Hemiola

In music, hemiola (also hemiolia) is the ratio 3:2. The equivalent Latin term is sesquialtera.

Etymology

The word hemiola comes from the Greek adjective ἡμιόλιος, hemiolios, meaning "containing one and a half," "half as much again," "in the ratio of one and a half to one (3:2), as in musical sounds."[1] The early Pythagorians, such as Hippasus and Philolaus, used this term in a music-theoretic context to mean a perfect fifth.[2] Later authors such as Aristoxenus and Ptolemy use the word to describe smaller intervals as well, such as the hemiolic chromatic pyknon, which is one-and-a-half times the size of the semitone comprising the enharmonic pyknon.[3]

The words "hemiola" and "sesquialtera" both signify the ratio 3:2, and in music were first used to describe relations of pitch. Dividing the string of a monochord in this ratio produces the interval of a perfect fifth. Beginning in the 15th century, both words were also used to describe rhythmic relationships—specifically the substitution (usually through the use of coloration) of three imperfect notes for two perfect ones in tempus perfectum or in prolatio maior.[4]

Rhythm

In rhythm, hemiola refers to three beats of equal value in the time normally occupied by two beats.[5]

Vertical hemiola: sesquialtera

The Oxford Dictionary of Music shows hemiola as a vertical 3:2 (three beats simultaneous with two beats).[6]

One textbook states that, although the word "hemiola" is commonly used for both simultaneous and successive durational values, describing a simultaneous combination of three against two is less accurate than for successive values and the "preferred term for a vertical two against three … is sesquialtera."[7] The New Harvard Dictionary of Music states that in some contexts, a sesquialtera is equivalent to a hemiola.[8] Grove's Dictionary, on the other hand, has maintained from the first edition of 1880 down to the most recent edition of 2001 that the Greek and Latin terms are equivalent and interchangeable, both in the realms of pitch and rhythm,[9] although David Hiley holds that, though similar in effect, hemiola properly applies to a momentary occurrence of three duple values in place of two triple ones, whereas sesquialtera represents a proportional metric change between successive sections.[10]

Sub-Saharan African music

A repeating vertical hemiola is known as polyrhythm, or more specifically, cross-rhythm. The most basic rhythmic cell of sub-Saharan Africa is the 3:2 cross-rhythm. Novotney observes: "The 3:2 relationship (and [its] permutations) is the foundation of most typical polyrhythmic textures found in West African musics."[11] Agawu states: "[The] resultant [3:2] rhythm holds the key to understanding . . . there is no independence here, because 2 and 3 belong to a single Gestalt."[12]

In the following example, a Ghanaian gyil plays a hemiola as the basis of an ostinato melody. The left hand (lower notes) sounds the two main beats, while the right hand (upper notes) sounds the three cross-beats.[13]

European music

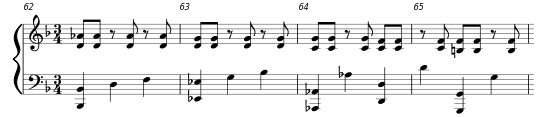

From around the 15th century, the term hemiola came to mean the use of three breves in a bar when the prevailing metrical scheme had two dotted breves in each bar.[14] This usage was later extended to its modern sense of two bars in simple triple time articulated or phrased as if they were three bars in simple duple time. An example can be found in measures 64 and 65 of this excerpt from the first movement of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Piano Sonata, K. 332:

The effect can clearly be seen in the bottom staff, played by the left hand: the accented beats are those with two notes; hearing this passage one senses that "1 2 3, 1 2 3, 1 2, 1 2, 1 2" is the musical pulse.

Hemiola is found in many Renaissance pieces in triple rhythm.

The hemiola was a common practice to end minuets in French baroque music. It is still the common practice when French baroque music is interpreted, either in historically correct fashion or otherwise. Often the term hemiolia is used in this case.

In modern musical parlance, a hemiola is a metrical pattern in which two bars in simple triple time (3/2 or 3/4 for example) are articulated as if they were three bars in simple duple time (2/2 or 2/4). In the example below, the third and fourth bars constitute the hemiola.

The interplay of two groups of three notes with three groups of two notes gives a distinctive pattern of 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2, 1-2.

In the modern sense, hemiolas often occur in certain dances, particularly the courante. Composers of classical music who have used the device particularly extensively include Arcangelo Corelli, George Frideric Handel, Carl Maria von Weber and most famously in the music of Johannes Brahms (e.g. the opening of Symphony no 3). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky frequently used hemiolas in his waltzes.

If the metrical impulse is not a three-beat pattern changing to a two beat one (as in the Mozart example above), but a two-beat impulse changing to a three-beat one, the pattern of 2:3 is called subsesquialtera.

Horizontal hemiola

Some musicians refer to the following figure as a horizontal hemiola.[15] The pattern consists of a triple beat scheme, followed by a duple beat scheme.

This figure is a common African bell pattern, used by the Hausa people of Nigeria, in Haitian Vodou drumming, Cuban palo, and many other drumming systems. The figure is also used in many sub-varieties of the Flamenco genre (Buleria,for example), and in various popular Latin American musics. The horizontal hemiola suggests metric modulation (3/4 changing to 6/8). This interpretational switch has been exploited, for example, by Leonard Bernstein, in the song "America" from West Side Story, as can be heard in the prominent motif (suggesting a duple beat scheme, followed by a triple beat scheme) ![]() Play :

Play :

Harmony

The perfect fifth

Hemiola is the ratio of the lengths of two strings, three-to-two (3:2), that together sound a perfect fifth.[16]

The justly tuned pitch ratio of a perfect fifth means that the upper note makes three vibrations in the same amount of time that the lower note makes two. In the cent system of pitch measurement, the 3:2 ratio corresponds to approximately 702 cents, or 2% of a semitone wider than seven semitones. The just perfect fifth can be heard when a violin is tuned: if adjacent strings are adjusted to the exact ratio of 3:2, the result is a smooth and consonant sound, and the violin sounds in tune. Just perfect fifths are the basis of Pythagorean tuning, and are employed together with other just intervals in just intonation. The 3:2 just perfect fifth arises in the justly tuned C major scale between C and G.[17] ![]() Play

Play

See also

References

- ↑ Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, 9th edition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940).

- ↑ Andrew Barker, Greek Musical Writings: [vol. 2] Harmonic and Acoustic Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989): 31, 37–38.

- ↑ Andrew Barker, Greek Musical Writings: [vol. 2] Harmonic and Acoustic Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989): 164–65, 303.

- ↑ Julian Rushton, "Hemiola [hemiolia]", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ↑ Don Michael Randel (ed.), New Harvard Dictionary of Music (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1986), p. 376.

- ↑ Michael Kennedy, The Oxford Dictionary of Music (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002): p. 398.

- ↑ Paul Cooper Perspectives in Music Theory; An Historical-Analytical Approach (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1973): p. 36.

- ↑ Don Randell, New Harvard Dictionary of Music (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986): p. 744.

- ↑ W[illiam] S[myth] Rockstro, "Hemiolia", A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1880), by Eminent Writers, English and Foreign, vol. 1, edited by George Grove, D. C. L., (London: Macmillan and Co., 1880): 727; Rockstro, W[illiam] S[myth], Sesqui, A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1883), by Eminent Writers, English and Foreign, vol. 3, edited by George Grove, D. C. L. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1883): 475; Julian Rushton, "Hemiola [hemiolia]", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001): 11:361

- ↑ David Hiley, E. Thomas Stanford/Paul R. Laird. "Sesquialtera", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001): 23:157–59.

- ↑ Eugene D. Novotney, "The Three Against Two Relationship as the Foundation of Timelines in West African Musics", thesis (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois. 1998), p. 201. Web: UnlockingClave.com.

- ↑ Kofi Agawu, Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (New York: Routledge, 2003) p. 92. ISBN 0-415-94390-6.

- ↑ Peñalosa, David (2009), The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins (Redway, CA: Bembe Inc.), p. 22. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ↑ Ruth I. DeFord, "Tempo Relationships between Duple and Triple Time in the Sixteenth Century", Early Music History 14 (1995): p. 1-51.

- ↑ Michael Tenzer (ed.), Analytical Studies in World Music (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006): p. 102.

- ↑ New Harvard Dictionary of Music (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986): p. 376.

- ↑ Oscar Paul, A Manual of Harmony for Use in Music-Schools and Seminaries and for Self-Instruction, trans. Theodore Baker (New York: G. Schirmer, 1885), p.165

Further reading

- Brandel, Rose (1959). The African Hemiola Style, Ethnomusicology, 3(3):106-17, correction, 4(1):iv.

- Karolyi, Otto (1998). Traditional African & Oriental Music, Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-023107-2.

| ||||||