Hamartia

The term hamartia derives from the Greek ἁμαρτία, from ἁμαρτάνειν hamartánein, which means “to miss the mark” or “to err”.[1][2] It is most often associated with Greek tragedy, although it is also used in Christian theology.[3] Hamartia as it pertains to dramatic literature was first used by Aristotle in his Poetics. In tragedy, hamartia is commonly understood to refer to the protagonist’s error or flaw that leads to a chain of plot actions culminating in a reversal from their good fortune to bad. What qualifies as the error or flaw can include an error resulting from ignorance, an error of judgement, a flaw in character, or sin. The spectrum of meanings has invited debate among critics and scholars, and different interpretations among dramatists.

Hamartia in Aristotle’s Poetics

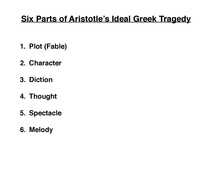

Hamartia is first described in the subject of literary criticism by Aristotle in his Poetics. The source of hamartia is at the juncture between Character and the character's actions or behaviors as outlined by Aristotle.

"Character in a play is that which reveals the moral purpose of the agents, i.e. the sort of thing they seek or avoid."[4]

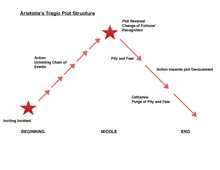

In his introduction to the S. H. Butcher translation of ″Poetics″, Francis Fergusson describes hamartia as the inner quality that initiates, in Dante's words, a ″movement of spirit″ within the protagonist to commit actions which drive the plot towards its tragic end, inspiring in the audience a build of pity and fear that leads to a purgation of those emotions, or Catharsis.[5][6]

Jules Brody, however, argues that "it is the height of irony that the idea of the tragic flaw should have had its origin in the Aristotelian notion of hamartia. Whatever this problematic word may be taken to mean, it has nothing to do with such ideas as fault, vice, guilt, moral deficiency, or the like. Hamartia is a morally neutral non-normative term, derived from the verb hamartano, meaning 'to miss the mark,' 'to fall short of an objective.' And by extension: to reach one destination rather than the intended one; to make a mistake, not in the sense of a moral failure, but in the nonjudgmental sense of taking one thing for another, taking something for its opposite. Hamartia may betoken an error of discernment due to ignorance, to the lack of an essential piece of information. Finally, hamartia may be viewed simply as an act which, for whatever reason, ends in failure rather than success."[7]

In Greek Tragedy, for a story to be ″of adequate magnitude″ it involves characters of high rank, prestige, or good fortune. If the protagonist is too worthy of esteem, or too wicked, his/her change of fortune will not evoke the ideal proportion of pity and fear necessary for catharsis. Here Aristotle describes hamartia as the quality of a tragic hero that generates that optimal balance.

"...the character between these two extremes - that of a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty." [8]

Hamartia in Christian theology

Hamartia is also used in Christian theology because of its use in the Septuagint and New Testament. The Hebrew (chatá) and its Greek equivalent (àµaρtίa/hamartia) both mean "missing the mark" or "off the mark".[9] There are four basic usages for hamartia.

- Hamartia is sometimes employed to mean acts of sin "by omission or commission in thought and feeling or in speech and actions" as in Romans 5:12, "all have sinned".[10]

- Hamartia is sometimes applied to the fall of man from original righteousness that resulted in humanity's innate propensity for sin, that is original sin.[11] For example, as in Romans 3:9, everyone is "under the power of sin".[12]

- A third application concerns the "weakness of the flesh" and the free will to resist sinful acts. "The original inclination to sin in mankind comes from the weakness of the flesh."[13]

- Hamartia is sometimes "personified".[14] For example, Romans 6:20 speaks of being enslaved to hamartia (sin).

Tragic flaw, tragic error, and divine intervention

Aristotle mentions hamartia in Poetics. He argues that is a powerful device to have a story begin with a rich and powerful hero, neither exceptionally virtuous nor villainous, who then falls into misfortune by a mistake or error (harmartia). Discussion among scholars centers mainly on the degree to which hamartia is defined as tragic flaw or tragic error.

Argument for flaw

Poetic justice describes the obligation of the dramatic poet, along with philosophers and priests, to see that their work promotes moral behavior.[15] 18th century French dramatic style honored that obligation with the use of hamartia as a vice to be punished[16][17] Phèdre, Racine's adaptation of Euripides' Hippolytus, is an example of French Neoclassical use of hamartia as a means of punishing vice.[18][19]Jean Racine says in his Preface to Phèdre, as translated by R.C. Knight:

″The failings of love are treated as real failings. The passions are offered to view only to show all the ravage they create. And vice is everywhere painted in such hues, that its hideous face may be recognized and loathed.″ [20]

The play is a tragic story about a royal family. The main characters respectives vices; rage, lust and envy lead them to their tragic downfall.[21]

Argument of birth

This tragic flaw, which is not a flaw of character primarily comes with birth as happened in the case of Achilles. When his mother dipped him river Styx to make his body strong like iron, the ankle part did not get dipped, thus that becoming his hamartia.[22]

Argument for error

In her 1963 Modern Language Review article, The Tragic Flaw: Is it a Tragic Error?, Isabel Hyde describes hamartia as both error and ″defect in character.″ As an example she mentions Hamlets hesitation and failure to act in a crucial scene. By letting the moment slip by, he failed to murder his uncle and thereby secure the throne and avenge his father.

Examples of hamartia in literature

| Play | Author | Character | Flaw | Error | Tragic Result | Misc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigone[23] | Sophocles | Antigone | excessive loyalty/stubbornness | defies Creon to bury her brother | her execution | |

| Antigone[24] | Sophocles | Creon | obstinacy/tyranny | Doesn't listen to advice or follow the laws of the gods | loses his son and wife and become a "living corpse" | |

| Hamlet[25] | William Shakespeare | Hamlet | indecisiveness; desire to avoid evil | delays justice | many deaths and madness | |

| Long Day's Journey Into Night[26] | Eugene O'Neill | James Tyrone | fiscal stinginess | hires incompetent doctor | Mary's addiction to morphine | |

| Macbeth[27] | William Shakespeare | Macbeth | excessive ambition | murders King Duncan | dishonor and death | |

| Oedipus the King[28] | Sophocles | Oedipus | hubris | kills his father, marries his mother | parricide, incest, blindness, dishonor | mistake made in ignorance of essential information |

| Phèdre[29] | Jean Racine | Phèdre | passionate love | reveals secret to nurse | dishonor and suicides | divine intervention |

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Hamartia". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. 28 September 2014.

- ↑ Hamartia: (Ancient Greek: ἁμαρτία) Error of Judgement or Tragic Flaw. ″Hamartia″. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 28 September 2014.

- ↑ Cooper, Eugene J. ″Sarx and Sin in Pauline Theology″ Laval théologique et philosophique. 29.3 (1973) 243–255. Web. Érudit. 1 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Aristotle. "Poetics". Trans. Ingram Bywater. The Project Gutenberg EBook. Oxford: Clarendon P, 2 May 2009. Web. 26 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ Fergusson 8

- ↑ The Internet Classics Archive by Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics. Web. 11 Dec. 2014. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html

- ↑ Jules Brody, "Fate, Philology, Freud," Philosophy and Literature 38.1 (April 2014): 23.

- ↑ Aristotle. "Poetics". Trans. Ingram Bywater. The Project Gutenberg EBook. Oxford: Clarendon P, 2 May 2009. Web. 26 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ http://www.blbclassic.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H2398&t=KJV, http://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?strongs=G266, and http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/miss+the+mark

- ↑ Thayer, J. H. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Harper, 1887), s.v. ?µa?t?a online at https://books.google.com/books?id=1E4VAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Thayer++Greek-English&hl=en&sa=X&ei=EsAdVdiLBM6uogSsn4LADw&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Thayer%20%20Greek-English&f=false.

- ↑ Cooper, Eugene "Sarx and Sin in Pauline Theology" in Laval théologique et philosophique. 29.3 (1973) 243-255. Web. Érudit. 1 Nov 2014 and

Thayer, J. H. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Harper, 1887), s.v. ?µa?t?a online at https://books.google.com/books?id=1E4VAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Thayer++Greek-English&hl=en&sa=X&ei=EsAdVdiLBM6uogSsn4LADw&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Thayer%20%20Greek-English&f=false. - ↑ http://biblehub.com/romans/3-9.htm

- ↑ Edward Stillingfleet, Fifty Sermons Preached upon Several Occasions (J. Heptinstall for Henry Mortlock, 1707), 525. Online at https://books.google.com/books?id=kSVWAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22weakness+of+the+flesh%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Abridged in One Volume (Eerdmans, 1985), 48.

- ↑ Burnley Jones and Nicol, 125

- ↑ Burnley Jones and Nicol,12,125

- ↑ Thomas Rymer. (2014). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/514581/Thomas-Rymer

- ↑ Worthen, B. The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama 5th ed. 444-463. Boston: Thomspon Wadsworth. 2007. Print.

- ↑ Racine, Jean. Phédre, Harvard Classics, Vol. 26, Part 3. Web. 11 Dec. 2014. http://www.bartleby.com/26/3/

- ↑ Worthen,446

- ↑ Euripedes. Hippolytus, Harvard Classics, 8.7. Web. 8 Dec. 2014. http://www.bartleby.com/8/7/

- ↑ http://ugcenglish.com/english-literature/hamartia-definition-meaning-examples/717/

- ↑ Sophocles. ″Antigone″ The Internet Classics Archive by Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/antigone.html

- ↑ Sophocles. ″Tragedy And Archaic Greek Thought" Introduction, D.L. Cairns, 2013. cf. Ant. 332-84, 582-630, 1347-53

- ↑ Worthen 282

- ↑ O'Neill, Eugene. ″Long Day's Journey Into Night,″ New Haven: Yale UP. 2002. Web 13 Dec. 2014. http://yalepress.yale.edu/yupbooks/excerpts/oneill_journey.pdf

- ↑ Shakespeare. ″Macbeth.″ The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Boston: MIT online database. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. http://shakespeare.mit.edu/macbeth/full.html

- ↑ Worthen 69

- ↑ Racine, Jean. ″Phédre,″ Harvard Classics, Vol. 26, Part 3. Web. 11 Dec. 2014. http://www.bartleby.com/26/3/

References

- Bremer, J.M. "Hamartia." Tragic Error in the Poetics of Aristotle and in Greek Tragedy. Amsterdam, Adolf M. Hakkert, 1969.

- Cairns, D. L. Tragedy and Archaic Greek Thought. Swansea, The Classical Press of Wales, 2013.

- Dawe, R D. "Some Reflections on Ate and Hamartia." Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 72 (1968): 89-123. JSTOR. St. Louis University Library, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Hyde, Isabel. "The Tragic Flaw: is It a Tragic Error?" The Modern Language Review 58.3 (1963): 321-325. JSTOR. St. Louis University Library, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Moles, J L. "Aristotle and Dido's 'Hamartia'" Greece & Rome, Second Series 31.1 (1984): 48-54. JSTOR. St. Louis University Library, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Stinton, T. C. W. "Hamartia in Aristotle and Greek Tragedy" The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Dec., 1975): 221 - 254. JSTOR. St. Louis University, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Golden, Leon, "Hamartia, Ate, and Oedipus", Classical World, Vol. 72, No. 1 (Sep., 1978), pp. 3–12.

- Hugh Lloyd-Jones, The Justice of Zeus, University of California Press, 1971, p. 212.