Handshaking lemma

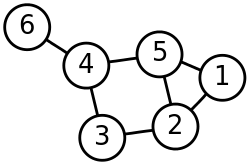

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, the handshaking lemma is the statement that every finite undirected graph has an even number of vertices with odd degree (the number of edges touching the vertex). In more colloquial terms, in a party of people some of whom shake hands, an even number of people must have shaken an odd number of other people's hands.

The handshaking lemma is a consequence of the degree sum formula (also sometimes called the handshaking lemma),

for a graph with vertex set V and edge set E. Both results were proven by Leonhard Euler (1736) in his famous paper on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg that began the study of graph theory.

The vertices of odd degree in a graph are sometimes called odd nodes or odd vertices; in this terminology, the handshaking lemma can be restated as the statement that every graph has an even number of odd nodes.

Proof

Euler's proof of the degree sum formula uses the technique of double counting: he counts the number of incident pairs (v,e) where e is an edge and vertex v is one of its endpoints, in two different ways. Vertex v belongs to deg(v) pairs, where deg(v) (the degree of v) is the number of edges incident to it. Therefore the number of incident pairs is the sum of the degrees. However, each edge in the graph belongs to exactly two incident pairs, one for each of its endpoints; therefore, the number of incident pairs is 2|E|. Since these two formulas count the same set of objects, they must have equal values.

In a sum of integers, the parity of the sum is not affected by the even terms in the sum; the overall sum is even when there is an even number of odd terms, and odd when there is an odd number of odd terms. Since one side of the degree sum formula is the even number 2|E|, the sum on the other side must have an even number of odd terms; that is, there must be an even number of odd-degree vertices.

Alternatively, it is possible to use mathematical induction to prove that the number of odd-degree vertices is even, by removing one edge at a time from a given graph and using a case analysis on the degrees of its endpoints to determine the effect of this removal on the parity of the number of odd-degree vertices.

Regular graphs

The degree sum formula implies that every r-regular graph with n vertices has nr/2 edges.[1] In particular, if r is odd then the number of edges must be divisible by r.

Infinite graphs

The handshaking lemma does not apply to infinite graphs, even when they have only a finite number of odd-degree vertices. For instance, an infinite path graph with one endpoint has only a single odd-degree vertex rather than having an even number of such vertices.

Exchange graphs

Several combinatorial structures listed by Cameron & Edmonds (1999) may be shown to be even in number by relating them to the odd vertices in an appropriate "exchange graph".

For instance, as C. A. B. Smith proved, in any cubic graph G there must be an even number of Hamiltonian cycles through any fixed edge uv; Thomason (1978) used a proof based on the handshaking lemma to extend this result to graphs G in which all vertices have odd degree. Thomason defines an exchange graph H, the vertices of which are in one-to-one correspondence with the Hamiltonian paths beginning at u and continuing through v. Two such paths p1 and p2 are connected by an edge in H if one may obtain p2 by adding a new edge to the end of p1 and removing another edge from the middle of p1; this is a symmetric relation, so H is an undirected graph. If path p ends at vertex w, then the vertex corresponding to p in H has degree equal to the number of ways that p may be extended by an edge that does not connect back to u; that is, the degree of this vertex in H is either deg(w) − 1 (an even number) if p does not form part of a Hamiltonian cycle through uv, or deg(w) − 2 (an odd number) if p is part of a Hamiltonian cycle through uv. Since H has an even number of odd vertices, G must have an even number of Hamiltonian cycles through uv.

Computational complexity

In connection with the exchange graph method for proving the existence of combinatorial structures, it is of interest to ask how efficiently these structures may be found. For instance, suppose one is given as input a Hamiltonian cycle in a cubic graph; it follows from Smith's theorem that there exists a second cycle. How quickly can this second cycle be found? Papadimitriou (1994) investigated the computational complexity of questions such as this, or more generally of finding a second odd-degree vertex when one is given a single odd vertex in a large implicitly-defined graph. He defined the complexity class PPA to encapsulate problems such as this one; a closely related class defined on directed graphs, PPAD, has attracted significant attention in algorithmic game theory because computing a Nash equilibrium is computationally equivalent to the hardest problems in this class.[2]

Other applications

The handshaking lemma is also used in proofs of Sperner's lemma and of the piecewise linear case of the mountain climbing problem.

Notes

- ↑ Aldous, Joan M.; Wilson, Robin J. (2000), "Theorem 2.2", Graphs and Applications: an Introductory Approach, Undergraduate Mathematics Series, The Open University, Springer-Verlag, p. 44, ISBN 978-1-85233-259-4

- ↑ Chen, Xi; Deng, Xiaotie (2006), "Settling the complexity of two-player Nash equilibrium", Proc. 47th Symp. Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 261–271, doi:10.1109/FOCS.2006.69, ECCC TR05-140

References

- Cameron, Kathie; Edmonds, Jack (1999), "Some graphic uses of an even number of odd nodes", Annales de l'Institut Fourier 49 (3): 815–827, doi:10.5802/aif.1694, MR 1703426.

- Euler, L. (1736), "Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis", Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae 8: 128–140. Reprinted and translated in Biggs, N. L.; Lloyd, E. K.; Wilson, R. J. (1976), Graph Theory 1736–1936, Oxford University Press.

- Papadimitriou, Christos H. (1994), "On the complexity of the parity argument and other inefficient proofs of existence", Journal of Computer and System Sciences 48 (3): 498–532, doi:10.1016/S0022-0000(05)80063-7, MR 1279412.

- Thomason, A. G. (1978), "Hamiltonian cycles and uniquely edge colourable graphs", Advances in Graph Theory (Cambridge Combinatorial Conf., Trinity College, Cambridge, 1977), Annals of Discrete Mathematics 3, pp. 259–268, doi:10.1016/S0167-5060(08)70511-9, MR 499124.