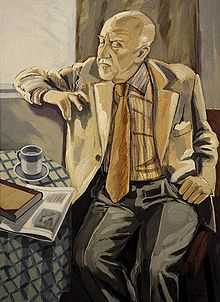

Halldór Laxness

| Halldór Laxness | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

23 April 1902 Reykjavík, Iceland |

| Died |

8 February 1998 (aged 95) Reykjavík, Iceland |

| Nationality | Icelandic |

| Notable awards |

Nobel Prize in Literature 1955 |

| Spouses |

Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir (m. 1930–40)[1] Auður Sveinsdóttir (m. 1945–98) |

Halldór Kiljan Laxness (Icelandic: [ˈhaltour ˈcʰɪljan ˈlaxsnɛs]; born Halldór Guðjónsson; 23 April 1902 – 8 February 1998) was a twentieth-century Icelandic writer. Throughout his career Laxness wrote poetry, newspaper articles, plays, travelogues, short stories, and novels. Major influences included August Strindberg, Sigmund Freud, Sinclair Lewis, Upton Sinclair, Bertolt Brecht and Ernest Hemingway.[2] He received the 1955 Nobel Prize in Literature; he is the only Icelandic Nobel laureate.

Early years

In 1905, his family (Father: Guðjón Helgason, Mother: Sigríður Halldórsdóttir) moved from Reykjavík to Laxnes in Mosfellsdalur, near the town of Mosfellsbær, about 15 km northeast of the capital. He soon started to read books and write stories. At the age of 14 his first article was published in the newspaper Morgunblaðið under the name “H.G.” His first book, the novel Barn náttúrunnar (Child of Nature), was published in 1919.[3] At the time of its publication he had already begun his travels on the European continent.[4]

1920s

In 1922, Laxness joined the Abbaye St. Maurice et St. Maur in Clervaux, Luxembourg. The monks followed the rules of Saint Benedict of Nursia. Laxness was baptized and confirmed in the Catholic Church early in 1923. Following his confirmation, he adopted the surname Laxness (in honor of the homestead where he had been raised) and added the name Kiljan (an Icelandic spelling of the Irish martyr Saint Killian).

Inside the walls of the abbey, he practiced self-study, read books, and studied French, Latin, theology and philosophy. While there, he composed the story Undir Helgahnjúk, published in 1924. Soon after his baptism, he became a member of a group which prayed for reversion of the Nordic countries back to Catholicism. Laxness wrote of his experiences in the book Vefarinn mikli frá Kasmír: “The essential feature of Vefarinn mikli is the witches' brew of ideas presented in a stylistic furioso of style.”[5] The novel, published in 1927, “... created a sensation in Iceland and was hailed by Kristján Albertsson as the epoch-making book it really was.”[6]

“Laxness's religious period did not last long; during a visit to America he became attracted to socialism.”[7] Partly under the influence of Upton Sinclair, whom he befriended in California, “... Laxness joined the socialist bandwagon... with a book Alþýðubókin (The Book of the People, 1929) of brilliant burlesque and satirical essays... one of a long series in which he discussed his many travel impressions (Russia, Western Europe, South America), unburdened himself of socialistic satire and propaganda, and wrote of the literature and the arts, essays of prime importance to an understanding of his own art...”[8] Laxness lived in the United States and attempted to write screenplays for Hollywood films between 1927 and 1929.[9]

1930s

By the 1930s he “had become the apostle of the younger generation” and was attacking “viciously” the Christian spiritualism of Einar Hjörleifsson Kvaran, an influential writer who had been considered for the Nobel Prize.[10]

“... with Salka Valka (1931–32) began the great series of sociological novels, often coloured with socialist ideas, continuing almost without a break for nearly twenty years. This was probably the most brilliant period of his career, and it is the one which produced those of his works that have become most famous. But Laxness never attached himself permanently to a particular dogma.”[11]

Laxness's next novel was Sjálfstætt fólk (Independent People, 1934, 1935) which was described as “… one of the best books of the twentieth century.” [12]

Salka Valka was published in English in 1936 and received a glowing review from the Evening Standard: “No beauty is allowed to exist as ornamentation in its own right in these pages; but the work is replete from cover to cover with the beauty of its perfection.”[13]

This was followed by Heimsljós (World Light, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1940), “… consistently regarded by many critics as his most important work.”.[14]

Laxness also traveled to the Soviet Union and wrote approvingly of the Soviet system and culture.[15]

1940s

Laxness translated Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms into Icelandic in 1941, with controversial neologisms.[16]

Laxness’ sprawling three-part historical novel Íslandsklukkan (Iceland's Bell) was published, 1943–46

In 1946 Independent People was released as a Book of the Month Club selection in the United States, selling over 450,000 copies.[17]

By 1948 he had a house built in the rural countryside outside of Mosfellsbær. He then began a new family with his second wife, Auður Sveinsdóttir, who also assumed the roles of personal secretary and business manager.

In response to the establishment of a permanent US military base in Keflavík, he wrote the satire Atómstöðin (The Atom Station), an action which, in part, may have caused his blacklisting in the United States.[18]

“The demoralization of the occupation period is described... nowhere as dramatically as in Halldór Kiljan Laxness’ Atómstöðin (1948)... [where he portrays] postwar society in Reykjavík, completely torn from its moorings by the avalanche of foreign gold”.[19]

1950s

In 1953, Laxness was awarded the Soviet-sponsored World Peace Council Literary Prize.[20]

An adaptation of his novel Salka Valka was filmed by Sven Nykvist in 1954.[21]

In 1955, Laxness was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, “for his vivid epic power which has renewed the great narrative art of Iceland”:

“His chief literary works belong to the genre... [of] narrative prose fiction. In the history of our literature Laxness is mentioned beside Snorri Sturluson, the author of the ”Njals saga“, and his place in world literature is among writers such as Cervantes, Zola, Tolstoy, and Hamsun... He is the most prolific and skillful essayist in Icelandic literature both old and new...”[11]

In the presentation address for the Nobel prize E. Wesen stated:

“He is an excellent painter of Icelandic scenery and settings. Yet this is not what he has conceived of as his chief mission. ‘Compassion is the source of the highest poetry. Compassion with Asta Sollilja on earth,’ he says in one of his best books... And a social passion underlies everything Halldór Laxness has written. His personal championship of contemporary social and political questions is always very strong, sometimes so strong that it threatens to hamper the artistic side of his work. His safeguard then is the astringent humour which enables him to see even people he dislikes in a redeeming light, and which also permits him to gaze far down into the labyrinths of the human soul.”[22]

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel prize he spoke of:

“... the moral principles she [his grandmother] instilled in me: never to harm a living creature; throughout my life, to place the poor, the humble, the meek of this world above all others; never to forget those who were slighted or neglected or who had suffered injustice, because it was they who, above all others, deserved our love and respect...”[23]

Laxness grew increasingly disenchanted with the Soviets after their military action in Hungary in 1956.[24]

In 1957, Halldór and his wife went on a world tour, stopping in: New York City, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Madison, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Peking, Bombay, Cairo and Rome.[25]

Major works in this decade were Gerpla (The Happy Warriors, 1952), Brekkukotsannáll (The Fish Can Sing, 1957), and Paradísarheimt (Paradise Reclaimed, 1960).

Later years

In the sixties Laxness was very active in the Icelandic theatre, writing and producing plays of which The Pigeon Banquet (Dúfnaveislan, 1966) was the most successful.[26]

He published the "visionary novel"[27] Kristnihald undir Jökli (Under the Glacier / Christianity at the Glacier) in 1968.

Laxness was awarded the Sonning Prize in 1969.

In 1970 Laxness published his influential ecological essay Hernaðurinn gegn landinu (The War Against the Land).[28]

He continued to write essays and memoirs throughout the 1970s and 1980s. As he grew older he began to suffer from Alzheimer's disease and eventually moved into a nursing home where he died at the age of 95.

Family and legacy

Laxness had four children: Sigríður Mária Elísabet Halldórsdóttir (Maria, b. 1923), Einar Laxness (b. 1931), Sigríður Halldórsdóttir (Sigga, b. 1951) and Guðný Halldórsdóttir (Duna, b. 1954). He was married twice: Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir (Inga, 1930-1940), and Auður Sveinsdóttir (1945-1998).[29]

His house, Gljúfrasteinn, is now a museum operated by the Icelandic government.[30]

Guðný Halldórsdóttir became a filmmaker whose first work was an adaptation of Kristnihald undir jōkli (Under the Glacier).[31] In 1999 she directed an adaptation of the Laxness story Úngfrúin góða og Húsið (The Honour of the House), which was submitted for Academy Award consideration for best foreign film.[32]

Interest in Laxness increased in the 21st century in English-speaking countries with the re-publishing of several novels and the publication of Iceland's Bell (2003) and The Great Weaver from Kashmir (2008) in new translations by Philip Roughton.[33]

A biography of Laxness by Halldór Guðmundsson, The Islander: a Biography of Halldór Laxness, won the Icelandic literary prize for best work of non-fiction in 2004.

In 2005, the Icelandic National Theatre premiered a play by Ólafur Haukur Símonarson, called Halldór í Hollywood (Halldór in Hollywood) about the author's time spent in the United States in the 1920s.

Bibliography

Works by Laxness

Novels

- 1919: Barn náttúrunnar (Child of Nature)

- 1924: Undir Helgahnúk (Under the Holy Mountain)

- 1927: Vefarinn mikli frá Kasmír (The Great Weaver from Kashmir)

- 1931: Þú vínviður hreini (O Thou Pure Vine) — Part I, Salka Valka

- 1932: Fuglinn í fjörunni (The Bird on the Beach) — Part II, Salka Valka

- 1933: Úngfrúin góða og Húsið (The Honour of the House), as part of Fótatak manna: sjö þættir

- 1934: Sjálfstætt fólk — Part I, Landnámsmaður Íslands (Icelandic Pioneers), Independent People

- 1935: Sjálfstætt fólk — Part II, Erfiðir tímar (Hard Times), Independent People

- 1937: Ljós heimsins (The Light of the World) — Part I, Heimsljós (World Light)

- 1938: Höll sumarlandsins (The Palace of the Summerland) — Part II, Heimsljós (World Light)

- 1939: Hús skáldsins (The Poet's House) — Part III, Heimsljós (World Light)

- 1940: Fegurð himinsins (The Beauty of the Skies) — Part IV, Heimsljós (World Light)

- 1943: Íslandsklukkan (Iceland's Bell) — Part I, Íslandsklukkan (Iceland's Bell)

- 1944: Hið ljósa man (The Bright Maiden) — Part II, Íslandsklukkan (Iceland's Bell)

- 1946: Eldur í Kaupinhafn (Fire in Copenhagen) – Part III, Íslandsklukkan (Iceland's Bell)

- 1948: Atómstöðin (The Atom Station)

- 1952: Gerpla (The Happy Warriors)

- 1957: Brekkukotsannáll (The Fish Can Sing)

- 1960: Paradísarheimt (Paradise Reclaimed)

- 1968: Kristnihald undir Jökli (Under the Glacier / Christianity at the Glacier)

- 1970: Innansveitarkronika (A Parish Chronicle)

- 1972: Guðsgjafaþula (A Narration of God's Gifts)

Stories

- 1923: Nokkrar sögur

- 1933: Fótatak manna

- 1935: Þórður gamli halti

- 1942: Sjö töframenn

- 1954: Þættir (collection)

- 1964: Sjöstafakverið

- 1981: Við Heygarðshornið

- 1987: Sagan af brauðinu dýra

- 1992: Jón í Brauðhúsum

- 1996: Fugl á garðstaurnum og fleiri smásögur

- 1999: Úngfrúin góða og Húsið

- 2000: Smásögur

- 2001: Kórvilla á Vestfjörðum og fleiri sögur

Plays

- 1934: Straumrof

- 1950: Snæfríður Íslandssól (from the novel Íslandsklukkan)

- 1954: Silfurtúnglið

- 1961: Strompleikurinn

- 1962: Prjónastofan Sólin

- 1966: Dúfnaveislan

- 1970: Úa (from the novel Kristnihald undir Jökli)

- 1972: Norðanstúlkan (from the novel Atómstöðin)

Poetry

- 1925: Únglíngurinn í skóginum

- 1930: Kvæðakver

Travelogues and essays

- 1925: Kaþólsk viðhorf (Catholic View)

- 1929: Alþýðubókin (The Book of the People)

- 1933: Í Austurvegi (In the Baltic)

- 1938: Gerska æfintýrið (The Russian Adventure)

Memoirs

- 1952: Heiman eg fór (subtitle: sjálfsmynd æskumanns)

- 1975: Í túninu heima, part I

- 1976: Úngur eg var, part II

- 1978: Sjömeistarasagan, part III

- 1980: Grikklandsárið, part IV

- 1987: Dagar hjá múnkum

References

- ↑ "Halldór Laxness love letters published". Iceland Review. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Halldór Guðmundsson, The Islander: a Biography of Halldór Laxness. McLehose Press/Quercus, London, translated by Philip Roughton, 2008, pp. 49, 117, 149, 238, 294

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p. 33

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p. 34

- ↑ Hallberg, Peter, Halldór Laxness. Twayne Publishers, New York, translated by Rory McTurk, 1971, pp.35, 38

- ↑ Einarsson, Stefán A History of Icelandic Literature, New York: Johns Hopkins for the American Scandinavian Foundation, 1957, p. 291 OCLC 264046441

- ↑ Halldór Laxness biography. nobelprize.org

- ↑ Einarsson, pp. 292, 316–17

- ↑ Einarsson, p. 317

- ↑ Einarsson, pp. 263–4

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Sveinn Hoskuldsson, "Scandinavica", 1972 supplement, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Jane Smiley, Independent People, Vintage International, 1997, cover

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p.229

- ↑ Magnus Magnusson, World Light, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1969, p. viii

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p.182

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p.279

- ↑ Chay Lemoine (9 February 2007) HALLDÓR LAXNESS AND THE CIA.

- ↑ Chay Lemoine (18 November 2010). The View from Here, No. 8. icenews.is

- ↑ Einarsson, p. 330

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p. 340

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p. 351

- ↑ Presentation address for the Nobel prize by E. Wesen, 1955

- ↑ acceptance speech for the Nobel prize, 1955

- ↑ Guðmundsson, p. 375

- ↑ Guðmundsson, pp. 380–384

- ↑ Modern Nordic Plays, Iceland, p. 23, Sigurður Magnússon (ed.), Twayne: New York, 1973

- ↑ Susan Sontag, p.xv, introduction to Under the Glacier, Vintage International: New York, 2005

- ↑ Reinhard Henning, Phd. paper Umwelt-engagierte Literatur aus Island und Norwegen, University of Bonn, 2014

- ↑ Guðmundsson, pp. 70, 138, 176, 335, 348, 380

- ↑ About Gljúfrasteinn – EN – Gljúfrasteinn. Gljufrasteinn.is. Retrieved on 29 July 2012

- ↑ Under the Glacier (1989) . imdb.com

- ↑ The Honour of the House (1999). imdb.com

- ↑ The man who brought Iceland in from the cold – Los Angeles Times. Latimes.com (23 November 2008). Retrieved on 29 July 2012

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Halldór Laxness |

- Gljúfrasteinn, the Halldór Laxness Museum website

- Nobel Prize website

- Petri Liukkonen's biography

- Dennis Haarsager's biography

- Laxness in Translation (English translations reviewed)

| ||||||

| ||||||

|