Heart transplantation

| Heart transplantation | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

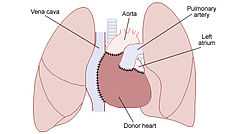

Diagram illustrating the placement of a donor heart in an orthotopic procedure. Notice how the back of the patient's left atrium and great vessels are left in place. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 37.51 |

| MeSH | D016027 |

| MedlinePlus | 003003 |

A heart transplant, or a cardiac transplant, is a surgical transplant procedure performed on patients with end-stage heart failure or severe coronary artery disease. As of 2008 the most common procedure is to take a working heart from a recently deceased organ donor (cadaveric allograft) and implant it into the patient. The patient's own heart is either removed (orthotopic procedure) or, less commonly, left in place to support the donor heart (heterotopic procedure). Post-operation survival periods average 15 years.[1] Heart transplantation is not considered to be a cure for heart disease, but a life-saving treatment intended to improve the quality of life for recipients.[2]

History

Norman Shumway is widely regarded as the father of heart transplantation although the world's first adult human heart transplant was performed by a South African cardiac surgeon, Christiaan Barnard, utilizing the techniques developed and perfected by Shumway and Richard Lower.[3] Barnard performed the first transplant on Louis Washkansky on December 3, 1967 at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa.[3][4] Adrian Kantrowitz performed the world's first pediatric heart transplant on December 6, 1967, at Maimonides Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, barely three days after Christiaan Barnard's pioneering procedure.[3] Norman Shumway performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States on January 6, 1968, at the Stanford University Hospital.[3]

Worldwide, about 3,500 heart transplants are performed annually. The vast majority of these are performed in the United States (2,000-2,300 annually). Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, currently is the largest heart transplant center in the world, having performed 119 adult transplants in 2013 alone. About 800,000 people have NYHA Class IV heart failure symptoms indicating advanced heart failure.[5] The great disparity between the number of patients needing transplants and the number of procedures being performed spurred research into the transplantation of non-human hearts into humans after 1993. Xenografts from other species and man-made artificial hearts are two less successful alternatives to allografts.[1]

Contraindications

Some patients are less suitable for a heart transplant, especially if they suffer from other circulatory conditions related to the heart. The following conditions in a patient increase the chances of complications:

- Kidney, lung, or liver disease

- Insulin-dependent diabetes with other organ dysfunction

- Life-threatening diseases unrelated to heart failure

- Vascular disease of the neck and leg arteries.

- High pulmonary vascular resistance

- Recent thromboembolism

- Age over 60 years (some variation between centers)

- Substance abuse, notably tobacco smoking (which increases the chance of lung disease)

Procedures

Pre-operative

A typical heart transplantation begins when a suitable donor heart is identified. The heart comes from a recently deceased or brain dead donor, also called a beating heart cadaver. The patient is contacted by a nurse coordinator and instructed to come to the hospital for evaluation and pre-surgical medication. At the same time, the heart is removed from the donor and inspected by a team of surgeons to see if it is in suitable condition. Learning that a potential organ is unsuitable can induce distress in an already fragile patient, who usually requires emotional support before returning home.

The patient must also undergo emotional, psychological, and physical tests to verify mental health and ability to make good use of a new heart. The patient is also given immunosuppressant medication so that the patient's immune system does not reject the new heart.

Operative

Once the donor heart passes inspection, the patient is taken into the operating room and given a general anaesthetic. Either an orthotopic or a heterotopic procedure follows, depending on the conditions of the patient and the donor heart.

Orthotopic procedure

The orthotopic procedure begins with a median sternotomy, opening the chest and exposing the mediastinum. The pericardium is opened, the great vessels are dissected and the patient is attached to cardiopulmonary bypass. The donor's heart is injected with potassium chloride (KCl). Potassium chloride stops the heart beating before the heart is removed from the donor's body and packed in ice. Ice can usually keep the heart usable for four[6] to six hours depending on preservation and starting condition. The failing heart is removed by transecting the great vessels and a portion of the left atrium. The patient's pulmonary veins are not transected; rather a circular portion of the left atrium containing the pulmonary veins is left in place. The donor heart is trimmed to fit onto the patient's remaining left atrium and the great vessels are sutured in place. The new heart is restarted, the patient is weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass and the chest cavity is closed.

The orthotopic procedure was developed by Shumway and Lower at Stanford-Lane Hospital in San Francisco in 1958.[3]

Heterotopic procedure

In the heterotopic procedure, the patient's own heart is not removed. The new heart is positioned so that the chambers and blood vessels of both hearts can be connected to form what is effectively a 'double heart'. The procedure can give the patient's original heart a chance to recover, and if the donor's heart fails (e.g., through rejection), it can later be removed, leaving the patient's original heart. Heterotopic procedures are used only in cases where the donor heart is not strong enough to function by itself (because either the patient's body is considerably larger than the donor's, the donor's heart is itself weak, or the patient suffers from pulmonary hypertension).

'Living organ' transplant

In February 2006, at the Bad Oeynhausen Clinic for Thorax and Cardiovascular Surgery, Germany, surgeons successfully transplanted a 'beating heart' into a patient.[7] Rather than cooling the heart, the living organ procedure keeps it at body temperature and connects it to a special machine called an Organ Care System that allows it to continue pumping warm, oxygenated blood. This technique can maintain the heart in a suitable condition for much longer than the traditional method.

Non-beating heart transplant

The first successful non-beating heart transplant was achieved in Australia in 2014, performed by cardiothoracic surgeon Kumud Dhital. The transplant was made possible by the development of preservation technology able to preserve a heart, resuscitate it and to assess the function of the heart. The first patient to have this surgery was 57-year-old Michelle Gribilas.[8] Papworth Hospital in England (where the first non-beating heart transplant in Europe was carried out) stated that the technique could increase the number of hearts available for transplant by at least 25%. [9]

Post-operative

The patient is taken to the ICU to recover. When they wake up, they move to a special recovery unit for rehabilitation. The duration of in-hospital, post-transplant care depends on the patient's general health, how well the heart is working, and the patient's ability to look after the new heart. Doctors typically prefer that patients leave the hospital 1–2 weeks after surgery, because of the risk of infection and presuming no complications. After release, the patient returns for regular check-ups and rehabilitation. They may also require emotional support. The frequency of hospital visits decreases as the patient adjusts to the transplant. The patient remains on immunosuppressant medication to avoid the possibility of rejection. Since the vagus nerve is severed during the operation, the new heart beats at around 100 beats per minute unless nerve regrowth occurs.

Immunosuppressive agents are continued in the intensive care unit.

The patient is regularly monitored to detect rejection. This surveillance can be performed via frequent biopsy or a gene expression blood test known as AlloMap Molecular Expression Testing. Typically, biopsy is performed immediately post-transplant and then AlloMap replaces it once the patient is stable. The transition from biopsy to AlloMap can occur as soon as 55 days after the transplant.

Complications

Post-operative complications include infection, sepsis, organ rejection, as well as the side-effects of the immunosuppressive medication. Since the transplanted heart originates from another organism, the recipient's immune system typically attempts to reject it. The risk of rejection never fully goes away, and the patient will be on immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of his or her life, but these may cause unwanted side effects, such as increased likelihood of infections, like fevers, unusual pains, or any new feelings. Recipients can get kidney disease from a heart transplant. Many recent advances in reducing complications due to tissue rejection stem from mouse heart transplant procedures.[10] Surgery death rate is 5-10% in 2011.[11] Hong Kong death rate is 5% for 16 patients from beginning to 2014.[12]

Prognosis

The prognosis for heart transplant patients following the orthotopic procedure has increased over the past 20 years, and as of June 5, 2009, the survival rates were:[13]

- 1 year: 88.0% (males), 86.2% (females)

- 3 years: 79.3% (males), 77.2% (females)

- 5 years: 73.2% (males), 69.0% (females)

In a study spanning 1999 to 2007, conducted on behalf of the U.S. federal government by Dr. Eric Weiss of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, it was discovered that, compared to men receiving male hearts, "men receiving female hearts had a 15% increase in the risk of adjusted cumulative mortality" over five years. No significant differences were noted with females receiving hearts from male or female donors.[14]

Notable recipients

At the time of his death on August 10, 2009, Tony Huesman was the world's longest living heart transplant recipient, having survived for 30 years, 11 months and 10 days, before dying of cancer.[15] Huesman received a heart in 1978 at the age of 20 after viral pneumonia severely weakened his heart.[16] The operation was performed at Stanford University under heart transplant pioneer Dr. Norman Shumway.[17]

As of December 2013, the record holder for longest living heart recipient is Englishman John McCafferty, 71. He received his heart on 20 October 1982.[15]

Kelly Perkins climbs mountains around the world to promote positive awareness of organ donation. Perkins was the first recipient to climb the peaks of Mt. Fuji, Mt. Kilimanjaro, the Matterhorn, Mt. Whitney, and Cajon de Arenales in Argentina in 2007, 12 years after her surgery.

Twenty-two years after Dwight Kroening's heart transplant, he was the first recipient to finish an Ironman competition.[18]

Fiona Coote was the fourth Australian to receive a heart transplant in 1984 (at age 14) and the youngest Australian. In the 24 years after her transplant she became involved in publicity and charity work for the Red Cross, and promoted organ donation in Australia.

Race car driver and manufacturer Carroll Shelby received a heart transplant in 1990.[19]

Golfer Erik Compton qualified for the PGA Tour at age 32, after his second heart transplant.[20]

Former Vice President of the United States Dick Cheney received a heart transplant on March 24, 2012.[21]

Former chairman and founder of MCI Communications William G. McGowan received a heart transplant on April 25, 1987.[22] After a six-month recovery, McGowan returned to his duties as MCI chairman where he remained until his death on June 8, 1992 from another heart attack.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Till Lehmann (director) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ↑ Burch, M., & Aurora, P. (2004). Current status of paediatric heart, lung, and heart-lung transplantation. Archives of disease in childhood, 89(4), 386–389.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 McRae, D. (2007). Every Second Counts. Berkley.

- ↑ "Memories of the Heart". Doylestown, Pennsylvania: Daily Intelligencer. November 29, 1987. p. A–18.

- ↑ Reiner Körfer (interviewee) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ↑ Custodiol Htk Solution patient advice including side effects

- ↑ "Bad Oeynhausen Clinic for Thorax- and Cardiovascular Surgery Announces First Successful Beating Human Heart Transplant". TransMedics. 23 February 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ↑ "‘Dead’ hearts transplanted into living patients in world first".

- ↑ BBC News http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-32056350. Retrieved 16 April 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Bishay, R. The ‘ Mighty Mouse’ Model in Experimental Cardiac Transplantation. Hypothesis 2011, 9(1): e5.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3082109/

- ↑ tvb

- ↑ Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2012 Update The American Heart Association. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ Weiss, E. S.; Allen, J. G.; Patel, N. D.; Russell, S. D.; Baumgartner, W. A.; Shah, A. S.; Conte, J. V. (2009). "The Impact of Donor-Recipient Sex Matching on Survival After Orthotopic Heart Transplantation: Analysis of 18 000 Transplants in the Modern Era". Circulation: Heart Failure 2 (5): 401. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.844183.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Prynne, Miranda (24 December 2013). "Brit sets new record for longest surviving heart transplant patient". The Daily Telegraph (United Kingdom). Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ http://www.columbusdispatch.com/live/content/local_news/stories/2009/08/10/aheart.html?sid=101

- ↑ Heart Transplant Patient OK After 28 Yrs (14 September 2006) CBS News. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- ↑ Dwight Kroening first heart transplant to do ironman Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ↑ Glick, Shav (31 January 1996). "Kidney Transplant a Success for Shelby". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "New heart, new hope: Golfer Compton achieves PGA Tour dream". CNN. 24 January 2012.

- ↑ "Cheney undergoes heart transplant surgery". Fox News. 24 March 2012.

- ↑ LESLIE WAYNE (March 27, 1988). "TOGETHER APART". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ↑ "William G. McGowan: Monopoly Buster". Entrepreneur. October 10, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

External links

- - The real first heart transplant.

- Official Heart Transplant Museum - Heart Of Cape Town

- Photograph of first U.S. heart transplant

- Western Cape government, South Africa (21 February 2005). "Chris Barnard Performs World's First Heart Transplant". Cape Gateway. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery. "Patient's Guide to Heart Transplant Surgery". University of Southern California. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Nancy Reid (22 September 2005). "Heart transplant: How is it performed?". Healthwise. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Jeffrey Everett (2003-10-29). "Heart Transplant: Indications". AllRefer.com. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- The Adrian Kantrowitz Papers Profiles in Science from the National Library of Medicine for Adrian Kantrowitz, the first to perform a pediatric heart transplant

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||