Hellas Planitia

|

Viking orbiter image mosaic of Hellas Planitia | |

| Planet | Mars |

|---|---|

| Region | Hellas quadrangle, south of Iapygia |

| Coordinates | 42°24′S 70°30′E / 42.4°S 70.5°ECoordinates: 42°24′S 70°30′E / 42.4°S 70.5°E |

| Diameter | 2,300 km (1,400 mi) |

| Depth | 7,152 m (23,465 ft) |

Hellas Planitia is a plain located within the huge, roughly circular impact basin Hellas[lower-alpha 1] located in the southern hemisphere of the planet Mars.[3] Hellas is the second or third largest impact crater and the largest visible impact crater known in the Solar System. The basin floor is about 7,152 m (23,465 ft) deep, 3,000 m (9,800 ft) deeper than the Moon's South Pole-Aitken basin, and extends about 2,300 km (1,400 mi) east to west.[4][5] It is centered at 42°24′S 70°30′E / 42.4°S 70.5°E.[3] Hellas Planitia is in the Hellas quadrangle and the Noachis quadrangle.

Description

With a diameter of about 2,300 km (1,400 mi),[6] it is the largest unambiguous impact structure on the planet, though a distant second if the Borealis Basin proves to be an impact crater. Hellas Planitia is thought to have been formed during the Late Heavy Bombardment period of the Solar System, approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago, when a large asteroid hit the surface.[7]

The altitude difference between the rim and the bottom is 9,000 m (30,000 ft). The depth of the crater (7,152 m (23,465 ft)[1] ( 7,000 m (23,000 ft)) below the standard topographic datum of Mars) explains the atmospheric pressure at the bottom: 12.4 mbar (0.012 bar) during the northern summer .[8] This is 103% higher than the pressure at the topographical datum (610 Pa, or 6.1 mbar or 0.09 psi) and above the triple point of water, suggesting that the liquid phase could be present under certain conditions of temperature, pressure, and dissolved salt content.[9] It has been theorized that a combination of glacial action and explosive boiling may be responsible for gully features in the crater.

Some of the low elevation outflow channels extend into Hellas from the volcanic Hadriacus Mons complex to the northeast, two of which Mars Orbiter Camera images show contain gullies: Dao Vallis and Reull Vallis. These gullies are also low enough for liquid water to be transient around Martian noon, if the temperature would rise above 0 Celsius.[10]

Hellas Planitia is antipodal to Alba Patera.[11][12][13] It and the somewhat smaller Isidis Planitia together are roughly antipodal to the Tharsis Bulge, with its enormous shield volcanoes, while Argyre Planitia is roughly antipodal to Elysium, the other major uplifted region of shield volcanoes on Mars. Whether the shield volcanoes were caused by antipodal impacts like that which produced Hellas, or if it is mere coincidence, is unknown.

-

MOLA map showing boundaries of Hellas Planitia and other regions

-

Geographic context of Hellas

-

Apparent viscous flow features on the floor of Hellas, as seen by HiRISE.

-

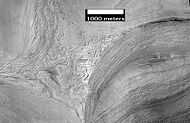

Twisted terrain in Hellas Planitia (actually located in Noachis quadrangle).

Discovery and naming

Due to its size and its light coloring, which contrasts with the rest of the planet, Hellas Planitia was one of the first Martian features discovered from Earth by telescope. Before Giovanni Schiaparelli gave it the name Hellas (which in Greek means 'Greece'), it was known as 'Lockyer Land', having been named by Richard Anthony Proctor in 1867 in honor of Sir Joseph Norman Lockyer, an English astronomer who, using a 16 cm (6.3 in) refractor, produced "the first really truthful representation of the planet" (in the estimation of E. M. Antoniadi).[14]

Possible glaciers

Radar images by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft's SHARAD radar sounder suggest that features called lobate debris aprons in three craters in the eastern region of Hellas Planitia are actually glaciers of water ice lying buried beneath layers of dirt and rock.[15] The buried ice in these craters as measured by SHARAD is about 250 m (820 ft) thick on the upper crater and about 300 m (980 ft) and 450 m (1,480 ft) on the middle and lower levels respectively. Scientists believe that snow and ice accumulated on higher topography, flowed downhill, and is now protected from sublimation by a layer of rock debris and dust. Furrows and ridges on the surface were caused by deforming ice.

Also, the shapes of many features in Hellas Planitia and other parts of Mars are strongly suggestive of glaciers, as the surface looks as if movement has taken place.

Layers

-

Layers in depression in crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program A special type of sand ripple called Transverse aeolian ridges, TAR's are visible and labeled.

See also

- Argyre Planitia

- Gale crater

- Geography of Mars

- Glaciers

- List of plains on Mars

- Water on Mars

- Glaciers on Mars

- Groundwater on Mars

- Dune

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Martian Weather Observation MGS radio science measured 11.50 mbar at 34.4° S 59.6° E -7152 meters

- ↑ "Hellas". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Science Center. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Hellas Planitia". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Science Center. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ The part below zero datum, see Geography of Mars#Zero elevation

- ↑ Remote Sensing Tutorial Page 19-12, NASA

- ↑ Schultz, Richard A.; Frey, Herbert V. (1990). "A new survey of multi-ring impact basins on Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research 95: 14175–14189. Bibcode:1990JGR....9514175S. doi:10.1029/JB095iB09p14175.

- ↑ Acuña, M. H. et al. (1999). "Global Distribution of Crustal Magnetization Discovered by the Mars Global Surveyor MAG/ER Experiment". Science 284 (5415): 790–793. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..790A. doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.790. PMID 10221908.

- ↑ "...the maximum surface pressure in the baseline simulation is only 12.4 mbar. This occurs in the bottom of the Hellas basin during northern summer", JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 106, NO. El0, PAGES 23,317-23,326, OCTOBER 25, 2001, On the possibility of liquid water on present-day Mars, Robert M. Haberle, Christopher P. McKay, James Schaeffer, Nathalie A. Cabrol, Edmon A. Grin, Aaron P. Zent, and Richard Quinn.

- ↑ Making a Splash on Mars, NASA, 29 June 2000

- ↑ Heldmann, Jennifer L. et al. (2005). "Formation of Martian gullies by the action of liquid water flowing under current Martian environmental conditions". Journal of Geophysical Research 110: E05004. Bibcode:2005JGRE..11005004H. doi:10.1029/2004JE002261. para 3 page 2 Martian Gullies Mars#References

- ↑ Peterson, J. E. (March 1978). "Antipodal Effects of Major Basin-Forming Impacts on Mars". Lunar and Planetary Science IX: 885–886. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ↑ Williams, D. A.; Greeley, R. (1991). "The Formation of Antipodal-Impact Terrains on Mars". Lunar and Planetary Science XXII: 1505–1506. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ↑ Williams, D. A.; Greeley, R. (August 1994). "Assessment of Antipodal-Impact Terrains on Mars". Icarus 110 (2): 196–202. Bibcode:1994Icar..110..196W. doi:10.1006/icar.1994.1116. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ↑ William Sheehan. "The Planet Mars: A History of Observation and Discovery". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ↑ NASA. "PIA11433: Three Craters". Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- J. N. Lockyer, Observations on the Planet Mars (Abstract), Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 23, p. 246

- E. M. Antoniadi, The Hourglass Sea on Mars, Knowledge, July 1, 1897, pp. 169–172.

Recommended reading

- Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hellas Planitia. |

- The Hellas Of Catastroph, Peter Ravenscroft, 2000-08-16, Space Daily

- Google Mars scrollable map - centered on Hellas

- Martian Ice - Jim Secosky - 16th Annual International Mars Society Convention