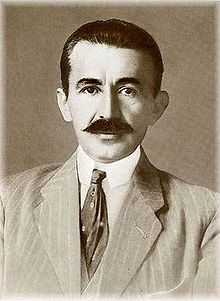

Hasan Prishtina

| Hasan Prishtina | |

|---|---|

| |

| 8th Prime Minister of Albania | |

| In office 7 December 1921 – 12 December 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Qazim Koculi |

| Succeeded by | Idhomene Kosturi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1873 Glogovac, Ottoman Empire (today Kosovo) |

| Died | August 1933 (aged 60) Thessaloniki, Greece |

| Resting place | Kukës, Albanian Kingdom |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Religion | Islam |

Hasan Prishtina originally known as Hasan Berisha[1][2][3] (born 1873 in Drenas[4] Kosovo Vilayet, Ottoman Empire – died 1933 in Thessaloniki, Greece) was an Albanian politician, who served as Prime Minister of Albania in December 1921.[5]

Biography

Family and early life

According to Ivo Banac and Miranda Vickers, Hasan was a member of the Šiškovic clan of Vučitrn.[6][7] His father Ahmed Berisha moved from the Vučitrn kaza to Poljance in 1871, where Hasan was born in 1873.[8] After finishing the French gymnasium in Thessaloniki, he studied politics and law in Istanbul.

He initially supported the Young Turks and was elected to the Ottoman parliament in 1908. He changed his last name into Prishtina in 1908, when he was elected as a Prishtina delegate[2][3] in the Ottoman National Parliament in Istanbul during the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire.[5] However, Prishtina lost his position in 1912 as did all the Albanian deputies.

Albanian National Movement

After the Ottoman Government did not keep their promises for more rights and independence to the Albania nation, Hasan Prishtina and several other prominent Albanian intellectuals started organizing the Albanian National Movement. He together with Isa Boletini and Bajram Curri took the responsibility to start the Albanian National Movement in Kosovo.

Prishtina took an active part in the 1912 uprising in Kosovo and formulated the autonomy demands that were submitted to the Turkish government in August 1912, the so-called fourteen points of Hasan Prishtina.

| “ | The fourteen points of Hasan Prishtina state:

|

” |

Until August 1912, Prishtina led the Albanian rebels to gain control over the whole Kosovo vilayet (including Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Priština and even Skopje), part of Scutari Vilayet (including Elbasan, Përmet, Leskovik and Konitsa in Janina Vilayet and Debar in Monastir Vilayet.[9]

Albanian Independence and World War I

In December 1913, after Albanian independence, he served as minister of agriculture, and in March 1914 was made minister of postal services in the government of Independent Albania led by Ismail Qemali.

During the First World War he organized divisions of volunteers to fight for Austria-Hungary.[10] In 1918, after the Serb occupation of his native Kosovo from Austria-Hungary, Prishtina, together with Bajram Curri, fled to Vienna and later to Rome, where he was in contact with Croatian, Macedonian and Montenegrin opponents of the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[11] Hasan Prishtina became a head of the Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo in Rome in 1918.[12]

Political career

Hasan Prishtina was in charge of the delegation of the Committee in December 1919 which represented Albanians for the protection of their rights in the Paris Peace Conference, where he requested the unification of Kosovo and Albania. The Kosovar delegation was, however, not given leave to participate in the debates.

Prishtina then returned to Albania where in January 1920 he helped organise the Congress of Lushnjë and in April 1921 became a member of parliament for Dibra.[11] He took part in a coup d'état that year and served as Primer minister for a brief five days from 7 to 12 December, but was forced out of office by Ahmet Zogu, who was a Minister of Interior at that time and regarded it as imperative to avoid conflict with Belgrade.[11]

Thereafter, Hasan helped organise uprisings in Kosovo and led several antigovernment insurrections in Albania, the latter being easily suppressed by the administrations of Xhafer Bej Ypi and Ahmet Zogu.[11]

He returned to Tirana during the Democratic Revolution of 1924 under Fan Noli, whom he accompanied to the League of Nations in Geneva.

Exile and death

When Zogu took power in December 1924, Hasan bey Prishtina was forced to leave Albania. As he could not return to Kosovo, he settled in Thessalonika where he purchased a large estate.[11] Hasan Prishtina is known to have been very rich, and sold almost all his property to finance the education of Albanians from Kosovo in universities around Europe, and for the armed resistance, during all his life.

Like most Kosovo politicians, Hasan bey Prishtina was a sworn enemy of Ahmet Zogu, the two having attempted to assassinate one another.[11] He was imprisoned by Yugoslav police for a period, was released in 1931. In 1933, he was killed by Ibrahim Celo[11] in a cafe in Thessalonika on the orders of King Zog and the Serbian government.[13] His mansion in the city is currently used as Thessaloniki's school for children with visual impairment.

Legacy

Hasan Prishtina is commemorated in Kosovo and Albania. In 1993, when a meeting commemorating the 60th anniversary of his death was convened in Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbian police raided the place and showed machine guns to the participants. Out of 80 participants, 37 were arrested and the rest were beaten for 5 to 15 minutes by police.[14] In 2012 a statue of Prishtina was elevated in Skopje in Skanderbeg Square .

See also

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Unknown |

Member of the Ottoman Parliament as representative of Pristina 1908–1912 |

Succeeded by Post abolished |

| Preceded by Qazim Koculi |

Prime Minister of Albania 7 December 1921 – 12 December 1921 |

Succeeded by Idhomene Kosturi |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ "Hasan bey Prishtina, originally known as Hasan Berisha..."Historical Dictionary of Kosovo Volume 79 of Historical Dictionaries of Europe G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series Volume 79 of European historical dictionaries Author Robert Elsie Edition 2, illustrated Publisher Scarecrow Press, 2010 ISBN 0-8108-7231-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-7231-8 page 223-224

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Hasan Bey Prishtina (ursprünglich Hasan Berisha) (Geboren 1873 in Drenas/Kosovo – 1933 in Thessaloniki) Aus einer Großgrundbesitzerfamilie stammend, studierte Hasan Berisha in Istanbul Jura... im ersten Parlament des Osmanischen Reiches und namh den namen "Prishtina" .. und fuhrte den titel bey...(Hasan Bey Prishtina (originally Hasan Berisha) (Born in 1873 in Drenas / Kosovo - 1933 in Thessaloniki) Born into a landowning family, studied law in Istanbul as Hasan Berisha. In 1908 he was a deputy in the first parliament of the Ottoman Empire and took the name "Prishtina" ..and the title bey)" KOSOVO Informieren-Reisen-Erinnern Author Susanne Dell Editor Susanne Dell Publisher BoD – Books on Demand, 2010 ISBN 3-8391-9179-3, ISBN 978-3-8391-9179-8 page 113-114

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Prishtina, Hasan Bey, albanischer Politiker, * Drenas (Kosovo) 1873, f (ermordet) Saloniki 14. VIII. 1933, Sohn des Ahmed Berisha, der um 1871 aus dem Dorf Poljance in Drenica nach Vucitrn übersiedelte, ..Im Dezember 1908 wurde P. als Abgeordneter Pristinas ins turkischeParlament gewahlt; das war auch der zeitpunkt, wo er seinen Familiennamen in Prishtina.... (Prishtina, Hasan Bey, the Albanian politicians, * Drenas (Kosovo) 1873, f (assassinated) Salonika 14th VIII, 1933, son of Ahmed Berisha, who around 1871 moved from the village poljance in Drenica to Vucitrn ... In December 1908, p chosen as a Pristina delegate to the turkish Parlament, which was also the time when he changed his family name in Prishtina ....)" Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas, Volume 3 Volume 75 of Südosteuropäische Arbeiten Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas, Felix von Schroeder Editors Mathias Bernath, Felix von Schroeder Publisher Oldenbourg Verlag, 1979 ISBN 3-486-48991-7, ISBN 978-3-486-48991-0 page 485-468

- ↑ Dérens, Jean-Arnault (2006). Kosovo, année zéro. Harvard College Library: Paris Paris-Méditerranée 2006. p. 365. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: a short history. Macmillan. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-333-66612-8. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ Vickers, Miranda (1998). Between Serb and Albanian : a history of Kosovo. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-231-11383-0. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

Hasan Pristina (1873-1933), 23 who came from the powerful Siskovic clan in Vucitrn,

- ↑ Banac, Ivo (1988). Nacionalno pitanje u Jugoslaviji : porijeklo, povijest, politika (in Croatian). Zagreb: Globus. p. 283. ISBN 978-86-343-0237-0. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

Hasan-beg Prish- tina (ili Šišković, iz Vučitrna, kojega su Srbi držali srpskim narodnim izdajni- "

- ↑ "Prishtina was born in 1873 in the village of Polac in the District of Drenica." Studia Albanica, Volume 27, Issue 2

- ↑ Bogdanović, Dimitrije (November 2000) [1984]. "Albanski pokreti 1908-1912.". In Antonije Isaković. Knjiga o Kosovu (in Serbian) 2. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

... ustanici su uspeli da ... ovladaju celim kosovskim vilajetom do polovine avgusta 1912, što znači da su tada imali u svojim rukama Prištinu, Novi Pazar, Sjenicu pa čak i Skoplje... U srednjoj i južnoj Albaniji ustanici su držali Permet, Leskoviku, Konicu, Elbasan, a u Makedoniji Debar...

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2011). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo (2 ed.). London: Scarecrow Press. p. 224. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

He spent World War I organizing divisions of volunteers to fight for Austria-Hungary

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Elsie, Robert (2011). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo (2 ed.). London: Scarecrow Press. p. 224. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

In 1918, after the Serb occupation of his native Kosovo he fled abroad with Bajram Curri to Vienna and then to Rome

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2011). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo (2 ed.). London: Scarecrow Press. p. 224. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

and became a head of the Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo

- ↑ Gail Warrander, Verena Knaus (2010). Kosovo, 2nd: The Bradt Travel Guide (2 ed.). Connecticut: the globe pequot press. p. 87. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (Organization : U.S.) (1993). Open wounds: human rights abuses in Kosovo. Human Rights Watch. pp. 57–60. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

Further reading

- O.S. Pearson, Albania and King Zog, I.B. Tauris. 2005 (ISBN 1-84511-013-7).

|