Hartebeest

- "Kongoni" redirects here. For the GNU/Linux distribution, see Kongoni (operating system).

| Hartebeest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coke's hartebeest, Ngorongoro, Tanzania | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Alcelaphus |

| Species: | A. buselaphus |

| Binomial name | |

| Alcelaphus buselaphus Pallas, 1766 | |

| Subspecies | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus) is an African species of grassland antelope, first described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Adults stand just over 1 m (3.3 ft) at the shoulder. Males weigh 125 to 218 kg (276 to 481 lb), and females are slightly lighter. The coat colour varies between subspecies, from the sandy coat of the western hartebeest to the almost black coat of the Swayne's hartebeest. Both sexes have horns; these grow 45–70 cm (18–28 in) long, with the shape varying greatly between subspecies. Hartebeest live between 11 and 20 years in the wild, and up to 19 in captivity.

Hartebeest are social animals that form herds of 20 to 300 individuals. Generally calm in nature, hartebeest can be ferocious when provoked. Their diets consist mainly of grasses, with small amounts of Hyparrhenia grasses and legumes throughout the year. The time of mating varies seasonally, and depends on both the subspecies and the population. Hartebeest are sexually mature at one to two years of age. After a gestation period of eight months, one offspring is born. The hartebeest inhabits savannas, woodlands, and open plains.

Each of the eight subspecies of the hartebeest has a different conservation status. The Bubal hartebeest was declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 1994. The hartebeest was formerly widespread in Africa, but populations have undergone drastic decline due to habitat destruction, hunting, human settlement, and competition with domestic cattle for food. The hartebeest is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Lesotho, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Tunisia. It has been introduced into Swaziland and Zimbabwe. It is a popular game animal due to its highly regarded meat.

Etymology

The common name "hartebeest" is derived from the Afrikaans hertebeest.[3] The name was given by the Boers, who thought it resembled deer.[4] In Dutch, the word hert means "deer", and beest means "beast".[4] The name was first used in South African literature in Dutch colonial administrator Jan van Riebeeck's journal Daghregister during 1660. He wrote: "Meester Pieter ein hart-beest geschooten hadde (Master Pieter [van Meerhoff] had shot one hartebeest)".[5]

Evolution

The genus Alcelaphus emerged about 4.4 million years ago in a clade, with Damalops, Numidocapra, Rabaticeras, Megalotragus, Oreonagor, and Connochaetes as the other members.[6] An analysis using phylogeographic patterns within the hartebeest suggested a possible origin of the antelope in eastern Africa. The species is believed to have later spread into the rest of the continent. Phylogenetic analyses showed an early genetic diversification to have occurred in the southern and northern hartebeest lineages. The northern lineage has further diverged into eastern and western lineages, most probably as a result of the expanding central African rainforest belt and subsequent contraction of savannah habitats during a period of global warming. These major events throughout the hartebeest's evolution are strongly related to climatic factors, which could play a vital role in learning more of the species' evolutionary history.[7] Fossils of the red hartebeest have been found in Elandsfontein, Cornelia and Florisbad in South Africa, as well as in Kabwe in Zambia.[8]

Hartebeest are known since the Natufian and Neolithic times well into the Bronze and Iron Ages. In Israel, hartebeest remains were found in open landscape, northern Negev, Shephelah, and Sharon Plain. Latest fossils have been traced in Tel Lachish. It was originally limited to the open country of the southernmost regions of southern Levant. The hartebeest was probably hunted in Egypt, which affected the numbers in Levant, and disconnected it from its main population in Africa.[9]

Taxonomy

First described by German zoologist and botanist Peter Simon Pallas in 1766, the hartebeest still bears its original scientific name Alcelaphus buselaphus. It is classified in the genus Alcelaphus.[2] The species can be assigned to three major divisions on the basis of skull structure: A. buselaphus division (also including 'major' division); A. tora division (also including A. cokii and A. swaynei); and A. lelwel division. More genetic details show similarities between the A.lelwel and A.tora divisions.[2]

The taxonomic ranking of the Lichtenstein's hartebeest has been disputed. Zoologists Jonathan Kingdon and Theodor Haltenorth supported it as a subspecies of A. buselaphus.[10] In 1979, palaeontologist Elisabeth Vrba supported Sigmoceros as a separate genus for this hartebeest,[11] based on the species' closer affinity to Connochaetes; she dissolved the new genus later in 1997 after reconsideration.[12] An MtDNA analysis could find no evidence to support a separate genus. It also showed the tribe Alcelaphini to be monophyletic, and discovered close affinity between the Alcelaphus and Damaliscus taxa - both genetically and morphologically.[13]

Subspecies

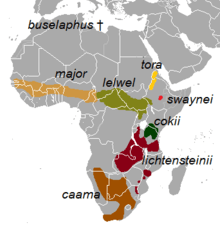

Many taxa were introduced as syntypes for this species, due to which fixing a lectotype was required. Six species recognised by former authors were later assigned as subspecies for the hartebeest, when hybridization between some of the subspecies was shown to be possible.[2] These subspecies have been recognised:[1][2]

- † A. b. buselaphus (Pallas, 1766), the Bubal hartebeest or northern hartebeest,[14] was formerly distributed in northern Africa. The last individual was shot in Algeria, and it was declared extinct in 1996 by the IUCN.[15][16]

- A. b. caama (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803), the red hartebeest or Cape hartebeest, is popular as a game animal.[17] The subspecies is widespread and common in Africa, and its population is increasing.[18] It is sometimes considered its own species, Alcelaphus caama.[2]

- A. b. cokii (Gunther, 1884), the Coke's hartebeest or kongoni, is native to Kenya and Tanzania.[19]

- A. b. lelwel (Heuglin, 1877), the Lelwel hartebeest, is found in the Central African Republic, southern Chad, north-east Democratic Republic of the Congo, south-west Ethiopia, Kenya, southern Sudan, extreme north-western Tanzania, and northern and western Uganda.[20] Drastic population decrease has confined most individuals to protected areas.[21]

- A. b. lichtensteinii (Peters, 1849), Lichtenstein's hartebeest, inhabits the miombo woodlands of eastern and southern Africa. It has also been treated as a separate species.[22] It is native to Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[23]

- A. b. major (Blyth, 1869), the western hartebeest, is distributed eastward from Senegal to northern Cameroon.[24]

- A. b. swaynei (P. L. Sclater, 1892), Swayne's hartebeest, is often confused with the Tora hartebeest due to physical similarities.[25] It is found only in Ethiopia and its population is decreasing.[26]

- A. b. tora (Gray, 1873), the Tora hartebeest, is distributed in north-west Ethiopia and Eritrea.[27]

-

_Bubalis_busephalus.png)

A. b. buselaphus

-

_Bubalis_caama.png)

A. b. caama

-

_Bubalis_cokei.png)

A. b. cokii

-

_Bubalis_lichtensteini.png)

A. b. lichtensteinii

-

_Bubalis_swaynei.png)

A. b. swaynei

The Jackson's hartebeest, another type of hartebeest, does not have a clear taxonomic status. The first record of this hartebeest was at the Bronx Zoo (USA) in 1913.[28] It is regarded as a hybrid between the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest. The IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (ASG) refers to the cross as the Kenyan hartebeest and the Ugandan Lelwel hartebeest as identical to the Jackson's hartebeest.[28] The African Antelope Database (1998) refers to it as synonymous to the Lelwel hartebeest.[29] This hartebeest occurs where the ranges of the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest overlap - from western Kenya through Karamoja district (north-western Uganda).[28] It is replaced by the Lelwel hartebeest towards the west of the Nile.[30]

Genetics and hybrids

Both the red hartebeest and Swayne's hartebeest populations in Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary and Nechisar National Park have been found to have a high degree of genetic variation. Even among the Swayne's hartebeest populations, those from the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary showed more genetic diversity than the ones from the Nechisar National Park. Many mitochondrial haplotypes and microsatellite alleles present at high frequencies among the Senkele individuals were missing in Nechisar. As a result, conservation and breeding programmes have been suggested to maintain the genetic diversity of these populations.[31]

The diploid number of chromosomes in the hartebeest is 40. A male sterile hybrid has been proved possible between the red hartebeest and the blesbok (Damaliscus dorcas), whose diploid number of chromosomes is 38. Difficulties in segregation during meiosis of the hybrid were thought to be a cause of the offspring's sterility. Azoospermia and fewer germ cells in the cross-section of the seminiferous tubules were also reasons cited for this defect.[32]

Two subspecies cross-breeds are recognised by some sectors of the commercial hunting fraternity.

- Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel x cokii: The Kenya Highland hartebeest is a cross between the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest. This hybrid is lighter in colour and larger than the Coke's hartebeest. Its coat is a light buff, and the head is longer than the Coke's hartebeest. Both sexes have horns, which are heavier, as well as longer, than the parents. It was formerly distributed throughout western Kenyan highlands, between Lake Victoria and Mount Kenya, but is now believed to be restricted to the Lambwe Valley (south-west Kenya) and Laikipia and nearby regions of west-central Kenya.[33]

- Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel x swaynei : The Neumann hartebeest is named after traveller and sportsman A. H. Neumann. This is a cross between the Lelwel hartebeest and Swayne's hartebeest. American zoologist Edmund Heller had asserted it to be a cross between A. b. nakura, a subspecies he described, and A. b. lelwel.[34] The face is longer than that of the Swayne's hartebeest. The colour of the coat is a golden brown, paler towards the underparts. The chin is blackish and the tail tuft black. Both sexes have longer horns than the Swayne's hartebeest. The horns grow in a wide "V" shape, unlike the wide bracket shape of Swayne's hartebeest and the narrow "V" of Lelwel hartebeest. Found in Ethiopia, it has spread in a small area to the east of Omo River and north of Lake Turkana, stretching north-east of Lake Chew Bahir to near Lake Chamo.[35]

Description

The hartebeest stands just over 1 m (3.3 ft) at the shoulder, and has a head-and-body length of 150 to 245 cm (59 to 96 in).[36] Females weigh from 116 to 185 kg (256 to 408 lb); males weigh from 125 to 218 kg (276 to 481 lb).[37] The tail is 30 to 70 cm (12 to 28 in) long, ending with a black tinge.[36] The other distinctive features of the hartebeest are its long legs (often with black markings),[14] short neck, and pointed ears.[37] Apart from its long face, the large chest and sharply sloping back of the hartebeest can be used to distinguish it from other antelopes.[3] Lifespan is 11 to 20 years in the wild and up to 19 in captivity.[36] The hartebeest shares physical traits with the sassabies (genus Damaliscus), such as an elongated and narrow face, horn shapes, pelage texture and colour, and the terminal tuft of the tail. The wildebeest has more specialised skull and horn features than the hartebeest.[38]

The coat is generally short and shiny.[38] Coat colour varies by subspecies; the large western hartebeest has a light and dull, sandy-brown pelage,[24] and the Tora hartebeest's is dark.[27] The red hartebeest, as its name implies, has a fully red pelage.[39] The Coke's hartebeest is reddish tawny on the upper side and a lighter colour on the dorsal part.[40] Lelwel hartebeest are a reddish-tan.[20] While the upper parts are reddish tan, the lateral part is a light tan and the rump whitish in the Lichtenstein's hartebeest.[41] Lichtenstein's hartebeest also possesses dark stripes on its front legs.[14][41] Swayne's and Tora hartebeest are very similar in appearance, as both have small heads, dark coats, and similar horns. The Swayne's hartebeest is the smaller of the two and has slightly shorter and heavier horns.[25][38] Fine textured, the body hair of the hartebeest is about 25 mm (0.98 in) long.[11] The hartebeest has preorbital glands with a central duct. They secrete a dark sticky fluid in Coke's and Lichtenstein's hartebeest, while in the Lelwel hartebeest it is a colourless secretion.[38]

Both sexes of all subspecies have horns, with the females' being more slender.[37] Horns can reach lengths of 45–70 cm (18–28 in).[36] The horns of the hartebeest curve slightly outwards, and then point back inwards. Most of the bottom parts of the horns have distinctive rings.[37] The diversity among the subspecies is in the shape of the horns and by their coloration. The red hartebeest has "Z"-shaped horns,[39] while the Lichtenstein's has horns form a crumpled "S" shape.[41] Both Swayne's and Tora hartebeest have lyre-shaped horns.[27] Lelwel hartebeest have thick, "V"-shaped horns,[20] and the Coke's has short, thick, bracket-shaped horns.[40] Western hartebeest have massive, "U"-shaped horns.[24] Horns are used for defence from predators, and during fights among males for dominance in the breeding season.[42]

The hartebeest exhibits slight sexual dimorphism, as both sexes bear horns and have similar body masses. The degree of sexual dimorphism varies by subspecies. Males are 8% heavier than females in Swayne's and Lichtenstein's hartebeest, and 23% heavier in the red hartebeest. In one study, the highest dimorphism was found in skull weight.[43] In another study, the length of the breeding season was a good predictor of dimorphism in pedicle (bony structures from which horns grow) height and skull weight, and the best predictor of the horn circumference.[42]

Ecology and behaviour

Like most antelopes, the hartebeest is diurnal. It grazes in the early morning and the late afternoon, and rests in shade during the hottest part of the day. They are social animals, and form herds of up to 300. Larger numbers gather in places with plenty of grass.[37] The largest herd recorded was of 10,000 animals. The members of a herd can be divided into four groups: territorial adult males, nonterritorial adult males, young males, and the females with their young. The females form groups of five to 12 animals, with four generations of young in the group. Females fight for dominance over the herd.[44] Sparring between males and females is common.[28] At three or four years of age, the males can attempt to take over a territory and the female members. A resident male defends its territory and will fight if provoked.[43] The male marks the border of its territory through defecation.[28] The beginning of a fight is marked with a series of head movements and stances, as well as depositing droppings on dung piles. The opponents drop on their knees and, after giving a hammer-like blow, begin wrestling, their horns interlocking. One attempts to fling the other's head to one side to stab the neck and shoulders with its horns.[43] Males generally lose their territory after seven or eight years.[36] A video of a hartebeest head-butting a bicyclist has been interpreted as territorial behavior.[45]

During feeding, one individual stays on the lookout for danger, often standing on a termite mound to see farther. At times of danger, the whole herd flees in single file after one suddenly starts off.[44] The hartebeest is more alert and cautious than other ungulates.[46] Adult hartebeest are preyed upon by lions, leopards, hyenas and wild dogs; cheetahs and jackals hunt juveniles.[44] Both hartebeest and sassabies produce quiet quacking and grunting sounds. The hartebeest uses defecation as an olfactory and a visual display.[38] Herds migrate only during times of extreme need, such as during natural calamities and droughts.[47] The hartebeest is the least migratory alcelaphine.[38] It also consumes the least amount of water and has the lowest metabolic rate among its tribal relatives.[38]

Parasites

Several parasites have been isolated from the hartebeest. A red hartebeest from the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park was found to host species of Cooperia, Impalaia nudicollis, Parabronema, and Trichostrongylus.[48] Nine Lichtenstein's hartebeest were sampled for Oestrinae. Larvae of Gedoelstia, Oestrus and Kirkioestrus species were isolated from the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses. A maximum of 252 larvae were found in the head of one animal, but no pathogenicity was found.[49] A red hartebeest in Gobabis (south-western Africa) was infected with long, thin worms. These were named Longistrongylus meyeri after their collector, T. Meyer, and proposed to be placed in the genus Longistrongylus.[50] In another case, a red hartebeest was infected with theileriosis due to parasites of Rhipicephalus evertsi and Theileria species.[51] Parasites in the hartebeest alternate between living off gazelles and wildebeest.[52] South of the Sahara, the hartebeest can be infested by Loewioestrus variolosus, Gedoelstia cristata and G. hassleri. The latter two species can cause serious diseases such as "bulging eye disease", which may lead to encephalitis.[53] In the 1960s, Robustostrongylus aferensis, an abomasal nematode, was discovered in a kongoni from Uganda.[54] Nematodes such as Haemonchus contortus, Trichostrongylus axei and Cooperia curticei; cestodes Moniezia expansa, Avitellina centripunctata, and Stilesia globipunctata; paramphistomes and Setaria labiato-papillosa were found in the digestive tract of a western hartebeest.[55]

Diet

Hartebeest are herbivores, and their diets consist mostly of grasses.[56] A study in the Nazinga Game Ranch in Burkina Faso determined that the hartebeest's skull structure eased the acquisition and chewing of highly fibrous foods. In comparison with the roan antelope, the hartebeest is better at procuring and chewing the scarce regrowth of perennial grasses at times when forage is least available. Generally comprising at least 80% of the hartebeest's diet, grasses make up over 95% of their food in the wet season, October to May. Jasminium kerstingii is part of the hartebeest's diet at the start of the rainy season. Between seasons, they mainly feed on the Culms grasses. They eat Hyparrhenia grasses and legumes in small amounts throughout the year.[57] The hartebeest can digest a larger quantity of food than other bovids.[58] In areas with scarce water, it can eat melons, roots, and tubers.[38]

In a study of grass selectivity among the wildebeest, zebra, and the Coke's hartebeest, the hartebeest showed the highest selectivity. All animals preferred Themeda triandra over Pennisetum mezianum and Digitaria macroblephara. More grass species were eaten in the dry season than in the wet season.[59]

Reproduction

Hartebeest mating occurs throughout the year. Peaks can be influenced by the availability of food.[56] Both males and females reach sexual maturity at one to two years of age. Reproduction depends on the subspecies and population at the time of mating.[36] Mating takes place in the territories defended by a single male, mostly in open areas on plateaus or ridges.[56] The males can fight fiercely for dominance.[43] The dominant male smells the female's genitals, and follows her if she is in oestrus. Sometimes a female holds out her tail slightly to signal her being in heat.[38] He will try to block the female's way. When she stops, she allows the male to mount her. Copulation occurs quickly, and is often repeated, sometimes twice or more a minute.[38] Any intruder at this time is chased away.[44] In large herds, the female mates with several males.[38] Gestation is about 240 days, after which a single calf is born. The newborn weighs about 9 kg (20 lb). Births take place in thickets, unlike wildebeest, which give birth in groups on the plains. The offspring is weaned at four months.[36] A male accompanies his mother for two and a half years, longer than other alcelaphines.[38]

Habitat and distribution

Hartebeest inhabit dry savannas and wooded grasslands,[11] often moving into more arid places after rainfall.[37] They are more tolerant of wooded areas than other alcelaphines, and are often found on the edge of woodlands.[56] They have been reported from altitudes on Mount Kenya up to 4,000 m (13,000 ft).[1] The red hartebeest is known to move across large areas, and females roam home ranges of over 1,000 km2 area, with male territories 200 km2 in size.[60] Females in the Nairobi National Park (Kenya) have been observed to have individual home ranges stretching over 3.7–5.5 km2, which are not particularly associated with any one female group. Average female home ranges are large enough to include even 20-30 male territories.[14]

The hartebeest was previously widespread in Africa. Their numbers have fallen drastically due to habitat destruction, hunting, human settlement, and competition for food with domestic cattle.[1][36] The size of hartebeest subspecies was correlated to habitat productivity and with rainfall.[61] The hartebeest is native to Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, the Ivory Coast, Kenya, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, and Uganda. It is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Lesotho, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Tunisia, and has been introduced into Swaziland and Zimbabwe.[1] The ranges of the hartebeest subspecies differ greatly from each other. The red hartebeest is very widespread after reintroduction to protected areas and ranches, and is the only hartebeest with an increasing population.[1] It occurs throughout most of southern Africa.[1] All the hartebeest subspecies, except the red hartebeest (increasing population)[18] and the Lichtenstein's hartebeest (stable population),[62] are decreasing in numbers, with three subspecies regarded as endangered: the Tora, Lelwel and Swayne's hartebeest. The Tora hartebeest is confined to Eritrea and Ethiopia, the Swayne's hartebeest to four protected areas, and the Lelwel hartebeest to a few protected areas.[1]

Status and conservation

Each hartebeest subspecies is listed under a different conservation status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, on the whole, the species hartebeest is classified as of Least Concern.[1] The red hartebeest is the most widespread, with increasing numbers after its reintroduction into protected and private areas.[1] Listed as Least Concern, its population is estimated to be over 130,000,[18] mostly in southern Africa.[60] The Bubal hartebeest has been declared extinct since 1994.[15] German explorer Heinrich Barth, in his works of 1857, cites firearms and European intrusion as among the reasons for the decrease in the Bubal hartebeest's population.[63] It was extinct in Tunisia by the late 19th century,[64] and the last one was shot between 1945 and 1954 in Algeria.[15]

The Coke's hartebeest is currently listed as of Least Concern. This subspecies has been greatly affected by habitat destruction, and about 42,000 Coke's hartebeest occur today in Mara, Serengeti National Park, and Tarangire National Park in Tanzania and Tsavo East National Park in Kenya. The population is decreasing, and 70% of the population lives in protected areas.[65] The western hartebeest is listed as Near Threatened; about 36,000 are known to exist. Over 95% of the population occurs in and around protected areas (such as the Comoé National Park), but numbers are declining even there.[66] The Lichtenstein's hartebeest is currently of Least Concern, and occurs in protected areas such as the Selous Game Reserve and in the wild in southern and western Tanzania and Zambia.[62]

The most threatened subspecies are the Tora, Lelwel, and Swayne's hartebeest. The Tora hartebeest is listed as Critically Endangered, with less than 250 mature specimens. They are possibly extinct in Sudan, and exist in lesser numbers in Eritrea and Ethiopia.[67] The Swayne's hartebeest is listed as Endangered, and is close to being Critically Endangered. A total of less than 600, of which the mature specimens number within 250, are confined to four major protected areas: the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary, Nechisar National Park, Awash National Park, and Mazie National Park.[68] The hartebeest in Senkele have to compete with the domestic animals of the Oromo people.[26] A study in the Nechisar National Park during 2009 and 2010 found a considerable increase in the livestock of the Oromos (49.9% and 56.5% increase during 2006 and 2010, respectively), illegal resource exploitation, and habitat loss as major threats to the Swayne's hartebeest populations there.[69] The Lelwel hartebeest is Endangered, and populations have declined greatly since the 1980s, when its population was over 285,000. It was then distributed mainly in the Central African Republic and southern Sudan.[65] Fewer than 70,000 individuals are left.[21] This hartebeest occurs in parts of southern Omo in Ethiopia.[70]

Uses

Hartebeest are popular game and trophy animals due to the highly regarded quality of their meat. Hunting travel packages for hartebeest are available online.[36] The hartebeest is easy to hunt due to its visibility.[44] In a study on the effect of place and gender on carcass characteristics, the average carcass weight of the male red hartebeest was 79.3 kg (175 lb) and that of females was 56 kg (123 lb). The meat of the animals from Qua-Qua region had the highest lipid content – 1.3 g (0.046 oz) per 100 g (3.5 oz) of meat. Negligible differences were found in the concentrations of individual fatty acids, amino acids, and minerals. The study considered hartebeest meat to be healthy, as the ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids was 0.78, slightly more than the recommended 0.7.[71]

A 2013 study analysed samples of game meat from South African supermarkets, wholesalers, and other outlets. It was found that some types of biltong labelled "kudu", "springbok", or "ostrich" were made of hartebeest. Of 146 samples, 100 were mislabelled, which revealed a great problem in meat labelling in South Africa.[72]

See Also

- Hirola, Hunter's hartebeest (Beatragus hunteri) of the same Alcelaphinae sub-family

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (2005). Mammal Species of the World : A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mares, M. A. (1999). Encyclopedia of Deserts. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-8061-3146-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Llewellyn, E.C. (1936). "Chapter XIV The Influence of South African Dutch or Afrikaans on the English Vocabulary". The Influence of Low Dutch on the English Vocabulary. London: Oxford University Press. p. 163.

- ↑ Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T. (2005). The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 649. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

- ↑ Harris, J.; Leakey, M. (2001). Lothagam: The Dawn of Humanity in Eastern Africa. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-231-11870-5.

- ↑ Flagstad, Ø.; Syvertsen, P. O.; Stenseth, N. C.; Jakobsen, K. S. (2001). "Environmental change and rates of evolution: the phylogeographic pattern within the hartebeest complex as related to climatic variation". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 268 (1468): 667–77. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1416. PMC 1088655. PMID 11321054.

- ↑ Berger, L. R.; Hilton-Barber, B. (2004). Field Guide to the Cradle of Humankind : Sterkfontein, Swartkrans, Kromdraai & Environs World Heritage Site (2nd rev. ed.). Cape Town: Struik. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-77007-065-3.

- ↑ Tsahar, E.; Izhaki, I.; Lev-Yadun, S.; Bar-Oz, G.; Hansen, D. M. (2009). "Distribution and extinction of ungulates during the Holocene of the xouthern Levant". PLoS ONE 4 (4): e5316. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005316.

- ↑ Wilson, D. E. (2005). Mammal Species of the World : A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. p. 675.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1181–3. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ↑ Groves, C.; Grubb, P. (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4214-0093-8.

- ↑ Matthee, C.; Robinson, TJ (1992). "Cytochrome b phylogeny of the family Bovidae: resolution within the Alcelaphini, Antilopini, Neotragini, and Tragelaphini". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 12 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1006/mpev.1998.0573. PMID 10222159.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Macdonald, D (1987). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 564–71. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus buselaphus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Mallon, D.P.; Kingswood, S.C. (2001). Antelopes: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. p. 25. ISBN 978-2-8317-0594-1.

- ↑ "Trophy Hunting Red Hartebeest". African Sky Safaris and Tours. African Sky. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus caama. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Kokwaro, J. O.; Johns, T. (1998). Luo Biological Dictionary. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. p. 217. ISBN 978-9966-46-841-3.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Lelwel Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI Online Record Book. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ Rafferty, J. P. (2010). Grazers (1st ed.). New York: Britannica Educational Publications. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-61530-465-3.

- ↑ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus lichtensteini. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Western Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI Online Record Book. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Swayne Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI Online Record Book. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Lewis, J. G.; Wilson, R. T. (1977). "The Plight of Swayne's Hartebeest". Oryx 13 (5): 491–4. doi:10.1017/S0030605300014551.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Hildyard, A. (2001). Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World. New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 674–5. ISBN 0-7614-7199-5.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Shurter, S.; Beetem, D. "Jackson's hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus jacksoni)" (PDF). Antelope & Giraffe Tag. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ East, R. (1999). African Antelope Database 1998. IUCN. p. 190. ISBN 978-2-8317-0477-7.

- ↑ P., Briggs; Roberts, A. (2010). Uganda : The Bradt Travel Guide. (6th ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-84162-309-2.

- ↑ Flagstad, Ø.; Syvertsen, P. O.; Stenseth, N. ChR.; Stacy, J. E.; Olsaker, I.; Røed, K. H.; Jakobsen, K. S. (2000). "Genetic variability in Swayne's hartebeest, an endangered antelope of Ethiopia". Conservation Biology 14 (1): 254–64. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98339.x.

- ↑ Robinson, T.J.; Morris, D.J.; Fairall, N. (1991). "Interspecific hybridization in the bovidae: Sterility of Alcelaphus buselaphus × Damaliscus dorcas F1 progeny". Biological Conservation 58 (3): 345–56. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(91)90100-N.

- ↑ "Kenya Highland Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI Online Record Book. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Ruxton, A. E.; Schwarz, E. (2010). "On hybrid hartebeests and on the distribution of tbe Alcelaphus buselaphus group". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 99 (3): 567–83. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07706.x.

- ↑ "Neumann's Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI Online Book Record. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 36.7 36.8 Batty, K. "Alcelaphus buselaphus". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 "Hartebeest fact file". Wildscreen. Arkive. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 38.8 38.9 38.10 38.11 Estes, R. D. (2004). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals : Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (4th ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 133–42. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Firestone, M. (2009). Watching Wildlife : Southern Africa ; South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia (2nd ed.). Footscray: Lonely Planet. pp. 228–9. ISBN 978-1-74104-210-8.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Coke's Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI: Online Record Book. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Lichtenstein Hartebeest". Safari Club International. SCI: Online Record Book. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Capellini, I.; Gosling, L. M. (2006). "The evolution of fighting structures in hartebeest". Evolutionary Ecology Research 8: 997–1011.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Capellini, I. (2007). "Dimorphism in the hartebeest". Sex, Size and Gender Roles: 124–32. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199208784.003.0014. ISBN 978-0-19-920878-4.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Kingdon, J. (1989). East African Mammals : An Atlas of Evolution in Africa (Volume 3, Part D:Bovids). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-43725-6.

- ↑ "FAIL LAB Episode One: Evolution, Featuring Professor Theodore Garland, Jr.". youtube.com.

- ↑ Schaller, G. B. (1976). The Serengeti Lion : A Study of Predator-Prey Relations (Pbk. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 461–5. ISBN 978-0-226-73640-2.

- ↑ Verlinden, A. (1998). "Seasonal movement patterns of some ungulates in the Kalahari ecosystem of Botswana between 1990 and 1995". African Journal of Ecology 36 (2): 117–28. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2028.1998.00112.x.

- ↑ Boomker, J.; Horak, I.G.; De Vos, V. (1986). "The helminth parasites of various artiodactylids from some South African nature reserves". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 53 (2): 93–102. PMID 3725333.

- ↑ Howard, G. W. (1977). "Prevalence of nasal bots (Diptera: Oestridiae) in some Zambian hartebeest". Journal of Wildlife Diseases 13 (4): 400–4. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-13.4.400.

- ↑ le Roux, P. L. (1931). "On Longistrongylus meyeri gen. and sp. nov., a trichostrongyle parasitizing the Red Hartebeest Bubalis caama". Journal of Helminthology 9 (3): 141. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00030376.

- ↑ Spitalska, E.; Riddell, M.; Heyne, H.; Sparagano, O. A. E. (1995). "Prevalence of theileriosis in Red Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus caama) in Namibia". Parasitology Research 97 (1): 77–9. doi:10.1007/s00436-005-1390-y. ISSN 1432-1955. PMID 15986252.

- ↑ Pester, F. R. N.; Laurence, B. R. (1974). "The parasite load of some African game animals". Journal of Zoology 174 (3): 397–406. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1974.tb03167.x.

- ↑ Spinage, C. A. (2012). African Ecology - Benchmarks and Historical Perspectives. Berlin: Springer. p. 1176. ISBN 978-3-642-22872-8.

- ↑ Hoberg, E. P.; Abrams, A.; Pilitt, P. A. (2009). "Robustostrongylus aferensis gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) in kob (Kobus kob) and hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus jacksoni) (Artiodactyla) from Sub-Saharan Africa, with further ruminations on the Ostertagiinae". Journal of Parasitology 95 (3): 702–717. doi:10.1645/GE-1859.1. ISSN 1937-2345.

- ↑ Belem, A. M. G.; Bakoné, É. U. (2009). "Gastro-intestinal parasites of antelopes and buffaloes (Syncerus caffer brachyceros) from the Nazinga game ranch in Burkina Faso". Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement 13 (4): 493–8. ISSN 1370-6233.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 "Hartebeest". African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Schuette, J. R.; Leslie, D. M.; Lochmiller, R. L.; Jenks, J. A. (1998). "Diets of hartebeest and roan antelope in Burkina Faso: support of the long-faced hypothesis". Journal of Mammalogy 79 (2): 426–36. doi:10.2307/1382973.

- ↑ Murray, M. G. (1993). "Comparative nutrition of wildebeest, hartebeest and topi in the Serengeti". African Journal of Ecology 31 (2): 172–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1993.tb00530.x.

- ↑ Casebeer, R. L.; Koss, G. G. (1970). "Food habits of wildebeest, zebra, hartebeest and cattle in Kenya Masailand". African Journal of Ecology 8 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1970.tb00827.x.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Mills, G.; Hes, L. (1997). The Complete Book of Southern African Mammals. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-947430-55-9.

- ↑ Capellini, I.; Gosling, L. M. (2007). "Habitat primary production and the evolution of body size within the hartebeest clade". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 92 (3): 431–40. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00883.x.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus lichtensteinii. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Yadav, P.R. (2004). Vanishing and Endangered Species. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House. pp. 139–40. ISBN 978-81-7141-776-6.

- ↑ Mallon, D.P.; Kingswood, S.C. (2001). Antelopes: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-8317-0594-1.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 East, R.; Group, the IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist (1999). African Antelope Database 1998. Gland, Switzerland: The IUCN Species Survival Commission. ISBN 978-2-8317-0477-7.

- ↑ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus major. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus tora. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). Alcelaphus buselaphus swaynei. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Datiko, D.; Bekele, A. (2011). "Population status and human impact on the endangered Swayne’s hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus swaynei) in Nechisar Plains, Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia". African Journal of Ecology 49 (3): 311–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2011.01266.x.

- ↑ Briggs, P. (2013). Ethiopia (6th ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84162-414-3.

- ↑ Hoffman, L. C.; Smit, K.; Muller, N. (2010). "Chemical characteristics of red hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus caama) meat". South African Journal of Animal Science 40 (3): 221–8. doi:10.4314/sajas.v40i3.6.

- ↑ BioMed Central (2013). "Problems with identifying meat? The answer is to check the barcode". BioMed Central. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

External links

-

Media related to Alcelaphus buselaphus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alcelaphus buselaphus at Wikimedia Commons -

Data related to Alcelaphus buselaphus at Wikispecies

Data related to Alcelaphus buselaphus at Wikispecies