Hemba people

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 90,000[1] |

| Languages | |

| Hemba language | |

The Hemba people (or Eastern Luba) are an ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

History

The Hemba language belongs to a group of related languages spoken by people in a belt that runs from southern Kasai to northeastern Zambia. Other peoples speaking related languages include the Luba of Kasai and Shaba, the Kanyok, Songye, Kaonde, Sanga, Bemba and the people of Kazembe.[2] Today the Hemba people live in the north of Zambia, and their language is understood throughout Zambia. Some also live in Tanzania. They live west of Lake Tanganyika and Lake Mweru in the DRC, and their villages are found several hundred miles up the Lualaba River.[3]

The Hemba people migrated eastward to the Lualaba valley from the Luba empire, probably some time after 1600.[4] They traded salt for iron hoes made in the Luba heartland, and wore raphia cloth that came by way of the Luba from the Songye people further to the west.[5] At the time of the eastward expansion of the Luba Kingdom under King Ilunga Sungu around 1800, Hemba people were living in a territory bounded by the Lukuga River in the north, the Luvua River in the south and the Lualaba River to the west.[6] The lower Lukuga and the Lualaba provided natural lines of communication, and the river valleys were densely populated.[7]

During Ilunga Sungu's rule the southern Hemba became tributaries to the Luba. They were headed by a "fire king", who symbolically represented the Luba king.[8] The Hemba fire kingdom cut its links to the Luba empire after Ilunga Sungu died. His successor, Kumwimbe Ngombe, had to fight several campaigns to recover the eastern territories.[9] Kumwimbe created a client state that united the Hemba villages of the Lukushi River valley, and that played an important role in preserving Luba dominance over other small states in the region.[10] Later the Hemba regained their independence, but were subject to attacks by Arab slave traders in the later part of the nineteenth century, and then to colonization by the Belgians.[1]

Culture

The Hemba people live in villages, recognizing chiefs as their political leaders. A chief will be the head of an extended family of landowners, inheriting his title through the maternal line.[1] Hemba people may also belong to secret societies such as the Bukazanzi for men and Bukibilo for women.[11] The So'o secret society is guarded by the beautifully carved mask of a chimpanzee, which is used in rituals that relate to the ancestral spirits.[12] These societies serve to offset the power of the chief.[11]

Although the Luba people failed to keep the southern Hemba in their kingdom they did have considerable cultural influence. Art forms, including wooden sculptures representing ancestors, are similar in style to Luba sculptures. The Hemba religion recognizes a creator god and a separate supreme being. The Hemba make sacrifices and present offerings at the shrines of ancestors. When social harmony has been upset, religious leaders may demand offerings to the specific ancestors that have become displeased and are causing the trouble.[1] Each clan owns a kabeja, a statuette with one body and two faces, male and female, on one neck. Sacrifices are made to the kabeja, which will convey them to the spirits. A receptacle on the top of the kabeja is used to receive magic incredients. A kabeja is dangerous to handle.[11]

Economy

The villagers live by subsistence agriculture, growing manioc, maize, peanuts, and yams. They also hunt and fish to a small extent to supplement their diet. Cash is obtained through panning alluvial copper from the streams.[1] Many Hemba men are also employed as miners in the copperbelt.[13]

Gallery of Hemba artwork

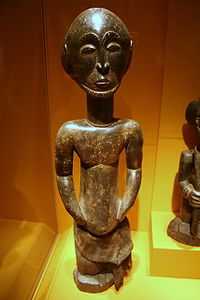

The Hemba artistic tradition is well-known. Subjects include ancestral figures, spirits, human faces and ceremonial masks.[14]

-

Mask from the Bakali-Kwenge region

-

Warrior Ancestor Figure; 19th century

-

Male figure, Niembo chiefdom, late 19th to early 20th century

-

Male figure, Niembo chiefdom, late 19th to early 20th century

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Hemba Information.

- ↑ Reefe 1981, p. 74.

- ↑ Olson 1996, pp. 223-224.

- ↑ Mukenge 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ Reefe 1981, p. 98.

- ↑ Reefe 1981, p. 124.

- ↑ Reefe 1981, p. 131.

- ↑ Reefe 1981, p. 127.

- ↑ Macola 2002, p. 108.

- ↑ Reefe 1981, p. 137.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Tribal African Art.

- ↑ Alesha 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ Olson 1996, p. 224.

- ↑ Mukenge 2002, p. 76.

Sources

- Alesha, Matomah (2004). Sako ma: a look at the sacred monkey totem. Matam Press. ISBN 1-4116-0643-4.

- "Hemba Information". University of Iowa. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- Macola, Giacomo (2002). The kingdom of Kazembe: history and politics in North-Eastern Zambia and Katanga to 1950. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 3-8258-5997-5.

- Mukenge, Tshilemalema (2002). Culture and customs of the Congo. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31485-3.

- Olson, James Stuart (1996). The peoples of Africa: an ethnohistorical dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-27918-7.

- Reefe, Thomas Q. (1981). The rainbow and the kings: a history of the Luba Empire to 1891. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04140-2.

- "Tribal African Art - Hembe (Bahembe)". Zyama. Retrieved 2011-12-12.