (1892)

-

At the Moulin Rouge: Two Women Waltzing (1892)

-

Quadrille at the Moulin Rouge (1892)

-

Jane Avril leaving the Moulin Rouge (c. 1892)

-

In Bed (1893)

-

Salon at the Rue des Moulins (1894)

-

The Medical Inspection at the Rue des Moulins Brothel (1894)

-

The clownesse Cha-U-Kao at the Moulin Rouge (1895)

-

Marcelle Lender doing the Bolero in 'Chilperic' (1895)

-

A box at the theater (1896)

-

_1899.jpg)

Le Coucher (1899)

Posters

-

_1891.jpg)

Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891)

-

Aristide Bruant in his cabaret (1892)

-

Ambassadeurs – Aristide Bruant (1892)

-

_1892.jpg)

Reine de Joie (1892)

-

Divan Japonais (1892-1893)

-

Avril (Jane Avril) (1893)

-

_1894.jpg)

The Photographer Sescau (1894)

-

_1894.jpg)

The German Babylon (1894)

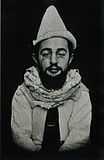

Photos

-

Mr. Toulouse paints Mr. Lautrec (ca. 1891)

-

Photo taken by Maurice Guibert (1892)

-

-

(ca. 1887)

In popular culture

Toulouse-Lautrec has been the subject of two biographical films and has been portrayed in others:

- In the John Huston film Moulin Rouge (1952), he is portrayed by José Ferrer.[10]

- Lautrec (1998) is a French biographical movie directed by Roger Planchon and starring Régis Royer as Toulouse-Lautrec.[30]

- In the 2001 film Moulin Rouge! Lautrec is portrayed by John Leguizamo.[28]

- In the Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris (2011), he is portrayed briefly by Vincent Menjou Cortes.

Stage productions:

- Lautrec (1999) is a musical written by Charles Aznavour that ran from 6 April to 17 June 2000 at the Shaftesbury Theatre in the West End of London.[31][32]

Books:

- Sacre Bleu (2012) written by Christopher Moore, is a work of fiction in which Lucien Lessard works with Toulouse-Lautrec to solve the mystery of Vincent van Gogh's death.[33]

- Moulin Rouge (1950), a biographical novel by Pierre La Mure, follows Lautrec through his whole life and contains vivid impressions of his family, his circumstances, and the milieu in which he lived and worked.

References

- ↑ Berwick, Carly (2 November 2005). "Toulouse-Lautrec Drives Big Night at Christie's". Nysun.com. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "count-alphonse-charles-de-toulouse-lautrec-monfa-1838-1913". gettyimages.co.uk.

- ↑ "HISTOIRE ET GÉNÉALOGIE DE LA FAMILLE de TOULOUSE-LAUTREC MONTFA et de ses alliances". genealogie87.fr. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Author Unknown, "Toulouse-Lautrec" – published Grange Books. ISBN 1-84013-658-8 Bookfinder – Toulouse Lautrec

- ↑ ArT Blog : Toulouse-Lautrec at the Circus: The "Horse and Performer" Drawings Blogs.princeton.edu

- ↑ Toulouse-Lautrec, H., Natanson, T., & Frankfurter, A. M. (1950). Toulouse-Lautrec: the man. N.p. p. 120. OCLC 38609256

- ↑ "Why Lautrec was a giant". The Times. UK. 10 December 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Angier, Natalie (6 June 1995). "What Ailed Toulouse-Lautrec? Scientists Zero In on a Key Gene". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ "Noble figure". The Guardian. UK. 20 November 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "The Shrinking of José Ferrer". Life (Time Inc) 33 (13): 51. September 29, 1952. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ↑ ""Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec". AMEA – World Museum of Erotic Art". Ameanet.org. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Ayto, John; Crofton, Ian (2006). Brewer's Dictionary of Modern Phrase & Fable. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 747. ISBN 0-304-36809-1.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 "Toulouse Lautrec: The Full Story". UK: Channel 4. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ↑ "Blake Linton Wilfong ''Hooker Heroes''". Wondersmith.com. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Joan (10 July 1994). "Book Review/ Short and not sweet: Toulouse-Lautrec: A Life - Julia Frey: Weidenfeld, pounds 25". independent.co.uk. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de; Donson, Theodore B. (1982). Great Lithographs by Toulouse-Lautrec. Griepp, Marvel M. Courier Corporation. p. XII. ISBN 0-486-24359-1.

- ↑ Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1896). "La Chaîne Simpson". San Diego Museum Of Art. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "'Oscar Wilde' 1895 by Toulouse-Lautrec". Mystudios.com. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Biography". lautrec.info.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Wittels, Betina; Hermesch, Robert (2008). Breaux, T. A., ed. Absinthe, Sip of Seduction: A Contemporary Guide. Fulcrum Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 1-933-10821-5.

- ↑ "Absinthe Service and Historic Cocktails". AbsintheOnline.com. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ Gately, Iain (2008). Drink, A Cultural History of Alcohol. Gotham books. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-592-40303-5.

- ↑ Powell, John; Blakeley, Derek W.; Powell, Tessa, ed. (2001). Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century, 1800-1914. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 417. ISBN 0-313-30422-X.

- ↑ (Toulouse-Lautrec, Donson 1982, p. XIV)

- ↑ Clair, Jean, ed. (2004). The Great Parade: Portrait of the Artist as Clown. Galeries nationales du Grand Palais (France), National Gallery of Canada. Yale University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-300-10375-1.

- ↑ (Toulouse-Lautrec, Donson 1982, p. V)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec Biography". toulouse-lautrec-foundation.org. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Bennett, Lennie (16 November 2003). "More than art's poster boy". St. Petersburg, Florida: sptimes.com. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "citations.com". citations.com. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ↑ Variety; Cowie, Peter (1999). Variety, ed. The Variety Insider. Penguin Group USA. p. 173. ISBN 0-399-52524-6.

- ↑ "History of the Shaftesbury Theatre".

- ↑ "Lautrec - Charles Aznavour - The Guide to Musical Theatre".

- ↑ "Christopher Moore". chrismoore.com.

Further reading

- Ives, Colta (1996). Toulouse-Lautrec in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870998041.

- Sawyer, Kenneth B. "Art Notes: Lautrec Works Shown at Gutman Memorial" 15 Apr. 1956 The Sun, 100.

- "Rites for Nelson Gutman to be at 11 A.M. Tomorrow" 17 Aug. 1955 The Sun,13.

- Henry, Helen. "Juanita Greif Gutman Art Treasures: Works form the Collection She Left the Baltimore Museum of Art Go on Exhibit Next Sunday" 16 Feb. 1964 The Sun, SM9.

- Gutman Show-Savor it Slow" 8 Mar. 1964 The Sun, D4.

- "Mrs. Gutman Funeral Set: Noted Collector of Art, Rare Books Traveled Widely" 7 Sept. 1963 The Sun, 1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec at the Museum of Modern Art

- Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre at the National Gallery of Art

- Factmonster page about Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de

- Toulouse-Lautrec and Paris exhibition at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Artcyclopedia

- Young woman at a table, 'Poudre de riz', 1887 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Collection Van Gogh Museum

- Toulouse Lautrec Museum

- (French) Bibliothèque numérique de l'INHA - Estampes de Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French National Institute of Art – Prints of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec)

- (French) The illness de Toulouse-Lautrec by N. Halkic, D. Gintzburger et E. Mouhsine

- Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril beyond the Moulin Rouge - Courtauld Gallery, London

- "Toulouse Lautrec Lecture" The Baltimore Museum of Art: Baltimore, Maryland, c. 1969-1970 Accessed June 26, 2012

- "Nelson and Juanita Grief Gutman Papers" The Baltimore Museum of Art: Baltimore Maryland

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Foundation.

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|