Harold Heslop

Harold Heslop (1898–1983) was an English writer.

Biography

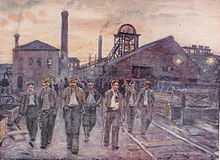

Harold Heslop, coalminer and author, was born on 1 October 1898 in the village of Hunwick, near Bishop Auckland, County Durham, to William Heslop, coalminer, and his wife, Isabel, née Whitfield. The Heslops had been miners for several generations. Heslop attended King James I Grammar School in Bishop Auckland on a scholarship until he was thirteen, then the family moved to Boulby on the north Yorkshire coast. Because this was too far from the nearest grammar school, Heslop began working underground at Boulby ironstone mine, where his father was now the manager.[1] Shortly after this his mother died, and then his father remarried and the family moved to Northumberland. Soon after this Heslop moved to South Shields and started work at Harton colliery, where he remained for eleven years.[1]

After World War I he was active in left-wing politics as secretary of a local Independent Labour Party branch and represented the miners of Harton colliery on the council of the Durham Miners' Association.[1] Then in 1923 he won a scholarship to study at the Central Labour College, a British higher education institution supported by trade unions, in London which he attended 1924-26.[2][3] On 27 March 1926 Harold Heslop married Phyllis Hannah Varndell who clerk at Selfridges and whose family were active in left wing politics.[1] The same year Heslop's first novel Goaf was published, but it was in a Russian translation as Pod vlastu uglya and did not appear in England until 1934. This novel, about mining in northern England, apparently "sold half a million copies in Russia and made Heslop's name there", though he was only able to transfer a small part of his royalties to England.[4]

Heslop returned to at Harton in 1926, where he unsuccessfully contested a seat on the South Shields Town Council for the Labour Party, sponsored by the Miners Lodge,[5] but because of the contraction of the coal industry he became unemployed and the Heslops moved to London, where he worked at various things. Heslop's political activity included working for the British Communist Party's general secretary, Harry Pollitt against Ramsay MacDonald for the Seaham division of Durham in the 1929 election.[1] In 1929 he also published his first novel in England, The Gate of a Strange Field, which was about the General Strike of 1926. The following year another novel Journey Beyond, about unemployment in London, was published. Also in 1930 he was invited to attended the Second Plenum of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Literature in Russia.[6] Subsequently four of his novels were published in the Soviet Union, "including Red Earth (1931), a utopian novel about a successful revolution in Britain which was never published in the UK".[7] He also worked in London for the Soviet trading mission and later Intourist.[1] In 1934 his novel Goaf appeared in an English version, as well this year Heslop also published a detective novel, The Crime of Peter Ropner. In 1935 Last Cage Down was published, and in 1937, under the pseudonym Lincoln J. White, Abdication, a study written with Bob Ellis about the abdication crisis, which sold over 40,000 copies.[1]

During the war the Heslops evacuated to Taunton in Somerset, where he worked on his most successful novel in Britain, The Earth Beneath which was published in 1946 and sold 9000 copies, but although he continued to write this was his last novel.[1] While in Somerset Heslop joined the Labour Party and in 1948 he won a seat on the Taunton Town Council; however, he failed in a later attempt to become a Labour Member of Parliament for North Devon.[4] Some years after his death in 1983 Out of the Old Earth appeared in 1994, which was based on the manuscript of Heslop's Autobiography.[8]

Works

Harold Heslop's literary career began in 1926 with the Russian version of Goaf and then, starting with The Gate of a Strange Field, Heslop published five novels in England between 1929 and 1946, while his autobiography, Out of the Old Earth, was published posthumously. Harold Heslops's first novel published in England, The Gate of a Strange Field is about the General Strike of 1926, which he had witnessed in London.[9] The novel took its title from a phrase in H. G. Wells' novel Meanwhile.[9] It was generally well reviewed, The New York Times, for example, commented, that "the sheer honesty of the book makes it powerful", but the critic of The Communist Review found it "full of cliches" and "unending literary jargon"[10] A more recent discussion, however, found that "the most interesting feature of the novel ... is not the study of the labour movement but of the hero's sexual repression".[11]

Heslop's next novel Journey Beyond (1930) deals with the subject of unemployment. While Heslop's biography might suggest that he was a committed communist this work is condemned as "tending towards social fascism" in an article in the Soviet sponsored International Literature.[12] In 1934 the original English version of Heslop's novel Goaf was published, as well as The Crime of Peter Ropner, which is an "attempt at a crime novel from a left-wing perspective".[13] Famous crime novelist Dorothy L. Sayers reviewed it, and while disliking much about it, found that it had "a crude and sordid power".[14]Last Cage Down, set in a coal-field, appeared in 1935, and seems to have been an attempt to answer the earlier criticism of Heslop's commitment to communist ideals. H. Gustav Klaus comments, "It is the one work which echoes the Communist line most unequivocally".[15] However, two left-wing journals, The Daily Worker and The Left Review, gave it "only cautious praise".[16]

It was over ten years before Heslop published another novel, which was to be his last. According to one critic Harold Heslop in The Earth Beneath, drawing "From his own experience as a miner (and from stories of his father and grandfather ...) ....has fashioned a gripping, passionate a gripping, passionate novel of the English coal miners".[17] Andy Croft also has praise and describes it as "a rich and scholarly history of work and family life in the Durham coalfield in the nineteenth century".[18]

Harold Heslop died 10 November 1983. Over ten years after his death his autobiography Out of the Old Earth (1994) was published, which has been described, as a "rich recollections of childhood in the coalfield, [and] portraits of his family [along with a] fine descriptions of working life above and below ground".[19]

Bibliography

- Published works

- Pod vlastu uglya, translation by Zinaida Vengerova-Minskaia. Moscow: Priboj, 1926.[20]

- The Gate of a Strange Field. London: Brentano, 1929; New York:Appleton, 1929. There was also a Russiasn translation.[21]

- Journey Beyond. London: H. Shaylor, 1930.

- The Crime of Peter Ropner. London: Fortune Press, 1934.

- Goaf. London: Fortune Press, 1934; published first in 1926 in Russia as Pod vlastu uglya (Under the Sway of Coal)[22]

- Last Cage Down. London: Wishart, 1935; London : Wishart, 1984.

- The Abdication of Edward VIII: A Record With All the Published Documents. (Published under the pseudonym of J. Lincoln White, this was a joint work with Robert Ellis). London: Routledge, 1936.[20]

- The Earth Beneath. London: Boardman, 1946; New York: J. Day Co., 1947.

- Out of the Old Earth (autobiography), ed. Andy Croft and Graeme Rigby. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe, 1994.

- Heslop also published two penny-pamphlets in 1927 attacking the anti-trade union sentiments of the local Northern Press newspapers, Who are your Masters? and Who Are Your Masters Now? No.2. The Northern Press, The Runcimans, and South Shields. South Shields: Harold Heslop,1927,[1] and regular reviews for The Worker c.1929-1932. Heslop also published in other left wing journals such as Left Review, and contributed "short stories and literary criticism to a range of publications, from Labour Monthly to Plebs, the Communist to International Review ".[23]

- Secondary sources

- Eichler, Tanja, "Women characters in Harold Heslop's Last Cage Down and Lewis Jones' Cwmardy". In Behrend, Hanna and Neubert, Isolde (eds), Working-class and feminist literature in Britain and Ireland in the 20th century proceedings of the 3rd conference in Berlin, 20 to 22 March 1989. Berlin: Humboldt UP, 1990. 2 vols. (Gesellschaftswissenschaften Studien.) [1997:851997:85]. pp. 17–24.

- Andy Croft, Red Letter Days: British Fiction in the 1930s. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990) and

- "Introduction" to Out of the Old Earth by Harold Heslop, ed. Andy Croft and Graeme Rigby. Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 1994 and

- "Heslop, Harold (1898–1983)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. accessed 30 Oct 2012.

- E. Elistratova, "The work of Harold Heslop", International Literature, 1 (1932), pp. 99–102.

- Ian Haywood, Working-Class Fiction from Chartism to Trainspotting. Plymouth: Northcote House, 1997.

- John Fordham, "A Strange Field: Region and Class in the Novels of Harold Heslop" in Intermodernism: Literary Culture in Mid-Twentieth-Century Britain, ed. Kristin Bluemel. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

- H. Gustav Klaus, "Harold Heslop: miner novelist", The Literature of Labour: Two Hundred Years of Working-Class Writing". Brighton: Harvester Press, 1985.

- Alick West, "Harold Heslop and The Gate of a Strange Field", Crisis and Criticism. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1937.

See also

- Social novel

- Proletarian literature

- Welsh literature in English: for Welsh mining novelists

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Andy Croft, "Heslop, Harold (1898–1983)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. accessed 30 Oct 2012

- ↑ "A Summary Description of the Papers of the Central Labour College: North Eastern Branch". University of Warwick. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "New Labour College At Oxford". The Times. 3 August 1909. p. 4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 H. Gustav Klaus, The Literature of Labour. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1985, p.105.

- ↑ 97

- ↑ H. Gustav Klaus, The Literature of Labour. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1985, pp. 96-101.

- ↑ Andy Croft, "Heslop, Harold (1898–1983)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. accessed 30 Oct 2012; E. Elistratova, ‘The Work of Harold Heslop’, International Literature, 1 (1932), p.99.

- ↑ Durham University Library Special Collections Catalogue: Harold Heslop Papers. Reference code: GB-0033-HES.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 John Lucas, The Radical Twenties. Rutgers University Press 1999. ISBN 978-0813526829 (pp. 237-38).

- ↑ The New York Times (Early City Edition); 4 Aug 1929, p.7; quoted in H. Gustav Klaus, The Literature of Labour, p.97.

- ↑ Ian Haywood, Working-Class Fiction from Chartism to Trainspotting. Plymouth: Northcote House, 1997. p.44.

- ↑ E. Elistratova, ‘The Work of Harold Heslop’, International Literature, p.100

- ↑ H. Gustav Klaus, The Literature of Labour, p.102.

- ↑ H. Gustav Klaus, The Literature of Labour, pp.102-3.

- ↑ 'The Literature of Labour, p.103.

- ↑ Andy Croft, "Introduction" to Last Cage Down by Harold Heslop. London: Wishart, 1984, p.xii.

- ↑ New York Times, 2 November 1947.

- ↑ Andy Croft, "Heslop, Harold (1898–1983)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ↑ Alan Myers Literary Guide

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 H. Gustav Klaus, The Literature of Labour. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1985, p.95.

- ↑ The Literature of Labour, p.97

- ↑ E. Elistratova, ‘The Work of Harold Heslop’, International Literature, 1 (1932), p.99.

- ↑ Andy Croft, "Introduction" to Last Cage Down by Harold Heslop. London: Wishart Books 1994, p.xi.