Harvard Musical Association

The Harvard Musical Association is a private charitable organization founded by Harvard University graduates in 1837 for the purposes of advancing musical culture and literacy, both at the University and in the city of Boston. Though initially a spin-off of the Pierian Sodality, the Association broke its ties with Harvard soon after its founding.[1] The Association's most important notable accomplishments include the creation of the country's finest music library of the time,[2] the sponsorship of the first professional and public chamber music series in the United States,[3] the erection of the Boston Music Hall, and the formation of the orchestra which ultimately gave rise to the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The Association's library catalog may be searched on OCLC with the initials HVDMA.

History

Founding

In July 1837, the Pierian Sodality, a society of musically inclined Harvard undergraduates, held its annual meeting. They proposed the organization of a new society, the chief object of which would be "...the promotion of musical taste and science in the University...to enrich the walls of Harvard with a complete musical library...and to prepare the way for regular musical instruction in the College." By general agreement, and with the help of various past members, the organization now known as The Harvard Musical Association was created at a subsequent meeting on August 30, 1837 under the name "The General Association of Past and Present Members of the Pierian Sodality". The name was shortened in 1840.

The new Association, advocating the teaching of music at Harvard, sent the following series of resolutions to Josiah Quincy, Harvard's president at that time.[3]

| “ |

|

” |

Proposals from outsiders for the improvement of the University were considered presumptuous and Quincy never acknowledged that he had received the document.[4] It was not until 1862, when John Knowles Paine was appointed Harvard's first professor of music, that music became an established part of the curriculum.[5] In light of the College's attitude and decreasing undergraduate participation,[3] the membership agreed not to mention Harvard at its meetings (a ban that remained in effect for twenty-four years) and turned its capacities toward the advancement of music in Boston.

Music in Boston

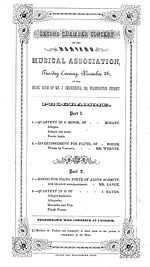

The Association's first undertaking was the establishment of an annual lecture series, delivered on erudite musical topics by qualified individuals. The lecture series in itself lasted five years, with speakers Henry R. Cleveland (1840), John Sullivan Dwight (1841), William Whetmore Story (1842), Ezra Weston (1843), and Christopher P. Cranch (1845). Starting in 1842, chamber concerts accompanied the annual lectures.[6]

From 1844 to 1849, the Association sponsored a series of chamber music concerts open to the public. Though this concert series lasted only five years, it had a profound impact on music in the United States, both by increasing public knowledge of chamber music, and by helping music in general gain legitimacy as an art form.[7]

| “ | By 1850, the Harvard Musical Association had, in three relatively successful seasons, not only established the string quartet as a viable public medium but also in approximately five years drastically altered the musical landscape of America. By 1850 the idea that instrumental music could stand as art with the best of literature and the visual arts was firmly in place. | ” |

— Michael Broyles, Music Historian[7] |

In 1850, under the leadership of member Dr. Jabez Upham, the Association raised in sixty days the sum of US$100,000 to build a new Music Hall between Tremont and Washington Streets. This hall, seating over two thousand, was dedicated by Jenny Lind in 1852. Ten years later the members of the Association raised an additional $60,000 to install in the hall an organ built in Germany by Walcker. Regarded as the largest organ in the United States, this instrument contained 5,474 pipes and 84 registers and may now be heard (altered by Æolian–Skinner) in its own hall in Methuen.[8]

On December 28, 1865, the Association began its sponsorship of public concerts by the Harvard Orchestra, conducted by Carl Zerrahn. Of these concerts, which took place in the Music Hall, King's Dictionary of Boston reported in 1883: "The greatest works of the greatest masters have been given at these concerts, the standard of whose programmes has been kept at the highest, with the view, in part, of educating the taste of the musical public in what is greatest and best without regard to fashion or popular demand." The orchestra, however, had humble beginnings. Though composed of sixty-two players, the orchestra often lacked necessary instruments. As Arthur Foote said: "When a harp was needed in the orchestra..., one of us would do the best we could to replace it by playing its part on an upright piano." In 1882, after having suffered monetary losses for eight years, the Harvard Orchestra was dissolved and turned over the last of its funds, $1,000 to the Association.[2]

Association member Henry Lee Higginson, however, sought to revivify orchestra music in Boston, and in 1881 placed an ad in the Boston newspapers, which would lead to the creation of the first professional symphony orchestra in Boston:[1]

| “ | [...] The orchestra is to number sixty selected musicians; their time, so far as required for careful training and for a given number of concerts, to be engaged in advance.

Mr. George Henschel will be the conductor for the coming season. The concerts will be twenty in number, given in the Music Hall on Saturday evenings, from the middle of October,m to the middle of March. The intention is that this orchestra shall be made permanent here, and shall be called "The Boston Symphony Orchestra."[2] |

” |

Although Higginson had intended for members of Harvard Orchestra to play in the new one, most were not good enough musicians to reach the level of perfection required to fulfill Higginson's hopes for the professional orchestra. After the disbanding of the Harvard Orchestra in 1882, the Association stopped all direct participation in the Boston music scene, and continued to host concerts for the pleasure of members only.[9]

Library

The Association's library, however, remained open to the public, and is still an integral part of the Association's daily operations. With bequeaths from various members, it soon assembled many books and scores which were assessed by the Salem Register in 1843 as constituting the "largest and best musical library in the country." Today, the library has over 11,000 volumes, including many rare and notable works.[2] A few examples:[10]

- A collection of sheet music published by the Van Hagens, the first sheet music publishers in Boston

- An archive of the complete running of Dwight's Musical Journal

- Malcolm Alexander's A Treatise of Musick, Speculative, Practical, and Historical, the first history of music in the English language.

- A signed first edition of César Franck's Pièces [cinq] pour harmonium

- A first edition of Mozart's Sei quartetti per due violin, viola, e violoncello

Premiere of Parsifal

In 1880, German composer Richard Wagner encountered difficulty in getting Parsifal performed in Bayreuth. Annoyed because of his large expenditures on the Festival Theater, the venue at which he had intended to hold the performance, and bureaucratic opposition, he said in a letter to American dentist Newell S. Jenkins: "It seems to me as if, in my hopes of regarding Germany and her future, my patience would very soon be exhausted."[11] In a display of his notorious ego,[12] Wagner proposed that if an American organization would give him $1,000,000, he would agree to come to the United States, to live there permanently, and to put on the first performance of Parsifal. Jenkins forwarded the letter to Andrew D. White—then the American ambassador to the German Empire—who in turn sent it to John Sullivan Dwight. Although the Association briefly considered the proposal, Wagner's difficulties in Bayreuth were resolved before any plans were finalized.[11] Parsifal was produced in 1882, and Wagner died the following year.

Locations

"Social evenings" for members and guests were held first in Cambridge and then in such renowned Boston locations as the Revere House, the Tremont House, and the original Parker House. Then, the Association would gather ten to twelve times a year to hear some of the leading chamber musicians of the day and to share a post-concert supper. Whether the white-tie-and-oyster affair of the 19th century or the baked bean, Welsh rarebit, and ale collation of the present, the social evening remains the heart of the organization.

From its beginning and through the 1880s, the Association's rooms were moved from time to time. From 1858 to 1869, its Library was placed in the Athenæum. In 1892, the Association acquired the Malcolm Greenough (brother of Horatio Greenough) house at 1 West Cedar Street. Opened with a reception for Antonín Dvořák, this has remained the Association's residence for over 100 years. The main floor was dropped four feet in 1907, which required relocating the main entrance to Chestnut Street and taking a new number, 57A.[4] With a bequest from Julia Marsh, widow of Charles Marsh (member Eben Jordan's partner), the Association renovated the upper floors in 1913. The third floor, with its warren of leased rooms, was gutted and the resulting space joined to the second floor to create space for a highly ornamented, double-height hall (designed by member architect Joseph Everett Chandler, a Colonial Revival specialist) thereafter known as the Marsh Room. The condition of Marsh's bequest was that the room in her honor be open during weekdays (provided there's no Association gathering) to local musicians for practice.

Famous members

Of the builders of the Association, particular mention should be made of John Sullivan Dwight, a noted transcendentalist and member of the Brook Farm movement, who for many years published a recondite Journal of Music and was widely known as one of the nation's outstanding musicologists. It was largely through his efforts that the Library was established, the Music Hall was built, and the Harvard Orchestra was organized. He served as President of the Association from 1873 until his death in 1893, at which time he was a resident in the new house of the Association.[13]

Other significant figures in the Association's affairs include Henry Ware, Jr., first President; Henry White Pickering, President from 1852 to 1873; Arthur Foote, the celebrated composer, who importantly reorganized the Library during his membership from 1875 to 1937; and Charles R. Nutter, historian of the Association and an active member from 1893 to 1965.[14]

Courtenay Guild, an important figure during the first half of the 20th century, served as President of the Association for twenty-five of the sixty years he was a member. At his death in 1946, a substantial portion of his estate was bequeathed to the Association and added to its capital funds.

Following the retirement of Richard Wait, a Boston lawyer, as President of the Association in 1979, and in light of his unprecedented thirty-one years in office, the concert hall on the first floor was named in his honor as the Richard Wait Room.

Recent years

HMA Orchestra

Drawing its initial members from former players of instruments in the Pierian Sodality (now the Harvard–Radcliffe Orchestra) and later from others who in adult life continued to practice their instruments, it is not surprising that members of the Association should have participated in numerous orchestras and ensembles. Notable among these was the Harvard Alumni Orchestra which met under the direction of Jacques Hoffman in the 1920s, giving several public concerts. The current orchestra for members grew out of the efforts of John Codman in 1947. It was first directed by Malcolm Holmes, then also Director of the Pierian Sodality. Following his death in 1953, it has continued under the leadership of Chester Williams, a member of the Association and former Dean of the New England Conservatory of Music. The current orchestra is substantially less active than some predecessors: its most recent public concert was in 1948.

Philanthropy and awards

Support of music by the Association in recent years has taken different forms. In the late 1950s, it offered awards for the best original compositions of chamber music, for which over eighty compositions were submitted. The Association has given scholarship aid to various schools of music and small grants to symphony, opera, chamber music, and ballet organizations.

In 1985, the Association initiated the annual High School Achievement Awards program to reward promising classical musicians in the greater Boston area of secondary school age. Terence Hsu, New England Preparatory School pianist, won the 2007-2008 Awards and performed a recital on March 28, 2008 at the Association. The recital was attended by over 100 invited guests, and included the "Waldstein" Sonata by Ludwig van Beethoven as well as notable etudes by Alexander Scriabin, Moritz Moszkowski, and Sergei Rachmaninoff. Awarded a $2,000 cash prize, Terence Hsu, 16, in addition to being a prolific pianist, is also a violinist and composer.[15] In 1990, it established the Arthur W. Foote Prize in honor of teacher, composer, and performer member Arthur W. Foote. The Foote Prize is given annually to a performer or group who is attending an East Coast university and who is on the way to a successful career. Entrants are considered by the Foote Prize Committee and the winner is awarded $5,000 and gives a concert at the Association.[16]

Events and performances

In 1987, the Association celebrated its sesquicentennial. The Association's most valued achievement that year was its commissioning of John Harbison's Second String Quartet. The Association also co-sponsored the work's premiere performance by the Emerson String Quartet. A Sesquicentennial Dinner was held at the St. Botolph Club. New works continue to be commissioned from time to time, including in the last several years compositions by John Bavicchi, Arthur Berger, John Huggler, Thomas Oboe Lee, and Thomas McGah.

In October 1992, the Association marked the centennial of its arrival at 57A Chestnut Street by reproducing the opening of one hundred years earlier. The Wait Room was decorated with flowers, lobster shells, stuffed quail, and pomegranates. Champagne and Cotuit oysters were followed by the congregational singing of a Latin anthem written for the Association. The house's inaugural concert was performed, consisting of Beethoven's Archduke Trio, Handel's "O, Ruddier than the Cherry", two songs by Bach, and Beethoven's "Adelaide". After these performances and hors d'œuvres, ninety members of the Association ascended to the Marsh Room where, over the next three hours, a seven-course candlelight feast was consumed. The seven accompanying wines came from the same regions, and in three instances the same vineyards, as those served in 1892. Dr. Richard W. Dwight (a member of the Association since 1933) and Mrs. Helen Roelker Kessler (grand-niece of an early member of the Association, Bernard Roelker, whose Fund of Convivial Impulses subsidized the Centennial gala), delivered speeches.

Renovations

Improvements to the Association's rooms both for the comfort of members and guests as well as for the safety of the building and collections have been the major undertakings during the past nine years. Kilmer McCully, president from 1994 to 1997 began the program of improvements with the design and construction of new men's and ladies' rooms and a new commercial kitchen. During the presidency of Rina Spence (1997–2000) an elevator was installed to permit handicapped access to three out of five floors at 57A. Under Presidents Dr. John B. Little (2000–2003) and J. Stephen Friedlaender (2003–2006), the Association provided its building with an automatic fire suppression system as well as an archival storage area. Through a member-led effort, the recording archive of the 300 concerts from 1951 to 1971 were transcoded from magnetic tape to CDs and the catalogue of recordings placed online. Current projects include making the HMA catalogue accessible online and evaluating the preservation needs of the collections.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 H. C. Colles (1935). "The Harvard Musical Association". The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Boston: Macmillan.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hepner, Arthur W. (1987). Pro Bono Artium Musicarum: The Harvard Musical Association, 1837-1987. Boston: The Harvard Musical Association.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Paige, Paul E. (Summer 1970). "Chamber Music in Boston: The Harvard Musical Association". Journal of Research in Music Education (The National Association for Music Education) 18 (2): 134–142. doi:10.2307/3344266. JSTOR 3344266.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nutter, Charles R. (1937). The Harvard Musical Association, 1837-1937. Boston: Anchor Printing Company. p. 26.

- ↑ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.>. "John Knowles Paine". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. ISSN 0031-8299.

- ↑ Elson, Louis C. (1899). The National Music of America and Its Sources. Boston: L. C. Page and Company. pp. 290–1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Broyles, Michael. "An Address on the Occasion of a Sesquicentennial Re-Enactment of the First Professional Chamber Music Concert in Boston" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ Sampson Jr., Edward J. "Methuen Memorial Music Hall History". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ Dwight, John Sullivan (1888). Address by the President of the Association at the Dinner Celebrating the 50th Anniversary. Boston: The Harvard Musical Association. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Smith, Carlton Sprague. "Notable Items in the Collection of Harvard Musical Association" (DOC). Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Nutter, Charles R. (1954). Bulletins Nos. 15-22, 1947-1954. Boston: The Harvard Musical Association. Bulletin No. 21.

- ↑ Gutman, Robert W. (1990). Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind, and His Music. Orlando, Florida: Harvest Books [Harcourt].

- ↑ Robinson, David. "John Sullivan Dwight". Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ Metcalf, Nelson H. (November 30, 1910). "The Harvard Musical Association". Harvard Alumni Bulletin. pp. 1–3.

- ↑ The High School Achievement Awards Committee. "High School Achievement Awards Notice" (DOC). The Harvard Musical Association. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ The Foote Prize Committee. "The Arthur W. Foote Prize" (RTF). The Harvard Musical Association. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- Broyles, Michael. Music of the Highest Class: Elitism and Populism in Antebellum Boston New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press 0300054955