Hans Reck

| Hans Gottfried Reck | |

|---|---|

Hans Reck | |

| Born | 24 January 1886 |

| Died | 4 August 1937 |

| Occupation | Paleontologist |

| Known for | 1913 discovery of Olduvai skeleton |

Hans Gottfried Reck (24 January 1886 – 4 August 1937) was a German volcanologist and paleontologist. In 1913 he was the first to discover the ancient skeleton of a human in the Olduvai Gorge, in what is now Tanzania. He collaborated with Louis Leakey in a return expedition to the site in 1931.

Birth and education

Reck was born into a military family in Würzburg, Bavaria on 24 January 1886. He attended the universities of Wurzburg and Berlin, where he studied natural history and became deeply interested in volcanoes.[1]

Iceland

In the summer of 1907 the geologist Walther von Knebel, a friend and fellow student of Reck's, disappeared during a field trip in Iceland.[1] Hans Reck was charged with determining what had happened, and set out in June 1908 with two local guides and his fiance, Ina von Grumbkow. The party traveled 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) on horseback in eleven weeks.[2] Reck and the Icelander Sigurður Sumarliðason were the first people ever to reach the summit of the Herðubreið volcano, 1,060 metres (3,480 ft) above the surrounding plain.[3]

Reck climbed down to the edge of what would later be called Lake Knebel (now Öskjuvatn), a boiling sulphurous lake where von Knebel's death had been reported, but found no remains.[4] However, they concluded that von Knebel had died in an accidental drowning when his boat overturned. Reck used what he learned about volcanoes on this expedition in his doctoral dissertation. He graduated from the University of Munich in November 1910 and took up a post in the Berlin Museum of Natural History.[2]

First East African Expedition

Hans Reck studied at University College London, then became a private lecturer at the Museum of Natural History. He married Ina von Grumbkow in February 1912. She was considerably older than him, having been born in September 1872, and was a strong and capable woman. The Recks were assigned to follow-up the 1911 expedition that had made a large collection of fossils at Tendaguru in German East Africa (now Tanzania).[2] They reached Tendaguru in June 1912, rebuilt the camp and quickly settled into a routine of quarrying to collect dinosaur bones, helped by a large workforce of local people.[5] Great quantities of rubble were excavated to uncover the bones, which lay about 4 metres (13 ft) below the surface. These included the well-preserved skeletons of two stegosaurs, an armor-plated dinosaur.[6]

Reck found an early Iron Age site at Engaruka, where a stream from the Ngorongoro hills plunges down the western wall of the Gregory Rift at a point between Lake Natron and Lake Manyara, and published a description in 1913.[7] Also in 1913, Reck made an ascent of the 2,960 metres (9,710 ft) Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano in the Gregory Rift, about 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) south of Lake Natron He was the third geologist to do so. Oldoinyo Lengai is the only active carbonatite volcano in the world. In 1914 Reck published a comprehensive report that summarized all that was known about this volcano so far, from his and earlier expeditions. It described the geographic position of the volcano, history of explorations, geomorphological studies and gave a detailed account of the crater region, accompanied by photographs.[8]

In 1911 Wilhelm Kattwinkel, a German entomologist, had found interesting fossils in a ravine on the borders of the Serengeti Plains which turned out to contain the remains of a prehistoric three-toed horse. He gave the site the name "Oldoway", later to be changed by the British to Olduvai.[9][lower-alpha 1] In October 1913 Reck managed to find the site again, despite vague directions. He spent the next few months making a geological survey and collecting over 1,700 fossils.[9] The site was unusual in being made of distinctive layers of different-colored lavas and ash. Although there was no way at that time of accurately dating the layers, they did indicate the relative age of the deposits.[10]

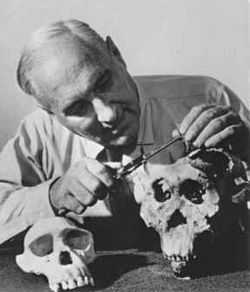

In December 1913 one of the workmen found a bone protruding from one of the oldest layers, Bed II, at a level where extinct animals from the Pleistocene had been found. He started to excavate, then told Reck of his find. Reck directed the excavation. The workers used hammers and chisels to excavate a human skeleton with modern anatomy that was embedded in a block of sedimentary rock. Reck examined the surrounding rocks carefully, but found no sign of disturbance that could indicate a burial at some later data.[11] Reck took the skull back to Berlin in March 1914, and published an article in which he speculated that the skeleton was of a man from 150,000 years ago, far earlier than had been previously considered for the origin of man. The announcement caused a considerable stir, although many people dismissed Reck's claims, saying it must be a recent burial.[12]

World War I

Reck returned to East Africa to work for the government as a geologist after the outbreak of World War I in July 1914.[12] In June 1915 Reck discovered more Pleistocene fossils at a site close to Minjonjo, which he considered to have a similar age to those he had found at Olduvai. In September he returned to this site, and dispatched two loads of fossils to the Ufiome base.[13] In 1915-1916 Reck excavated burial mounds in the Ngorongoro crater.[14] The mounds held stone bowls and beads buried with the skeletons, but Reck did not identify any Stone Age tools.[15]

In April 1916 a force of British and Belgian troops advanced from the west. Ina escaped and Hans Reck volunteered and was appointed commander of a small squad of troops.[13] In June 1916 Reck turned over his field notes, personal valuables and the collection of pterosaur bones from Tendaguru to a Swiss railway engineer, who promised to take them to Switzerland if possible.[16] In late August 1916 Reck was ordered to move into the Uluguru Mountains. Inconclusive fighting continued for the rest of that year, with the allies handicapped by demolitions and suffering considerably from harsh conditions, disease and lack of supplies.[16] Starting in 1917 the allies gradually began to gain the ascendancy, and by November 1917 the last Germans capable of leaving the country evacuated it for Portuguese East Africa. Reck was not with them, having been taken prisoner late in 1917.[17]

Later career

After the war, the British took over German East Africa, now named Tanganyika. Hans Reck was released from internment in Africa and returned to the Museum to resume his work as an assistant there.[18] In 1927 the anthropologist Louis Leakey visited Munich to examine the Oldoway Man, and he returned in 1929 for a further study. In his opinion the skeleton was not nearly as old as Reck thought, but was probably about the same age as stone age skeletons from around 20,000 years ago that Leakey had found in Kenya. Leakey found the rock and fossil collection from Olduvai was also similar to his Kenya finds. He thought some could be tools, and suggested other tools might be found at Olduvai. Reck disagreed, saying he had searched for tools and found none in 1913.[19]

Leakey invited Reck to accompany him on a fresh expedition to Olduvai, which Reck gladly accepted. The expedition reached Olduvai in September 1931. Leakey soon found a hand-axe made from volcanic rock, not from the flint that Reck had been searching for, winning a large wager the two men had made. Within the next four days seventy seven hand axes were discovered. Leakey examined the location where Reck had found the skeleton, and quickly came to accept Reck's estimate of its age.[20] Leakey, Reck and Arthur Hopwood, another paleontologist, drafted a letter to Nature that stated that the question of the age of Olduvai Man was settled, and was nearly half a million years, and Leakey made a quick return trip to Nairobi to dispatch this and other letters announcing the find.[21][lower-alpha 2]

Reck had lost all his notes on Olduvai during World War I, but published a book of his first expedition in 1933 called The Ravine of Primeval Man.[23] Hans Reck undertook a major study of the Santorini islands in the Aegean in 1936, working with Neuman van Padang and others. The islands form the rim of a caldera. The detailed 1936 work was a major contribution to understanding the evolution of the Santorini volcano and its relation to the geology of the region.[24]

Reck was planning to prepare a detailed report on the 1913 and 1931 Olduvai findings, but first left on an expedition to Portuguese East Africa.[25] Reck had a congenital heart problem, although this had not stopped him in his many expeditions.[26] He died of a heart attack in Lourenço Marques in August 1937.[27] Hans Reck was not just a vulcanologist and paleontologist, but was an enthusiastic collector of Arab art and a skilled pianist.[27] Apart from the skull, most of the skeleton found by Reck at Olduvai was destroyed by bombs during World War II (1939–1945).[28] After the war ended his widow attempted unsuccessfully to locate his field notes, contained in many volumes, but they could not be found.[25]

Bibliography

- Die Hegau-Vulkane (The Hegau volcanoes). Berlin. 1923.

- Oldoway. Die Schlucht des Urmenschen (Olduvai. The gorge of primitive man). Leipzig. 1933.

- Santorin. Der Werdegang eines Inselvulkans und sein Ausbruch (Santorini. The story of an island volcano and its eruption). Berlin. 1936.

Notes and references

- ↑ It seems that Kattwinkel gestured at the ravine and asked the local Maasai people what it was called. They misunderstood his question and answered "oldupai", the Maasai word for the wild sisal plants that were growing there. Kattwinkel recorded the name as "Oldoway". When Reck was later looking for a place called Oldoway, naturally nobody had heard of it.[9]

- ↑ Modern methods of dating give an age of between 1.15 and 1.7 years for the level in which Reck's Olduvai Gorge skeleton was found.[11] However, soon after the 1931 expedition it was established that the skeleton was far more recent than the deposit in which it was found, having collapsed into this level due to a geological fault.[22]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Maier 2003, p. 86.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Maier 2003, p. 87.

- ↑ Simmonds 1999, p. 323.

- ↑ Martill et al 2010, p. 141.

- ↑ Maier 2003, p. 88.

- ↑ Maier 2003, p. 89.

- ↑ Oliver & Fagan 1975, p. 87.

- ↑ Möckel 2005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Meredith 2011, p. 14.

- ↑ Meredith 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cremo 2010, p. 140.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Meredith 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Maier 2003, p. 109.

- ↑ Ucko & Shennan 2006, p. 151.

- ↑ Ben-Jochannan 1972, p. 93.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Maier 2003, p. 111.

- ↑ Maier 2003, p. 112.

- ↑ Maier 2003, p. 150.

- ↑ Meredith 2011, p. 32.

- ↑ Meredith 2011, p. 33.

- ↑ Morell 1996, p. 59.

- ↑ Kuper 1996, p. 40.

- ↑ Meredith 2011.

- ↑ Fouqué & McBirney 1998, p. 453.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Leakey 1965, p. 1.

- ↑ Martill et al 2010, p. 142.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Maier 2003, p. 259.

- ↑ Cremo 2010, p. 187.

Sources

- Ben-Jochannan, Yosef (1972). Black man of the Nile and his family. Black Classic Press. ISBN 0-933121-26-1.

- Cremo, Michael A. (2010). Forbidden Archeologist: The Atlantis Rising Magazine Columns of Michael A. Cremo. Torchlight Publishing. ISBN 0-89213-337-6.

- Fouqué, Ferdinand; McBirney, Alexander R. (1998). Santorini and its eruptions. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-5614-0.

- Kuper, Adam (1996). The chosen primate: human nature and cultural diversity. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-12826-5.

- Leakey, L. S. B. (1965). Olduvai Gorge. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-10517-X.

- Maier, Gerhard (2003). African dinosaurs unearthed: the Tendaguru expeditions. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34214-7.

- Moody, R. T. J.; Martill, M. D.; Buffetaut, E.; Naish, D.; Martill, D. M. (2010). Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society. ISBN 1-86239-311-7.

- Meredith, Martin (2011). Born in Africa: The Quest for the Origins of Human Life. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-663-2.

- Möckel, Frank (December 2005). "Die Geschichte der Erforschung des Vulkans Oldoinyo Lengai, Tansania (The history of exploration Oldoinyo Lengai volcano, Tanzania)" (in German). Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- Morell, Virginia (1996). Ancestral passions: the Leakey family and the quest for humankind's beginnings. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82470-1.

- Oliver, Roland Anthony; Fagan, Brian M. (1975). Africa in the Iron Age, c500 B.C. to A.D. 1400. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09900-5.

- Simmonds, Jane (1999). Iceland. Langenscheidt Publishing Group. ISBN 0-88729-176-7.

- Ucko, Peter J.; Shennan, Stephen (2006). A future for archaeology: the past in the present. Routledge. ISBN 1-84472-126-4.