Harmonic coordinate condition

The harmonic coordinate condition is one of several coordinate conditions in general relativity, which make it possible to solve the Einstein field equations. A coordinate system is said to satisfy the harmonic coordinate condition if each of the coordinate functions xα (regarded as scalar fields) satisfies d'Alembert's equation. The parallel notion of a harmonic coordinate system in Riemannian geometry is a coordinate system whose coordinate functions satisfy Laplace's equation. Since d'Alembert's equation is the generalization of Laplace's equation to space-time, its solutions are also called "harmonic".

Motivation

The laws of physics can be expressed in a generally invariant form. In other words, the real world does not care about our coordinate systems. However, for us to be able to solve the equations, we must fix upon a particular coordinate system. A coordinate condition selects one (or a smaller set of) such coordinate system(s). The Cartesian coordinates used in special relativity satisfy d'Alembert's equation, so a harmonic coordinate system is the closest approximation available in general relativity to an inertial frame of reference in special relativity.

Derivation

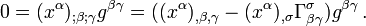

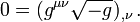

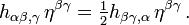

In general relativity, we have to use the covariant derivative instead of the partial derivative in d'Alembert's equation, so we get:

Since the coordinate xα is not actually a scalar, this is not a tensor equation. That is, it is not generally invariant. But coordinate conditions must not be generally invariant because they are supposed to pick out (only work for) certain coordinate systems and not others. Since the partial derivative of a coordinate is the Kronecker delta, we get:

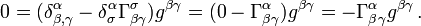

And thus, dropping the minus sign, we get the harmonic coordinate condition (also known as the de Donder gauge [1]):

This condition is especially useful when working with gravitational waves.

Alternative form

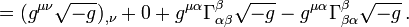

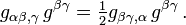

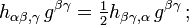

Consider the covariant derivative of the density of the reciprocal of the metric tensor:

The last term  emerges because

emerges because  is not an invariant scalar, and so its covariant derivative is not the same as its ordinary derivative. Rather,

is not an invariant scalar, and so its covariant derivative is not the same as its ordinary derivative. Rather,  because

because  , while

, while

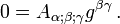

Contracting ν with ρ and applying the harmonic coordinate condition to the second term, we get:

Thus, we get that an alternative way of expressing the harmonic coordinate condition is:

More variant forms

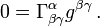

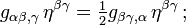

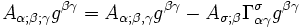

If one expresses the Christoffel symbol in terms of the metric tensor, one gets

Discarding the factor of  and rearranging some indices and terms, one gets

and rearranging some indices and terms, one gets

In the context of linearized gravity, this is indistinguishable from these additional forms:

However, the last two are a different coordinate condition when you go to the second order in h.

Effect on the wave equation

For example, consider the wave equation applied to the electromagnetic vector potential:

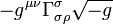

Let us evaluate the right hand side:

Using the harmonic coordinate condition we can eliminate the right-most term and then continue evaluation as follows:

See also

- Christoffel symbols

- Covariant derivative

- Gauge theory

- General relativity

- General covariance

- Kronecker delta

- Laplace's equation

- Laplace operator

- Ricci calculus

- Wave equation

References

- ↑ [John Stewart (1991), "Advanced General Relativity", Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-44946-4 ]

- P.A.M.Dirac (1975), General Theory of Relativity, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01146-X, chapter 22